Introduction

The Standing Rock Sioux Reservation is situated in North Dakota and South Dakota. The people of Standing Rock, often called Sioux, are members of the Dakota and Lakota nations. “Dakota” and “Lakota” mean “friends” or “allies.” The people of these nations are often called “Sioux,” a term that dates back to the 17th century when the people were living in the Great Lakes area. The Ojibwa called the Lakota and Dakota “Nadouwesou” meaning “adders.” This term, shortened and corrupted by French traders, resulted in retention of the last syllable as “Sioux.” There are various Sioux divisions and each has important cultural, linguistic, territorial, and political distinctions.

The Dakota people of Standing Rock include the Upper Yanktonai in their language called lhanktonwana which translates “Little End Village” and Lower Yanktonai, called Hunkpatina in their language, “Campers at the Horn” or “End of the Camping Circle.” When the Middle Sioux moved onto the prairie they had contact with the semi-sedentary riverine tribes such as the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara. Eventually the Yanktonai displaced these tribes and forced them upstream. However, periodically the Yanktonai did engage in trade with these tribes and eventually some bands adopted the earthlodge, bullboat, and horticultural techniques of these people, though buffalo remained their primary food source. The Yanktonai also maintained aspects of their former Woodland lifestyle. Today Yanktonai people of Standing Rock live primarily in communities on the North Dakota portion of the reservation.

The Lakota, the largest division of the Sioux, subdivided into the Ti Sakowin or Seven Tents and Lakota people of the Standing Rock Reservation included two of these subdivisions, the Hunkpapa which means “Campers at the Horn” in English and Sihasapa or “Blackfeet,” not to be confused with the Algonquian Blackfeet of Montana and Canada which are an entirely different group. By the early 19th century, the Lakota became a northern Plains people and practically divested themselves of most all Woodland traits. The new culture revolved around the horse and buffalo; the people were nomadic and lived in tepees year round. The Hunkpapa and Sihasapa ranged in the area between the Cheyenne and Heart Rivers to the south and north and between the Missouri River on the east and Tongue to the west. Today the Lakota at Standing Rock live predominantly in communities located on the South Dakota portion of the reservation.

Lakota Migration

|

Originally located in the Great Lakes, or Woodland area, the people were allied in what was known as the Seven Council Fires or Oceti Sakowin. This was comprised of the Santee division (Dakota speakers) with four groups, the Middle division (Nakota speakers) with two groups, and the Teton or Western division (Lakota speakers) originally consisting of one group. These subdivisions were not culturally distinct from each other in their Woodland home, but became more distinct as the people moved westward. In the Woodland region the people were semi-sedentary and their Woodland economy was based on fishing, hunting, gathering, and some cultivation of corn. In the 17th century the Sioux were pushed westward by tribes, particularly the Ojibwa and Cree, who obtained guns through the French fur trade. The Teton and Middle Sioux began a trek westward with the Teton in the lead. With the emergence onto the Plains the people became almost totally involved in a buffalo hunting economy. The buffalo supplied the main source of food as well as many material needs such as housing, clothing, and implements. With the acquisition of the horse in the same period, the Teton quickly developed a culture that centered around the horse and buffalo. By 1750 the Middle Sioux were settled along the Missouri River while the Teton pushed farther west into the Black Hills and beyond to present-day states as Nebraska, Wyoming, and Montana. By the early 19th century, political and cultural differences between the Sioux groups became pronounced and true Eastern, Middle, and Teton (Western) divisions emerged.

Both the Dakota and Lakota at Standing Rock relied almost exclusively on the buffalo as a major source of food, shelter, and material items. Both groups had complex spiritual ceremonies, and placed much emphasis on family and doing things that benefitted the people rather than the individual; these cultural and spiritual values remain important among the people to the present day. Once the people acquired the horse, in the mid 1700s, there was an impact on the material culture as well as the social customs of the people. Tepees became larger, there was greater mobility, and hunting became more productive. Additionally, the horse had a direct impact on the integration of the warfare in the fabric of the people’s lives. It is important to understand the main object of Plains Indian warfare was never to acquire land or to control another group of people. Plains Indian warfare focused on raiding other tribes’ camps for horses and acquiring honors connected with capturing horses. In these raids, very much like contests, men sought to out-smart the enemy and gain individual honors by counting coup, or striking the enemy with the hand or a special staff. Plains warfare emphasized out-smarting the enemy, not killing them. With the advent of the horse onto the Plains, warfare traditions became institutionalized among tribes. This style of warfare, described by one author as comparable to a rough game of football, changed dramatically after encounters with the U.S. Army in the 1850s.

These lifeways and warfare customs were followed until the discovery of gold in California in 1849. Up until this time the U.S. government considered the west a “permanent Indian frontier”—an inhospitable land with little economic value inhabited by Indians. In the early 1850s, overland travelers who were enroute to gold fields began to cross through Lakota territory. However, the discovery of mineral wealth in the west caused the U.S. to extend its boundaries to the Pacific Ocean, encroaching on the Indian lands and threatening the buffalo herds. This in turn set off a series of confrontations between whites and Indians of the trans-Mississippi West. Fortune seekers moving along the Platte River Road cut right through traditional Lakota territory and although generally left alone, the white travelers were frightened by the turmoil and commotion caused by the intertribal raids and they demanded government protection.

The 1851 Fort Laramie Treaty

As a result, in 1851 the federal government brought many of the Plains tribes together at Fort Laramie, including many Lakota and Dakota bands, and sought to establish peace among the tribes so settlers could continue to move across the area and not fear for their safety. The government solution was to assign each tribe a defined territory where they were to remain. Government negotiators had the various Indian nations appoint head chiefs to these councils so they could deal with a small group of men rather than the entire nations. This sort of negotiation was meaningless to the Lakota, Dakota, and other Indian nations. Decision-making among the Lakota and Dakota was based on participation of all until consensus was reached, and in this form of democracy a few men could not speak for all or bind all people to treaty promises. Nonetheless, the government insisted on negotiating with appointed chiefs and through the treaty process sought to define its relationship with the various tribes. The 1851 Fort Laramie Treaty defined territory for each tribal group in order to end intertribal rivalry and it permitted travelers and railroad workers on the Platte River Road. The Yanktonai, covered by an earlier 1825 treaty, were omitted from the treaty because their traditional areas were far removed from the overland route to the Pacific Coast which the treaty aimed to safeguard.

Ultimately, many Lakota and Dakota never knew of the existence of the 1851 Treaty and they continued their intertribal raiding. The U.S. regarded this as a breach of treaty, however, and government could not compel its own countrymen to respect the treaty either. Travelers continuously passed through defined Indian territories and ignored the treaty though no major incidents occurred until the numbers of travelers increased.

A number of events that occurred in 1861 directly impacted both the Dakota and Lakota who would later to be part of the Standing Rock Reservation. In 1861 when the Dakota Territory was established, the Yanktonai and Hunkpatina occupied much of the area east of the Missouri River. Events which followed the Minnesota Indian War of 1862 rapidly changed this. Also, in 1861, gold was discovered at the headwater of the Missouri River and this had an immediate impact on the Lakota living on the west side of the Missouri River.

