Farmers were required to cultivate part of the land they received under the Homestead Act. In order to do this, they first had to “break the sod.” SodGrass-covered soil that is held together by matted roots is grass-covered soil that is held together by matted roots.

A team of horses or an ox pulled a breaking plow which turned over the sod. A breaking plow• Implement with a heavy, curved blade to turn over sod

• Pulled by a horse or an ox was an implement that had a heavy, curved blade, which dug into the sod and turned it over.

Figure 21. Four teams of horses plowing sod on the Anders Hultstrand farm near Fairdale, North Dakota. (Hultstrand Collection, Institute for Regional Studies, NDSU, 2028.147)

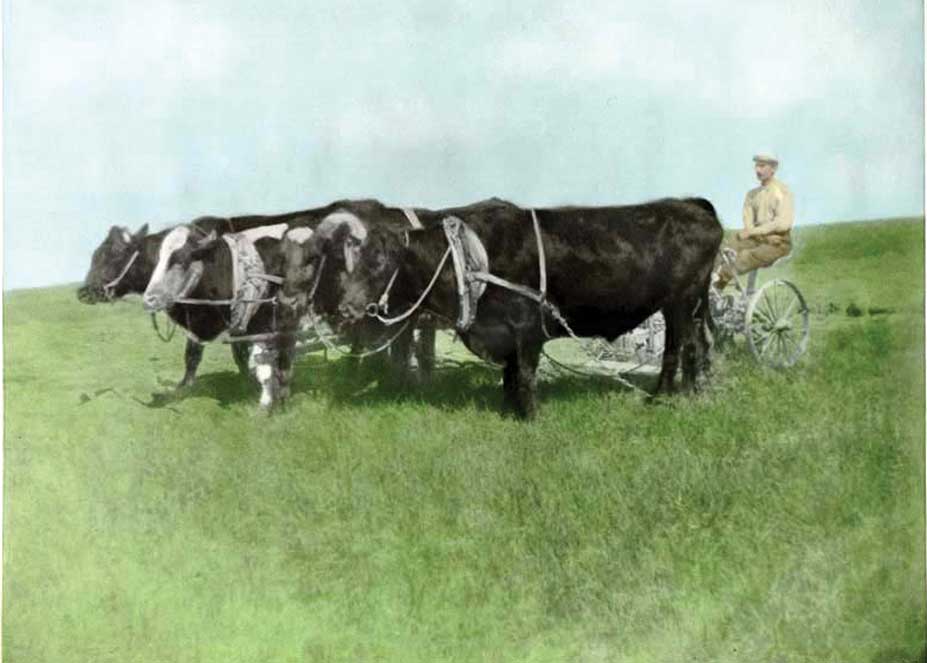

Figure 22. A team of oxen pulls a plow in Divide County, North Dakota, 1906. (Hultstrand Collection, Institute for Regional Studies, NDSU, Fargo, 2028.177)

A person walking behind the plow used handles to control the direction and depth of the plow blade. This person sometimes draped the horses’ reins loosely around his or her neck. If the horses were hard to control, another person might walk along to drive the horses.

Breaking sod was hard work. The farmer walked up to 20 miles a day as he or she worked to keep the plow blade at a uniform (the same) depth and plow in a straight line. Some women homesteaders broke their own sod, while others hired a neighbor to do it for them.

Homesteaders depended heavily on their horses and cattle. Horses were the first choice of North Dakota pioneer farmers for doing field work. Oxen were used by some farmers because they were cheaper than horses. An ox• A full-grown bull that has been neutered

• Huge animal, stronger than a horse is a full-grown bull that has been neutered. (“Oxen” is the plural of “ox.”) Oxen are strong, but they move slowly and are sometimes stubborn.

Mules had been used on bonanza farms, but they were not generally used by North Dakota homesteaders for two reasons. A mule• Offspring of a male donkey and a female horse

• Not able to reproduce themselves is the offspring of a male donkey and a female horse, and they are unable to reproduce themselves. Also, mules cost more than horses.

