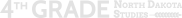

Figure 3. These early garden tools were used by the Mandan and Hidatsa to tend their crops and gardens. Left to right: a rake made of antlers, a hoe made from a scapula (shoulder bone) of an animal, a willow rake, and a sharpened stick used as a seed drill. (SHSND 0075-0386)

North Dakota’s first farmers, the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Indians, raised their crops on the bottomland of the Missouri and Knife Rivers. Bottomland is low-lying land along a river. Bottomland soil is moist and not as hard-packed as land farther away from a river. Bottomland soil is also fertile,Rich in materials needed for plants to grow which means it is rich in materials needed for plants to grow.

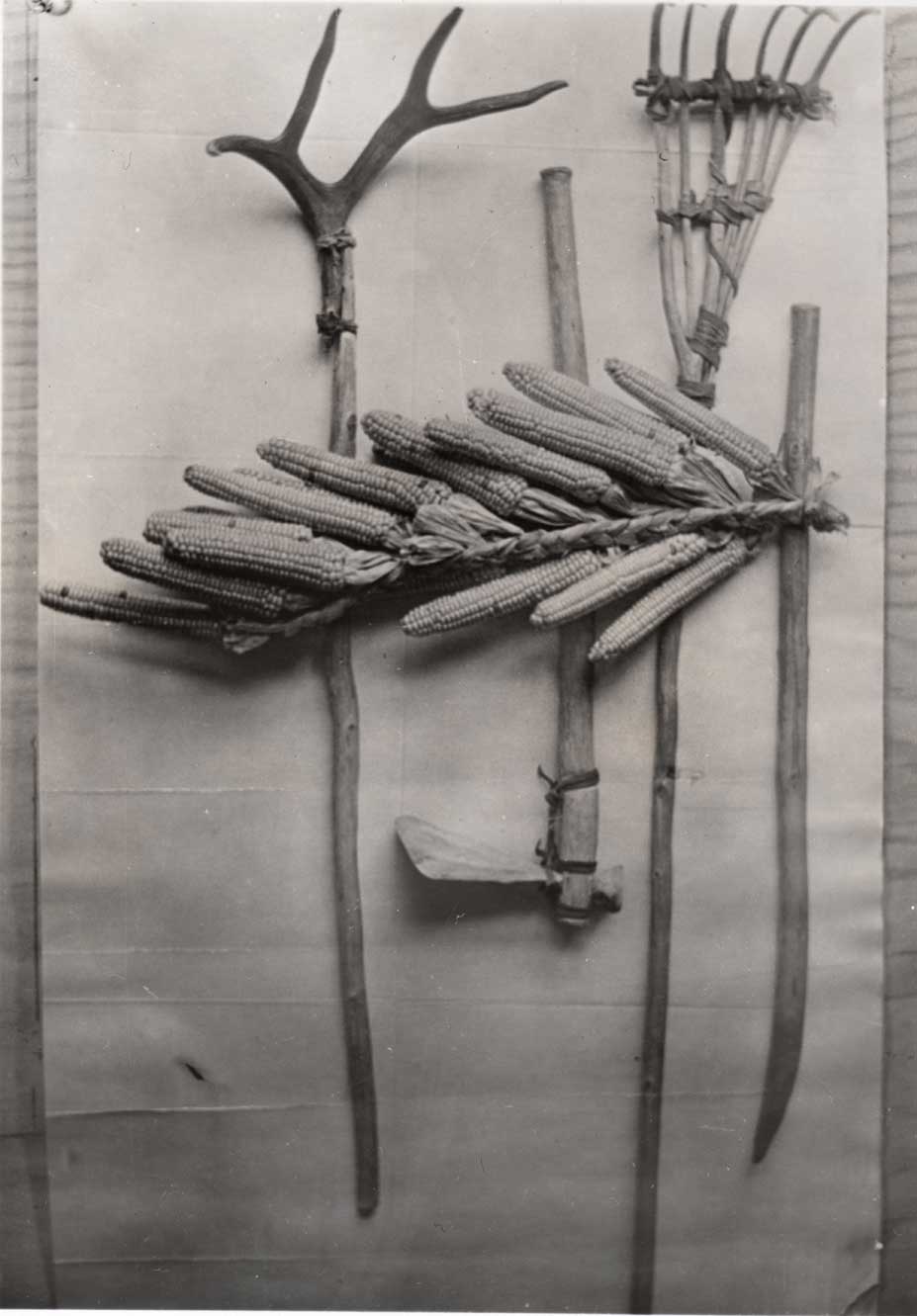

Figure 4. Corn was a main crop grown by the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara along the Missouri and Knife Rivers. (USDA)

