Sioux Pictograph

Sioux Pictograph of the Whitestone Hill Battle

About 50 years after the battle at Whitestone Hill, an Indian pictograph of the battle was drawn by Richard Cottonwood, as directed by Takes-His-Shield—who was apparently at Whitestone Hill in 1863. The pictograph presents the Sioux Indian tradition of the conflict at Whitestone Hill. The following explanation of the pictograph, or “Map-History,” is summarized from an interpretation written by Rev. Aaron McGaffey Beede in 1932, almost 20 years after the pictograph was drawn. Beede served as an Episcopal missionary among the Sioux at Fort Yates in North Dakota for many years.

The photo is from the State Historical Society of North Dakota.

The explanation begins near the number “1” on the pictograph, beside the circle of tipis. The many Sioux heads show that Indian men, women, and children were at the camp. They were on their autumn buffalo hunt and frying meat for the winter, as indicted by the jerked meat hanging from poles supported by forked posts near the tipis. The camp was in the broken prairie country beside a small lake. The lake is shown, along with lines indicating hill ridges and a sort of squarish table land.

The camp consisted of two groups of Sioux, one accustomed to war and to spears, and the other using only arrows. War scalps are drawn on the tops of the tipi poles of some tipis and these tipis are shown with spears, while other tipi poles have no scalps and are shown with arrows. The two groups of Sioux were so friendly that they are all shown camped in one circle, not in two circles.

A large army of mounted white soldiers suddenly swooped down upon the Sioux, with the horse tracks of white soldiers shown in an orderly array or pattern. The soldier’s attack is shown coming from the lower right corner of the map. Most of the Indians started to run away, fleeing in the direction opposite the army. A fleeing woman has hitched a travois to a horse which has no rider, and three children are crowded onto this travois.

Now the perspective changes on the pictograph to the opposite corner labeled with number “2.” An Indian reading this large pictograph on the floor would typically walk around the map to the opposite corner.

A small lake or hilly rise is shown near the “2.” A large part of the army is rushing, shown by hoof prints in well-formed order, to encircle the fleeing Indians and cut off their escape. A smaller number of soldiers pursue the fleeing Indians without killing any of them. An Indian woman catches a get-away horse, places an old woman in the saddle, and hitches her travois loaded with children to the horse. No one has been killed yet.

A column of troops turns down near the outside of the “2,” chasing Indians who had gone that way. Another woman with a get-away horse, together with many other Indians, swings by a circular route back toward the “1.” So far none has been killed, and these Indians have not put up a fight or any type of defense.

Now the viewpoint changes to the number “3” area. The troopers have the Indians between them and are killing the Indians, but the Indians are not fighting: not one arrow is in the picture. The mark that looks something like “R” on the face means the person was killed, and the fact that 25 or 30 of these marks are present in this part of the pictograph indicates a slaughter of the Indians.

Now the story moves to the number “4” area of the map. After killing the Indians, a large number of soldiers went away, with their horse tracks crossing the ones made earlier. Some of the Indians escaped at this time, indicated by the faces with no marks showing that they were killed. Then darkness came, so that no eyes actually saw where the troopers went or where the Indians escaped. The only events shown in the picture are those that could be seen, and what happened after darkness set in could not be seen. No Indians had fired arrows or fought the soldiers in any way, according to the pictograph.

Beede also wrote that he had once asked Takes-His-Shield why he was not in the map, as is usually the case with the Indian who makes the pictograph. According to Beede, Takes-His-Shield “said that since that time he had been in the other life ...the same as dead, and so he must not put himself into it. There was a slight tremble in his voice, but otherwise no emotion, firm set face and jaws.... He was a man of few words and seldom talked with people abut the matter.”

“It should be noted that as a historical source, this depiction of the Whitestone Hill conflict is only as accurate as the memory of one participant a half century after the event occurred, plus the still later interpretation by someone who was not there at all. The pictograph is valuable, however, because it does present the Indian tradition of the engagement.” (Beede, pp. 97–98) Interpretation from Shimmin-Tveit Museum, Forbes, North Dakota)

“It should be noted that as a historical source, this depiction of the Whitestone Hill conflict is only as accurate as the memory of one participant a half century after the event occurred, plus the still later interpretation by someone who was not there at all. The pictograph is valuable, however, because it does present the Indian tradition of the engagement.” (Beede, pp. 97–98) Interpretation from Shimmin-Tveit Museum, Forbes, North Dakota)

Courts

97. Courts of Indian Offenses

Extract from the Annual Report of the Secretary of the Interior November 1, 1883

Secretary of the Interior Henry M. Teller instigated the establishment on Indian reservations of so-called courts of Indian offenses. His goal was to eliminate “heathenish practices” among the Indians, but the courts came to be general tribunals for handling minor offenses on the reservations. His directions to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs in regard to the courts were given in his annual report of 1883.

....Many of the agencies are without law of any kind, and the necessity for some rule of government on the reservations grows more and more apparent each day. If it is the purpose of the government to civilize the Indians, they must be compelled to desist from the savage and barbarous practices that are calculated to continue them in savagery, no matter what exterior influences are brought to bear on them. Very many of the progressive Indians have become fully alive to the pernicious influences of these heathenish practices indulged in by their people, and have sought to abolish them; in such efforts they have been aided by their missionaries, teachers, and agents, but this has been found impossible even with the aide thus given. The Government furnishes the teachers, and the charitable people contribute to the support of missionaries, and pended by their elevation, and yet a few non-progressive, degraded Indians are allowed to exhibit before the young and susceptible children all the debauchery, diabolism, a savagery of the worst state of the Indian race. Every man familiar with Indian life will bear witness to the pernicious influence of these savage rites and heathenish customs.

On the 2nd of December last, with the view of as soon as possible putting an end to these heathenish practices, I addressed a letter to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs which I here quote as expressive of my ideas on this subject:

I desire to call your attention to what I regard as a great hindrance to the civilization of the Indians, viz, the continuance of the old heathenish dances, such as the sun-dance, scalp-dance, etc. These dances, or feasts, as they are sometimes called, ought, in my judgment, to be discontinued, and if the Indians now supported by the Government are not willing to discontinue them, the agents should be instructed to compel such discontinuance. These feasts or dances are not social gatherings for the amusement of these people, but, on the contrary, are intended and calculated to stimulate the warlike passions of the young warriors of the tribe. At such feasts the warrior recounts his deeds of daring, boasts of his inhumanity in the destruction of his enemies, and his treatment of the female captives, in language that ought to shock even a savage ear. The audience assents approvingly to his boasts of falsehood, deceit, theft, murder, and rape, and the young listener is informed that this and this only is the road to fame and renown. The result is the demoralization of the young, who are incited to emulate the wicked conduct of their elders, without a thought that in so doing they violate any law, but on the contrary, with the conviction that in so doing they are securing for themselves an enduring and deserved fame among their people. Active measures should be taken to discourage all feasts an dances of the character I have mentioned.

The marriage relation is also one requiring the immediate attention of the agents. While the Indians were in a state of at least semi-independence, there did not seem to be any great necessity for interference, even if such interference was practicable (which doubtless was not). While dependent on the chase the Indian did not take many wives, and the great mass found themselves too poor to support more than one; but since the Government supports them this objection no longer exists, and the more numerous the family the greater the number of the rations allowed. I would not advise any interference with plural marriages now existing; but I would by all possible methods discourage further marriages of that character. The marriage relation, if it may be said to exist at all among the Indians, is exceedingly lax in its character, and it will be found impossible, for some time yet, to impress them with our idea of this important relation.

The marriage state, existing only by the consent of both parties, is easily and readily dissolved, the man not recognizing any obligations on his part to care for his offspring. As afar as practicable, the Indian having taken of himself a wife should be compelled to continue that relations with her, unless dissolved by some recognized tribunal on the reservation or by the courts. Some system of marriage should be adopted, and the Indian compelled to conform to it. The Indian should also be instructed that he is under obligations to care for and support, not only his wife, but his children, and on his failure, without proper cause, to continue as the head of such family, he ought in some manner to be punished, which should be either by confinement in the guard-house or agency prison, or by a reduction of his rations.

