When the Dawes Act was passed in 1887, it included the possibility of full United States citizenship for those Indians who were successful in farming or ranching on their allotments, and had met some of the government’s assumptions about “civilization.” In the 19th century, people thought a civilized person wore clothing made of cloth – suits for men, dresses for women. Civilized people sent their children to school, spoke English, and attended a Christian church. Some or all of these qualities were used by federal Indian agents to determine which allotted Indians were prepared for citizenship. American Indians who had these qualities were considered “competent” to become citizens.

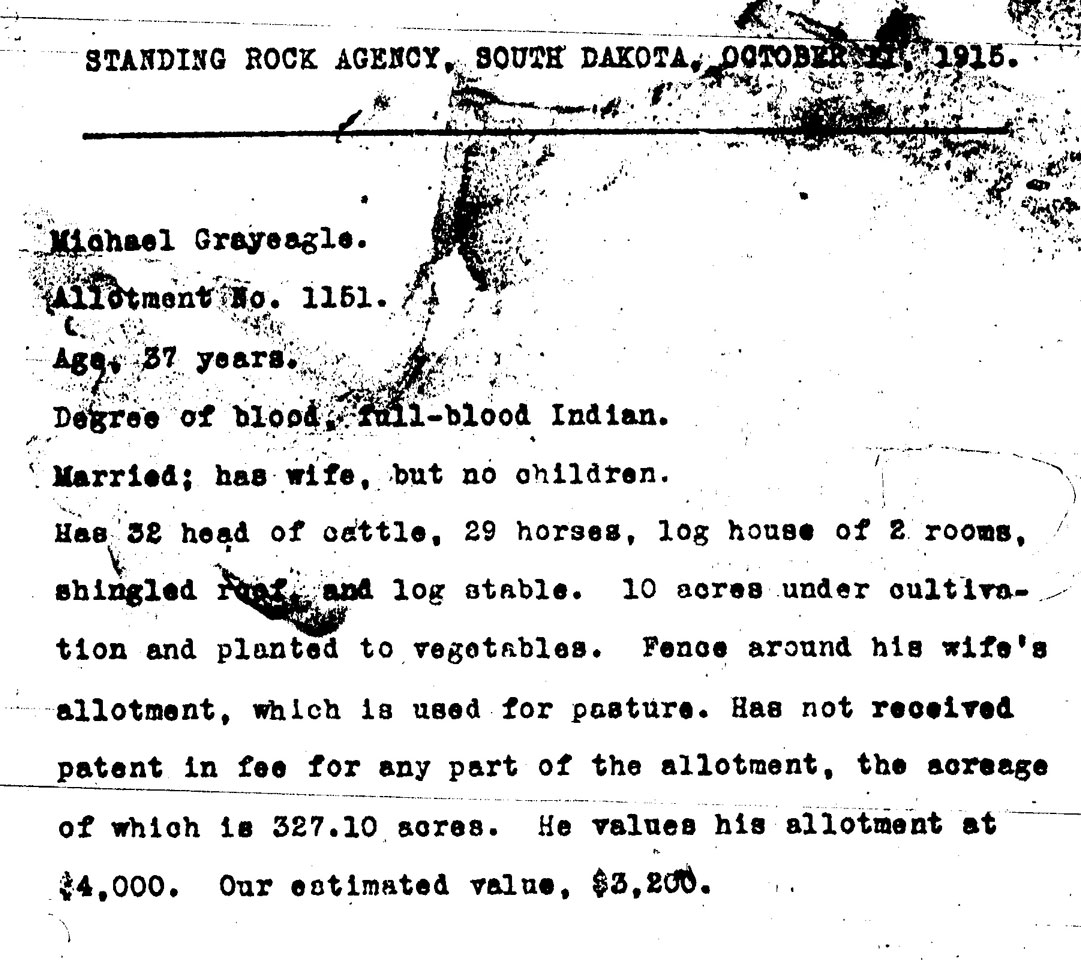

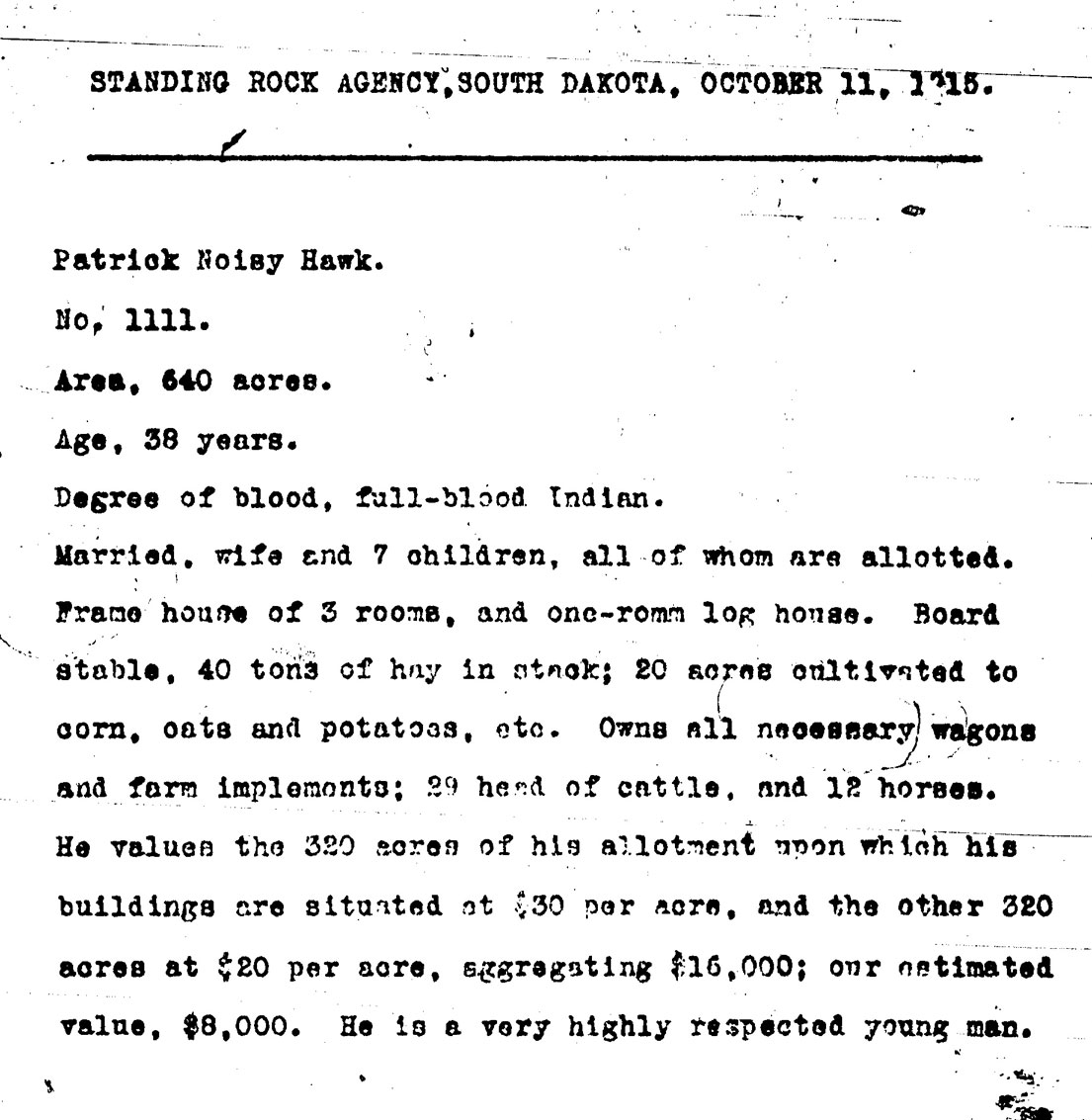

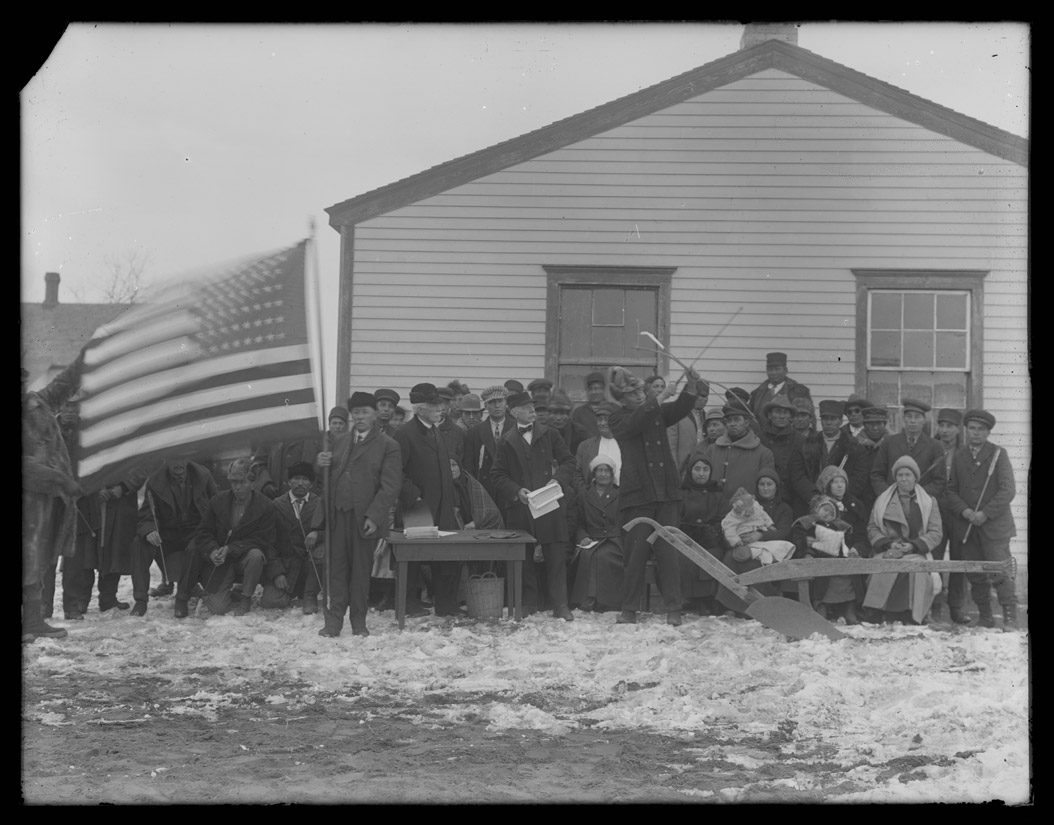

On the Standing Rock Reservation, the first allottees (those who had received an allotment) received patents to their allotted lands after 1910. Receiving the patent meant that the allottee qualified for U. S. citizenship. In 1915, Secretary of the Interior Franklin Lane and Major James McLaughlin corresponded about a ceremony to celebrate citizenship. McLaughlin was a former Standing Rock agent and, in 1915, a traveling inspector for the Commissioner on Indian Affairs. The ceremony Lane and McLaughlin created was an elaborate celebration of citizenship and cultural transition for the allottees.

