Winter Count

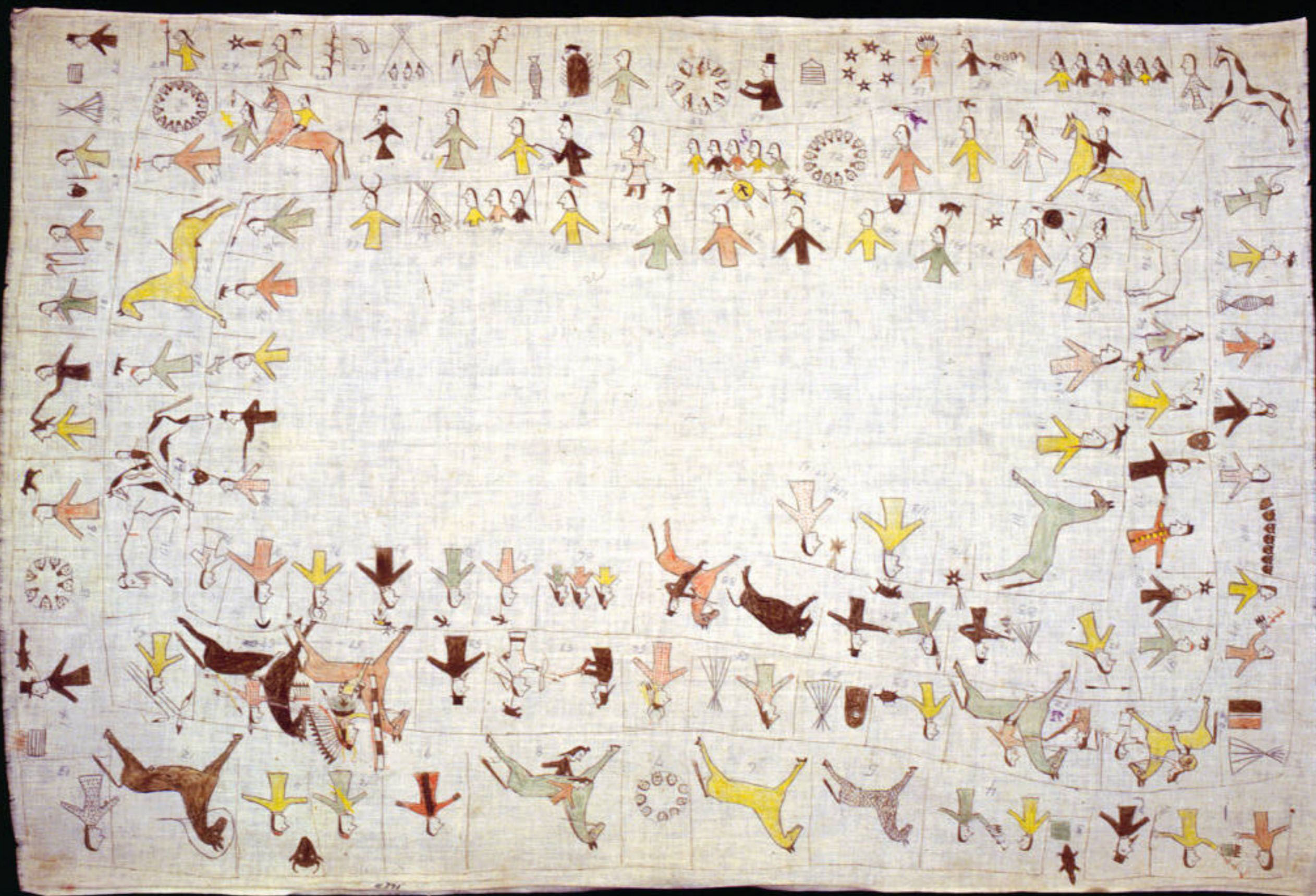

Waniyetu Wowapi (High Dog's Winter Count, 1798 - 1912)