Another great hindrance to the civilization of the Indians is the influence of the medicine men, who are always found with the anti-progressive party. The medicine men resort to various artifices and devices to keep the people under their influence, and are especially active in preventing schools, using their conjurers’ arts to prevent the people from abandoning their heathenish rites and customs. While they profess to cure diseases by the administering of a few simple remedies, still they rely mainly on their art of conjuring. Their services are not required even for the administration of the few simple remedies they are competent to recommend, for the Government supplies the several agencies with skillful physicians, who practice among the Indians without charge to them. Steps should be taken to compel these imposters to abandon this deception and discontinue their practices, which are not only without benefit to the Indians but positively injurious to them.

A young Dakota named Frosted was imprisoned at

Fort Yates military post for practicing his

traditional religion—he went on a hill, fasted, and made a prediction

to his people. At all Indian agencies the practice of any

Indian spiritual traditions was considered an offense that

could land one in jail. Notice the ball and chain.

SHSND

The value of property as an agent of civilization ought not to be overlooked. When an Indian acquires property, with a disposition to retain the same free from tribal or individual interference, he has made a step forward in the road to civilization. One great obstacle to the acquirement of property by the Indian is the very general custom of destroying or distributing his property on the death of a member of his family. Frequently on the death of an important member of the family, all the property accumulated by its head is destroyed or carried off by the “mourners,” and his family left in isolation and want. While in their independent state but little inconvenience was felt in such a case, on account of the general community of interest and property, in their present condition not only real inconvenience is felt, but disastrous consequences follow. I am informed by reliable authority that frequently the head of a family finding himself thus despoiled of his property, becomes discouraged, and makes no further attempt to become a property owner. Fear of being considered mean and attachment to the dead, frequently prevents the owner from interfering to save his property while it is being destroyed in the presence and contrary to his wishes.

It will be extremely difficult to accomplish much towards the civilization of the Indians while these adverse influences are allowed to exist.

The Government having attempted to support the Indians until such time as they shall become self-supporting, the interest of the Government as well as that of the Indians demands that every possible effort should be made to induce them to become self-supporting at as early a day as possible. I therefore suggest whether it is not practicable to formulate certain rules for the government of the Indians on the reservations that shall restrict and ultimately abolish the practices I have mentioned. I am not ignorant of the difficulties that will be encountered in this effort; yet I believe in all the tribes there will be found many Indians who will aid the government in its efforts to abolish rites and customs so injurious to the Indians and so contrary to the civilization that they earnestly desire.

In accordance with the suggestions of this letter, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs established a tribunal at all agencies, except among the civilized Indians, consisting of three Indians, to be known as the court of Indian offenses. The members of this tribunal consist of the first three officers in rank of the police force, if such selection is approved by the agent; otherwise, the agent may select from among the members of the tribe three suitable persons to constitute such tribunal.

The Commissioner of Indian Affairs, with the approval of the Secretary of the Interior, promulgated certain rules for the government of this tribunal, defining offenses of which it was to take cognizance. It is believed that such a tribunal, composed as it is of Indians, will not be objectionable to the Indians and will be a step in the direction of bringing the Indians under the civilizing influence of law. Since the creation of this tribunal the time has not been sufficient to give it a fair trial, but so far it promises to accomplish all that was hoped for at the time of its creation. The Commissioner recommends an appropriation for the support of this tribunal, and in such recommendation I concur. … [House Executive Document no. 1, 48th Congress, 1st Sess., serial 2190, PP. x-xiii]

98. Ex Parte Crow Dog

When the Brulé Sioux chief Crow Dog was sentenced to death by the First Judicial District Court of Dakota for the murder of Spotted Tail, he brought suit for release on the grounds that the federal courts had no jurisdiction over crimes committed in the Indian country by one Indian against another. The Supreme Court upheld his petition and released him.

...The petitioner is in the custody of the marshal of the United States for the Territory of Dakota, imprisoned in the jail of Lawrence County, in the First Judicial District of that Territory, under sentence of death, adjudged against him by the district court for that district, to be carried into execution January 14, 1884. That judgment was rendered upon a conviction for the murder of an Indian of the Brulé Sioux band of the Sioux Nation of Indians, by the name of Sin-ta-ge-le-Scka, or in English, Spotted Tail, the prisoner also being an Indian, of the same band and nation, and the homicide having occurred as alleged in the indictment, in the Indian country, within a place and district of country under the exclusive jurisdiction of the United States and within the said judicial district. The judgment was affirmed, on a write of error, by the Supreme Court of the Territory. It is claimed on behalf of the prisoner that the crime charged against him, and of which he stands convicted, is not an offence under the laws of the United States; that the district court had no jurisdiction to try him, and that its judgment and sentence are void. He therefore prays far a writ of habeas corpus, that he may be delivered from an imprisonment which he asserts to be illegal...

It must be remembered that the question before us is whether the express letter of §2146 of the Revised Statutes, which excludes from the jurisdiction of the United States the case of a crime committed in the Indian country by one Indian against the person or property of another Indian, has been repealed. If not, it is in force and applies to the present case. The treaty of 1868 and the agreement and act of Congress of 1877, it is admitted, do not repeal it by any express words. What we have said is sufficient at least to show that they do not work a repeal by necessary implication...

...It is a case involving the judgment of a court of special and limited jurisdiction, not to be assumed without clear warrant of law. It is a case of life and death. It is a case where, against an express exception in the law itself, that law, by argument and inference only, is sought to be extended over aliens and strangers; over the members of a community separated by race, by tradition, by the instincts of a free though savage life, from the authority and power which seeks to impose upon them the restraints of an external and unknown code, and to subject them to the responsibilities of civil conduct, according to rules and penalties of which they could have no previous warning; which judges them by a standard made by others and not for them, which takes no account of the conditions which should except them from its exactions, and makes no allowance for their inability to understand it. It tries them, not by their peers, nor by the customs of their people, nor the law of their land, but by superiors of a different race, according to the law of a social state of which they have an imperfect conception, and which is opposed to the traditions of their history, to the habits of their lives, to the strongest prejudices of their savage nature; one which measures the red man’s revenge by the maxims of the white man’s morality.

Language

27 J.D.C. Atkins/The English Language in Indian Schools

Great emphasis was placed upon the use of the English language in schools attended by Indian children. One of the strongest advocates of the policy was J.D.C. Atkins, Commissioner of Indian Affairs from 1885 to 1888. His directives to agents and to superintendents of Indian schools reflected his belief that the Indian vernacular had to be replaced entirely by English. In his report to the Secretary of the Interior in 1887, Atkins gives a brief history of the movement for English in the Indian schools and his arguments in favor of that policy. He supplies as well testimonials from other reformers in support of his position.

In the report of this office for 1885 incidental allusion was made to the importance of teaching Indians the English language, the paragraph being as follows:

“A wider and better knowledge of the English language among them is essential to their comprehension of the duties and obligations of citizenship. At this time but few of the adult population can speak a word of English, but with the efforts now being made by the Government and by religious and philanthropic associations and individuals, especially in the Eastern States, with the missionary and the schoolmaster industriously in the field everywhere among the tribes, it is to be hoped, and it is confidently believed, that among the next generation of Indians the English language will be sufficiently spoken and used to enable them to become acquainted with the laws, customs, and institutions of our country.”

From Report of September 21, 1887, in House Executive Document No. 1, part 5, vol. 11, 50 Congress, 1 session, serial 2542, pp. 18–23.