The Santee, located on an ever-shrinking homeland in Minnesota, were dissatisfied with federal policies and when they received no redress of their grievances some men precipitated a confrontation in 1862. Some Santees raided settlements, attacked a military installation, and ultimately caused 40,000 settlers to flee. Federal response to the trouble was quick and all Indians in the area were considered potentially dangerous, so many Indian people who had no connection to the troubles were punished. Fearful of retribution, many of the Santees fled into Dakota Territory and Canada. Settlers on the Dakota frontier, fearful of trouble, demanded government protection. Generals Henry Sibley and Alfred Sully were assigned to round up “hostiles” in the Dakotas. They found no “hostiles” but followed some hunting bands at various times. Despite the apparent peace in the Dakotas, wild rumors of dangerous Indians continued and the military was under great public and political pressure to keep up its campaign.

Whitestone Hill

Two military expeditions entered Dakota Territory during the summer of 1863. One column of soldiers was led by General Henry H. Sibley and originated from Minnesota. The other expedition, commanded by General Alfred Sully, followed the Missouri River north from Iowa. Sully’s campaign culminated in the Battle of Whitestone Hill.

In early September 1863, General Sully discovered a large hunting camp of Yanktonai at Whitestone Hill. These people had nothing to do with the Minnesota problems and they were not posing a threat to homesteaders in Dakota Territory. The Yanktonai people at Whitestone Hill were preparing food for the winter months ahead. Sully’s troops never determined who these people were and on September 3, 1863, 650 soldiers attacked the Yanktonai, killing at least 300, including many women and children. Twenty soldiers were killed, many caught in army crossfire. The Yanktonai who were able fled the area, abandoning all their household goods and stores of food. The scene of the battlefield and Indian camp the next day was recorded by F.E. Caldwell, a soldier with the Second Nebraska Cavalry:

Tepees, some standing, some torn down, some squaws that were dead, some that were wounded and still alive, young children of all ages from young infants to eight or ten years old, who had lost their parents, dead soldiers, dead Indians, dead horses, hundreds of dogs howling for their masters. Some of the dogs were packed with small poles fastened to a collar and dragging behind them. On the poles was a platform (travois) on which all kinds of articles were fastened on—in one instance a young baby. (Jacobson, p. 99)

The next two days Sully rounded up Yanktonai survivors who were in the vicinity of the battle because they had no horses. They were taken and held as prisoners. Sully also ordered the destruction of all food and equipment left behind by the Yanktonai. Caldwell described that process:

Sully ordered all the property destroyed, tepees, buffalo skins, and all their things, including tons and tons of dried buffalo meat and tallow. It was gathered in wagons, piled in a hollow and burned, and the melted tallow ran down the valley into a stream. Hatchets, camp kettles, and all things that would sink were thrown into a small lake. (Jacobson, p. 101)

Sully’s men were congratulated by the U.S. for their distinguished conduct, and the Indian story never came out though it was told among their own people. In November 1863, Sam Brown, a 19-year-old interpreter at Crow Creek, presented the Indian side of Sully’s battle at Whitestone Hill in a letter to his father:

I hope you will not believe all that is said of “Sully’s Successful Expedition” against the Sioux. I don’t think he aught to brag of it at all, because it was, what no decent man would have done, he pitched into their camp and just slaughtered them, worse a great deal than what the Indians did in 1862, he killed very few men and no hostile ones prisoners... and now he returns saying that we need fear no more, for he has “wiped out all hostile Indians from Dakota.” If he had killed men instead of women & children, then it would have been a success, and the worse of it, they had no hostile intention whatever, the Nebraska Second pitched into them without orders, while the Iowa Sixth were shaking hands with them on the other side, they even shot their own men. (Jacobson, p. 105)

(For Sioux Pictograph of the Whitestone Hill Battle, See Document 1.)

Sully and his troops wintered in the newly constructed Fort Rice while plans were being launched to force the Indians to cede large areas of their territory. In July 1864, Sully set out for the Killdeer Mountains where Yanktonai, Sihasapa, Hunkpapa, and other Dakota were in a large hunting camp. On July 23, 1864, Sully’s troops, aided by artillery, killed about 100 Indians and the people from their camp and forced them to abandon all their food and household goods. Again, all Indian property was destroyed. This is known as the Battle of Killdeer Mountains. Sully chased down some of the stragglers from the battle along the Yellowstone River in the Badlands, and in August 1864, soldiers attacked some of the survivors of the Killdeer Mountains. By fall, 1864, the commander at Fort Sully assessed the situation of the Yanktonai, Hunkpatina, and others,

“Their severe punishment in life and property for the last two years is an excellent groundwork for a peace I believe would be lasting…” (Jacobson, pp. 110–111)

With little other recourse, the Yanktonai signed a treaty with the U.S. government at Fort Sully in October 1865. The tribes agreed to be at peace with the U.S. and other tribes, withdraw from overland routes through their territory, and in return for these concessions the U.S. provided monetary reparation and agricultural implements to the tribes.

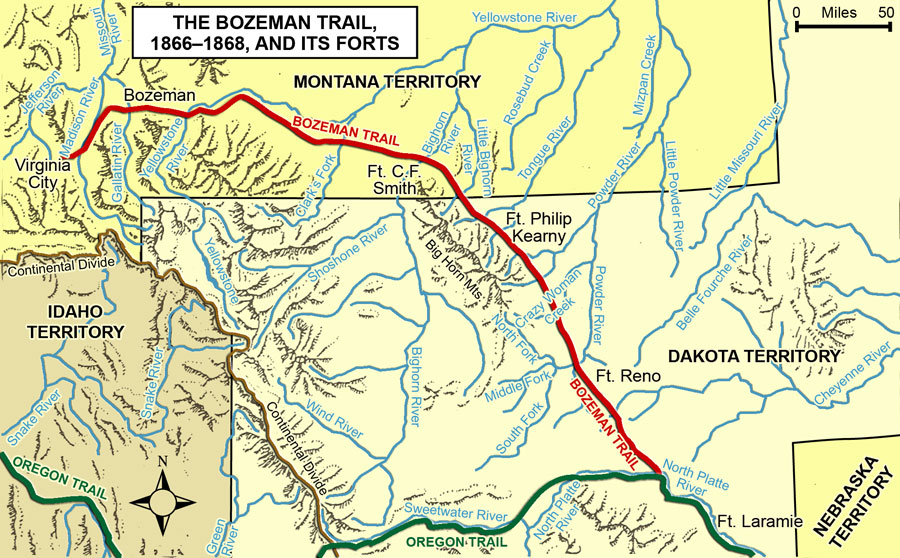

In 1861 the Union was desperate for gold and silver to fund the Civil War effort. Indian rights were not a consideration when the destiny of the Union was at stake, so when gold was discovered in Montana, little was done to hold back the flood of fortune-seekers who overran Sioux treaty lands along the Bozeman Trail.

