The history of the Turtle Mountain Chippewa Reservation is very different from the histories of the other reservations in North Dakota. The Turtle Mountain Chippewas did not participate in the Treaty of Fort Laramie. The first treaty to define their territory was the Sweet Corn Treaty of 1858. (See Document 27)

The Chippewas had been in conflict with the Dakotas over hunting territory for many years before 1858. However, in 1858, the two tribes met in council to renew an earlier agreement about territory. With assistance from United States negotiators, the two tribes agreed to the Sweet Corn Treaty which divided the territory between them. According to the Sweet Corn Treaty, Chippewa territory began in northwestern Minnesota, included much of the Red River Valley north of present-day Fargo, and continued west to the Missouri River. The Chippewa lands included about 11,000,000 acres. The Dakotas and Chippewas agreed to respect each other’s territory while allowing hunting on the other’s land if necessary. The Sweet Corn Treaty was respected as a historic foundation for land claims in the years after 1858.

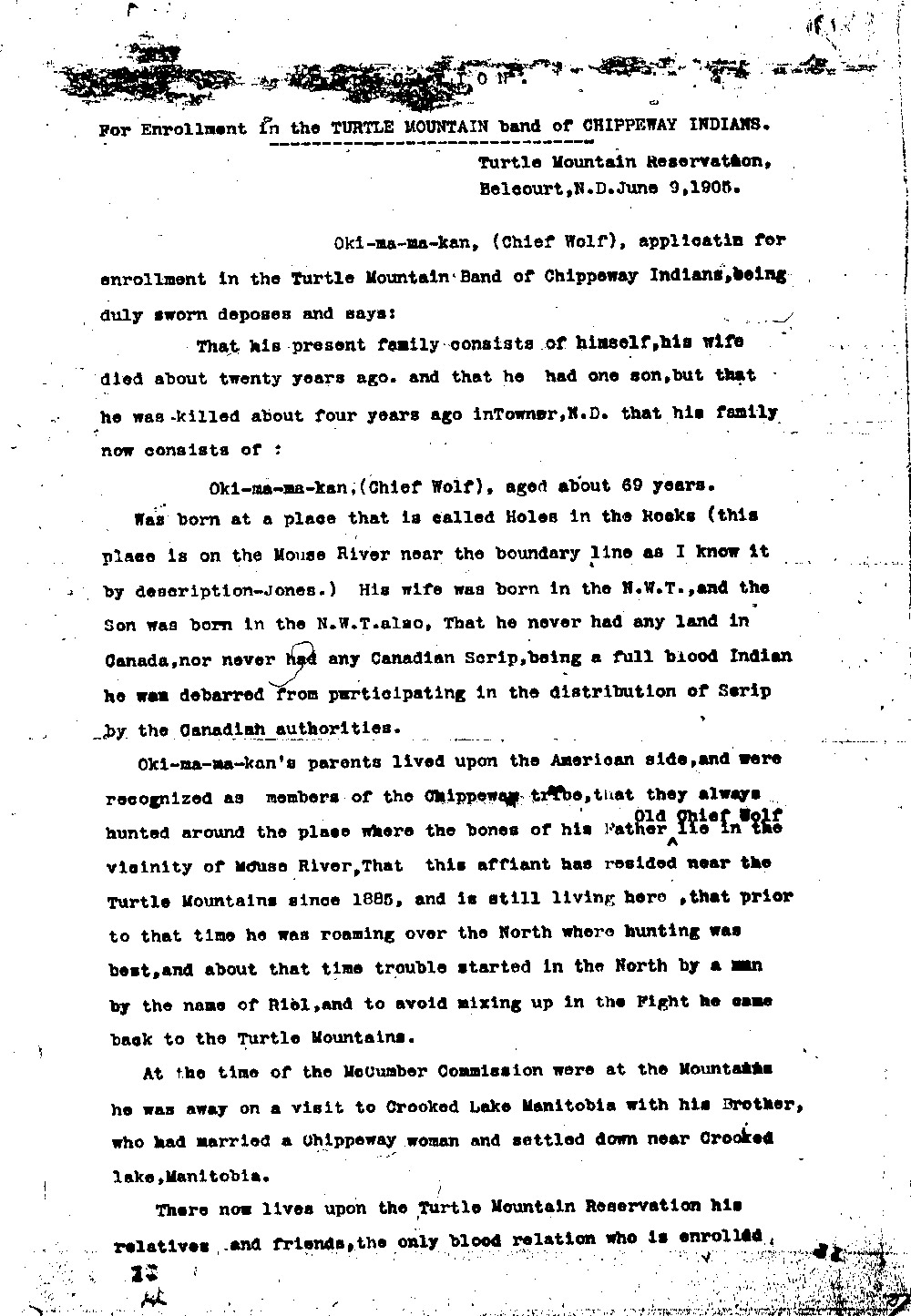

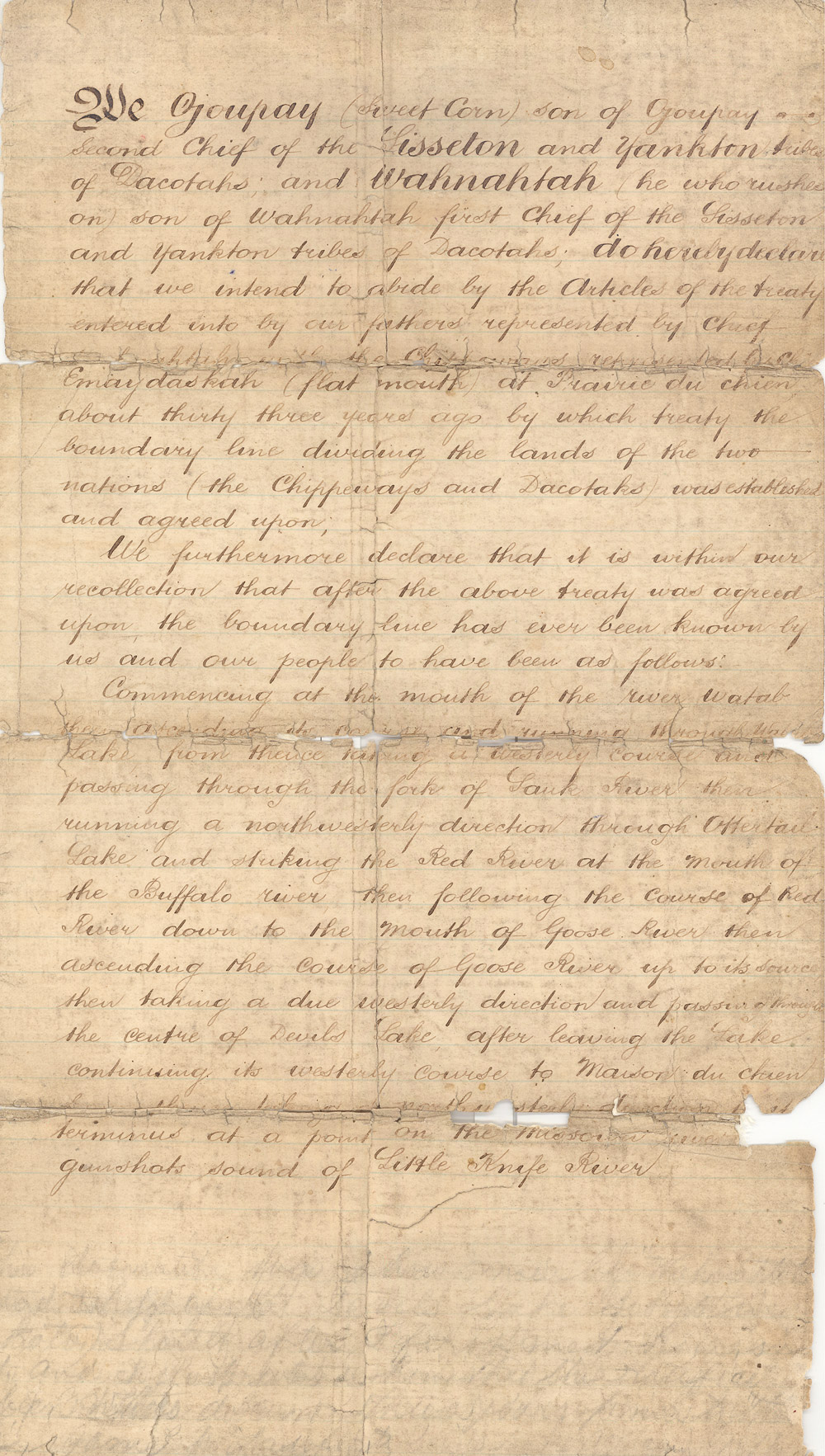

Document 27 Transcription

Document 27. The agreement between the Chippewas and the Dakotas was written down on behalf of the Dakotas by an English speaking agent of the U.S. government in 1858. The clerk used the older spellings of Dacotah and Chippeways. The names of some of the rivers have changed, but other locations in present-day North Dakota have not changed at all. Maison du Chien is now called Dog Den Butte (Butte Township in northwestern