The idea is not a new one. As far back as 1868 the commission known as the “Peace Commission,” composed of Generals Sherman, Harney, Sanborn, and Terry, and Messrs. Taylor (then Commissioner of Indian Affairs), Henderson, Tappan, and Augur, embodied in the report of their investigations into the condition of Indian tribes their matured and pronounced views on this subject, from which I make the following extracts:

“The white and Indian must mingle together and jointly occupy the country, or one of them must abandon it. ... What prevented their living together? … Third. The difference in language, which in a great measure barred intercourse and a proper understanding each of the other’s motives and intentions. Now, by educating the children of these tribes in the English language these differences would have disappeared, and civilization would have followed at once. Nothing then would have been left but the antipathy of race, and that, too, is always softened in the beams of a higher civilization. ... Through sameness of language is produced sameness of sentiment, and thought; customs and habits are molded and assimilated in the same way, and thus in progress of time the differences producing trouble would have been gradually obliterated. By civilizing one tribe others would have followed. Indians of different tribes associate with each other on terms of equality; they have not the Bible, but their religion, which we call superstition, teaches them that the Great Spirit made us all. In the difference of language today lies two-thirds of our trouble. . . . Schools should be established, which children should be required to attend; their barbarous dialect should be blotted out and the English language substituted. … The object of greatest solicitude should be to break down the prejudices of tribe among the Indians; to blot out the boundary lines which divide them into distinct nations, and fuse them into one homogeneous mass. Uniformity of language will do this—nothing else will.”

In the regulations of the Indian Bureau issued by the Indian Office in 1880, for the guidance of Indian agents, occurs this paragraph:

“All instruction must be in English, except in so far as the native language of the pupils shall be a necessary medium for conveying the knowledge of English, and the conversation of and communications between the pupils and with the teacher must be, as far as practicable, in English.”

In 1884 the following order was issued by the Department to the office, being called out by the report that in one of the schools instruction was being given in both Dakota and English:

“You will please inform the authorities of this school that the English language only must be taught the Indian youth placed there for educational and industrial training at the expense of the Government. If Dakota or any other language is taught such children, they will be taken away and their support by the Government will be withdrawn from the school.”

In my report for 1886 I reiterated the thought of my previous report, and clearly outlining my attitude and policy I said:

“In my first report I expressed very decidedly the idea that Indians should be taught the English language only. From that position I believe, so far as I am advised, there is no dissent either among the lawmakers or the executive agents who are selected under the law to do the work. There is not an Indian pupil whose tuition and maintenance is paid for by the United States Government who is permitted to study any other language than our own vernacular—the language of the greatest, most powerful, and enterprising nationalities beneath the sun. The English language as taught in America is good enough for all her people of all races.

“Longer and closer consideration of the subject has only deepened my conviction that it is a matter not only of importance, but of necessity that the Indians acquire the English language as rapidly as possible. The Government has entered upon the great work of educating and ‘citizenizing’ the Indians and establishing them upon homesteads. The adults are expected to assume the role of citizens, and of course the rising generation will be expected and required more nearly to fill the measure of citizenship, and the main purpose of educating them is to enable them to read, write, and speak the English language and to transact business with English-speaking people. When they take upon themselves the responsibilities and privileges of citizenship their vernacular will be of no advantage. Only through the medium of the English tongue can they acquire a knowledge of the Constitution of the country and their rights and duties thereunder.

Every nation is jealous of its own language, and no nation ought to be more so than ours, which approaches nearer than any other nationality to the perfect protection of its people. True Americans all feel that the Constitution, laws, and institutions of the United States, in their adaptation to the wants and requirements of man, are superior to those of any other country; and they should understand that by the spread of the English language will these laws and institutions be more firmly established and widely disseminated. Nothing so surely and perfectly stamps upon an individual a national characteristic as language. So manifest and important is this that nations the world over, in both ancient and modern times, have ever imposed the strictest requirements upon their public schools as to the teaching of the national tongue. Only English has been allowed to be taught in the public school in the territory acquired by this country from Spain, Mexico, and Russia, although the native populations spoke another tongue. All are familiar with the recent prohibitory order of the German Empire forbidding the teaching of the French language in either public or private schools in Alsace and Lorraine. Although the population is almost universally opposed to German rule, they are firmly held to German political allegiance by the military hand of the Iron Chancellor. If the Indians were in Germany or France or any other civilized country, they should be instructed in the language there used. As they are in an English-speaking country, they must be taught the language which they must use in transacting business with the people of this country. No unity or community of feeling can be established among different peoples unless they are brought to speak the same language, and thus become imbued with like ideas of duty.

Deeming it for the very best interest of the Indian, both as an individual and as an embryo citizen, to have this policy strictly enforced among the various schools on Indian reservations, orders have been issued accordingly to Indian agents, and the text of the orders and of some explanations made thereof are given below:

December 14, 1886.

In all schools conducted by missionary organizations it is required that all instructions shall be given in the English language.

February 2, 1887.

In reply I have to advise you that the rule applies to all schools on Indian reservations, whether they be Government or mission schools. The instruction of the Indians in the vernacular is not only of no use to them, but is detrimental to the cause of their education and civilization, and no school will permitted on the reservation in which the English language is not exclusively taught.

July 16, 1887.

Your attention is called to the regulation of this office which forbids instruction in schools in any Indian language. This rule applies to all schools on an Indian reservation, whether Government or mission schools. The education of Indians in the vernacular is not only of no use to them, but is detrimental to their education and civilization.

You are instructed to see that this rule is rigidly enforced in all schools upon the reservation under your charge.

No mission school will be allowed upon the reservation which does not comply with the regulation.

The following was sent to representatives of all societies having contracts with this bureau for the conduct of Indian schools:

Your attention is called to the provisions of the contracts for educating Indian pupils, which provided that the schools shall “teach the ordinary branches of an English education.” This provision must be faithfully adhered to, and no books in any Indian language must be used or instruction given in that language to Indian pupils in any school where this office has entered into contract for the education of Indians. The same rule prevails in all Government Indian schools and will be strictly enforced in all contract and other Indian schools.

The instruction of Indians in the vernacular is not only of no use to them, but is detrimental to the cause of their education and civilization, and it will not be permitted in any Indian school over which the Government has any control, or in which it has any interest whatever.

This circular has been sent to all parties who have contracted to educate Indian pupils during the present fiscal year.

You will see that this regulation is rigidly enforced in the schools under your direction where Indians are placed under contract.

I have given the text of these orders in detail because various misrepresentations and complaints in regard to them have been made, and various misunderstandings seem to have arisen. They do not, as has been urged, touch the question of the preaching of the Gospel in the churches nor in any wise hamper or hinder the efforts of missionaries to bring the various tribes to a knowledge of the Christian religion. Preaching of the Gospel to Indians in the vernacular is, of course, not prohibited. In fact, the question of the effect of this policy upon any missionary body was not considered. All the office insists upon is that in the schools established for the rising generation of Indians shall be taught the language of the Republic of which they are to become citizens.

It is believed that if any Indian vernacular is allowed to be taught by the missionaries in schools on Indian reservations, it will prejudice the youthful pupil as well as his untutored and uncivilized or semi-civilized parent against the English language, and, to some extent at least, against Government schools in which the English language exclusively has always been taught. To teach Indian school children their native tongue is practically to exclude English, and to prevent them from acquiring it. This language, which is good enough for a white man and a black man, ought to be good enough for the red man. It is also believed that teaching an Indian youth in his own barbarous dialect is a positive detriment to him. The first step to be taken toward civilization, toward teaching the Indians the mischief and folly of continuing in their barbarous practices, is to teach them the English language. The impracticability, if not impossibility, of civilizing the Indians of this country in any other tongue than our own would seem to be obvious, especially in view of the fact that the number of Indian vernaculars is even greater than the number of tribes. Bands of the same tribes inhabiting different localities have different dialects, and sometimes can not communicate with each other except by the sign language. If we expect to infuse into the rising generation the leaven of American citizenship, we must remove the stumbling blocks of hereditary customs and manners, and of this language is one of the most important elements.