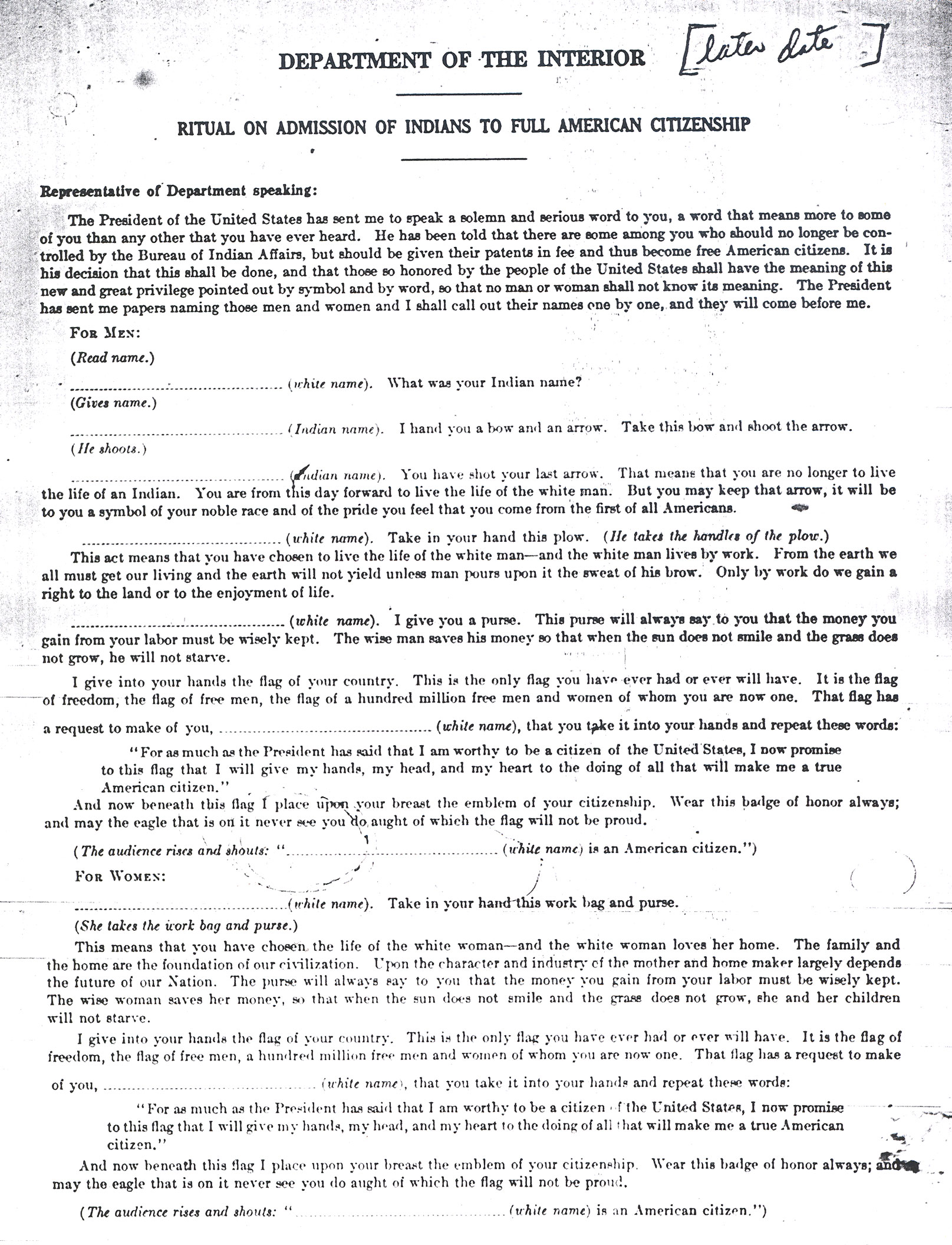

McLaughlin and Lane discussed what symbols might be used to demonstrate the transition. They considered using a coup (mistakenly written as “coos”) stick because it indicated bravery. But as Major McLaughlin pointed out, the coup stick and the tradition of counting coup on an enemy was only practiced by Plains Indians. The citizenship ceremony was to be applied at reservations all over the United States. They thought that the most universal symbol would be the bow and arrow which were used at some time by nearly every tribe. (See Image 11)

The ceremony asked the new citizen to shoot the arrow for the last time and to take the plow as a new symbol of U.S. citizenship. (See Document 19) The plow represented independent citizenship. Thomas Jefferson had tried to steer the U.S. economy in the direction of agriculture, because he believed that farmers were politically and economically independent. Personal independence was thought to be necessary in a democracy. American Indian men were connected symbolically to the American ideal of independent citizenship through the plow. In addition, men were given a wallet (“purse”) to symbolize their new role as workers who earn money. Though the United States had moved in the direction of industry throughout the 19th century, the small farmer remained an important national symbol. Many Indian tribes were settled on land that could not support farming. Still, Indians were expected to raise crops. Successful farming was part of what was expected of American Indians who wanted to become citizens. (See Image 12)

Women of the tribe also received allotments and became citizens in their own right. Their symbols were different. The purse and work bag (a bag for keeping knitting or sewing projects) symbolized their role as mother and homemaker. (See Image 13)

Each new citizen also received a badge of citizenship and a U. S. flag. Major McLaughlin designed the badge. (See Document 20) Each new citizen was expected to wear the badge as a daily reminder of the rights and responsibilities of citizenship. (See Document 21)

Why is this important? Under United States law, anyone born in one of the states or a territory is considered a “natural” citizen. This law did not apply to American Indians (until 1924) because of the special status of Indian tribes as “domestic, dependent nations.” The ability to acquire citizenship status meant acquiring the rights of a citizen as well as the duties of a citizen. The rights included owning property, protection of the law, and voting. The duties included paying taxes on private property, obeying the law, and voting.

The citizenship ceremony at Standing Rock recognized a major change in the relationship of the Lakotas and Yanktonais to the federal and state governments. Before allotment, the federal government dealt with the tribe. After allotment, individual citizens also had a relationship with governments. However, the Indian agent on the reservation made the final decision. If an agent did not declare an individual to be “competent,” that person did not qualify for citizenship.