McLean County.) However, it is difficult today to know exactly how far the sound of a gunshot traveled in 1858. The Chippewas used this treaty to identify the extent of their traditional lands when dealing with the federal government on land cessions in the 1890s.

We Ojoupay (Sweet Corn) son of Ojoupay second chief of the Sissseton and Yankton tribes of Dacotahs; and Wahnahtah (he who rushes on) son of Wahnahtah first chief of the Sisseton and Yankton tribes of Dacotahs; do hereby declare that we intend to abide by the Articles of the treaty entered into by our fathers represented by Chief Emay das kah (flat mouth) at Priaire du Chien about thirty three years ago by which treaty the boundary line dividing the lands of the two nations (the Chippeways and Dacotahs) was established and agreed upon.

We furthermore declare that it is within our recollection that after the above treaty was agreed upon the boundary line has ever been known by us and our people to have been as follows:

Commencing at the mouth of the river Wahtab, thence ascending its course and running through Lake Wahtab: from thence taking a westerly course and passing through the fork of the Sauk River: thence running in a northerly direction through Otter Tail Lake and striking the Red River at the mouth of Buffalo River: thence following the course of the Red River down to the mouth of Goose River: thence ascending the course of Goose River up to its source: after leaving the Lake, continuing its western course to Maison du Chien: from thence taking a northwesterly direction to its terminus at a point on the Missouri River within gunshot sound of Little Knife River.