I am pleased to note that the five civilized tribes have taken the same view of the matter and that in their own schools—managed by the respective tribes and supported by tribal funds—English alone is taught.

But it has been suggested that this order, being mandatory, gives a cruel blow to the sacred rights of the Indians. Is it cruelty to the Indian to force him to give up his scalping-knife and tomahawk? Is it cruelty to force him to abandon the vicious and barbarous sun dance, where he lacerates his flesh, and dances and tortures himself even unto death? Is it cruel to the Indian to force him to have his daughters educated and married under the laws of the land, instead of selling them at a tender age for a stipulated price into concubinage to gratify the brutal lusts of ignorance and barbarism?

Having been governed in my action solely by what I believed to be the real interests of the Indians, I have been gratified to receive from eminent educators and missionaries the strongest assurance of their hearty and full concurrence in the propriety and necessity of the order. Two of them I take the liberty to append herewith. The first is from a former missionary among the Sioux; the second from an Indian agent of long experience, who has been exceedingly active in pushing the educational interests of his Indians.

As I understand it, your policy is to have the Indian taught English instead of his mother tongue. I am glad you have had the courage to take this step, and I hope you may find that support which the justice and rightness of the step deserve. Before you came to administer the affairs of the country the Republicans thought well to undertake similar work in the Government schools, but lacked the courage to touch the work of the mission schools where it was needed. If the wisdom of such work was recognized in the Government school, why not recognize the wisdom of making it general? When l was in Dakota as a missionary among the Sioux, I, was much impressed with the grave injustice done the Indian in all matters of trade, because he could not speak the language in which the trade was transacted. This step will help him out of the difficulty and lift him a long way nearer equality with the white man.

Seeing there is now being considerable said in the public press about the Indian Office prohibiting the teaching of the vernacular to the Indians in Indian schools, and having been connected with the Indian service for the past sixteen years, eleven years of which I have been Indian agent and had schools under my charge, l desire to state that I am a strong advocate of instruction to Indians in the English language only, as being able to read and write in the vernacular of the tribe is but little use to them. Nothing can be gained by teaching Indians to read and write in the vernacular, as their literature is limited and much valuable time would be lost in attempting it. Furthermore, I have found the vernacular of the Sioux very misleading, while a full knowledge of the English enables the Indians to transact business as individuals and to think and act for themselves independently of each other.

As I understand it, the order applies to children of school-going ages (from six to sixteen years) only, and that missionaries are at liberty to use the vernacular in religious instructions. This is essential in explaining the precepts of the Christian religion to adult Indians who do not understand English.

In my opinion school conducted in the vernacular are detrimental to civilization. They encourage Indians to adhere to their time-honored customs and inherent superstitions which the Government has in every way sought to overcome, and which can only be accomplished by adopting uniform rules requiring instruction in the English language exclusively.

I also append an extract on this subject from one of the leading religious weeklies:

English is the language overwhelmingly spoken by our sixty millions of people. Outside of these, there are two hundred thousand Indians old enough to talk who use a hundred dialects, many of which are as unintelligible to those speaking the other dialects as Sanscrit is to the average New England schoolboy. Why, then, should instruction in these dialects be continued to the youth? Why, indeed? They are now in the teachable age; if they are ever to learn English they must learn it now—not when they have become men with families, knowing no other tongue than their own dialect, with its very limited resources, a dialect wholly unadapted to the newer life for which they are being prepared. And they must learn English. The Indians of Fenimore Cooper’s time lived in a terra incognita of their own. Now all is changed; every Indian reservation in the country is surrounded by white settlements, and the red man is brought into direct contact and into conflict with the roughest elements of country life. It is clear, therefore, the quarter of a million of red men on this continent can be left to themselves no longer...

There are pretty nearly ten thousand Indian boys and girls who avail themselves of educational privileges. We want to keep right along in this direction; and how can we do so but by beginning with the youth and instructing them in the language by using which alone they can be qualified for the duties of American citizenship? . . . If the Indian is always to be a tribal Indian and a foreigner, by all means see to it that he learns his own tongue, and no other. But if he is to be fitted for American citizenship how shall he be better fitted than by instructing him from his youth in the language of his real country—the English tongue as spoken by Americans.

As events progress, the Indians will gradually cease to be enclosed in reservations; they will mingle with the whites. The facilities of travel are being as greatly extended by rail, by improved roads and increasing districts of settlement that this intercourse between whites and Indians must greatly increase in future—but how shall the Indian profit by it if he is ignorant of the English tongue? It is said that missionaries can not instruct at all in the Dakota tongue. We do not so understand it. On the whole, when sober reflection shall have been given to the subject, we think many who have assailed the Indian Bureau for its recent order will see and will acknowledge that the action taken by the Interior Department is wise, and that it is absolutely necessary if the Indian is ever to be fitted for the high duties of American citizenship. (Prucha, Documents of United States Indian Policy, 1975. pp, 169–17.)

Citizenship

Ritual on Admission of Indians to Full American Citizenship

Representative of Department Speaking:

The President of the United States has sent me to speak a solemn and serious word to you, a word that means more to some of you than any other that you have ever heard. He has been told that there are some among you who should no longer be controlled by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, but should be given their patents in fee and thus become free American citizens. It is his decision that this shall be done, and that those so honored by the people of the United States shall have the meaning of this new and great privilege pointed out by symbol and by word, so that no man or woman shall not know its meaning. The President has sent me papers naming those men and women and l shall call out their names one by one, and they will come before me.

| For Men: |

|

(Read Name.) _________________ (white name). What was your Indian name? (Gives name.) _________________ (Indian name). I hand you a bow and an arrow. Take this bow and shoot the arrow. (He shoots.) _________________ (Indian name). You have shot your last arrow. That means that you are no longer to live the life of an Indian. You are from this day forward to live the life of the white man. But you may keep that arrow, it will be to you a symbol of your noble race and of the pride you feel that you come from the first of all Americans. _________________ (white name). Take in your hand this plow. (He takes the handles of the plow.) This act means that you have chosen to live the life of the white man—and the white man lives by work. From the earth we all must get our living and the earth will not yield unless man pours upon it the sweat of his brow. Only by work do we gain a right to the land on to the enjoyment of life. _________________ (white name). I give you a purse. This purse will always say to you that the money you gain from your labor must be wisely kept. The wise man saves his money so that when the sun does not smile and the grass does not grow, he will not starve. I give into your hands the flag of your county. This is the only flag you have ever had or ever will have. It is the flag of freedom; the flag of free men, the flag of a hundred million free men and women of whom you are now one. That flag has a request to make of you, _________________ (white name), that you take it into your hands and repeat these words: “For as much as the President has said that I am worthy to be a citizen of the United States, I now promise to this flag that I will give my hands, my head, and my heart to the doing of all that will make me a true American citizen.” And now beneath this flag I place upon your breast the emblem of your citizenship. Wear this badge of honor always; and may the eagle that is on it never see you do aught of which the flag will not be proud. (The audience rises and shouts: “_________________(white name) is an American citizen.”) |

| For Women: |

|

_________________ (white name). Take in your hand this work bag and purse. (She takes the work bag and purse.) This means that you have chosen the life of the white woman—and the white woman loves her home. The family and the home are the foundation of our civilization. Upon the character and industry of the mother and homemaker largely depends the future of our Nation. The purse will always say to you that the money you gain from your labor must be wisely kept. The wise woman saves her money, so that when the sun does not smile and the grass does not grow, she and her children will not starve. I give into your hands the flag of your country. This is the only flag you have ever had or ever will have. It is the flag of freedom, the flag of free men, a hundred million free men and women of whom you are now one. That flag has a request to make of you, _________________ (white name), that you take it into your hands and repeat these words: “For as much as the President has said that I am worthy to be a citizen of the United States, I now promise to this flag that I will give my hands, my head, and my heart to the doing of all that will make me a true American citizen.” And now beneath this flag I place upon your breast the emblem of your citizenship. Wear this badge of honor always, and may the eagle that is on it never see you do aught of which the flag will not be proud. (The audience rises and shouts: “_________________(white name) is an American citizen.”) |