Milk cows provided dairy products for the family, and even some people in towns kept milk cows. Chickens supplied eggs and meat. The women of the family generally took care of milking the cows and taking care of the chickens. Some farmers also raised sheep, pigs, and other livestock.

It was important to keep the farm animals in good health by providing adequate water, feed, and shelter for them. A permanent barn was often constructed before a permanent house was built.

The major grains raised by the pioneers were wheat, oats, corn, and flax. Most of the wheat was shipped off to mills to be made into flour. The oats and corn were usually used as feed for horses and other livestock.

Flax generally brought a good price at market where the oil was pressed out of the seeds and made into linseed oil. This oil was used in making paint, printer’s ink, wood polish, and other products. The stalks of the flax plant could be used for making linen, a type of material used for clothing, tablecloths, and other items.

Figure 23. A scythe was used to cut grain as shown in this illustration. (Library of Congress)

During the earliest years of homesteading, or in cases where the homesteader did not have money to buy implements, most of the work had to be done by hand. If a homesteader did not have a breaking plow, he or she could borrow one or exchange work with a neighbor who had one. At first, many people planted seeds by hand and harvested by cutting the grain with a scythe• Long, curved blade with a handle

• Early tool used for cutting grain (syth), a long, curved blade with a handle.

As time went on, farmers obtained more implements and machinery. Besides a breaking plow, some of the other horse-drawn implements included a harrow, a drill, a binder, a mower, a rake, and a homemade stoneboat.

A stoneboat• A type of sled that could glide over fields, grass, snow, or ice

• Pulled by a team of horses did not have wheels and was not driven on the road. It was actually a type of sled consisting of a pair of log runners covered with boards. Stoneboats were used for hauling stones out of the fields, but they were also used for hauling many kinds of items on the farm. A stoneboat was pulled by a team of horses, and the driver stood on the platform. This device could glide over fields, grass, snow, or ice.

Except for the breaking plow and the stoneboat, most implements had a metal seat where the driver sat. Drivers handled the horses and also used levers to control the operation of the machine.

The breaking plow turned the sod over, but the clods of earth needed to be broken up and evened out before the crops could be planted. This was done with a harrow,• Implement with sharp teeth that digs into the soil

• Breaks up clods of earth an implement with sharp teeth that dug into the soil. If the implement had sharp, circular plates instead of teeth, it was called a disk.Harrow with sharp, circular plates instead of teeth

A drillImplement that plants crop seeds was an implement that planted the crop seeds. Rows of small tubes made tiny furrows, dropped in the seeds, and covered up the furrows. A furrowA long, narrow groove cut in the ground is a long, narrow groove cut in the ground.

Figure 26. Cutting and binding grain on a farm near Adams, North Dakota, about 1900. (Hultstrand Collection, Institute for Regional Studies, NDSU, 2028.145)

Figure 27. A farm family works together shocking a field of oats, Hettinger County, North Dakota, early 1900s. (SHSND 0090-0104)

Figure 28. A threshing crew poses for a photograph near Park River, North Dakota, early 1900s. (Hultstrand Collection, Institute for Regional Studies, NDSU, 2028.309)

After the crops had grown all summer, they had to be harvested. The first step

in harvesting was cutting down the grain. Binders were used for this purpose. A binderMachine that cut grain, gathered it into bundles, and tied the bundles with twine (BINE-der) was a machine that cut the grain, gathered it into bundles, and tied each bundle with a piece of twine. A binder was pulled by a team of horses or mules and had a seat for the driver.

After the grain was cut and bundled, it was shocked. ShockingPicking up bundles of grain from the ground by hand and placing them upright in groups to dry involved picking up the bundles from the ground and placing them upright in groups of about a dozen to dry. Bundles of wheat were heavy, but oats were quite a bit lighter. Children who were not yet strong enough to shock wheat could help shock the oats.

The final step in harvesting the grain was threshingSeparating the grain from the straw This was the busiest time of year on the farm. Someone in the neighborhood who owned a threshing machine would hire a crew of men and go from farm to farm to thresh. Often the threshing crew was made up of family and neighbors. The crew might be made up of from 10 to 30 men. Each farm’s threshing usually took from two to four days if the weather was good.