Many indigenous groups in the Americas have used mnemonic devices—carvings, beaded belts, or drawings—to reinforce memories of tribal history. One type of record common among native people of the Plains is the pictographic waniyetu wowapi, or winter count, painted on animal hide and later on unbleached muslin. The tribal historian with the counsel of the old men of his tribe, decided on some event that distinguished each year and then drew an appropriate symbol for that year. Every adult could describe the events portrayed and used the calendar-like device as a visual aid when educating the tribe’s children or retelling the tribe’s history at gatherings. The Dakota and Lakota refer to these documents as waiyetu wowapi or “winter counts” because the people counted their years by winters, and so the Dakota year covered portions of two calendar years.

|

|

|

High Dog, a Hunkpapa from the Standing Rock Reservation, kept such a winter count which is now part of the holdings at the State Historical Society of North Dakota. High Dog’s winter count represents the years 1798 to 1912. An earlier version of this count (probably drawn on animal hide) was passed on to High Dog from a previous tribal historian. As was common practice, High Dog then copied the images from the past and learned the meaning of each, thus insuring that his tribe’s history would survive for succeeding generations.

In many winter counts painted before Native Americans were restricted to reservations, the drawings moved in a spiral from inside out. Most winter counts painted during the reservation years—including High Dog’s—move from outside inward. Some observers have remarked that this change in pattern seems to symbolize the shift in Native American life: from the early days, when the traditions and values were intact, to the reservation period, when a new time was upon the people and the old time was fading away, and the days of traditional Native American life appeared to be numbered.

1. 1798

“THE YEAR FOUR MEN WERE SET APART WITH BLUE FEATHERS.”

Blue feathers were worn by community leaders or elders whom the people greatly respected. Sometimes a child was given a blue feather because some sign at birth indicated superior wisdom. Adults were raised to this rank for distinguished service to the tribe or for outstanding wisdom. Members of this group were expected to admonish others greatly, honor and respect older people, be kind to humans and animals, be generous, and be an example of virtue and goodness to others.

2. 1803

“THE YEAR THE SIOUX CAPTURED SOME SHOD HORSES FROM THE CROWS.”

This was the first time High Dog’s people had seen shoes on horses (horseshoes), although they knew that white men’s horses wore them. Some believed that white men’s horses were trained to strike an enemy with these iron weapons.

3. 1820

“THE YEAR THEY CELEBRATED THE SUN DANCE.”

The Sun Dance is one of the seven sacred rites brought to the Lakota people by the White Buffalo Calf Woman. The time of the Sun Dance is a very holy time when the people come together and offer prayers.

4. 1829

“THE YEAR A MAN LOOKING FOR A BUFFALO WAS FOUND ON THE PRAIRIE SHOT AND FROZEN. HE IS CALLED FROZE ON-THE-PRAIRIE.”

Suicide at this time was practically unknown among the Plains Indians. The man probably shot himself by accident.

5. 1833

“STARS-ALL-MOVING YEAR.”

Falling stars were a cause of great wonder this year.

6. 1834

“THE YEAR THE FIRST WAR BONNET WAS MADE WITH HORNS ON IT.”

The story of this drawing is not clear. The war bonnet was undoubtedly part of a warrior society or medicine society regalia. In any case, a man who wore such a headdress had responsibility to assist his people.

7. 1837

“THE YEAR SMALLPOX CARRIED OFF TO WANAGI YAKONPI (THE OTHER WORLD) MANY OF THE SUFFERING PEOPLE.”

The devastation caused by white men’s diseases including smallpox and measles is often referred to in this winter count.

8. 1856

“THE YEAR GOOD BEAR TORE A WAR BONNET FROM A CROWS HEAD IN A FIGHT.”

Many drawings in the winter count focus on the tribe’s rivalry with the Crows. More than thirty images reflect individual skirmishes or full-blown battles between the two tribes, with the Sioux more often portrayed as the victors. Warfare at this time was pointed at besting an enemy by counting coup on him, or in this case, taking his war bonnet.

9. 1866

“THE YEAR PIZI WAS HELD PRISONER BY GENERAL NELSON MILES.”