Music

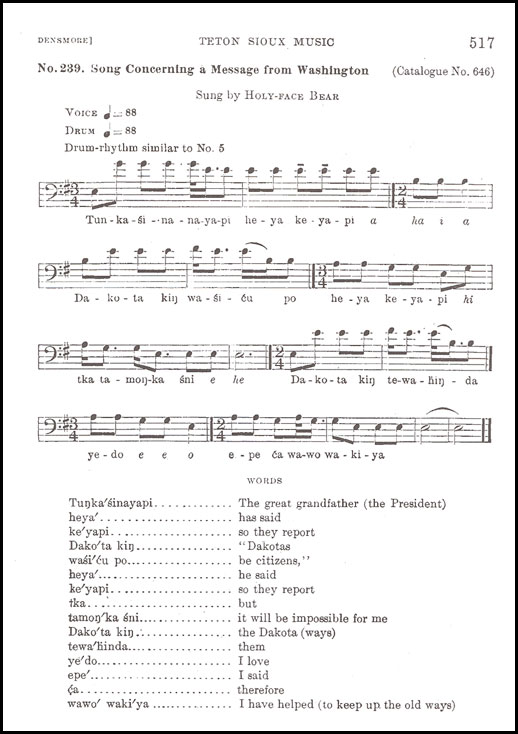

Teton Sioux Music

This song, composed at Standing Rock, demonstrates the wariness the people felt about becoming citizens. The song clearly shows the great value placed on the Dakota culture and traditions. COL-22H59

Analysis. —This song is remarkable in its opening interval, which was uniformly given in three renditions, the fourth rendition beginning on the last part of the first measure. The song is melodic in structure, had a range of 10 tones, and lacks the sixth and seventh tones of the complete octave. This song was said to have been recently composed.

4840˚—Bull. 61–18—35

Treaty 1851

| Articles of a treaty made and concluded at Fort Laramie, in the Indian Territory, between D.D. Mitchell, superintendent of Indian affairs and Thomas Fitzpatrick, Indian agent, commissioners specially appointed and authorized by the President of the United States, of the first part, and the chiefs, headmen, and braves of the following Indian nations, residing south of the Missouri River, east of the Rocky Mountains, and north of the lines of Texas and New Mexico, viz, the Sioux or Dahcotahs, Cheyennes, Arrapahoes, Crows, Assinaboines, Gros-Ventre Mandans, and Arrickaras, parties of the second part, on the seventeenth day of September, A.D. one thousand eight hundred and fifty-one. | Sept. 17, 1851. 11 Stats., p. 749. |

| Article 1 | |

| The aforesaid nations, parties to this treaty, having assembled for the purpose of establishing and confirming peaceful relations amongst themselves, do hereby covenant and agree to abstain in future from all hostilities whatever against each other, to maintain good faith and friendship in all their mutual intercourse, and to make an effective and lasting peace. | Peace to be observed. |

| Article 2 | |

| The aforesaid nations do hereby recognize the right of the United States Government to establish roads, military and other posts, within their respective territories. | Roads may be established. |

| Article 3 | |

| In consideration of the rights and privileges acknowledged in the preceding article, the United States bind themselves to protect the aforesaid Indian nations against the commission of all depredations by the people of the said United States, after the ratification of the treaty. | Indians to be protected. |

| Article 4 | |

| The aforesaid Indian nations do hereby agree and bind themselves to make restitution or satisfaction for any wrongs committed, after the ratification of this treaty, by any band satisfied or individual of their people, on the people of the Unites States, whilst lawfully residing in or passing through their respective territories. | Depredations on whites to be satisfied. |

| Article 5 | |

| The aforesaid Indian nations do hereby recognize and acknowledge the following tracts of country, included within the metes and boundaries hereinafter designated, as their respective territories, viz: | Boundaries of lands. |

| The territory of the Sioux or Dahcotah Nation, commencing the mouth of the White Earth River, on the Missouri River; thence in a southwesterly direction to the forks of the Platte River; thence up the north fork of the Platte River to a point known as the Red Butte, or where the road leaves the river; thence along the range of mountains known as the Black Hills, to the head-waters of Heart River; thence down Heart River to its mouth; and thence down the Missouri River to the place of beginning. | Sioux |

| The territory of the Gros Ventre, Mandans, and Arrickaras Nations, commencing at the mouth of Heart River; thence up the Missouri River to the mouth of the Yellowstone River; thence up the Yellowstone River to the mouth of Powder River in a southeasterly direction, to the head-waters of the Little Missouri River; thence along the Black Hills to the head of Heart River, and thence down Heart River to the place of beginning. | Gros Ventre, Mandan, Arrickaras. |

| The territory of the Assiniboin Nation, commencing at the mouth of Yellowstone River; thence up the Missouri River to the mouth of the Muscle-shell River; thence from the mouth of the Muscle-shell River in a southeasterly direction until it strikes the head-waters of Big Dry Creek; thence down that creek to where it empties into the Yellowstone River, nearly opposite the mouth of Powder River, and thence down the Yellowstone River to the place of beginning. | Assiniboin. |

| The territory of the Blackfoot Nation, commencing at the mouth of Muscle-shell River; thence up the Missouri River to its source; thence along the main range of the Rocky Mountains, in a southerly direction, to the head-waters of the northern source of the Yellowstone River; thence down the Yellowstone River to the mouth of Twenty-five Yard Creek; thence across to the head-waters of the Muscle-shell River, and thence down the Muscle-shell River to the place of beginning. | Blackfoot. |

| The territory of the Crow nation, commencing at the mouth of Powder River on the Yellowstone; thence up the Powder River to its source; thence along the main range of the Black Hills and Wind River Mountains to the head-waters of the Yellowstone River; thence down the Yellowstone River to the mouth of Twenty-five Yard Creek; thence to the head waters of the Muscle-shell River; thence down the Muscle-shell River to its mouth; thence to the head-waters of Big Dry Creek, and thence to its mouth. | Crow. |

| The territory of the Cheyennes and Arrapahoes, commencing at the Red Butte, or the place where the road leaves the north fork of the source; thence along the main range of the Rocky Mountains to the head-waters of the Arkansas River; thence down the Arkansas River to the crossing of the Santa Fe road, thence in a northwesterly direction to the forks of the Platte River, and thence up the Platte River to the place of beginning. | Cheyenne & Arapaho. |

| It is, however, understood that, in making this recognition and acknowledgment, the aforesaid Indian nations do not hereby abandon or prejudice any rights or claims they may have to other lands; and further, that they do not surrender the privilege of hunting, fishing, or passing over any of the tracts of country heretofore described. | Rights to other lands. |

| Article 6 | |

| The parties to the second part of this treaty having selected principals or head-chiefs for their respective nations, through whom all national business will hereafter be conducted, do hereby bind themselves to sustain said chiefs and their successors during good behavior. | Head chiefs of said tribes. |

| Article 7 | |

| In consideration of the treaty stipulations, and for the damages which have or may occur by reason thereof to the Indian nations, parties hereto, and for their maintenance and the improvement of their moral and social customs, the United States bind themselves to deliver to the said Indian nations the sum of fifty thousand dollars per annum for the term of ten years, with the right to continue the same at the discretion of the President of the United States for a period not exceeding five years thereafter, in provisions, merchandise, domestic animals, and agricultural implements, in such proportions as may be deemed best adapted to their condition by the President of the United States, to be distributed in proportion to the population of the aforesaid Indian nations. | Annuities. |

| Article 8 | |

| It is understood and agreed that should any of the Indian nations, parties to this treaty, violated any of the provisions thereof, the United States may withhold the whole or a portion of the annuities mentioned in the preceding article from the nation so offending, until, in the opinion of the President of the United States, proper satisfaction shall have been made. | Annuities suspended by violation of treaty. |

In testimony whereof the said D.D. Mitchell and Thomas Fitzpatrick commissioners as aforesaid, and the chiefs, headmen, and braves, parties hereto, have set their hands and affixed their marks on the day and at the place first above written.