The threshing machine,• Separated the kernels of grain from the stalks

• Operated by a crew of workers run by a steam engine, was set up in the field and operated by several workers. Most of the crew hauled bundles. Using pitchforks, the men loaded bundles from the shocks into hayracks (special wagons for hauling hay or bundles of grain). When a hayrack was filled, it was driven to the threshing machine, and the bundles were pitched into the machine.

The threshing machine separated the kernels of grain from the stalks. The grain kernels were discharged into wagons, and the straw (stalks) was spit out into a straw pile beside the machine. Some of the straw was used for winter bedding for the horses and cattle, but the rest of the straw piles were usually burned in the spring.

Work at threshing time was generally divided by gender. The men and older boys worked on the threshing crew, while the women and girls had the responsibility of cooking for the hungry workers.

Five meals a day were served. Breakfast in the morning, dinner at noon, and supper in the evening were generally eaten in the farmhouse, while morning and afternoon lunches were brought to the men in the field.

The women got up before dawn to begin baking bread and preparing breakfast. Eggs, meat, potatoes, pancakes or bread usually were the main items served for breakfast. After breakfast was served and the dishes were washed, baking and cooking for the next meal was begun immediately.

Morning lunch, which was served at about 9:00 was made up of cold meat or egg sandwiches, donuts, cookies, and beverages. The afternoon lunch, served at about 3:30 or 4:00, was made up of about the same items as the morning lunch. Horses got a short rest during the lunch times.

The threshing crew came to the farmhouse at noon to eat dinner and give the horses a longer rest. Before eating, the men washed up in wash basins set up outside. The main course for dinner usually consisted of meat, potatoes, several vegetables, and bread. Pie or cake, as well as donuts and cookies, were served for dessert.

Threshing usually stopped for the day at about 7:30 p.m., and the men came back to the farmhouse for supper. The supper menu was similar to that of the dinner.

Even the youngest girls and boys had their responsibilities. They helped set the table, run errands, and do other chores. Sometimes girls and boys were responsible for carrying the lunches out to the field and taking drinking water to the work crews.

Figure 29. A threshing crew awaits a hot meal served from the nearby cook car, 1915. (F.A. Pazandak Collection, Institute for Regional Studies, NDSU, 2026.112)

A few threshing crews brought along a cook car with women who were hired to follow the crews from one farm to another. A cook car looked like a small house on wheels. It contained a curtained-off sleeping area for the women, a stove, and a work space. The use of cook cars was common in the days of bonanza farming.

Flax and corn were harvested differently from wheat and oats. Flax was bundled and dried out, and the flax was put through a de-seeding machine. The ears of corn were picked by hand, and the husks were pulled off. Corn stalks were either mowed down or plowed under to act as fertilizer for the soil. The corn needed to dry, so the ears were placed in a “corn crib,” which was a structure with openings on the sides for airflow. When it had dried enough, each ear was inserted into a hand-cranked corn sheller, which scraped the kernels off the cob. The corn was stored as livestock feed, and corncobs were used as fuel for stoves in some pioneer homes.

Figure 30. Men stack hay with the help of horses, early 1900s. (SHSND 0075-0697)

Even though some oats and corn were used as livestock feed, the cheapest and most available feed for horses and cattle was hay. HayGrass that has been cut and dried to be used as livestock feed is grass that has been cut and dried to be used as livestock (farm animal) feed. The grass was cut with a horse-drawn mower, which had a sickle (moving blades) on one side.

After it had dried for a few days, the hay was raked together with a hay rake. As a team of horses pulled the rake, the tines, or prongs, of the rake gathered the hay. The driver then pulled a trip cord which dropped the bunch of hay that had been gathered. These bunches were later pitched into a hay rack, and the hay was hauled to the barn to be stored for the winter. If the barn did not have enough room for all of the hay, the rest was stacked outside in “haystacks.”