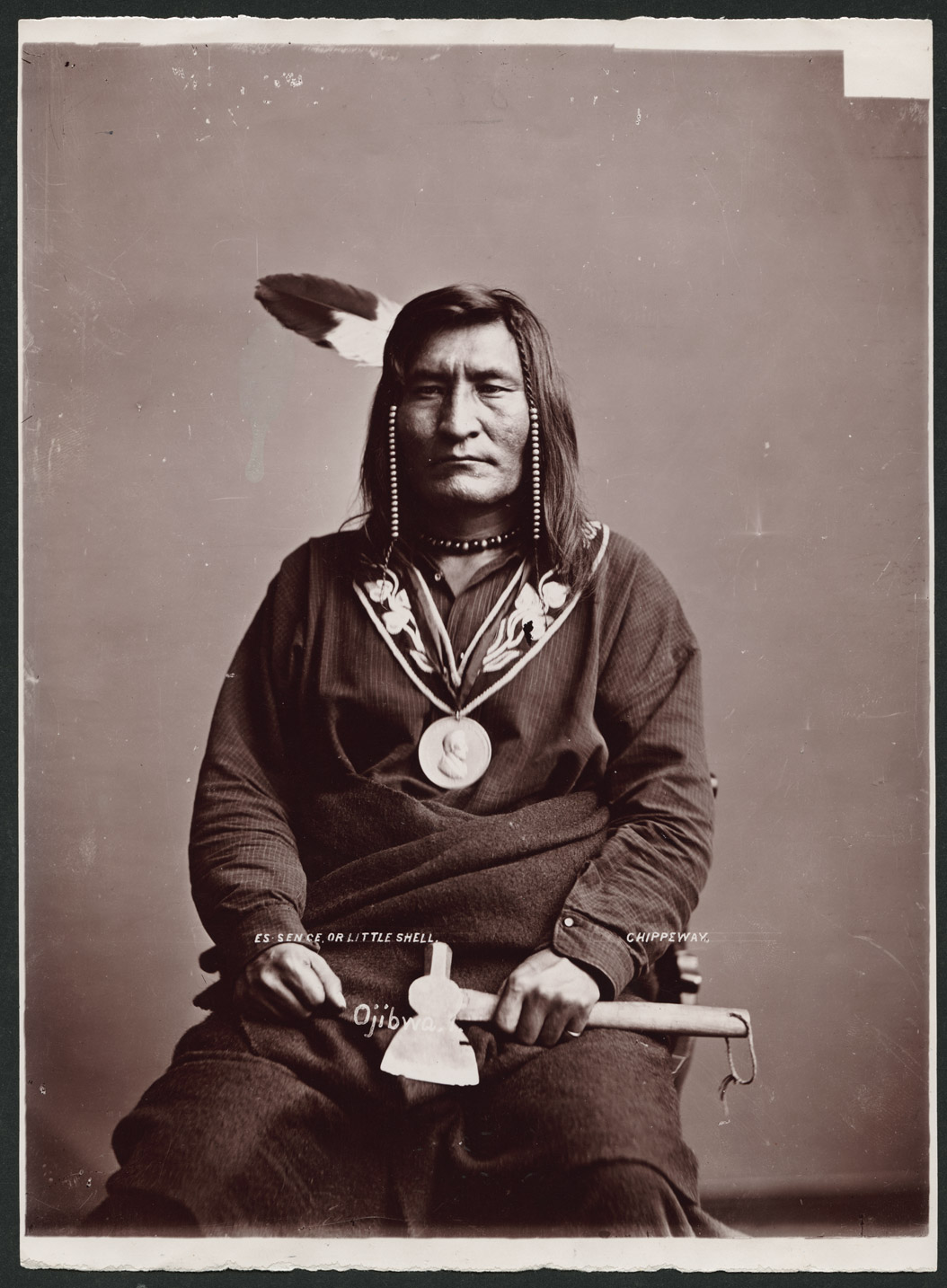

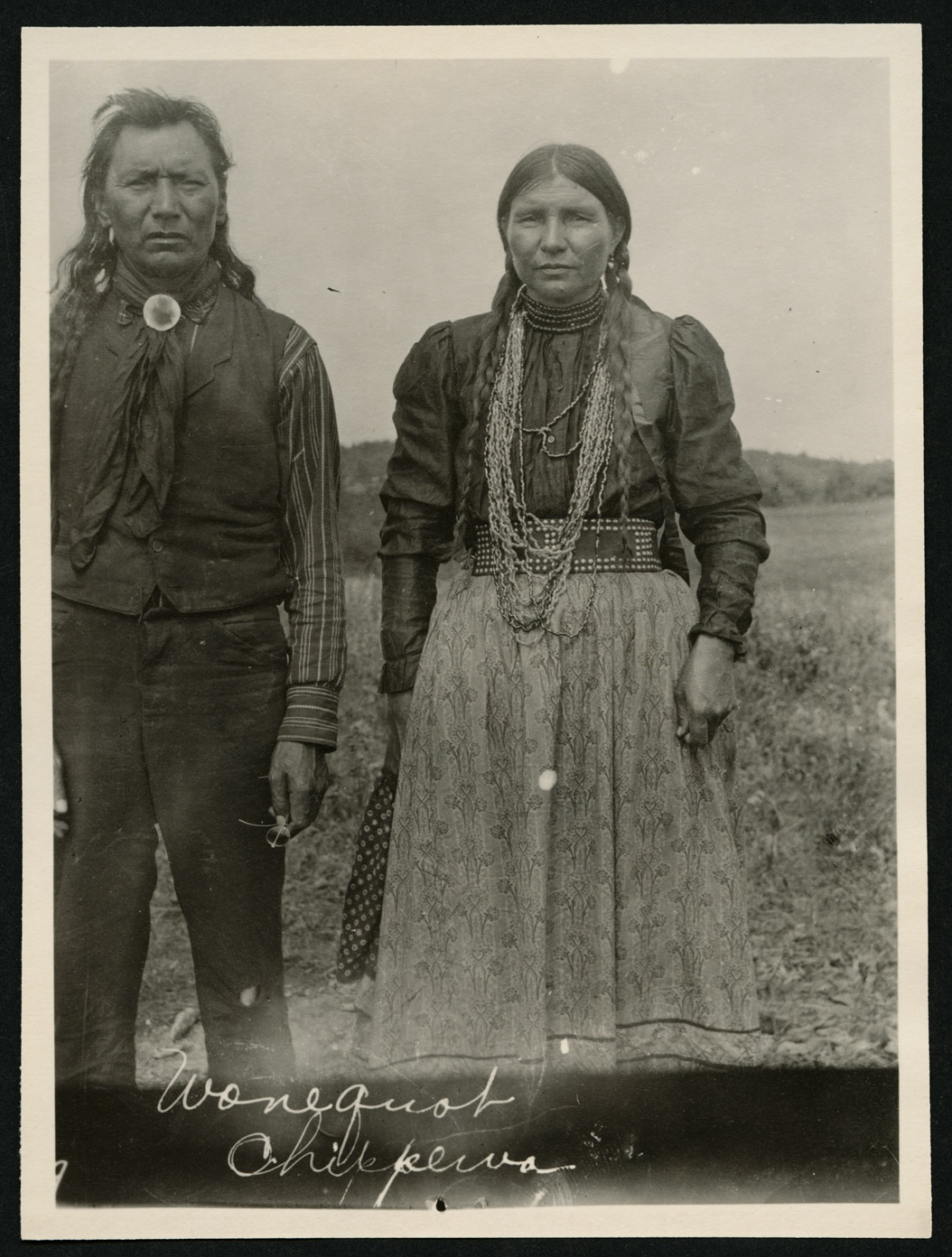

Another treaty council took place in 1863 between the Pembina Chippewas (those who lived west of the Red River and north of the Goose River), the Red Lake Chippewas (in northwestern Minnesota), and the federal government. The place where they met, on the Red Lake River, was called the Old Crossing. Little Shell (See Image 18) and Red Bear (See Image 19) represented the Pembina Band of Chippewas. Under pressure from people who wanted to own and farm land in northern Dakota Territory, the federal government asked the Chippewas to give up, or cede, nearly 9 million acres. All of that land was in northern Dakota Territory.

In the 1880s, President Chester A. Arthur reduced the size of the Turtle Mountain Reservation two more times. (See Map 10) Before reducing the reservation, the president first tried to remove the Chippewas from the Turtle Mountains and Pembina regions. President Arthur wanted to send the Chippewas to the White Earth Indian Reservation in Minnesota. He also wanted to send some Chippewa families to Fort Berthold to live with the Mandans, Hidatsas, and Arikaras. A few families went to White Earth, but many Chippewas refused to leave their homeland.

In 1882, President Arthur issued an executive order which created a reservation of 20 townships (460,800 acres.) This area was about the size and shape of present-day Rolette County. Then, on March 29, 1884, President Arthur signed another executive order reducing the size of the reservation to two townships (46,080 acres.) (See Document 28)