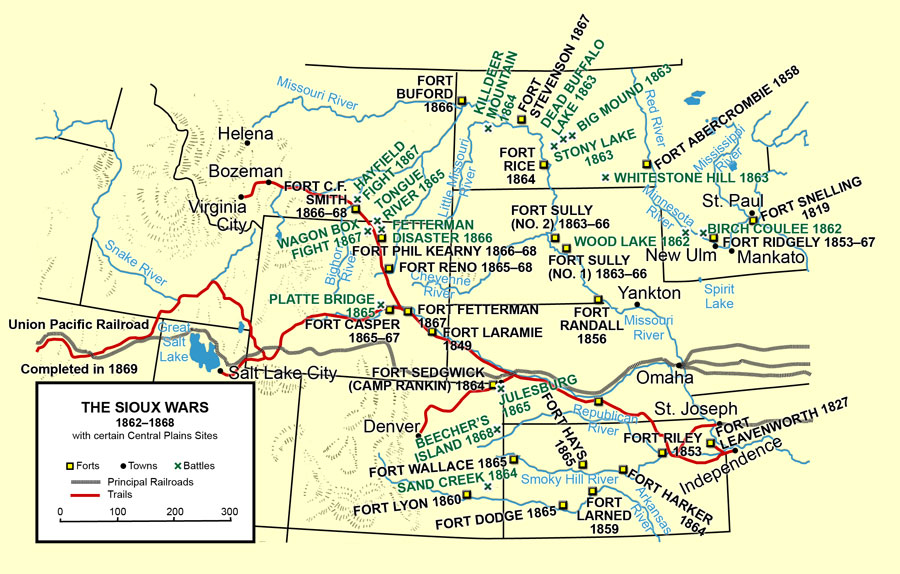

Continued traffic through Sioux lands caused disruption in the lifeways of the people and cut through the heart of the Sioux buffalo ranges in the Powder River area. The Sioux repeatedly objected to intrusions in their territory and demanded government recognition of the 1851 Fort Laramie Treaty. Ultimately their protests fell on deaf ears. With no peaceful solution in sight the Sioux began to retaliate against trespass in their country. The government’s need for gold coupled with demands for protection by travelers along the Bozeman Trail increased so the army moved in to protect non-Indian people, property, and rights-of-way through Dakota-Lakota territory. Thus began the era commonly referred to as the Plains or Sioux Wars of 1865–1876. (See map, page 6, from Utley’s The Indian Frontier.)

The 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty

|

Rather than addressing the issue of trespass in Sioux country, the government responded with talk of yet another treaty with the Sioux. Historically the federal government has had a poor record of honoring treaties negotiated with Indian tribes. As the need for land or resources developed, the federal government simply moved to change the provisions of previous treaties. Treaties are legal documents the United States government, as a sovereign nation, negotiates with another sovereign nation. Initially, treaties with tribal nations sought to define the relationship that existed between the U.S. and a tribe, but as time went on, the U.S. used treaties as a way to extinguish Indian rights to ancestral homelands. And so when Sioux treaty lands were overrun with goldseekers, the U.S. simply sought to modify rather than honor the existing treaty. Tensions along the Bozeman Trail continued to escalate. Then, in June of 1866, the U.S. held a talk at Fort Laramie with various Lakota bands. The government promised many gifts and benefits to the Sioux and glossed over the object of the government’s interest—to negotiate a new treaty which would close off the Powder River area and the Bozeman Trail to the Indians in order to insure continued gold supplies and emigration into Montana. In the middle of the treaty talks, a military man informed some of the Indian negotiators he had orders to build forts along the Bozeman Trail to protect settlers moving into Montana. The Sioux were outraged at this news, as it was in direct violation of the 1851 Treaty and had not been mentioned in the council meetings. Thus the treaty talks ended abruptly. Red Cloud delivered a speech about white betrayal and treachery and led the Sioux delegation north vowing to fight all who invaded their territory as set down in the 1851 Treaty.

The troubles in 1866–1868 in the Powder River region, often called “Red Cloud’s War,” resulted in a clear victory for the Lakota. The Lakota had denied the Bozeman Trail to virtually all immigrant travel. Army supply trains had to fight their way through, and soldiers were bottled up in their forts. The Indians had little need to negotiate a treaty and so ignored all government overtures to do so. Finally in 1868 the soldiers abandoned their forts along the Bozeman Trail as a way to restart treaty negotiations. By this time the U.S. government was set on confining the Sioux to proscribed territory but first it needed a treaty.

Establishment of the Great Sioux Reservation

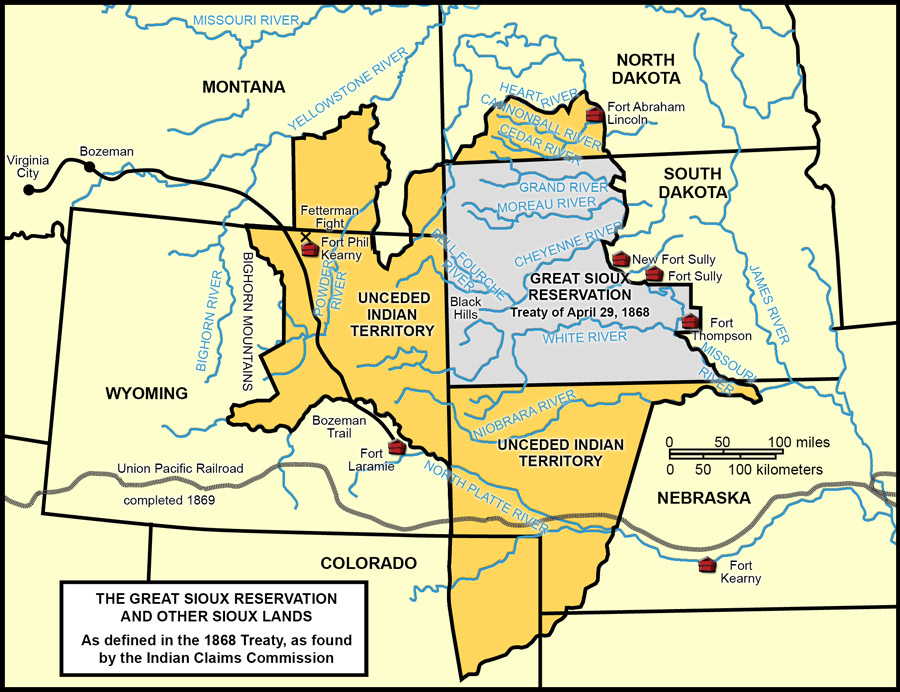

Government policy by the mid 1860s was to confine all Indians to defined land areas called reservations. The United States government proposed what became known as the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty to deal with the Sioux issue. This treaty proposed to:

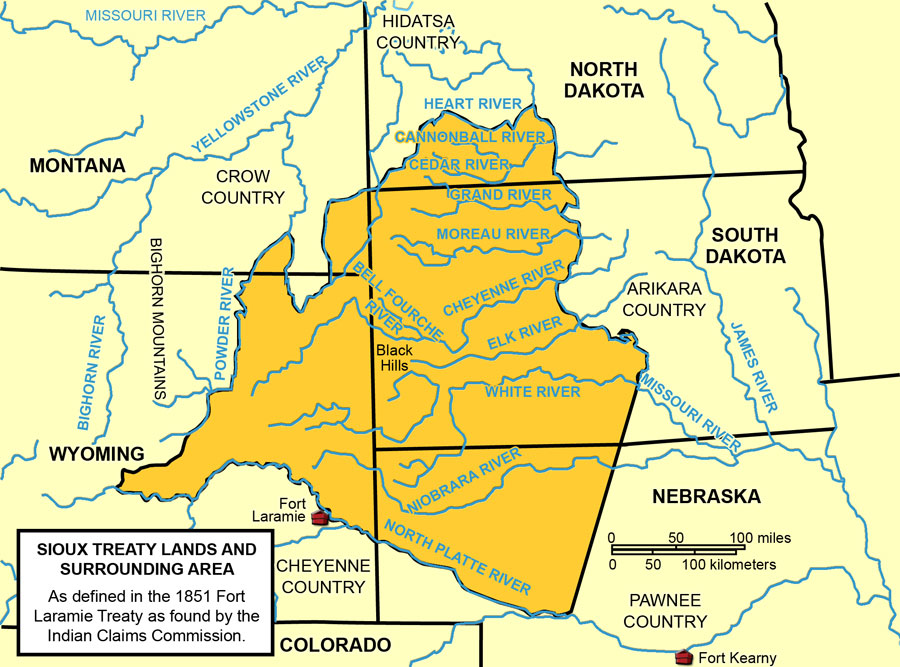

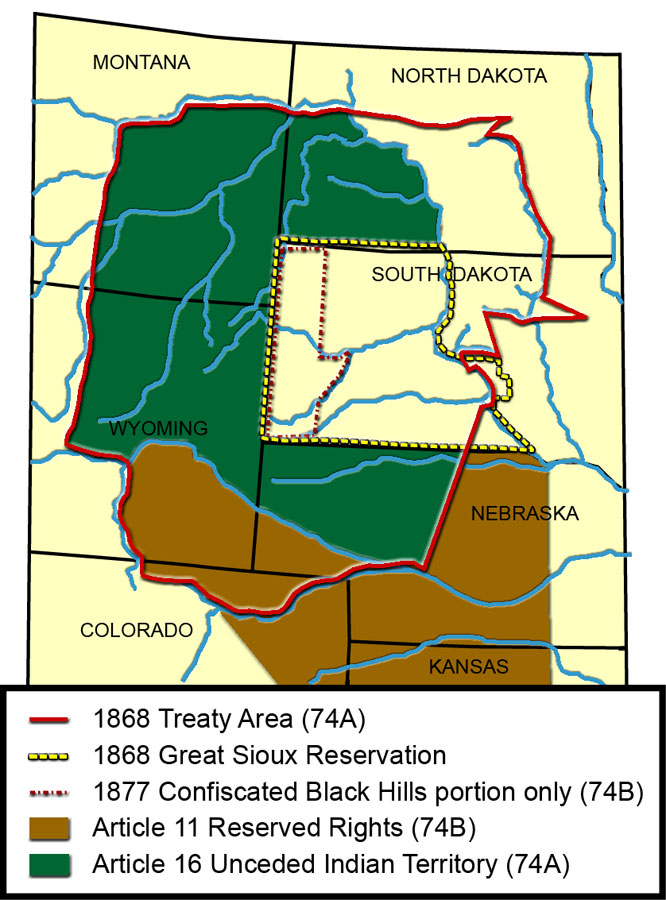

- Set aside a 25 million acre tract of land for the Lakota and Dakota encompassing all the land in South Dakota west of the Missouri River, to be known as the Great Sioux Reservation;

- Permit the Dakota and Lakota to hunt in areas of Nebraska, Wyoming, Montana, and North Dakota until the buffalo were gone;

- Provide for an agency, grist mill, and schools to be located on the Great Sioux Reservation;

- Provide for land allotments to be made to individual Indians; and provide clothing, blankets, and rations of food to be distributed to all Dakotas and Lakotas living within the bounds of the Great Sioux Reservation.

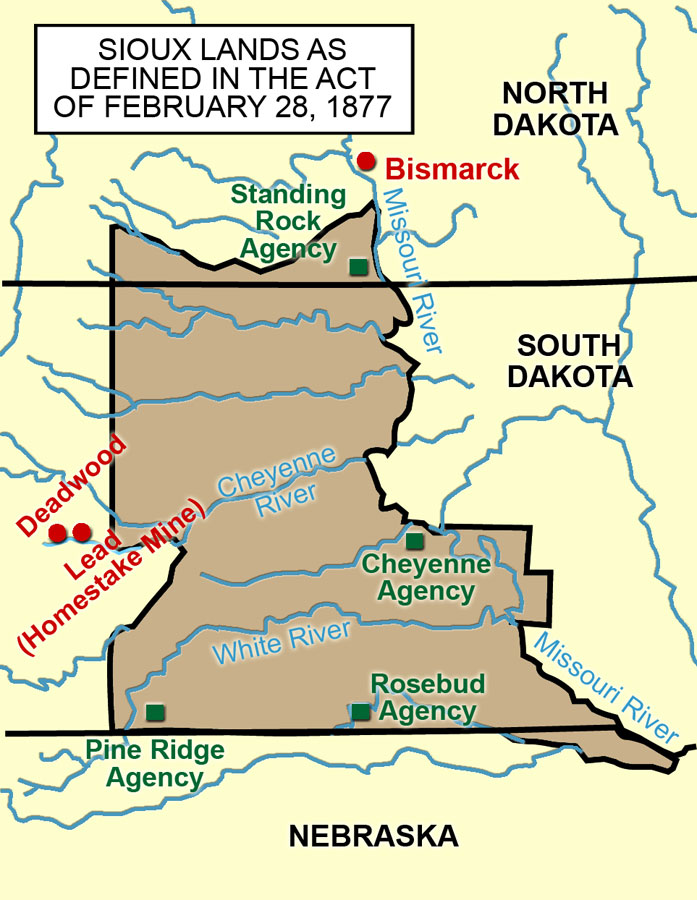

found by the Indian Claims Commission. Map adapted from Lazarus, Great Sioux Reservation. (SHSND-ND Studies)

In return, if the Sioux agreed to be confined to this smaller land area, the federal government would remove all military forts in the Powder River area and prevent non-Indian settlement in their lands. The treaty guaranteed that any changes to this document must be approved by three-quarters of all adult Sioux males. Red Cloud seemed to have won his point since the forts along the Bozeman Trail were abandoned so, in good faith, he signed the treaty. Those Lakota and Dakota who lived south or east along the rivers also signed the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty because they were already living within or near the bounds of the newly established Great Sioux Reservation. However, three-quarters of the Sioux males did not sign this treaty. Most of the Lakota living north of Bozeman Trail including the Hunkpapa and Sihasapa bands, did not sign. In particular, Sitting Bull, a Hunkpapa, rejected all overtures to sign this treaty. Sitting Bull soon became a recognized leader of the Sioux who refused to give in to government entreaties to change their lifestyle and live in a confined area.

|

After the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty was negotiated some Hunkpapa, Sihasapa, and Yanktonai moved onto the northern part of the Great Sioux Reservation, the area designated for their bands. Yanktonai, under Two Bears, who lived and farmed on the east side of the Missouri River, refused to move across the river onto the new reservation because they had good land for farming. However, they maintained a friendly relationship with the agent. Many Lakota, among them many Hunkpapa, refused to recognize the 1868 Treaty saying it provided little to the people and pointed out non-Indians continued to use their land, and the government did not honor treaty provisions which promised rations, clothing, and schools. These people continued to live in their traditional areas in the un-ceded lands, followed the buffalo, and maintained their traditional lifeways.

As a way to monitor the Dakota and Lakota who lived on the vast Sioux Reservation, the federal government established agencies. In 1868 the Grand River Agency was established on the west bank of the Missouri River above the confluence of the Grand and Missouri Rivers to handle matters on the northern part of the Great Sioux Reservation. As protection to the Indian agent and support staff, army forts were built near the agencies. In 1870 a fort was built near the Grand River Agency. Bands served by the Grand River Agency were primarily Yanktonai, Hunkpapa, and Sihasapa.

U.S. federal Indian policy in the 1870s sought to enforce the reservation system and to confine Indians to certain areas apart from settlers; federal policy also encouraged Indians to abandon their nomadic lifestyle in favor of farming. By confining Indians within designated reservation areas, the federal government relentlessly pursued a policy described as “Christianizing and civilizing the savages.” The goal of this policy was to “make Indians fit to live in the presence of the [white man’s] civilization.” This would be accomplished by replacing Indian spiritual tradition, cultural values, and lifeways with those of mainstream American society. In fact, as a way to encourage Christianization of the Indians, the federal government assigned various religious denominations to administer the reservations beginning in 1869. By 1870 Standing Rock was run by Catholics. The various denominations established schools and generally carried out the “civilizing” policies of the federal government.

