Norwegians made up the largest group of immigrants who settled in North Dakota. German-Russians were the second-largest group of immigrants. The German-Russian immigrants were not Russians at all. They were actually Germans whose ancestors had moved to Russia from Germany about a hundred years before. German-Russians• A German whose ancestors lived in Russia for about 100 years

• Germans from Russia are also called “Germans from Russia.”

Catherine II (the second), also called Catherine the Great, became the empress (ruler) of Russia in 1762. She wanted to improve the economy, or make more money for the country, by bringing in colonies of settlers to farm the land.

Figure 59. German-Russian immigrants, McIntosh County, North Dakota. (SHSND 0075-233)

Figure 60. Catherine II of Russia, also known as "Catherine the Great."

In order to persuade people to settle in Russia, Catherine II made several promises. The new people could set up their own communities and have special rights that Russians did not have. They would be given free land; they could keep their own language and customs; they could have their own local governments; they could set up their own schools and churches; and they would not have to serve in the Russian military.

This offer sounded exciting to many people in Germany who saw it as an opportunity to make better lives for themselves. Thousands of German families moved to southern Russia, where fertile land was waiting to be farmed. They established their own communities and did not socialize with their Russian neighbors. Their lifestyles were preserved, and they lived just as they had in Germany.

For the next hundred years, the Russian rulers continued honoring the promises made by Catherine the Great. Then Alexander II came to power and decided that the Germans would no longer have special privileges. He took away their local governments and required that the Russian language be taught in their schools. He also proclaimed that the men would have to serve in the Russian army.

The German colonists did not want to lose their identity. They wanted to get away from Russia so that they could keep their own language, customs, and traditions. They did not want their young men to be drafted into the Russian military. Visitors and land agents from the other side of the Atlantic Ocean brought stories about free or cheap land and new opportunities. The Germans in Russia were interested. This new land of promise was the United States of America.

Germans from Russia who immigrated to North Dakota received help from some of the Germans who were already in the area. One of these men was John Wishek. He did so much for the German-Russian immigrants in the south-central part of the state that they called him “Father Wishek.”

John Wishek helped the German-Russians select land, file land claims, and find jobs. Wishek and his partners were responsible for bringing ten thousand people to McIntosh, Logan, and Emmons counties. Wishek established several townsites, including the one that carries his name.

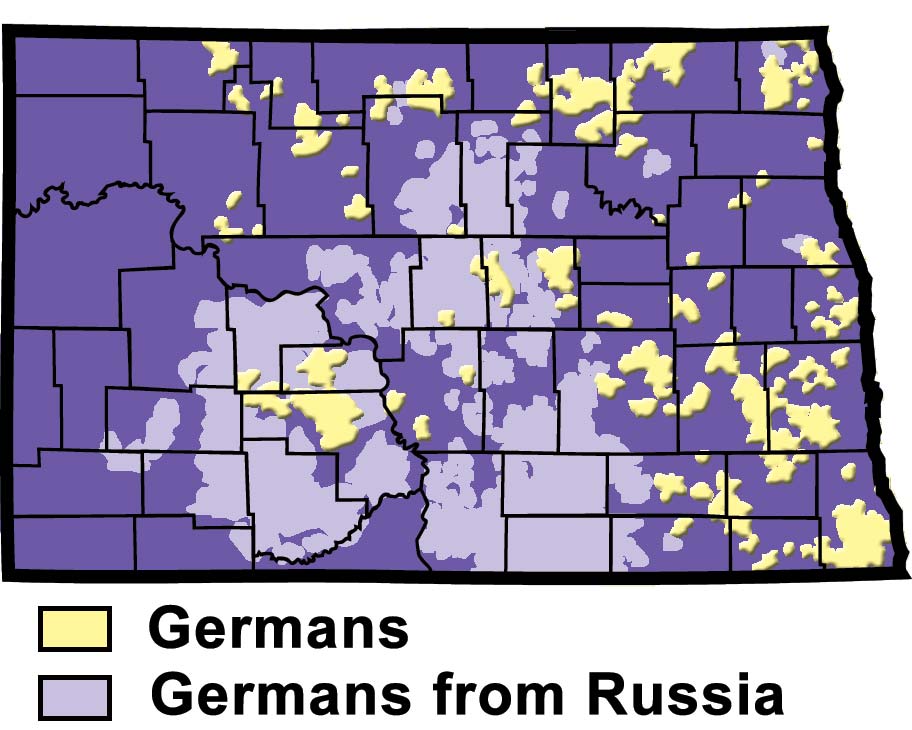

German-Russian settlements were mainly concentrated in three areas of the state—the north central, the south central, and a portion of the southwest. This concentration of Germans from Russia has been called the “German-Russian Triangle.”

The German-Russians were noted for their strong work ethic. This means they valued work, and they worked hard. Many of the German-Russians felt that working at making a living was more important than getting an education, and most thought that high school and college were unnecessary.

Figure 61. Settlement of Germans and Germans from Russia in North Dakota. (SHSND-ND Studies, Data by William Sherman)

Even though schooling may not have been important to some of the German-Russians, they expected their children to behave when they did go to school. Children were told that if they were punished in school, they would get punished again when they got home.

When the Germans and German-Russians came into contact with each other in North Dakota, they usually did not have much to do with each other. The Germans from Russia had kept their customs, traditions, and language the same as those of their ancestors who had moved to Russia a century before. Germany, on the other hand, had become more modern, and their culture and language had changed somewhat. The Germans sometimes had a hard time understanding the speech of the German-Russians, who spoke what the Germans called “low German.”

German-Russians were proud of their traditions and did not want to be absorbed into American culture. They kept their tight-knit communities and continued to speak the German language for many years.