- "D.D. Mitchell

- Thomas Fitzpatrick

- Commissioners.

- SIOUX:

- Mah-toe-wha-you-whey, his x mark

- Mah-kah-toe-zah, his x mark

- Bel-o-ton-kah-tan-ga, his x mark

- Nah-ka-pah-gi-gi, his x mark

- Mak-toe-sah-bi-chis, his x mark

- Meh-wha-tah-ni-hans-kah, his x mark

- CHEYENNES: Wah-ha-nis-satta, his x mark

- Nahk-ko-me-ien, his x mark

- Voist-ti-toe-vetz, his x mark

- Koh-kah-y-wh-cum-est, his x mark

- ARRAPAHOES: Be-ah-té-a-qui-sah, his x mark

- Neb-ni-bah-she-it, his x mark

- Beh-kah-jay-beth-sah-es, his x mark

- CROWS: Arra-tu-r-sash, his x mark

- Doh-chepit-seh-chi-es, his x mark

- ASSINIBOINES: Mah-toe-it-ko, his x mark

- Toe-tah-ki-eh-nan, his x mark

- MANDANS AND GROS VENTRES: Nochk-pit-shi-toe-pish, his x mark

- She-oh-mant-ho, his x mark

- ACRICKAREES:F Koun-hei-ti-shan, his x mark

- Bi-atch-tah-wetch, his x mark

- In the presence of: A.B. Chambers, secretary

- S. Cooper, colonel, U.S. Army

- R.H. Chilton, captain, First Drags

- Thomas Duncan, captain, Mounted Riflemen

- Thos. G. Rhett, brevet captain R.M.R.

- W.L. Elliot, first lieutenant R.M.R.

- C. Campbell, interpreter for Sioux

- John S. Smith, interpreter for Cheyennes

- Robert Meldrum, interpreter for the Crows

- H. Culbertson, interpreter for Assiniboines and Gros Ventres

- Francois L. ’Etalie, interpreter for Arickarees

- John Pizelle, interpreter for the Arrapohoes

- B. Gratz Brown

- Robert Campbell

- Edmond F. Chouteau

This treaty as signed was ratified by the U.S. Senate with an amendment changing the annuity in Article 7 from fifty to ten years, subject to acceptance by the tribes. Assent of all tribes except the Crows was procured (See Upper Platte C., 570, 1853, Indian Office.) and in subsequent agreements this treaty has been recognized as in force. (See post p. 776.)

Treaty 1868

The 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty

TREATY WITH THE SIOUX—BRULÉ, OGLALA, MINICONJOU, YANKTONAI, HUNKPAPA, BLACKFEET, CUTHEAD, TWO KETTLE, SANS ARCS, SANTEE, AND ARAPAHO, 1868.

| Articles of a treaty made and concluded by and between Lieutenant-General William T. Sherman, General William S. Harney, General Alfred H. Terry, General C. C. Augur, J.B. Henderson, Nathaniel G. Taylor, John B. Sanborn, and Samuel F. Tappan, duly appointed commissioners on the part of the United States, and the different bands of the Sioux Nation of Indians, by their chiefs and head-men, whose names are hereto subscribed, they being duly authorized to act in the premises. | April 29 1869 15 Stats, 635 Ratified Feb. 16, 1869 Proclaimed, Feb. 24, 1869 |

| Article 1 | |

| From this day forward all war between the parties to this agreement shall forever cease. The Government of the United States desires peace, and its honor is hereby pledged to keep it. The Indians desire peace, and they now pledge their honor to maintain it. | War to cease and peace to be kept. |

| If bad men among the whites, or among other people subject to the authority of the United States, shall commit any wrong upon the persons or property of the Indians, the United States will, upon proof made to the agent and forwarded to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs at Washington City, proceed at once to cause the offender to be arrested and punished according to the laws of the United States, and also reimburse the injured person for the loss sustained. | Offenders against the Indians to be arrested, etc. |

| If bad men among the Indians shall commit a wrong or depredation upon the person or property of anyone, white, black, or Indian, subject to the authority of the United States, and at peace therewith, the Indians herein named solemnly agree that they will, upon proof made to their agent and notice by him, deliver up the wrong-doer to the United States, to be tried and punished according to its laws; and in case they willfully refuse so to do, the person injured shall be reimbursed for his loss from the annuities or other moneys due or to become due to them under this or other treaties made with the United States. And the President, on advising with the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, shall prescribe such rules and regulations for ascertaining damages under the provisions of this article as in his judgment may be proper. But no one sustaining loss while violating the provisions of this treaty or the laws of the United States shall be reimbursed therefor. | |

| Wrongdoers against the whites to be punished. | |

| Damages. | |

| Article 2 | |

| The United States agrees that the following district of country, to wit, viz: commencing on the east bank of the Missouri River where the forty-sixth parallel of north latitude crosses the same, thence along low-water mark down said east bank to a point opposite where the northern line of the State of Nebraska strikes the river, thence west across said river, and along the northern line of Nebraska to the one hundred and fourth degree of longitude west from Greenwich, thence north on said meridian to a point where the forty-sixth parallel of north latitude intercepts the same, thence due east along said parallel to the place of beginning; and in addition thereto, all existing reservations on the east bank of said river shall be, and the same is, set apart for the absolute and undisturbed use and occupation of the Indians herein named, and for such other friendly tribes or individual Indians as from time to time they may be willing, with the consent of the United States, to admit amongst them; and the United States now solemnly agrees that no persons except those herein designated and authorized so to do, and except such officers, agents, and employees of the Government as may be authorized to enter upon Indian reservations in discharge of duties enjoined by law, shall ever be permitted to pass over, settle upon, or reside in the territory described in this article, or in such territory as may be added to this reservation for the use of said Indians, and henceforth they will and do hereby relinquish all claims or right in and to any portion of the United States or Territories, except such as is embraced within the limits aforesaid, and except as hereinafter provided. | |

| Reservation boundaries. | |

| Certain persons not to enter or reside thereon. | |

| Article 3 | |

| If it should appear from actual surveyor other satisfactory examination of said tract of land that it contains less than one hundred and sixty acres of tillable land for each person who, at the time, may be authorized to reside on it under the provisions of this treaty, and a very considerable number of such persons shall be disposed to commence cultivation the soil as farmers, the United States agrees to set apart, for the use of said Indians, as herein provided, such additional quantity of arable land, adjoining to said reservation, or as near to the same as it can be obtained as may be required to provide the necessary amount. | Additional arable land to be added, if, etc. |

| Article 4 | |

|

The United States agrees, at its own proper expense, to construct at some place on the Missouri River, near the center of said reservation, where timber and water may be convenient, the following buildings, to wit: a warehouse, a store-room for the use of the agent in storing goods belonging to the Indians, to cost not less than twenty-five hundred dollars; and agency-building for the residence of the agent, to cost not exceeding three thousand dollars; a residence for the physician, to cost not more than three thousand dollars; and five other buildings, for a carpenter, farmer, blacksmith, miller, and engineer, each to cost not exceeding two thousand dollars; also a school-house or mission building, so soon as a sufficient number of children can be induced by the agent to attend school, which shall not cost exceeding five thousand dollars. The United States agrees further to cause to be erected on said reservation, near the other buildings herein authorized, a good steam circular-saw mill, with a grist-mill and shingle-machine attached to the same, to cost not exceeding eight thousand dollars. |