Those Lakota living off the reservation in the un-ceded territory complained bitterly when the federal government permitted the Northern Pacific Railroad survey crews into this area in direct violation of the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty. Sitting Bull opposed this incursion into Lakota lands and interference in Lakota life, and asserted his people’s rights to defend their homelands.

The U.S. government’s response to these complaints of treaty violations was to build more forts to protect settlers and railroad crews. Forts dotted the Missouri River near Indian settlements and treaty lands. Near the Grand River Agency, Forts McKeen and Abraham Lincoln joined Fort Rice along the Missouri River. The federal government continued to openly violate the 1868 Treaty throughout designated Sioux territory.

The most famous and well-documented violation of Sioux rights was the 1874 Black Hills expedition of geologists and soldiers under George Custer, who were sent in by the federal government to explore the Black Hills and report on the extent of gold deposits. The Dakota and Lakota angrily protested the direct violation of the 1868 Treaty. Although the government admitted this expedition was illegal, it justified the survey stating it was only to gain information about mineral wealth in the Black Hills.

Almost at once geological reports of gold in the Black Hills leaked to the general public and a stampede of miners poured into the area. By law these goldseekers were trespassing in area defined as Sioux country in the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty. Half-hearted attempts by the military to keep miners out of the area were unsuccessful, and by the spring of 1875 the Black Hills were overrun by prospectors. Rather than enforce the 1868 Treaty and remove intruders from the Black Hills as the Dakota and Lakota vehemently demanded, the federal government’s response was to call together a council to again change the terms of the treaty. This time the government proposed to purchase the Black Hills.

The Grand River Agency representatives to this council were highly irritated at the invasion of the Black Hills and initially refused to attend the council meeting. They made their case by saying, “It is no use making treaties when the Great Father [President] will either let white men break them or not have the power to prevent them from doing so.” (John Burke, to E.P. Smith, September 1, 1875, BIA) The Lakota and Dakota bands from all agencies overwhelmingly rejected any proposal to sell or negotiate away their rights to the Black Hills. Tension between the Indians and government officials were high, but past experience taught the tribes the government would not accept their decision not to negotiate away anymore rights or territories.

Establishment of Standing Rock Agency

At the time gold was discovered in the Black Hills, the United States government was beginning in earnest to implement its policy to confine all western Indians on reservations. The government wanted all Lakota and Dakota within the bounds of the Great Sioux Reservation and out of the un-ceded territories. In order to make the Grand River Agency more functional, the Indian agency and its army support moved 55 miles up the Missouri River to a high tableland at a point where the river was narrow and deep. This new site had a river landing accessible to steamboats, an abundance of cottonwood timber, and good farming land. This area was outside the bounds of the Great Sioux Reservation but an Executive Order signed March 16, 1875, extended the reservation’s northern boundary to the Cannonball River. Fort Yates became the military support for the agency and late in 1874 the agency officially became known as Standing Rock Agency.

Since the Standing Rock Agency’s new location at Fort Yates was to be a permanent location, the Yanktonai, under Two Bears, living and farming on the eastern side of the Missouri River were forced to move across the river. The federal agent at Standing Rock implemented government policies aimed at “civilizing” the Indians; these included encouraging Indians to construct log homes and take up farming. The federal government also distributed rations of food to all Indians living within the bounds of the Great Sioux Reservation. These rations consisted of flour, lard, bacon, sugar, coffee, and beef. Rations were used as a way to keep people on the reservation and discourage the people from pursuing a traditional lifestyle of hunting; only those Indians living on the reservation were eligible for rations. In time, when Indians changed to a farming economy the government planned to end the rationing system. As another way to encourage adaptation of the “white man’s civilization,” as it was referred to in government documents, the federal government distributed clothing, blankets, and cloth to the Indians on an annual basis. This, too, was done to discourage pursuit of the old lifestyle with cloth replacing leather for clothing. But more importantly to the government, the clothes made the Indians look more like their counterparts in the majority society and less like Indians. Nonetheless, winters were harsh and rations were often late so Indians continued to leave the reservation to hunt in the un-ceded territory as provided in the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty.

The Battle of the Little Bighorn

The flood of miners into the Black Hills continued unabated, and the federal government did little to discourage these trespassers. The Sioux refused to negotiate another treaty, so rather then uphold the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty the government instituted a policy that declared the ceded lands off-limits and sought to force all Dakota and Lakota living in the un-ceded areas between the Black Hills and Bighorn Mountains within the confines of the Great Sioux Reservation. In December 1875, the government plan became official policy. The people living in winter camps in the un-ceded territory were ordered to report to their agencies by January 31, 1876, or they would be regarded as hostile and the army would drive them in. The winter of 1875–1876 was bitterly cold, however, and runners were sent to the winter camps in the un-ceded lands to inform the people of this new policy. The runner from Standing Rock left in December 1875 and he did not return to the agency until February 11, 1876. He reported that Sitting Bull’s people were near the mouth of the Powder River and had received him well, but they could not come in at that time. At the very time the government was trying to gather Indians onto the Great Sioux Reservation many Indians settled at the Standing Rock Agency, and were given permission by the agent to go into the Powder River country to hunt since there was a shortage of food supplies and rations on the reservation. Due to the cold weather, these people did not return by the January 31st deadline so they too were considered hostile even though they had permission to be off the reservation.

The cold weather prevented the army from embarking on the planned winter campaign to round up the so-called hostiles. However, when warmer weather came the military prepared to converge on the Dakota and Lakota in the un-ceded lands and force them onto the Great Sioux Reservation. In June 1876, the military campaign against the Sioux became intense. Sitting Bull, a Hunkpapa, and Crazy Horse, an Oglala, were prominent leaders of the people living outside the bounds of the Great Sioux Reservation and they asserted their legal right to be in the un-ceded territory. In June, as was tribal custom, the Dakota and Lakota people came together in a large group to hunt and to conduct a sun dance ceremony. During the sun dance, Sitting Bull told of a strong image he saw, of many soldiers falling into camp and he saw a big Indian victory. Within days after the sun dance, on June 17, 1876, General Crook attacked Sioux and Cheyenne camped along the Rosebud River. The soldiers were held at bay until they finally retreated. This, however, was not the event foretold by Sitting Bull. The Dakota and Lakota bands moved their camp along the banks of the Little Bighorn River, and on June 25, 1876, Custer and his troops stumbled on a large Indian encampment that included many women, children, and old people. Custer ordered an attack and within 45 minutes all men under his command were dead. Fearful of reprisals after the Battle of the Little Bighorn the Indian camp divided and fled in many directions.

“Custer’s Last Stand,” as the fight was popularly known, shocked and outraged Americans, and brought a flood of soldiers into Indian country.

During the summer and fall of 1876, many Indians filtered back to their various agencies while those who stayed in the un-ceded lands were relentlessly hunted down by the army. In a tense meeting with government officials in October 1876, Sitting Bull refused to surrender and stated that the Great Spirit had made him an Indian, but not an agency Indian. Rather than go to the reservation, he led his people northward into Canada in January 1877.

In the fall and winter of 1876 and 1877, all Indians returning to their agencies had to surrender their guns and horses to the Army. At Standing Rock, all Indians who lived some distance from the agency had to move closer to the administrative office so the agent and soldiers could watch them. The Sioux were now confined to their reservation and were regarded as prisoners of war. Firm control was exerted on all the inhabitants of the Great Sioux Reservation, including those people at Standing Rock Agency.

