On October 14, 1804, the Corps of Discovery crossed into what is now North Dakota. The men set up camp about five miles south of present-day Fort Yates. From the time they had left St. Louis, Missouri five months earlier, they had traveled over 1,200 miles up the Missouri River.

As the keelboat and the two pirogues continued to work their way upriver, they went past the remains of On-A-Slant, a Mandan village which had been abandoned after the smallpox epidemic of 1781. The people who survived this epidemic had moved north to be closer to the Hidatsa people who had also lost a large number of their population in the epidemic.

Just south of present-day Bismarck, Lewis and Clark saw their first grizzly bear. In Lewis’s journal, he commented on the beautiful scenery in that part of the country but also noted, “The leaves are fast falling.” Winter was coming soon. The first snowfall of the season came on October 21.

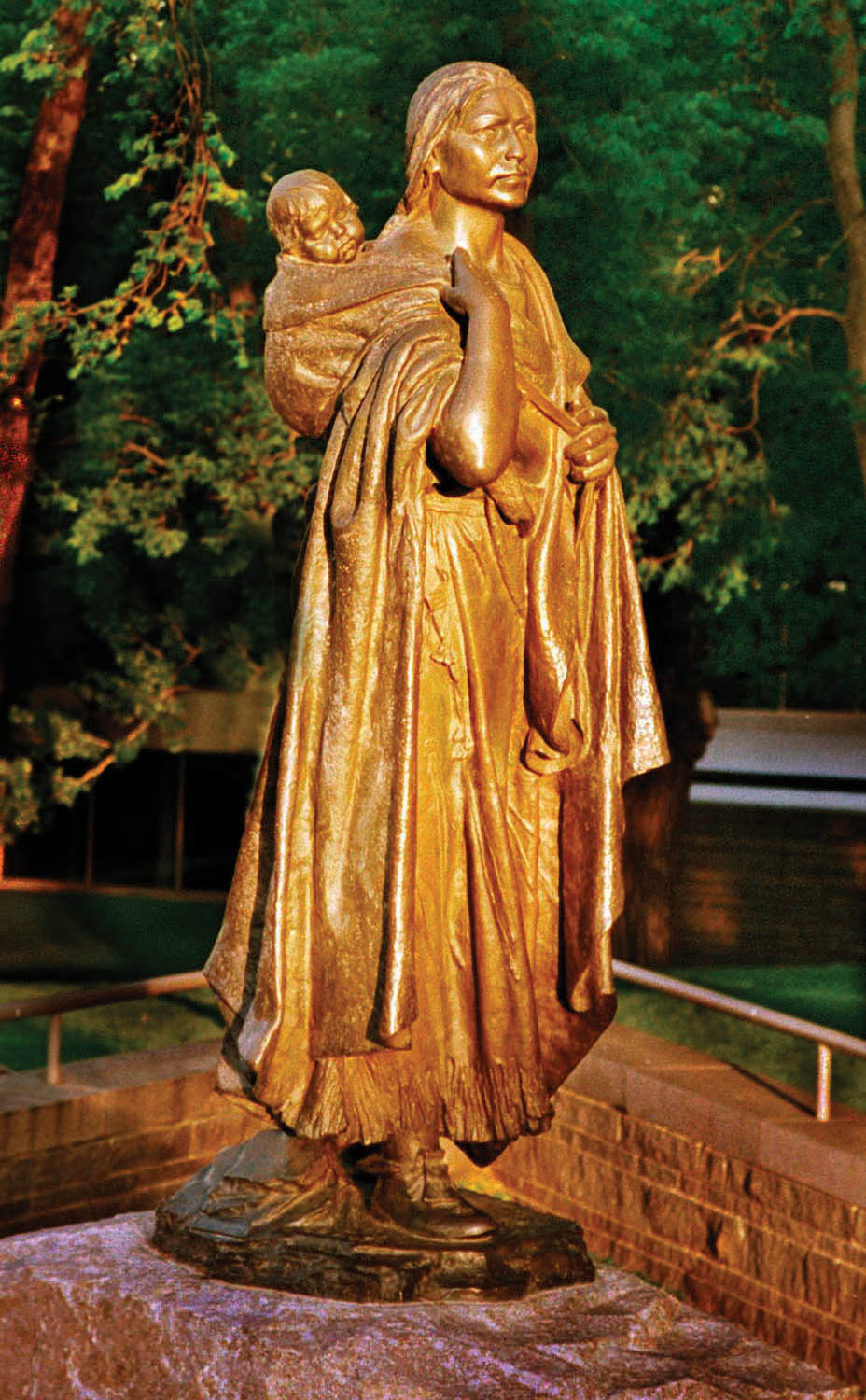

Figure 40. Lewis and Clark entering a Mandan Village. (SHSND 11549)

Toward the end of October, the expedition reached the Mandan and Hidatsa earthlodge villages near the present-day cities of Washburn and Stanton, North Dakota. The Mandan people lived along the Missouri River, and the Hidatsa people lived nearby along the Knife River. The people of the earthlodge villages raised crops and engaged in trade. They welcomed all peaceful visitors.

Altogether, the population of these villages was many times larger than the population of St. Louis. The villages had been a busy trading center for many years. British, French, and Canadian trappers and traders, as well as dozens of other Indian tribes, carried on a bustling trade business with the Mandan and Hidatsa Indians.

Lewis and Clark wanted to open the great Mandan and Hidatsa trade center to American traders. They found the Mandan and Hidatsa people to be friendly and helpful, so they decided to spend the winter in the area. They picked a location near the Mandan and Hidatsa villages about seven miles below the mouth of the Knife River. This site is about 12 miles from the present-day city of Washburn, North Dakota.

On November 4, the men began to cut down cottonwood trees to use in building their winter home. The work went slowly because the large, heavy cottonwood timbers had to be carried to the building site. The fort was three-sided with two rows of cabins placed at an angle and an 18-foot-high stockade around the perimeter. Lewis and Clark named this winter home "Fort Mandan."• Winter home of the Lewis and Clark Expedition in 1804–05