Figure 5. Scattered Corn, a Mandan woman, is shown with her garden hoe. (SHSND D0566-1)

Figure 6. Growing and harvesting squash was important to the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara people. (oldyellowhorsegifts.com)

Figure 7. This woman is shown hoeing her garden with a handmade bone hoe, 1914. (SHSND 0086-0283)

Women owned the farm land and did most of the farming. The main crops were corn, beans, sunflowers, and squash. They developed many different varieties of these crops. Some varieties of corn were better for eating fresh, others made popcorn. Some varieties of corn were better when dried and put in storage for winter.

Several steps were necessary to prepare the fields for cultivation. In the fall of the year, trees, shrubs, brush, and grass were cut down and left to dry over the winter. In the spring, this dry material was burned. The burning helped loosen the soil. Also, burned vegetationPlant Life added nutrients to the soil. NutrientsMaterials that make the soil fertile are materials that make the soil fertile.

Following the burning, women broke up the ground with wooden digging sticks. They also used hoes and rakes made from sticks and antlers, or bones. When they began to raise crops, the women did not have metal tools and made all their garden tools themselves. After 1800, when Euro-Americans• Americans with European ancestors

• Sometimes called “whites” (also called “whites”) began trading with the tribes, women farmers got metal tools through trade.

Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara farmers did not have calendars. They looked for natural signs to tell them when it was time to plant. For example, when the wild gooseberry plant got its leaves, the farmers knew it was time to plant the corn.

They also developed many varieties of each crop species. According to Buffalo Bird Woman, a Hidatsa farmer, nine different varieties of corn and five different kinds of beans were raised in the Hidatsa fields.

When the snow was gone and the ground was thawed and warm, usually around the middle of April, women planted sunflowers. Using the tools and their hands, women scooped the dirt into many little hills around the edges of the field and placed three sunflower seeds in each hill. The sunflowers grew tall and formed a colorful fence around each woman’s garden before it was time to harvest the seeds.

Corn was the major crop of the agricultural tribes and occupied the most space in each garden plot. In early May, farmers formed little hills of dirt, three to four feet apart. Hidatsa women planted six to eight corn kernels per hill. Sahnish women planted five kernels per hill. Sometimes another crop of corn was planted later in summer.

Women planted the squash after the corn. This planting took place in late May or early June. Farmers germinated squash seeds before planting them. This means that they had been placed in a container where they could be moistened (made somewhat wet) and had started to grow. When the seed germinated, a sprout grew from one end. When the sprout was one inch long, the seed was planted in little hills about 15 inches across (diameter).

After the squash seeds were planted, the women farmers sowed or planted beans. Beans were planted near the corn so that the bean stalks could climb up the corn stalks. The corn stalks supported the beans and the beans shaded the ground around the corn to keep it cool and weed-free.

The Hidatsas, Mandans, and Sahnish raised other crops including pumpkins, gourds, melons, and tobacco.

As soon as all the seeds had been planted, the women began hoeing weeds out of the gardens. They went to the garden plots early in the morning and worked until the day became too hot to work in the sun. Then they returned to their earthlodges to complete their other household work. If the day cooled, they might return to the garden.

The work time in the fields was also a social time for the women. They visited with other women and often sang as they worked. Young men would sometimes hang around the fields and try to catch the attention of the young women.

As the crops grew and began to mature (mah-CHUR), or reach full development, the women had to protect the gardens from animals that might damage the crops. Blackbirds, crows, ground squirrels, raccoons, horses, and other animals found their favorite foods growing in the gardens. Sometimes, boys would sneak into the gardens to take fresh corn to roast.