The Taking of the Black Hills

In the late summer of 1876, partly in retaliation for the Battle of the Little Bighorn, the United States government moved to annex the Black Hills from the Great Sioux Reservation. According to the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty, three-quarters of the adult Sioux males had to approve this change so the federal government had to send commissions to each agency to explain the proposal and obtain the necessary signatures. By this point the Lakota and Dakota people were not willing to negotiate for more loss of land. The process was regarded as a sham; there was no true negotiation, the treaty commission was powerless to change the document—they could only carry concerns to the U.S. Senate who had final approval. And the Indians knew, through past experience, the Senate often ignored all Indian concerns or wishes.

At Standing Rock the government commission obtained only forty-eight signatures of men agreeing to relinquish the Black Hills, and the commissioners fared no better at the agencies. Despite the fact that the 1868 Treaty was legally binding and the Sioux overwhelmingly refused to sign the new treaty, the U.S. Congress ratified the 1876 Act in February of 1877, taking the Black Hills from the Dakota and Lakota and extinguishing their hunting rights in the un-ceded territory. Upon hearing of the annexation of the Black Hills, Henry Whipple, the government appointed chairman of the commission that was unsuccessful in obtaining consent of the Sioux to relinquish these lands and rights, said, “I know of no other instance in history where a great nation has so shamefully violated its oath.” The commission’s report to Congress elaborates with this statement and underscores the commission’s lack of power in the process:

Our country must forever bear the disgrace and suffer the retribution of its wrongdoing. Our children’s children will tell the sad story in hushed tones, and wonder how their fathers dared so to trample on justice and trifle with God. (BIA, Annual Report, 1876)

|

By 1877, the Indians at Standing Rock agency were left with no alternative but to try and accept conditions imposed on them by the government. Government control of the Sioux was harsh and unbending. Access to hunting grounds was firmly denied and with no horses or guns the people were forced to accept government food rations and clothing distributions. The government encouraged self-sufficiency by imposing farming on the Sioux, something that was culturally new to them and something they resisted. In addition, drought, grasshoppers, and alkaline soil made it almost impossible for the Indians at Standing Rock to become self-sufficient farmers. The lands authorized by the government were not suitable for farming, while much of the better land was preserved for a time when the reservation would be open to homesteaders. Still, by 1877 at Standing Rock, there was progress toward “civilization” as the government termed it: as buffalo skin tepees wore out, many Indians moved into log cabins. Two Bears and John Grass purchased mowing machines, and Catholic missionaries opened a school for boys and a school for girls. To government officials these outward trappings of American life made them confident the people of Standing Rock were abandoning their traditions.

Provisions for education were contained in treaties and agreements. Many of the Dakota and Lakota people at Standing Rock felt schooling would be beneficial for their children and for the tribe. Indian people understood they would be living in the presence of the white man’s culture and they felt it was important to have children learn English so the people could communicate on an equal basis with the white people. Indian people believed this education would provide their people with new skills and abilities, and did not suspect that education as envisioned by the federal government would seek to erase their Indian languages and traditional values. Government officials supported a system of off-reservation boarding schools for Indians in order to “educate them in the civilization of the white man.” Boarding schools were looked upon as the best way to educate Indian children because they removed the child from the family environment and permitted total immersion in the English language and Euro-American values. Once the Sioux were confined to the Great Sioux Reservation, boarding and day schools sprang up quickly at Standing Rock Agency. Off-reservation boarding schools also sprang up and many young people from Standing Rock were placed at Hampton Institute, a non-sectarian Christian boarding school in Virginia; others went to Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania, a federal school that was the prototype for government-run Indian boarding schools.

All schools, whether local or distant, had the overriding goal of assimilation of Indians into the white man’s ways. Education and farming were keystones of federal policy to assimilate Indians. In the schools the young people learned English, as well as some skills in mathematics, reading, and writing; they spent a good deal of time learning vocational skills such as sewing, making butter, baking, managing a garden, homemaking for the girls and farming, animal husbandry, shoemaking, carpentry, and blacksmithing for the boys. All the schools imposed harsh military discipline on the children, forbade the use of Indian languages, and intentionally forbade any teaching of Native American culture or history. Since the federal government’s plan for Indians was to settle them on individual plots of land and make farmers of them, the education programs emphasized practical skills needed for this life.

Government officials felt rapid progress toward assimilation of Indians would occur with school systems in place. However, at Standing Rock Agency and elsewhere, the Indian people did not readily sacrifice the values, traditions, and language which defined them as a people and gave them strength. For a time after moving onto the reservation, the people continued their spiritual teachings and practices and they held social dances and give-aways. In 1880, the Dakota and Lakota of Standing Rock Agency combined to hold a sun dance and this caused great controversy. Government officials and some military personnel accused the agent of letting his charges sink into barbarism rather than keeping them on the path to civilization.

In 1883 the government issued a set of so-called Indian Offenses that strictly forbade all traditional ceremonies which aimed straight at the center of Dakota and Lakota spiritual life. All traditional lifeways and ceremonies were banned by law. These included give-aways, the sun dance, rites of purification, and social dancing, to name a few. (See Courts of Indian Offenses, Document 2)

Indians were confined to the reservation and needed to have written permission if they left the reservation on business. Parents who kept their children out of school were subject to arrest and to having food rations withheld. In Fort Yates the government-run trading post was divided by a five foot wall—one side for Indians, the other side for whites. Government interference in all facets of Indian life made the Dakota and Lakota of Standing Rock Agency virtual prisoners on their own land, subject to government policy that sought to crush their cultural ways and distinctiveness as a people. Some of the ceremonies continued infrequently and secretly, away from the eyes of the agent. But the stringent laws coupled with removal of children from families for education, and a host of other stresses such as poor health and disease caused a sadness to settle over the people.

Breakup of the Great Sioux Reservation

Sitting Bull, a Hunkpapa, returned to the United States from Canada in 1881. He was held as a prisoner at Fort Randall, Dakota Territory, by the army until he was returned to Standing Rock Agency in June 1883. The Indian Agent at Standing Rock, Major James McLaughlin, disliked Sitting Bull because Sitting Bull openly spoke against government intrusion in Indian life. Sitting Bull never signed a treaty and he always urged his people to maintain their identity as Indian; he advised the Standing Rock people to be open but cautious in their dealings with white people.

“If you see anything good in the white man’s road, pick it up and keep it, but if you find something that is not good, or turns out bad, leave it alone.... (Vestal, New Sources, p. 273)

McLaughlin and other government officials viewed that as tantamount to the complete rejection of “civilization;” there was no room for compromise in government policy. When Sitting Bull first returned to Standing Rock, McLaughlin insisted he live near the agency offices but in time Sitting Bull moved further south and lived along the Grand River in a spot between the present-day communities of Rock Creek (Bullhead) and Little Eagle, in present-day South Dakota. McLaughlin viewed Sitting Bull as a threat to his authority as agency agent.

|

As it became evident that North Dakota and South Dakota would be admitted to the Union, Dakotans insisted on a reduction of the Great Sioux Reservation. These Indian lands blocked more than 43,000 square miles to settlement and economic development, but any attempts to reduce the Sioux land base had been unsuccessful to this point. In 1888 and 1889, federal commissions were sent once more to various Sioux agencies in attempts to get Indian approval of the Sioux Bill which called for the break-up of the Great Sioux Reservation into a smaller reservation, forfeiture of nine million acres of land, allotment of lands to individual families, and opening of non-allotted land to homesteading. The 1888 commission began its work at Standing Rock and then sought signatures of three-quarters of the adult Sioux males, as required by the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty. There was organized opposition to the Sioux Bill at Standing Rock, and it became evident to the government-appointed commissioners that even if other agencies were more receptive, the commission would still lack the necessary signatures for passage. The government retreated and planned new strategy.