• Located near present-day Washburn

Figure 41. Fort Mandan. A reconstructed Fort Mandan is located near present-day Washburn, North Dakota. (Lewis and Clark Fort Mandan Foundation)

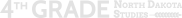

Figure 42. This statue of Sakakawea is located on the state capitol grounds in Bismarck, North Dakota. (SHSND 2003-09-06-08)

Fort Mandan was completed on December 24, and on Christmas Day 1804, the American flag was raised. This was the first time the nation’s flag had ever been displayed over what is now North Dakota.

A French-Canadian trader who was married to a Mandan woman was hired by the captains as an interpreter for the Mandan language. Since nobody in the expedition could speak or understand the Mandan or Hidatsa languages, Lewis and Clark needed someone to help them communicate. The trader and his wife moved into the fort.

A few days later, another French-Canadian by the name of Toussaint Charbonneau• Husband of Sakakawea

• A French-Canadian hired as a Hidatsa interpreter (too-Saunt Shar-ben-oe) came to the fort and asked to be hired as a Hidatsa interpreter. He had lived in a Hidatsa village for many years. His young wife, Sakakawea, was expecting a child.

Sakakawea• Wife of Toussaint Charbonneau who was hired by the expedition as a Hidatsa interpreter

• Traveled with the Lewis and Clark Expedition to the Pacific Ocean and back, carrying her baby

• Helped the expedition succeed

• One of the most famous women in the history of the United States

• Largest lake in North Dakota is named after her had been born into the Shoshone tribe in Idaho but was captured by Hidatsa warriors when she was 11 years old. She was brought to a Hidatsa village, and later Charbonneau took her as his wife.

The captains hired Charbonneau as a Hidatsa interpreter. Sakakawea was to be an important part of the expedition, too, because she could speak the language of the Shoshone.

On New Year’s Day, 1805, some of the men from the expedition celebrated at the Mandan villages. Pierre Cruzatte, who was blind in one eye, brought a fiddle and played lively music for dancing. He also entertained the crowd by dancing on his hands.