Pizi, or Gall, was a great warrior among his people, the Hunkpapa. Many of his people feared Miles killed him. Gall became most famous for his exploits on the battlefield of the Little Bighorn on June 25, 1876, when Custer and his men were defeated.

10. 1883

“THE YEAR WHITE BEARD WENT ON A BUFFALO HUNT WITH THE INDIANS.”

“White Beard” refers to Standing Rock Indian agent James McLaughlin who went on the last big buffalo hunt in North Dakota with the Sioux of Standing Rock Agency. This was a happy, though brief, interlude for the people who were now forced to eat government rations most of the time.

11. 1900

“THE YEAR HAWK SHIELD DIED.”

The last twenty-seven years of High Dog’s winter count (from 1885) is primarily a list of individuals who died. With only four few exceptions (including “The sun turned black and died” and “A star died”), individual deaths are the only events to mark these years. As the Hunkpapa transitioned to the new way of reservation life those people who knew and lived the old ways were memorialized for their wisdom and knowledge of the traditional life, and their contributions to their people were marked as they passed from this world.

1650s-1862

1650s

Dakota and Lakota bands hunted buffalo on the Plains in summer, and lived in north woods area of Minnesota in winter.

1700

Teton bands are living full-time in northern Plains as nomadic buffalo hunters.

1742

Probable date for acquisition of horse among the Tetons.

1750

Yanktonai (Middle Sioux) settled along eastern side of Missouri River. They pursued the buffalo, acquired horses and tepees; eventually some bands farmed and lived in earthlodges.

1787

July 13—The Northwest Ordinance is passed by the Continental Congress, stating that “the utmost good faith shall always be observed towards the Indians; their lands and property shall never be taken from them without their consent; and in the property rights and liberty, they never shall be invaded or disturbed.”

September 17—The U.S. Constitution is adopted. Article I, section 8, grants Congress the power to “regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian tribes.” This establishes a government-to-government relationship with tribes. Consequently the federal government, rather than states, is involved in Indian affairs.

1789

Congress gives the War Department authority over Indian affairs.

1794

First Indian treaty included provisions for education of Indians by the United States and the Oneidas, Tuscaroras, and Stockbridge.

1802

The U.S. Congress appropriates ten to fifteen thousand dollars annually to promote “civilization” among the Indians. This money goes to Christian missionary organizations working to convert Indians to Christianity.

1803

United States negotiates the Louisiana Purchase with France, thereby acquiring vast amounts of land inhabited by Indians in the Northern Plains. The purchase increases American contact with Yanktonai and Hunkpatina living east of the Missouri River.

1804 – 1806

Lewis and Clark Expedition to the Pacific Northwest make first American contact with many northern tribes.

1804

On October 18th, the Lewis and Clark Expedition had contact with Yanktonai band in the area of present-day Cannonball, North Dakota.

1819

Congress appropriates money for the “Civilization Fund,” the first federal Indian education program. Christian missionary societies received this money to establish schools among Indian people.

1824

The secretary of war creates a Bureau of Indian Affairs within the War Department.

1825

General Henry Atkinson and Major Benjamin O’Fallon met with a number of Missouri River tribes to establish treaties of peace and friendship. In actuality the U.S. wanted to curtail British trading with tribes in the area. Treaty negotiated with Teton, Yankton, and Yanktonai at Fort Lookout along Missouri River on June 22, 1825. In the treaty, the Indians acknowledged the right of the U.S. to regulate trade and intercourse with them, promised to return horses stolen from Americans, and promised not to furnish guns to tribes hostile to the U.S. In return, the U.S. promised to provide friendship and protection, and to furnish licensed traders in their territory.

August 19—Some Yanktonai from the Dakotas sign Prairie du Chien Treaty. It established specific boundaries and territories for tribes involved: Yanktonai, Chippewa, Sac and Fox; Menominee, Iowa, Winnebago, Ottawa, and Potawatomi. Each tribe gave up any claims to be in designated territory of another tribe or hunt in that territory without permission. The U.S. was interested in establishing one tribe in one area to facilitate land cessions. The government soon began dealing with each tribe to acquire their treaty lands.