In 1889, North Dakota and South Dakota were holding statehood conventions and constituents of the soon-to-be states again demanded reduction of the Great Sioux Reservation. So, government commissioners were once again on the Great Sioux Reservation seeking the break-up of this land base.

The Dakota and Lakota at Standing Rock overwhelmingly opposed the reduction of their reservation. Appointed spokesmen, John Grass, Gall, and Mad Bear spoke eloquently in opposition to the Sioux Bill. However, the commissioners, aided by Agent McLaughlin, applied unrelenting pressure to the Dakota and Lakota of Standing Rock to get their assent to the break-up of the Great Sioux Reservation. Sitting Bull, though not an appointed spokesman, openly opposed the land cession and urged the people not to be intimidated and not to sign away the land.

There was a great deal of Indian opposition to the Sioux Bill and the government officials repeatedly warned the people of Standing Rock that the government would seize the land if the Indians did not sign it away. Great pressure was exerted on the people and after much resistance approximately half of the Standing Rock Sioux males, eighteen years and older, signed assent to the Sioux Bill. Standing Rock was the last agency visited and when these signatures were combined with those at the other agencies, it was enough to cause the break-up of the Great Sioux Reservation into six smaller land areas and resulted in the loss of nine million acres of land. The Sioux Act also set in motion allotment and opening of the reservation to non-Indians. With passage of the Sioux Bill in the United States Congress, Standing Rock Reservation came into being in 1890.

The Ghost Dance

In 1889 the Lakota and Dakota at Standing Rock, and on all the newly defined Sioux reservations, were in poor health, starving, and were witnessing relentless assaults on their tribal way of life. The signing of the Sioux Bill of 1889 accentuated the grievances of the Sioux people and caused sharp division between signers and non-signers. Sitting Bull openly spoke against those who signed the Sioux Bill, and he predicted the government would not honor its promises and those Indians who signed would live to regret giving in. Sitting Bull continued to be the leading opponent of the government’s civilizing policies. Against this backdrop, word of the Ghost Dance was spreading among the Sioux the summer and fall of 1889. The Ghost Dance was a pan-tribal religious movement originating from the vision of a Paiute man in Nevada named Wovoka. The Ghost Dance was basically Christian in its tenets but Indian in ceremonial trappings. The Ghost Dance was not part of spiritual traditions of the Lakota or Dakota, but it had appeal to some Lakota and Dakota people because it promised a return to older traditions and values. Indian people were in terrible straits by 1889 and to some, the Ghost Dance promised many good things. Some Sioux, primarily on the Rosebud, Pine Ridge, Cheyenne River, and Standing Rock Reservations became interested in the Ghost Dance.

|

Wild and unfounded rumors of the Ghost Dance and an impending Sioux outbreak spread to non-Indian communities throughout the Dakotas in the spring of 1890. Fear of the Ghost Dance apparently played into Agent McLaughlin’s hands. Some people in Sitting Bull’s camp participated in the Ghost Dance although Sitting Bull did not take part in it. McLaughlin considered Sitting Bull a malcontent who refused to accept government policy and clung “tenaciously to the old Indian way...slow to accept the better order of things...” So McLaughlin seized on local fear of the Ghost Dance to order the arrest and removal of Sitting Bull from Standing Rock.

The real issue of importance at Standing Rock in the fall of 1890 was not the Ghost Dance but the survey of lands for allotments. Sitting Bull and his followers let it be known they would not take allotments when the time came; they stated they had not signed the Sioux Bill and would therefore “continue to enjoy their old Indian ways.”

In late fall McLaughlin devised a plan to arrest Sitting Bull and by December he was able to implement it. In the pre-dawn hours of December 15, 1890, Indian police from Standing Rock were sent to arrest Sitting Bull and take him to Fort Yates. By daybreak Sitting Bull, eight of his people, and six Indian police lay scattered about Sitting Bull’s camp, dead or dying. Many of those involved in this melee were related, a fact McLaughlin was aware of and commented on.

Sitting Bull’s death caused his people to scatter, and many headed south to relatives on the Cheyenne River Reservation and joined with Hump’s or Spotted Elk’s bands. Some joined relatives living with Big Foot, whose band was attacked on the morning of December 29, 1890, along the Wounded Knee Creek on the Pine Ridge Reservation. Sitting Bull’s death, followed soon by the deaths of almost 300 men, women, and children in the barren gullies and draws of Wounded Knee, was a profound sign that indeed, a new way of life was upon the people.

By 1890 federal policy sought to erase all traces of Indian lifeways. A report from the Commissioner of Indian Affairs clearly sets forth this policy:

The Indians must conform to the “white man’s ways” peaceably if they will, forcibly if they must. They must adjust themselves to their environment, and conform their mode of living substantially to our civilization. This civilization may not be the best possible but it is the best the Indians can get. (BIA Report, 1889)

Allotment

After Sitting Bull’s death and the troubles at Wounded Knee, Standing Rock Indians were dispirited and under strict government control. The people planted small gardens, raised some livestock, and began to settle on small plots of land, though large numbers of official allotments were not made until 1906. As always, farming was problematic on the Great Plains; Standing Rock farmers were challenged by drought, grasshoppers, and poor land. Indian children continued to attend on and off reservation boarding schools. Parents who objected to sending their children to boarding schools were dealt with harshly. Often food was withheld and fathers were jailed until they relented and put their children in school. Children sent to the on-reservation boarding schools were often kept from seeing their parents from September until spring and the children cried a lot for their families. Off-reservation boarding schools were even harsher—children often did not see their families for many years, discipline was strict, and many children at the schools died of homesickness or disease. Captain Pratt, founder of Carlisle Indian School, the federal prototype for Indian schools, stated his philosophy of education:

“We accept the watch word. There is no good Indian but a dead Indian. Let us by education and patient effort kill the Indian and save the man.”

The hope and purpose of this education was to give the Indians skills to become self-sufficient farmers and live on their own allotment of land. When this goal was reached the government would then terminate the reservation system.

Allotment provisions affecting most tribal groups were contained in a federal law, the Dawes Allotment Act of 1887. Special provision for the allotment of Dakota and Lakota lands was also contained in the Sioux Bill of 1889. It was the goal of the federal government to allot 160–320 acre farmsteads to each Indian family, then throw open the reservation to non-Indian settlement dissolving the Indian land base and ending the reservation system. Government officials placed much hope in the allotment of individual plots of land to Indian families. Allotment shaped the education policy and government policy for Indians. The government believed the surest way to bring about the assimilation of Indian people was to make them self-sufficient farmers, much like their non-Indian neighbors. Individual land ownership, an important provision of allotment, would also break up tribalism in which lands were used in common with no sense of ownership. The prevailing wisdom of the day was that Indian people would suddenly drop their values, teachings, language, and cultural practices if they could be moved onto individual plots of land, learned English, and dressed in the fashion of mainstream Americans. However, many Indian families continued to live in large kinship groups, speak the language, and keep alive many of the traditions even after they received their allotment. In fact, agent reports indicated that farming at Standing Rock was done cooperatively by kinship groups and they purchased and used farm equipment cooperatively. Later government policy sought to separate allotments of related families to enforce the concept of individuality among the Standing Rock people. The federal government saved the best, most productive lands for homesteading by non-Indians, and allotted poor, barren lands to the Indians. So, federal practice doomed its own policy.