Figure 43. York talking with members of the expedition, including Captain Lewis. This photo shows a reenactment portraying York. (U.S. Army at www.army.mil)

Figure 44. Private John Shields was a blacksmith on the Lewis and Clark Expedition. This photo shows a reenactment portraying John Shields. (U.S. Army at www.army.mil)

The Mandan people called William Clark “Chief Redhead” because of his red hair. The person they were the most interested in, however, was Clark’s servant, York.Only African-American (Black) member of the Corps of DiscoveryThey had never before seen an African-American, or Black person, and some of them rubbed his skin to see if the color would rub off. He was a very strong man who enjoyed showing off his great strength. He also joked around by saying that he ate little children.

The winter of 1804-05 was very harsh, with the temperature falling as low as 45 degrees below zero. The earthlodge homes of the Mandan and Hidatsa people were warm and cozy, but the Fort Mandan cabins were not well insulated. The only fuel available for heating the cabins was wood from the cottonwood trees that had to be cut into pieces for the fireplaces. Some of the men were kept busy at this task. Many of the men suffered from frostbite, a condition that happens when a person’s skin freezes.

One of the most valuable members of the expedition was John Shields, the blacksmith. A blacksmithA person who makes and shapes things out of iron is a person who makes and shapes things out of iron. To shape iron, it is heated to very high temperatures over a forge,Small open furnace used by a blacksmith to heat iron so it can be shaped or small open furnace, and hammered into shape. John Shields used North Dakota lignite coal to heat his forge. He made metal items. Lewis and Clark traded these metal items to the Mandan and Hidatsa people for corn, meat, and other foods. The members of the expedition survived the very cold winter with the help of the Indians and the food they got in trade.

Figure 45. A dug‐out canoe on display at the Lewis and Clark Interpretive Center in Washburn, North Dakota. (Lewis and Clark Fort Mandan Foundation)

On February 11, 1805, Sakakawea gave birth to a baby boy. He was named Jean Baptiste Charbonneau,• Sakakawea and Toussaint Charbonneau’s baby

• Nicknamed “Pomp” but Lewis and Clark called him “Pomp.”• Nickname of Sakakawea and Toussaint Charbonneau’s baby

• Real name was Jean Baptiste When his parents joined the expedition, Pomp went with them. His mother carried him on her back to the Pacific Ocean and back. A woman carrying a baby was a significant symbol of peace when the Corps met Indian tribes along the way.

Throughout the winter, the men hunted, repaired equipment, and made other preparations for the next part of their journey. They also cut cottonwood trees which they used to carve six dug-out canoes to use on their continuing journey.

While living near the Mandan and Hidatsa villages, the men of the Corps of Discovery decided to adopt the footwear of North Dakota Indians. Moccasins were far more comfortable and practical than the boots the men had worn from St. Louis to Fort Mandan. For the remainder of the journey, all of the members of the expedition wore moccasins.

Lewis and Clark spent a lot of time visiting with the people in the earthlodge villages and learning important information about the other tribes they would meet along the way. The captains gathered all the information that they could about the unknown areas they were about to explore. They used their navigational instruments to map their exact location. They planned the next stage of their journey using the information the Mandan and Hidatsa people shared with them. Some of the Hidatsa people had been as far west as the Rocky Mountains, but they always traveled by horseback and had never crossed the mountains.

In October, when the Corps of Discovery had arrived at their winter camp, they had left the keelboat in the water. When the cold weather set in, the river froze so thick that herds of bison could walk across it. Of course, the keelboat was trapped in the ice for the winter. Some of the men spent time trying to hack it out, but that was an impossible task. They could have saved themselves the work because the problem solved itself in the spring.

Toward the end of March, geese were flying north over Fort Mandan, and on March 25, the ice on the river started to break up. After five months in the company of the Mandan and Hidatsa people, some of the men of the expedition began loading the keelboat for its trip back to St. Louis.