1833 – 1834

A German prince, Maximilian of Wied-Neuwied, and Swiss artist Karl Bodmer, traveled up the Missouri River, spent the winter at Fort Clark (northwest of the present city of Bismarck, North Dakota). Yanktonai visited and Bodmer painted a portrait of Psihdje-Sahpa.

1837

Smallpox epidemic kills more than 15,000 Indians in the Upper Missouri River including over 400 Yanktonai.

1849

Bureau of Indian Affairs is transferred from the War Department to the newly created Department of the Interior.

1851

Santee negotiate Treaty of Traverse des Sioux and Treaty of Mendota with U.S. ceding much of their Minnesota homeland to the U.S. in return for annuities payable over 50 years. Four Santee tribes were left with a reservation 150 miles long and 20 miles wide across the Minnesota River. The Yanktonai were angered by the cession, asserting they too lived in these lands and should have been part of the negotiations.

1851

September 17—After gold was discovered in California in 1849, traffic across Indian lands increased. U.S. holds Fort Laramie (Wyoming) Treaty Council with Plains and Mountain tribes to open central plains for transportation routes through Kansas and Nebraska. Tetons attend. Yanktonai omitted from treaty because their traditional areas were far removed from the overland route to the Pacific Coast which the treaty aimed to safeguard.

1856

Alfred J. Vaughn, agent for Upper Missouri tribes, reported a band of Yanktonai headed by Little Soldier built a permanent earthlodge village on the east bank of the Missouri River, above the mouth of Spring Creek, near present day Pollock, South Dakota.

1856–1857

Winter—Smallpox epidemic among Yanktonai killed many.

1858

Santee negotiate treaty with U.S. and their reservation as established in 1851 treaty is cut in half. The Yanktonai, along with the Tetons, oppose this treaty and claim rights in the ceded lands.

1861

Dakota Territory established. Yanktonai and Hunkpatina occupy areas of the east bank of the Missouri River.

Gold discovered on the headwaters of the Missouri River.

1862

Unresolved grievances lead to Santee Sioux uprising in Minnesota. Traders and agents defraud Indians of annuity monies; government annuities late and not distributed once they arrived. There is dissatisfaction with 1851 Treaty in general.

Settlers in Minnesota and the Dakota Territory, fearful of further troubles with Indians, demanded protection. There are many rumors of Santee Sioux from Minnesota fleeing onto Dakota prairies. Rumors and reports indicate unrest among Sioux who traditionally lived in Dakota Territory, including Yanktonai and Teton. Public pressure from newspapers, politicians, and general population demand Army action to protect frontier settlements.

1863-1874

1863

January 1—Dakota Territory opened for homesteading.

September 3—600–700 soldiers under General Alfred Sully attacked Yanktonai hunting camp at Whitestone Hill, Dakota Territory (near present-day Kulm, North Dakota). At least 300 Indians killed. 20 soldiers killed, some form their comrades’ bullets. Sully mistook the Yanktonai for Indians involved in the Minnesota uprising.

September 4 and 5—Sully ordered all Indian property at Yanktonai camp at Whitestone Hill destroyed as well as tons of dried buffalo meat and tallow. Entire winter meat supplies as well as all household goods of Yanktonai burned. Yanktonai were taken to the Crow Creek Agency as prisoners of war.

General Alfred Sully, in charge of about 2,200 troops, traveled up the Missouri River and selected a spot south of present-day Mandan, North Dakota for the construction of Fort Rice.

1864

July—General Alfred Sully leaves Fort Rice in search of Indian encampments.

July 28—Sully found a hunting camp of about 1,600 Yanktonai, Hunkpapa, Sihasapa, and other Teton groups near a branch of the Little Missouri River at Killdeer Mountain. Sully’s troops attack, killing about 100 Indians, and force them to leave behind most of their property at the campsite. The soldiers gather into heaps and burn tons of dried buffalo meat, great quantities of dried berries, buffalo robes, tepee covers and poles, and household utensils.