Buildings on reservation. |

| Article 5 | |

| The United States agrees that the agent for said Indians shall in the future make his home at the agency-building; that he shall reside among them, and keep an office open at all times for the purpose of prompt and diligent inquiry into such matters of complaint by and against the Indians as may be presented for investigation under the provisions of their treaty stipulations, as also for the faithful discharge of other duties enjoined on him by law. In all cases of depredation on person or property he shall cause the evidence to be taken in writing and forwarded, together with his findings, to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, whose decision, subject to the revision of the Secretary of the Interior, shall be binding on the parties to this treaty. | Agent’s residence, office, and duties. |

| Article 6 | |

| If any individual belonging to said tribes of Indians, or legally incorporated with them, being the head of a family, shall desire to commence farming, he shall have the privilege to select, in the presence and with the assistance of the agent then in charge, a tract of land within said reservation, not exceeding three hundred and twenty acres in extent, which tract, when so selected, certified, and recorded in the “land-book,” as herein directed, shall cease to be held in common, but the same may be occupied and held in the exclusive possession of the person selecting it, and of his family, so long as he or they may continue to cultivate it. | Heads of families may select lands for farming. |

| Any person over eighteen years of age, not being the head of a family, may in like manner select and cause to be certified to him or her, for purposes of cultivation, a quantity of land not exceeding eighty acres in extent, and thereupon be entitled to the exclusive possession of the same as above directed. | Others may select land for cultivation. |

| For each tract of land so selected a certificate, containing a description thereof and the name of the person selecting it, with a certificate endorsed thereon that the same has been recorded, shall be delivered to the party entitled to it, by the agent, after the same shall have been recorded by him in a book to be kept in his office, subject to inspection, which said book shall be known as the “Sioux Land Book.” | Certificates. |

| The President may, at any time, order a survey of the reservation, and, when so surveyed, Congress shall provide for protecting the rights of said settlers in their improvements, and may fix the character of the title held by each. The United States may pass such laws on the subject of alienation and descent of property between the Indians and their descendants as may be thought proper. And it is further stipulated that any male Indians, over eighteen years of age, of any band or tribe that is or shall hereafter become a party to this treaty, who now is or who shall hereafter become a resident or occupant of any reservation or Territory not included in the tract of country designated and described in this treaty for the permanent home of the Indians, which is not mineral land, nor reserved by the United States for special purposes other than Indian occupation, and who shall have made improvements thereon of the value of two hundred dollars or more, and continuously occupied the same as a homestead for the term of three years, shall be entitled to receive from the United States a patent for one hundred and sixty acres of land including his said improvements, the same to be in the forms of the legal subdivision of the surveys of the public lands. Upon application in writing, sustained by the proof of two disinterested witnesses, made to the register of the local land-office when the land sought to be entered is within a land district, and when the tract sought to be entered is not in any land district, then upon is a application and proof being made to the Commissioner of the General Land-Office, and the right of such Indian or Indians to enter such tract or tracts of land shall accrue and be perfect from the date of his first improvements thereon, and shall continue as long as he continues his residence and improvements, and no longer. And any Indian or Indians receiving a patent for land under the foregoing provisions, shall thereby and from thenceforth become and be a citizen of the United States, and be entitled to all the privileges and citizen of the United States, and be entitled to all the privileges and immunities of such citizens, and shall, at the same time, retain all his rights to benefits accruing to Indians under this treaty. | |

| Surveys. | |

| Alienation and descent of property. | |

| Certain Indians may receive patents for 160 acres of land. | |

| Such Indians receiving patents become citizens of the United States. | |

| Article 7 | |

| In order to insure the civilization of the Indians entering into this treaty, the necessity of education is admitted, especially of such of them as are or may be settled on said agricultural reservations, and they therefore pledge themselves to complete their children, male and female, between the ages of six and sixteen years, to attend school; and it is hereby made the duty of the agent for said Indians to see that this stipulation is strictly complied with; and the United States agrees that for every thirty children between said ages who can be induced or compelled to attend school, a house shall be provided and a teacher competent to teach the elementary branches of an English education shall be furnished, who will reside among said Indians, and faithfully discharge his or her duties as a teacher. The provisions of this article to continue for not less than twenty years. | |

| Education. | |

| Children to attend school. | |

| Schoolhouses and teachers. | |

| Article 8 | |

| When the head of a family or lodge shall have selected lands and received his certificate as above directed, and the agent shall be satisfied that he intends in good faith to commence cultivating the soil for a living, he shall be entitled to receive seed and agricultural implements for the first year, not exceeding in value one hundred dollars, and for each succeeding year he shall continue to farm, for a period of three years more, he shall be entitled to receive seeds and implements as aforesaid, not exceeding in value twenty-five dollars. | Seeds and agricultural implements. |

| And it is further stipulated that such persons as commence farming shall receive instruction from the farmer herein provided for, and whenever more than one hundred persons shall enter upon the cultivation of the soil, a second blacksmith shall be provided, with such iron, steel, and other material as may be needed. | |

| Instructions in farming. | |

| Second blacksmith. | |

| Article 9 | |

| At any time after ten years from the making of this treaty, the United States shall have the privilege of withdrawing the physician, farmer, blacksmith, carpenter, engineer, and miller herein provided for, but in case of such withdrawal, an additional sum thereafter of ten thousand dollars per annum shall be devoted to the education of said Indians, and the Commissioner of Indian Affairs shall, upon careful inquiry into their condition, make such rules and regulations for the expenditure of said sum as will best promote the educational and moral improvement of said tribes. | |

| Physician, farmer, etc., may be withdrawn. | |

| Additional appropriation in such cases. | |

| Article 10 | |

| In lieu of all sums of money or other annuities provided to be paid to the Indians herein named, under any treaty or treaties heretofore made, the United States agrees to deliver at the agency-house on the reservation herein named, on or before the first day of August of each year, for thirty years, the following articles, to wit: | Delivery of goods in lieu of money or other annuities. |

|

For each male person over fourteen years of age, a suit of good substantial woolen clothing, consisting of coat, pantaloons, flannel shirt, hat, and a pair of home-made socks. For each female over twelve years of age, a flannel skirt, or the goods necessary to make it, a pair of woolen hose, twelve yards of calico, and twelve yards of cotton domestics. For the boys and girls under the ages named, such flannel and cotton goods as may be needed to make each a suit as aforesaid, together with a pair of woolen hose for each. |

Clothing. |

| And in order that the Commissioner of Indian Affairs may be able to estimate properly for the articles herein named, it shall be the duty to forward to him a full and exact census of the Indians, on which the estimate from year to year can be based. | Census. |

| And in addition to the clothing herein named, the sum of ten dollars for each person entitled to the beneficial effects of this treaty shall be annually appropriated for a period of thirty years, while such persons roam and hunt, and twenty dollars for each person who engages in farming, to be used by the Secretary of the Interior in the purchase of such articles as from time to time the condition and necessities of the Indians may indicate to be proper. And if within the thirty years, at any time, it shall appear that the amount of money needed for clothing under this article can be appropriated to better uses for the Indians named herein, Congress may, by law, change the appropriation to their purposes; but in no event shall the amount of this appropriation be withdrawn or discontinued for the period named. And the President shall annually detail an officer of the Army to be present and attest the delivery of all the goods herein named to the Indians, and he shall inspect and report on the quantity and quality of the goods and manner of their delivery. And it is hereby expressly stipulated that each Indian over the age of four years, who shall have removed to and settled permanently upon said reservation and complied with the stipulations of this treaty, shall be entitled to receive from the United States, for the period of four years after he shall have settled upon said reservation, one pound of meat and one pound of flour per day, provided the Indians cannot furnish their own subsistence at an earlier date. And it is further stipulated that the United States will furnish and deliver to each lodge of Indians or family of persons legally incorporated with them, who shall remove to the reservation herein described and commence farming, one good American cow, and one good well-broken pair of American oxen within sixty days after such lodge or family shall have so settled upon said reservation. | |

