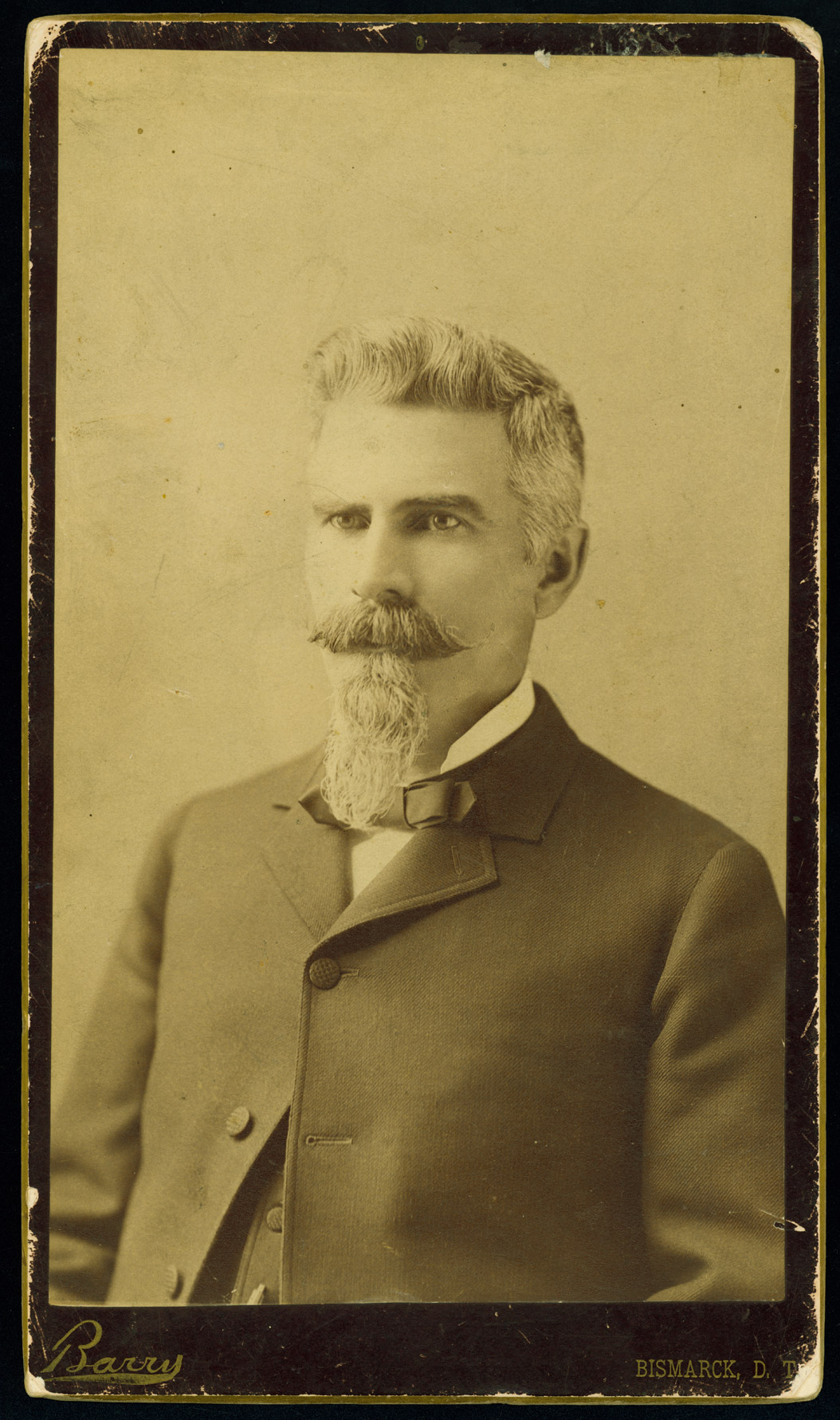

In March 1908, the supervising agent at Standing Rock Reservation called a council between Standing Rock tribal members and Inspector James McLaughlin of the U. S. Indian Commission (See Image 10). McLaughlin wanted to present information on two Congressional bills that concerned the opening of the Standing Rock Reservation to settlement (See Document 16).

Major McLaughlin was the U. S. Indian agent at Standing Rock from 1881 to 1895. He was well-acquainted with the men who met in council. He explained that there were two bills in Congress and that there would have to be a compromise between the bills. McLaughlin asked the Lakotas and Yanktonais of Standing Rock to consider his (McLaughlin’s) suggested compromise or to make their own offer. McLaughlin knew that Washington officials had already decided to take land from the tribes.