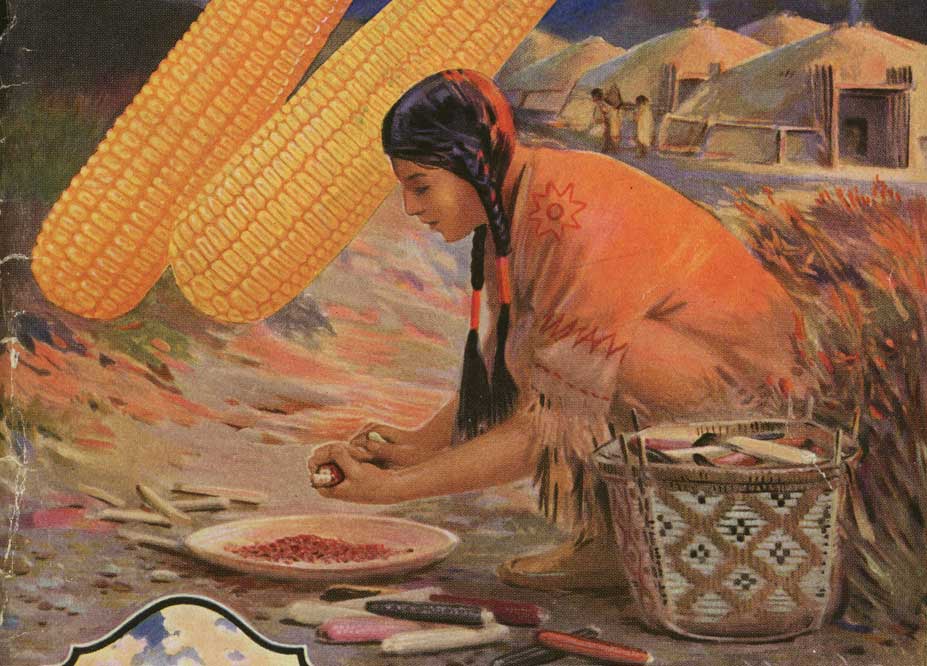

Figure 8. Corn grown by early American Indians needed to be shelled and stored for winter use. (SHSND 10190)

The women had various methods of protecting their fields. One technique was to create a scarecrow. Two sticks were stuck into the ground for legs, and two other sticks were tied on as outstretched arms. The head was made of a piece of bison skin shaped into a ball. An old buffalo robe was draped over the frame, and a belt was tied around its waist.

The birds were frightened away because the scarecrow looked like a man. After a few days, however, the birds saw that the figure never moved. They then lost their fear and returned to the field.

A more effective way of protecting the fields was to use a “watcher’s stage.” A watcher’s stage was a high platform on which girls or women would sit and sing together as they watched the fields and chased away intruders. The square platform was accessed by a ladder and was large enough for two to four girls.

When a girl was 10 to 12 years of age, she was given the responsibility of being a “watcher.” The watchers would climb onto the stage around sunrise and would guard the fields until the sun went down in the evening. Some continued this custom even after they had grown up and were married.

Each year, the “watching” season began in early August when the ears of corn started to form. It continued until all of the corn had been harvested.

Harvesting began in late July or early August. HarvestingGathering mature crops from the fields means gathering mature crops from the fields. The first crop ready for harvest was squash, followed by corn and beans. Sunflowers took longer to mature than the other crops, so even though sunflowers were planted first, they ended up being the last harvested. Harvesting was usually finished by the end of October.

Women prepared their harvested crops for storage by setting them out to dry. Women used bone knives to slice squashes into rings. They placed the rings on a stick and hung the stick in the sunlight where the rings dried. Corn, beans, and sunflowers dried on the stalk before harvest. Women and girls removed these seeds after they were very dry. Some seeds were set aside for planting the next year. The rest of the dried corn kernels, beans, sunflowers, and squash rings were placed in an underground storage space called a cache (kash) pit. The cache pit kept the food supply safe until it was time to use it.