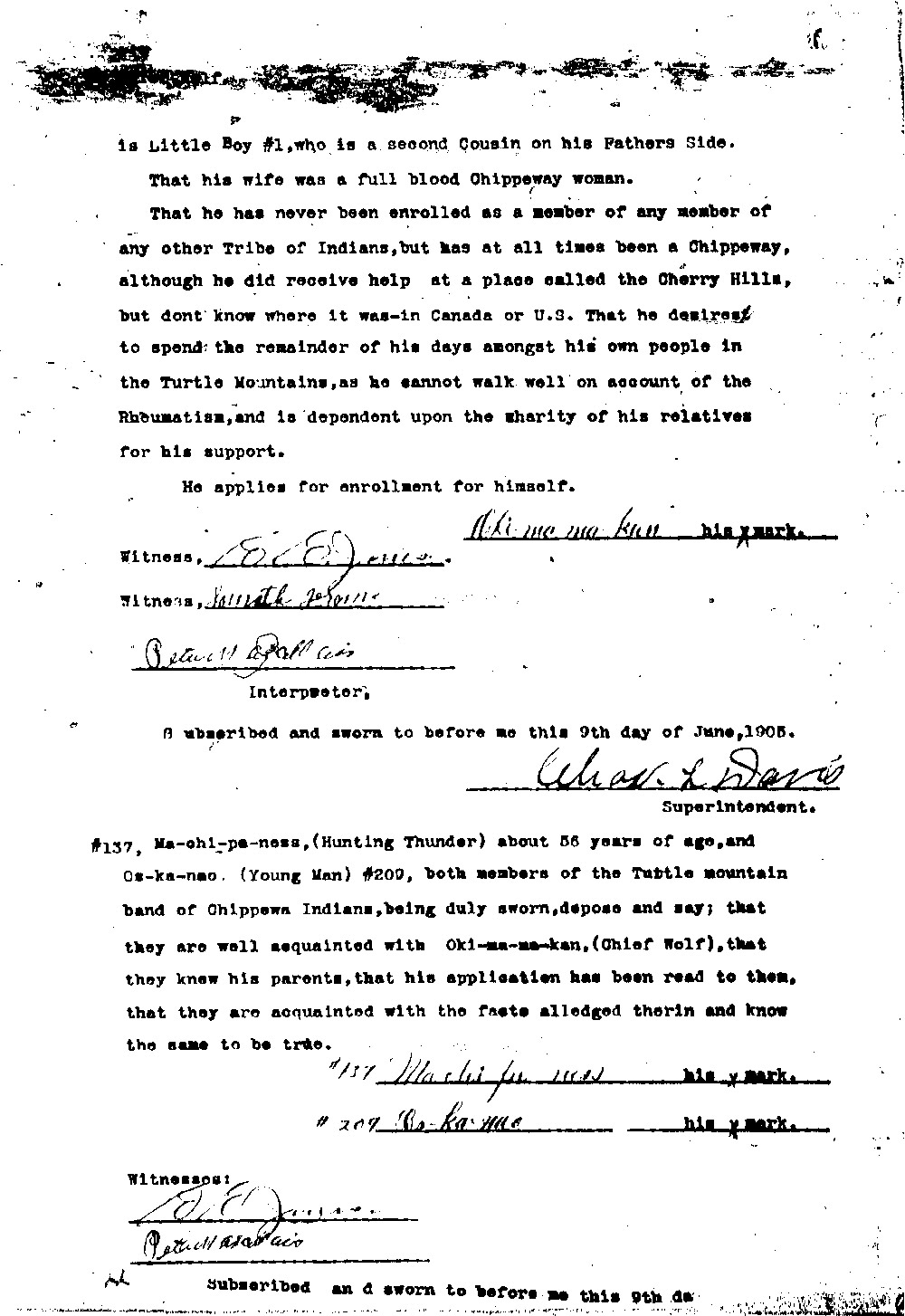

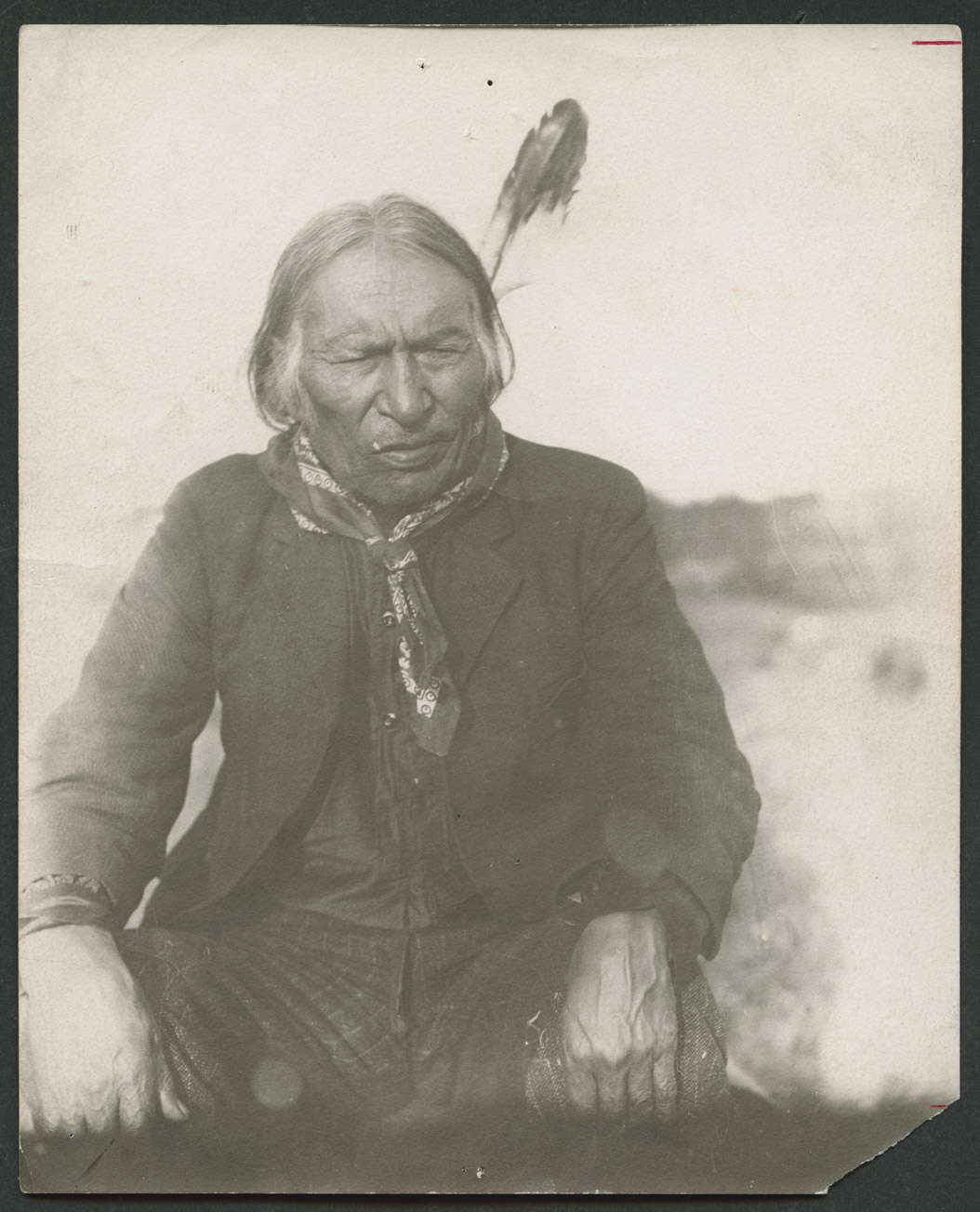

This area was too small for the Chippewa people. The federal government did not take into consideration several important factors when counting the population of the tribe. The Chippewas had often crossed the Canadian border as they hunted or moved their homes. The federal government did not want to count those who went to Canada as part of the Turtle Mountain band. In addition, many Chippewa women had married English or French fur traders. Their children were not full-blooded Chippewa. They were called Métis. U. S. government officials did not countIn 1892, the federal government took a census of the Turtle Mountain Reservation. The census recorded 25 full-blood families in the Turtle Mountain region. The Chippewas argued that the census process was not properly completed. Little Shell, a leader of one group of Chippewas, and his followers were not counted. Though Little Shell and others protested the incompetence of the census takers, 520 people were removed from the tribal rolls. Many of these people had to move to Montana to find a new home. Métis as part of the population of the Chippewa nation and wanted all Chippewas of Canadian origin to return to Canada.