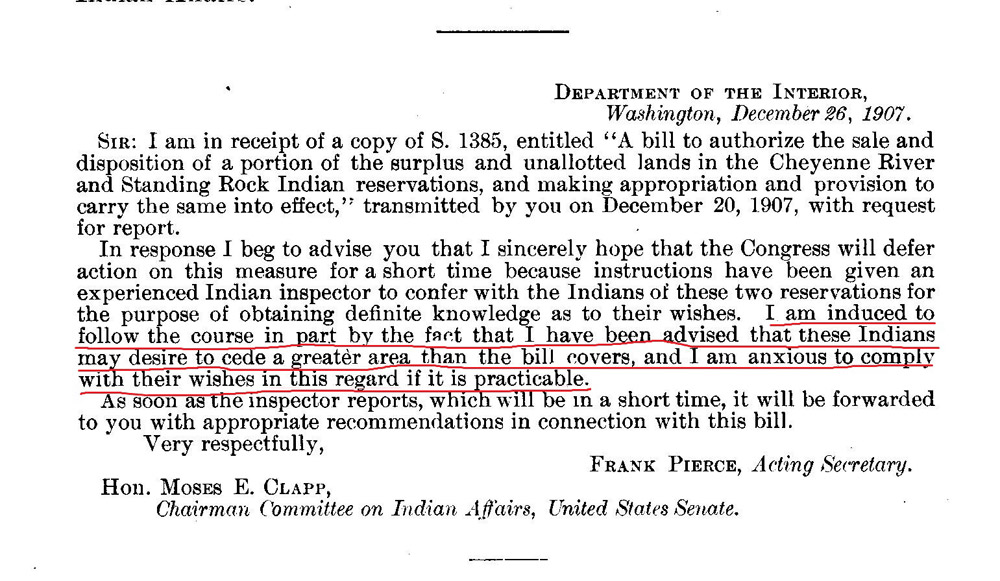

Congress did not have to confer with the Lakotas and Yanktonais of Standing Rock to open the reservation to settlement. However, Franklin Pierce, acting Secretary of the Interior, had suggested to Senator Clapp that the residents of Standing Rock might be willing to give up even more land than was included in the original bill (See Document 17).

At the council, McLaughlin explained the power of Congress over Indian tribes. That power came from an important United States Supreme Court case. The case, known as Lone Wolf vs Hitchcock, was decided in 1903. Lone Wolf, on behalf of the Kiowa tribe of which he was a member, sued to stop allotment on the Kiowa-Commanche-Apache reservation in Oklahoma. The justices of the Supreme Court heard the case. They decided that the powers of Congress were superior to the terms of the treaties that had been signed years earlier. This decision meant that if Congress decided to make a change to any reservation, it had the power to do so. Even though this decision was made in the case of the Kiowas, it applied to all reservations.

McLaughlin suggested that the Lakotas and Yanktonais of Standing Rock allow Congress to open much of the western portion of the reservation in both North and South Dakota. He also told the council that if they did not agree, Congress might take more land.

The council met and decided to give up 29 townships (668,160 acres). This was about one-half of what Congress wanted. However, it is evident that members of the council disagreed with one another. No one was anxious to give up any land, but some members of the council thought that they would be better off to follow McLaughlin’s recommendation.

Congressional Representative Gamble of South Dakota and Representative Marshall of North Dakota had presented different versions of the bill to the House of Representatives. They had felt a lot of pressure from people in their states who wanted to acquire land on the reservation. Representative Gamble wrote a report on the bill on April 1, 1908. In his report, he stated that

The Indians [of Standing Rock] are satisfied to have the surplus and unallotted lands disposed of under the provisions of the bill as amended. The area as described in the bill . . . provided for the opening of a strip of land 18 miles in width running east and west through the entire width of the reservation and in addition a strip of land on the western part of the reservation 35 miles wide by 100 miles in length. The total acreage embraced therein and provided to be opened is 2,972,160 acres. Of this amount, . . . 1,244,160 acres is in the Standing Rock Reservation. The lands provided to be opened under the provisions for the bill are all within the State of South Dakota, except 365,600 acres in the State of North Dakota.

. . . The lands reserved for the use of the Indians [about 1,250,000 acres] . . . are ample and more than sufficient for the present and future needs of the Indians of the respective tribes.

Congress passed the bill on May 29, 1908. Commissioner of Indian Affairs, F. E. Leupp, noted that the new bill recognized the council’s demand that the school lands (sections 16 and 36 of each township) should be purchased by the U. S. Government for $2.50 per acre. However, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs rejected the tribal council’s request that the government make annual payments to the tribe from the land sales. The U. S. Treasury would continue to hold the payments received from land sales. The government paid directly to the tribe only the 3% interest earned on the income from the sale.

The three-person committee with the responsibility to set a price on the land consisted of a “resident citizen of the States of North or South Dakota, one representative of the Indian Bureau and one person holding tribal relations with one of said tribes of Indians.” It is likely that Congress intended that the “person holding tribal relations” be a member and resident of the Standing Rock reservation, but the meaning of that phrase was not entirely clear.