| Other necessary articles. | |

| Appropriation to continue for thirty years. | |

| Army officer to attend the delivery. | |

| Meat and flour. | |

| Cows and oxen. | |

| Article 11 | |

|

In consideration of the advantages and benefits conferred by this treaty, and the many pledges of friendship by the United States, the tribes who are parties to this agreement hereby stipulate that they will relinquish all right to occupy permanently the territory outside their reservation as herein defined, but yet reserve the right to hunt on any lands north of North Platte, and on the Republican Fork of the Smoky Hill River, so long as the buffalo may range thereon in such numbers as to justify the chase. And they, the said Indians, further expressly agree: 1st. That they will withdraw all opposition to the construction of the railroads now being built on the plains. 2nd. That they will permit the peaceful construction of any railroad not passing over their reservation as herein defined. 3rd. That they will not attack any persons at home, or travelling, nor molest or disturb any wagon trains, coaches, mules, or cattle belonging to the people of the United States, or to persons friendly therewith. 4th. They will never capture, or carry off from the settlements, white women or children. 5th. They will never kill or scalp white men, nor attempt to do them harm. 6th. They withdraw all pretence of opposition to the construction of the railroad now being built along the Platte River and westward to the Pacific Ocean, and they will not in future object to the construction of railroads, wagon-roads, mail stations, or other works of utility or necessity, which may be ordered or permitted by the laws of the United States. But should such roads or other works be constructed on the lands of their reservation, the Government will pay the tribe whatever amount of damage may be assessed by three disinterested commissioners to be appointed by the President for that purpose, one of said commissioners to be a chief or head-man of the tribe. 7th. They agree to withdraw all opposition to the military posts or roads now established south of the North Platte River, or that may be established, not in violation of treaties heretofore made or hereafter to be made with any of the Indian tribes. |

|

| Right to occupy territory outside of the reservation surrendered. | |

| Right to hunt reserved. | |

| Agreement as to railroads. | |

| Emigrants, etc. | |

| Women and children. | |

| White man. | |

| Pacific Railroad, wagon roads, etc. | |

| Damage for crossing their reservation. | |

| Military posts and roads. | |

| Article 12 | |

| No treaty for the cession of any portion or part of the reservation herein described which may be held in common shall be of any validity or force as against the said Indians, unless executed and signed by at least three fourths of all the adult male Indians, occupying or interested in the same; and no cession by the tribe shall be understood or construed in such manner as to deprive, without his consent, any individual member of the tribe of his rights to any tract of land selected by him, as provided in Article 6 of this treaty. | No treaty for cession of reservation to be valid unless, etc. |

| Article 13 | |

| The United States hereby agrees to furnish annually to the Indians the physician, teachers, carpenter, miller, engineer, farmer, and blacksmiths as herein contemplated, and that such appropriations shall be made from time to time, on the estimates of the Secretary of the Interior, as will be sufficient to employ such persons. | United States to furnish physician, teachers, etc. |

| Article 14 | |

| It is agreed that the sum of five hundred dollars annually, for three years from date, shall be expended in presents to the ten persons of said tribe who in the judgment of the agent may grow the most valuable crops for the respective year. | Presents for crops. |

| Article 15 | |

| The Indians herein named agree that when the agency-house or other buildings shall be constructed on the reservation name, they will regard said reservation their permanent home, and they will make no permanent settlement elsewhere: but they shall have the right, subject to the conditions and modifications of this treaty, to hunt, as stipulated in Article 11 hereof. | Reservation to be permanent home for tribes. |

| Article 16 | |

| The United States hereby agrees and stipulates that the country north of the North Platte River and east of the summits of the Big Horn Mountains shall be held and considered to be un-ceded Indian territory, and also stipulates and agrees that no white person or persons shall be permitted to settle upon or occupy any portion of the same; or without the consent of the Indians first had and obtained, to pass through the same; and it is further agreed by the United States that within ninety days after the conclusion of peace with all the bands of the Sioux Nation, the military posts now established in the territory in this article named shall be abandoned, and that the road leading to them and by them to the settlements in the Territory of Montana shall be closed. | |

| Un-ceded Indian territory. | |

| Not to be occupied by whites, etc. | |

| Article 17 | |

| It is hereby expressly understood and agreed by and between the respective parties to this treaty that the execution of this treaty and its ratification by the United States Senate shall have the effect, and shall be construed as abrogating and annulling all treaties hereto, so far as such treaties and agreements obligate the United States to furnish and provide money, clothing, or other articles of property to such Indians and bands of Indians as become parties to their treaty, but no further. | Effect of this treaty upon former treaties. |

In testimony of all which, we, the said commissioners, and we, the chiefs and headmen of the Brulé band of the Sioux nation, have hereunto set our hands and seals at Fort Laramie, Dakota Territory, this twenty-ninth day of April, in the year one thousand eight hundred and sixty-eight.

- N.G. Taylor, [SEAL.]

- W.T. Sherman, Lieutenant-Genera1. [SEAL.]

- Wm. S. Harney, Brevet Major-General U.S. Army. [SEAL.]

- John B. Sanborn, [SEAL.]

- S.P. Tappan, [SEAL.]

- C.C. Augur, Brevet Major-General. [SEAL.]

- Alfred H. Terry, Brevet Major-General U.S. Army. [SEAL.]

- Attest:

- A.S.H. White, Secretary.

Executed on the part of the Brulé band of Sioux by the chiefs and headmen whose names are hereto annexed, they being thereunto duly authorized, at Fort Laramie, D.T., the twenty-ninth day of April, in the year A.D. 1868.

- Ma-za-pon-kaska, his x mark, Iron Shell. [SEAL.]

- Wah-pat-shah, his x mark, Red Leaf. [SEAL.]

- Hah-sah-pah, his x mark, Black Horn. [SEAL.]

- Zin-tah-gah-lat-skah, his x mark, Spotted Tail. {SEAL.]

- Zin-tah-skah, his x mark, White Tail. [SEAL.]

- Me-wah-tah-ne-ho-skah, his x mark, Tall Mandas. [SEAL.]

- She-cha-chat-kah, his x mark, Bad Left Hand. [SEAL.]

- No-mah-no-pah, his x mark. Two and Two. [SEAL.]

- Tah-tonka-skah, his x mark, White Bull. [SEAL.]

- Con-ra-washta, his x mark, Pretty Coon. [SEAL.]

- Ha-cah-cah-she-chah, his x mark, Bad Elk. [SEAL.]

- Wa-ha-ka-zah-ish-tab, his mark, Eye Lance. [SEAL.]

- Ma-to-ha-ke-tah, his x mark, Bear that looks behind. [SEAL.]

- Bella-tonka-tonka, his x mark, Big Partisan. [SEAL.]

- Mah-to-ho-honka, his x mark, Swift Bear. [SEAL.]

- To-wis-ne, his x mark, Cold Place. [SEAL.]

- Ish-tah-skah, his x mark, White Eyes. [SEAL.]

- Ma-ta-loo-zah, his x mark, Fast Bear. [SEAL.]

- As-hah-kah-nah-zhe, his x mark, Standing Elk.. [SEAL.]

- Shunka-shaton, his x mark, Day Hawk. [SEAL.]

- Can-te-te-ki-ya, his x mark, The Brave Heart. [SEAL.]

- Tatanka-wakon, his x mark, Sacred Bull. [SEAL.]

- Mapia shaton, his x mark, Hawk Cloud. [SEAL.]

- Ma-sha-a-ow, his x mark, Stands and Comes. [SEAL.]

- Shon-ka-ton-ka, his x mark, Big Dog. [SEAL.]

- Attest:

- Ashton S. H. White, secretary of commission.

- George B. Withs, photographer to commission.

- Geo. H. Holtzman.

- John D. Howland.

- James C. O’Connor.

- Charles E. Guern, interpreter.

- Leon F. Pallardy, interpreter.

- Nicholas Janis, interpreter.

Kapplers, Charles (1972). Indian Laws and Treaties. Interland Publishing Inc., New York. pp. 591–596.

Execution by the Ogallalah.