The reservation of two townships was much too small for the Chippewas and the Métis. The government recognized this and made provisions for some Chippewas at Trenton (in present day Williams County) and in Montana.

In September, 1892, Porter J. McCumberPorter J. McCumber (1858 –1933) was a lawyer who had served in the Dakota Territorial House and Senate before statehood. In 1899, he was elected to the U. S. Senate where he served until 1923. He is best remembered as the co-sponsor of the Fordney-McCumber Tariff. and other federal commissioners met with the Chippewa Council. (See Image 20) They reached an agreement over land and compensation for the Chippewas’ land cessions. Little Shell and his followers were purposefully excluded from the treaty discussions. Though Little Shell hired attorney John B. Bottineau to represent his band, he was not allowed to participate in the council.

The members of the council that met with McCumber and the other commissioners were picked by John Waugh, the federal agent in charge. They were known as the Council of Thirty-two. They were not chosen by the tribe.

Though Little Shell traveled to Washington, D.C. to file a protest about the procedures used in reaching the McCumber agreement, the agreement was accepted (with some changes) by Congress in 1904. The Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewas received $1,000,000 for the 9,000,000 acres they ceded.

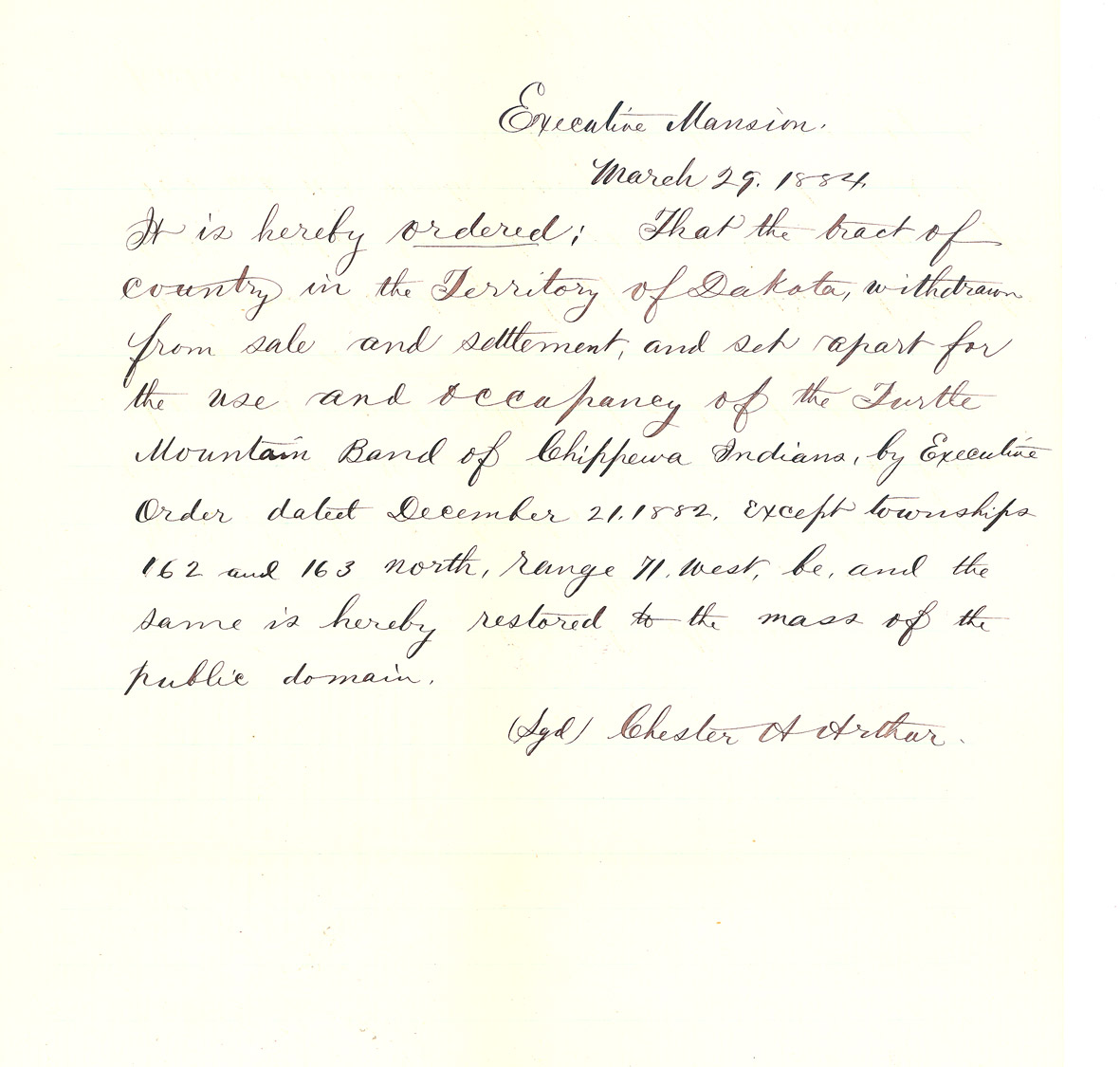

Document 28 Transcription

Executive Mansion

March 29, 1884

It is hereby ordered: That the tract of country in the Territory of Dakota, withdrawn from sale and settlement, and set apart for the use and occupancy of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewas Indians, by Executive Order dated December 21, 1882, except townships 162 and 163 north, range 71 West, be, and the same is hereby restored to the mass of the public domain.