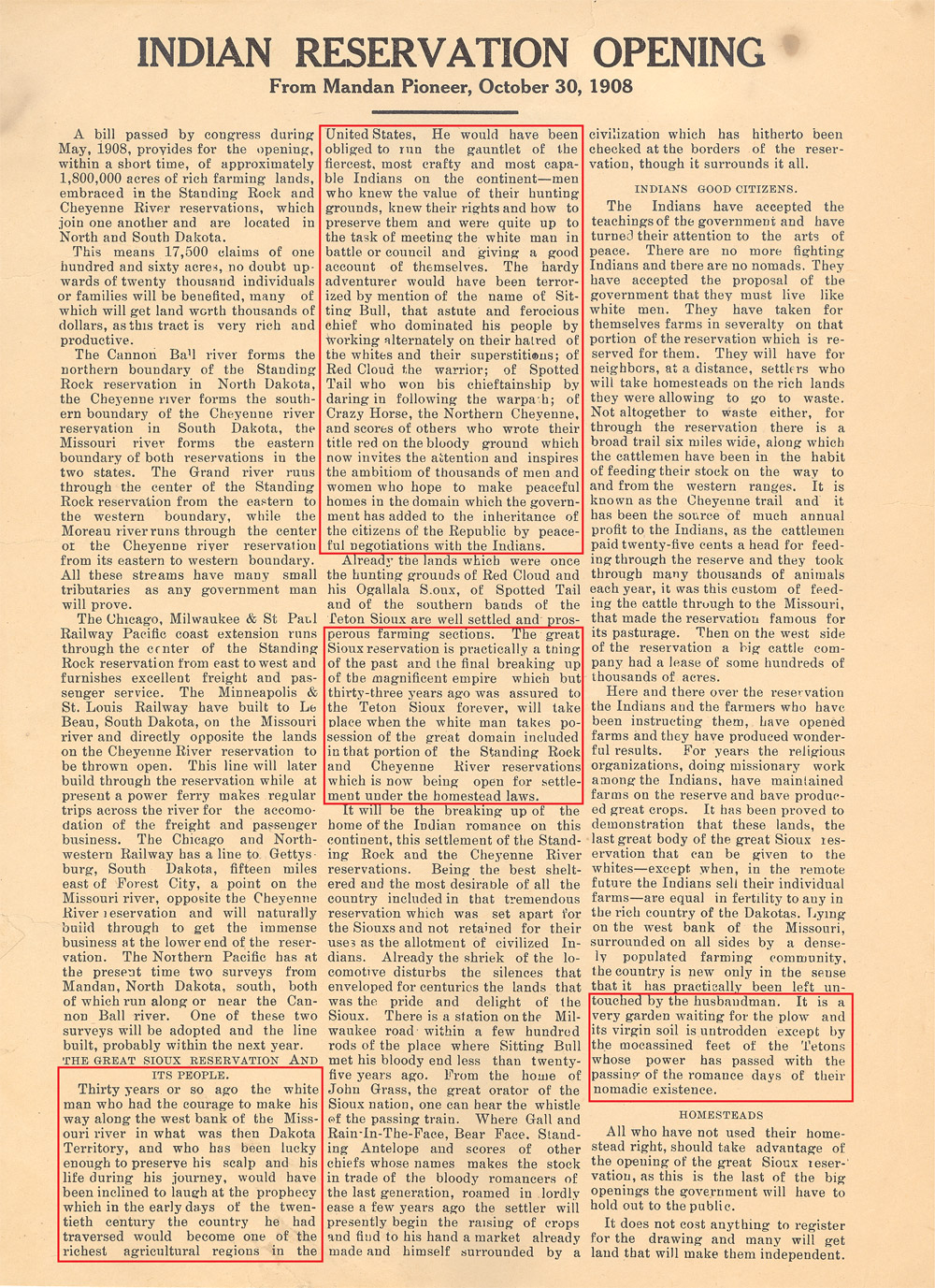

In 1910, the Standing Rock and Cheyenne River (South Dakota) reservations were opened for settlement.

Why is this important? Reading about the progress of this bill tells us a lot about how Congress worked with Indian tribes. The tribe accepted that unallotted reservation lands would be opened to non-Indian settlers, but wanted to do so on their own terms. However, Standing Rock leaders had little reason to think that members of Congress would accept their terms. What Congress, the Department of the Interior, and the Commissioner of Indian Affairs thought of as negotiating for approval of the law, the residents of Standing Rock saw as one more attack on the treaties they signed in 1851 and 1868. As a result of this process, the tribes of Standing Rock lost control over much of their reservation lands.

Sources: Sale of Portion of Surplus Lands on Cheyenne River and Standing Rock Reservations Apil 1, 1908 (Calendar No. 474. Senate Report No. 439. 60th Congress, parts 1 and 2. SHSND).