In many ways, government policy which sought to blend Indians in with the general population only served to bind Indian people together. At Standing Rock, as on so many reservations, the people seemed to follow Sitting Bull’s advice—they chose to accept aspects of the white man’s world but they never gave up those essential values which defined them as Dakota and Lakota. To the Indian people, the reservation is homeland—a place guaranteed and set aside by treaty and agreement for their use and occupancy. Over the years there has been a real struggle to hold onto the land base as well as maintain the culture, lifeways, spiritual traditions, and language. So, even as non-Indians established homesteads and moved within the boundaries of the Standing Rock Reservation, outward changes came about in the lifestyle of the Dakota or Lakota people—now the people lived in log cabins, they wore “citizen’s dress,” and their children attended schools. But high value was still put on maintaining language and through language maintaining those unique qualities that identified the people as Dakota and Lakota—emphasis on generosity and sharing with others, a spiritual attachment to the land, emphasis on strength derived from extended family networks, an overall identity as a people with unique cultural traditions.

Still the federal government relentlessly enforced policies on the reservations aimed at assimilating the people into mainstream society and with the express goal of eventually ending the reservation system. Citizenship for Indians was a major long term goal of the Dawes Allotment Act. Twenty-five years after being assigned an allotment, those families showing “competence” in managing their own affairs were given clear title to the land and citizenship in the U.S. The Department of the Interior devised a “Ritual on Admission of Indians to Full American Citizenship” (See Document 4 & Document 5), in which Indians shot off a last arrow, denounced their Indian ways and pledged to “live the life of the white man” or “white woman.” For those Indian people not yet deemed competent to manage their own affairs, federal agents continued to rule with an iron fist. However, the people of Standing Rock, though under many cultural stresses, continued to organize along more traditional patterns—it was what they knew and for them it was the natural way to do things.

Sioux Claim

At Standing Rock, as well as on the other Sioux reservations, the loss of the Black Hills was a source of great indignation and grief. The Black Hills, referred to as “the heart of everything that is,” were known to the people as a sacred area long before they moved permanently onto the Plains, and their taking through the 1876 Agreement was illegal—nowhere near three-quarters of the adult Sioux males had signed the document. The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 was still enforced. In the 1890s the Sioux began to organize Black Hills Councils on their various reservations. At Standing Rock, the Dakota and Lakota also organized and met to discuss the illegal taking and ways of pressing their claim for return of the Hills. Members of the Black Hills Council lobbied U.S. Congress and sponsored activities to raise money to fund meetings, trips to Washington, and other Black Hills claims expenses.

|

Despite all these pressures and setbacks, the people at Standing Rock and on other Sioux reservations had never lost sight of the Black Hills claim. In 1923 this claim was filed in the U.S. Court of Claims. The tribes gathered data, hired lawyers, and continued to meet and plan strategy in this case which was so important spiritually and culturally for the people. Hopes for a quick resolution on this case were not realized. In addition to the Black Hills Council, in 1914 the people of Standing Rock formed a general council of men to oversee the needs of the people and communicate these to the agent. In fact, that very year, the council complained that white stockmen were ranging cattle on their lands and destroying crops.

Citizenship

When World War I began Indian men from Standing Rock, as well as many other reservations in the United States, enlisted in the armed services even though most were not citizens. Richard Blue Earth of Cannonball was the first North Dakota Indian to enlist. When soldiers returned home their people greeted them as warriors, much as in the old days, and each community honored its men with victory dances and songs. Additionally, Indian communities supported the war efforts by buying bonds and contributing to the Red Cross. In 1919, in appreciation for Indian service in World War I, all Indians who served in the armed forces were granted citizenship. In 1924, all remaining Indians were made citizens of the U.S.

By the 1920s a number of Dakota and Lakota people on Standing Rock were raising cattle or running farm operations, but due to problems with the subdivision of allotments upon death of the original allottee many heirs were forced to lease their small land holdings to local ranchers. By the late 1920s Standing Rock lands were dangerously overgrazed. A severe drought had caused widespread crop failure. Livestock was wiped out and the land was severely eroded. The once lush and bountiful lands of the Plains, after 50 years of federal management, were a barren, desolate, and dusty land. The Great Depression forced some of the Standing Rock people to sell their allotments to survive, and many were again forced to accept rations or die of starvation.

Indian Reorganization

In the 1930s President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, with its public works programs and conservation projects, extended to Indian reservations as it did to all of rural America. For the Sioux of Standing Rock, these programs made possible the survival of the people on the land. Many public works projects were begun on the reservation. Between 1933 and 1936, the Indian Civilian Conservation Corps dug wells, strung fences, planted gardens, constructed roads, and established a community ranching program. However, the Bureau of Indian Affairs controlled the sales and many families lost money since the cattle were sold below market value. During this time a mood of political reform was sweeping across the U.S. and this impacted Indian country. Commissioner of Indian Affairs, John Collier, proposed altering the way the U.S. government did business with the tribes through the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of 1934. Among other things, Collier proposed formal recognition of the tribal councils that existed on reservations and more tribal input into federal decision-making that affected Indian people. Tribes had the choice to reorganize under a constitutional form of government which, at least in theory, gave the tribes greater autonomy. Unfortunately, most of the IRA constitutions were written in Washington and were presented to the people for approval or disapproval with little or no local input. The IRA constitutions more often mimicked county forms of government rather than reflecting traditional Indian governance. In the IRA constitutions, majority rule would replace consensus which is the way the Dakota and Lakota made decisions, and the Bureau of Indian Affairs reserved the right to approve or disapprove all decisions made by the tribal councils. Reservations were economically depressed and desperately needed funds for land consolidation and economic development, and so as a way to make re-organization under the IRA attractive, those tribes that accepted the IRA were eligible for revolving loans.

The members of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe were mistrustful of provisions in the IRA that gave the Secretary of the Interior authority over certain areas of tribal affairs.

Learning that the IRA would limit the tribe’s sovereignty, Standing Rock people did not choose to reorganize under the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934. In 1914 the tribal council adopted a constitutional form of government and even without accepting the IRA, this council would have more authority to make decisions on a local level. Over time, the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe revised its constitution. Today the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe is governed by a tribal council elected from eight districts on the reservation.

In 1948, the Army Corps of Engineers began construction of the Oahe Dam. Despite intense opposition from the Standing Rock Sioux Tribal Council, 160,889 acres of prime agricultural and rangelands were flooded, and 25 percent of the reservation populace was forced to move to other parts of the reservation. The impact on the reservation has been significant both in economic and psychological terms.

acres of the Standing Rock Reservation was permanently flooded. (SHSND-ND Studies)

With the passage of Public Law 93-638, the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act, tribal governments were permitted by the federal government to assume greater control in managing the affairs on their reservations and the Bureau of Indian Affairs assumed a more advisory role. With the Self-Determination Act, tribes could contract to operate programs and services previously run by the BIA. At Standing Rock the tribe has assumed control over a variety of programs including areas of social services, higher education, and land management programs.

The Standing Rock Sioux tribe seeks to gradually assume management of most reservation programs, including reservation schools. The tribe also looks toward greater economic development on the reservation. Tribal programs that reflect local needs and concerns insure programs will not conflict with tribal cultural values of the Dakota and Lakota people as was so predominant in the past when the federal government ran the reservation.