(sgd) Chester A. Arthur

Why is this important? The federal government’s treatment of the Chippewas was harsh. They lost so much land that the tribe had to split up. Relatives were separated and the political power of the tribe was diminished. Those who were excluded from the roll of tribal members were unable to draw rations or collect annuities. Starvation caused the deaths of many Chippewas both before and after the McCumber Agreement. Because the agent, not members of the tribe, chose the Council of Thirty-two, many Chippewas have argued that the agreement was not legal. The price the Chippewas received for their land was so low that the McCumber agreement is often called the Ten-Cent Treaty.

Allotment

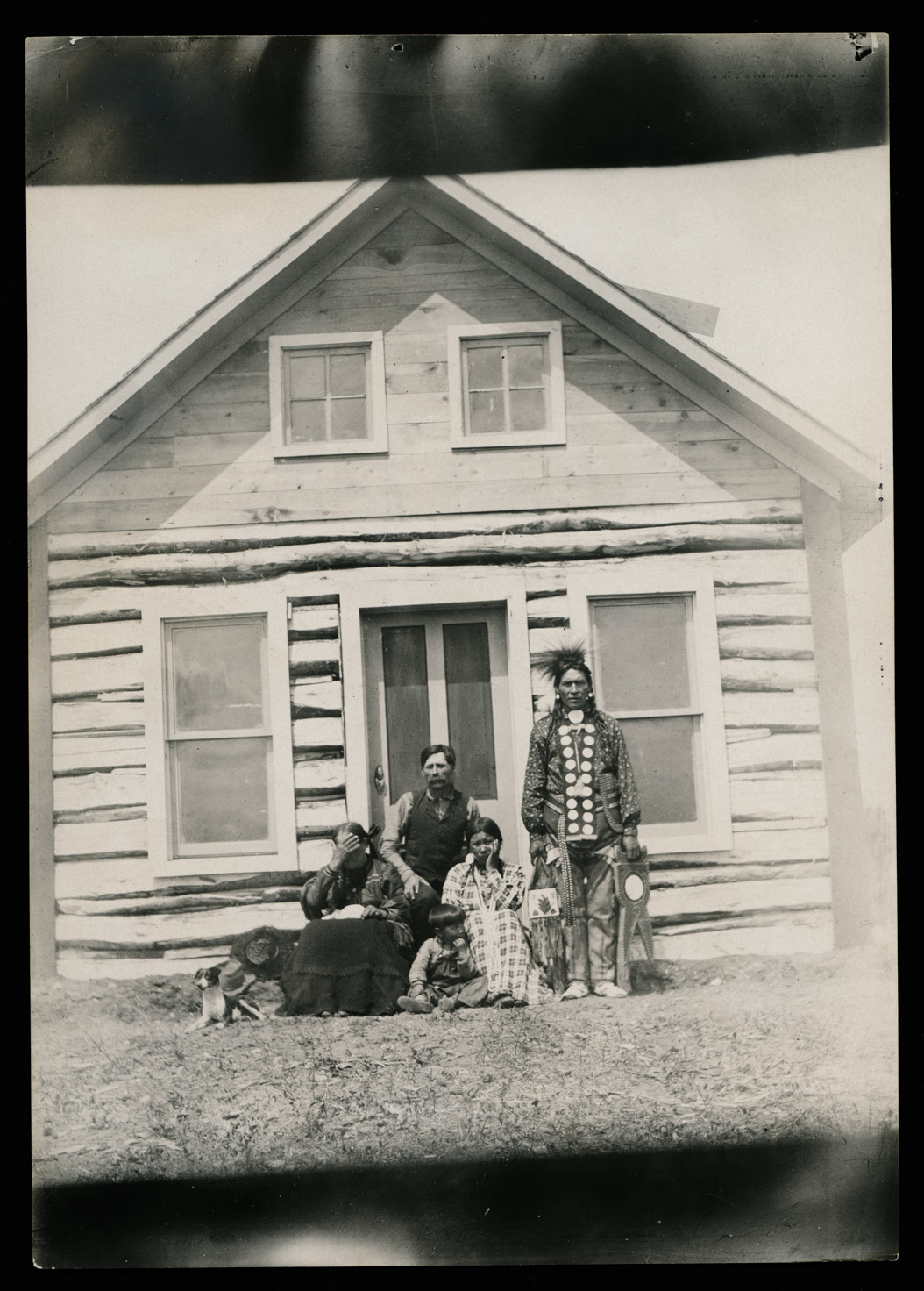

The Turtle Mountain Reservation was allotted in the same way as the other reservations in North Dakota. Allotment was imposed on the Turtle Mountain Chippewas in 1904 when Congress approved the McCumber Agreement. (See Image 21)

Most of the allotments at Turtle Mountain were for agriculture. That means that an adult male received 160 acres of land. The Turtle Mountain reservation, however, was so small (6 miles long and 12 miles wide) that there was not enough land for the residents of the reservation to receive allotments.