The keelboat cargo included furs to be sold and also items that were to be delivered to President Jefferson. Among these were bison robes; bows and arrows; samples of different kinds of plants; animal skins, bones, and antlers; and stuffed birds and animals. A few live animals and birds were put in cages to send to President Jefferson. All of these plants and animals had never been seen east of the Mississippi River. The captains also sent written reports and maps they had made.

On Sunday afternoon, April 7, 1805, the keelboat with 12 men headed downstream toward St. Louis. That same afternoon, the Corps of Discovery set out in the opposite direction to continue on with “The Greatest Adventure in American History.”

Figure 46. These 12‐foot‐tall steel statues of Meriwether Lewis, William Clark, and Mandan Chief Sheheke greet visitors to the Fort Mandan Interpretive Center in Washburn, North Dakota. (Lewis and Clark Fort Mandan Foundation)

Figure 47. Seaman Overlook. This is a statue of Seaman, the loyal companion of Meriwether Lewis. It is located near the Lewis and Clark Interpretive Center at Washburn, North Dakota. (Lewis and Clark Fort Mandan Foundation)

Thirty-three people, including Charbonneau, Sakakawea, and Pomp, left Fort Mandan to go upstream on the Missouri River. In their visits with the Mandan and Hidatsa people, Lewis and Clark had learned that they would need to get horses from the Shoshone tribe in order to cross the mountains. Women were not usually allowed to go on expeditions, but the captains decided to let Sakakawea come along with her husband so that she could translate the Shoshone language. It was a wise decision.

As the two pirogues and six new dug-out canoes pulled away, Lewis walked along the shore. He often walked, rather than riding in a canoe, and sometimes trudged as far as 30 miles in a day. He did not walk alone, however; his faithful, furry friend, Seaman, was never far from his side.

SeamanNewfoundland dog that belonged to Meriwether Lewis was a Newfoundland dog that weighed about 120 pounds. A Newfoundland is a very strong dog that enjoys water and swims well. Lewis had purchased Seaman for $20 before the journey began. In those days, $20 was a very high price to pay for a dog. Lewis wrote about Seaman several times in his journal. One night near present-day Williston, Lewis had been worried because the dog stayed out all night. Lewis was afraid that he was lost for good, but the next morning before 8:00 a.m., Seaman returned to camp.

Even though Seaman belonged to Lewis, the other members of the expedition were fond of him also and called him “Our Dog.” He was more than a pet, however. At night, if bears or bison got too close to the campsite, Seaman would bark furiously and chase them away.

Seaman loved to chase any animal that moved. He also liked to retrieve birds and animals that had been shot and were in the water. Once when he went after a wounded beaver, it bit him in the leg and cut a blood vessel. Lewis and Clark worked together to get the bleeding stopped. They saved Seaman’s life.

Lewis wrote in his journal that the Indians were impressed by Seaman. Seaman was much larger than the dogs that lived in Indian villages. Indians liked to watch him chase animals and play. Lewis noted that the Indians thought Seaman was a very intelligent dog.

Figure 48. North Dakota’s prairie dogs were described as “barking squirrels” by Lewis and Clark. (ND Game and Fish Department)

Lewis and Clark were amazed by the abundance of wildlife, some of which they had never seen before. The great herds of bison sometimes stretched as far as the eye could see. Packs of gray wolves usually followed the herds of bison. Other game animals such as antelope, elk, and deer were also plentiful. The most valuable animal for the fur-trade business was the beaver which was found everywhere along the river.

The explorers were very interested in prairie dogs. They had not seen prairie dogs before, so they called them “barking squirrels.” Millions of these mammals lived on the prairie where they burrowed their homes underground. It is now known that the “barking squirrels” written about by Lewis and Clark were really prairie dogs.

On April 25, the Corps of Discovery reached the confluence of the Yellowstone River and the Missouri River near the present-day city of Williston, North Dakota. Clark noted in his journal that this would be a good place for a fort. Almost a quarter of a century (25 years) later, the fur-trading post, Fort Union, was built on that site.