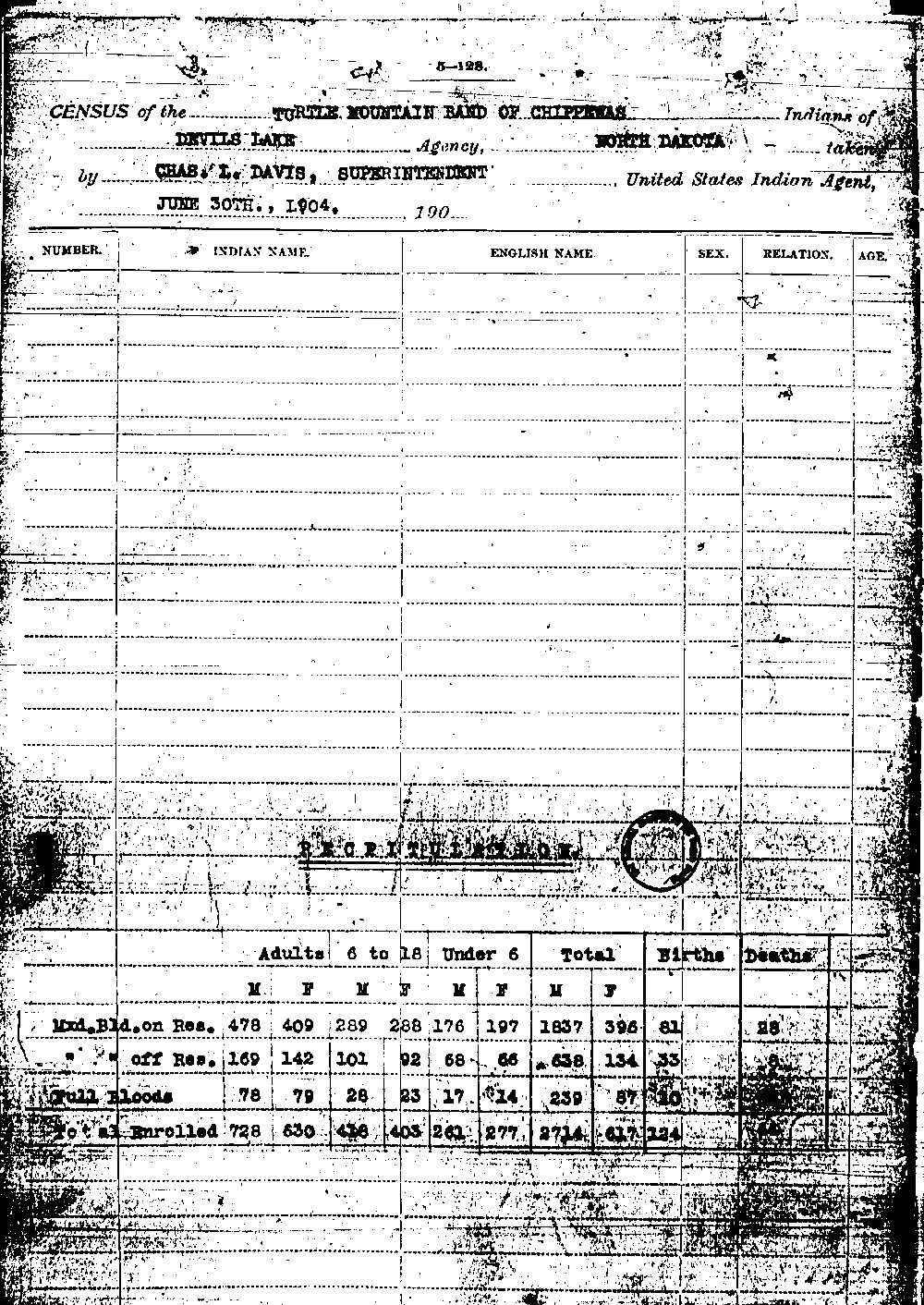

Simple math explains the problem. In 1904, the census counted 556 adult Chippewa men (full-blood and mixed blood) living on the Turtle Mountain Reservation. (See Document 29) The reservation was composed of two townships which is a total of 46,080 acres of land. If every adult male received an equal portion of land in those two townships, the portion of land to each would be 82.8 acres. This calculation, however, it does not take into account lakes, sloughs, and other places where a person cannot build a house or raise crops.

The allotment law (the Dawes Act) required that each adult male should receive 160 acres (for agriculture.) Each woman and each child under 18 received between 40 and 80 acres of land. In order to accommodate the population of the Turtle Mountain Chippewa, the government had to make allotments off the Turtle Mountain reservation in the public domain. (See Image 22)

Many Chippewas went to the Fort Totten Indian Agency at Devils Lake where they lived among the Dakotas. Others went to the Trenton Service Area. Many others went to Montana or to scattered allotments around North and South Dakota.

For some Chippewas, the allotments were too far away from their homeland and their families. They did not move to their allotments. Some sold the land, and others lost their land to fraud because they did not live on the land. (See Document 30)

By 1930, there were 979 allotments for Chippewas in Montana and 178 more outside of Rolette County in North Dakota.

Why is this important? Allotment changed the way American Indians lived. Before allotment, the Chippewas lived in close communities. Families could rely on their relatives who lived nearby. Governing councils were able to meet regularly. After allotment, families who accepted their allotments and moved away to live on their land were separated from other members of their families. Those who refused to move faced over-crowding and poverty.