Sully chases remnants of the Sioux bands from the Killdeer Mountains into the North Dakota Badlands and attacks them along the Yellowstone River on August 12. The U.S. government is hopeful these Dakota and Lakota people will now be interested in a treaty after “their severe punishment in life and property for the last 2 years ...” (letter to Sully from John Pell, October 26, 1864)

1865

Treaties with Hunkpapa and Yanktonai at Fort Sully on October 20th. Treaty with Upper Yanktonai on October 28 at Fort Sully. Signers included Two Bears, Big Head, Little Soldier, and Black Catfish. In these treaties the Indians agreed to cease all hostilities with U.S. citizens and with members of other tribes. They also agree to withdraw from overland routes through their territory. They accept annuity payments and those who take up agriculture will receive implements and seed. Yanktonai hunting territories limited by treaty and this often led to starvation.

1866—1868

Red Cloud’s War. Red Cloud opposed the opening of the Bozeman Trail to travel by whites and the staffing of forts in the traditional hunting lands of the Teton. For two years he led the Oglalas and other Teton bands in battles against the United States Army and forced the U.S. to abandon the forts.

1868

U.S. signs Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 with Lakota, Dakota, Arapaho, and Cheyenne. This treaty confirms a permanent reservation for the Sioux in all of South Dakota west of the Missouri River, and the Indians in turn released all lands east of the Missouri River except the Crow Creek, Sisseton, and Yankton Reservations. In this treaty the government promised that no whites would enter the Sioux reservation without Sioux permission and that further negotiations must be ratified by the signature of three-fourths of the adult Sioux males. The Yanktonai, under Two Bears, voiced objections to the reservation proposal since they wish to remain on the east side of the Missouri River.

1869

Three agencies established along Missouri River to handle affairs on Great Sioux Reservation. These were Grand River Agency (moved and renamed Standing Rock in 1874), Cheyenne River Agency, and Whitestone Agency (renamed Spotted Tail in 1874).

1870–1886

Federal Indian policy forces Indians onto reservations, and is backed by military support. Since Indians are confined to the reservation area, the government begins to distribute food rations and clothing to the Indian people. The government withholds food rations from any Indian who opposes government policy, criticizes the agent, or practices Native American ceremonies or customs.

1870

Congress passes a law prohibiting army officers from being appointed Indian agents, prompting President Ulysses Grant to turn control of Indian agencies over to various Christian denominations to hasten “Christianization” of the Indians.

Grand River Agency (Standing Rock) assigned to Catholic Church. William F. Cady was the first agent. He assumed his duties in December 1870. Military post established at site of Grand River Agency to provide military support to government appointed agent.

1871

March 3 — Congress passes legislation formally ending treaty-making with Indian tribes. From now on the federal government will negotiate acts or agreements ratified by both the U.S. House and Senate. Acts and agreements have the force of law. All treaties remain legal.

June — Jesuit priests travel to Grand River Agency to determine if prospects are favorable for establishing a mission. After witnessing a sun dance they recommend no mission be established as the people are too entrenched in their traditional beliefs.

73 surveyors for the Northern Pacific Railroad invaded the Great Sioux Reservation in direct violation of the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty.

1873

Grand River Agency moved lo present-day Fort Yates, near military fort. Land better for farming and natural boat landing at this site.

Census at Standing Rock Agency reveals: Upper Yanktonai, 1,386; Lower Yanktonai, 2,534; Hunkpapa, 1,512; Blackfeet, 847.

1874

Census figures reveal the following populations: Upper Yanktonai, 1,406; Lower Yanktonai, 2,607; Hunkpapa, 1,556; and Blackfeet, 871. Many of the people still living in the un-ceded lands as provided in the 1868 Treaty are uncounted.

December — Rain-In-The Face, Hunkpapa, is arrested for killing two civilians under clouded circumstances on Sioux treaty lands. Blackfeet and Hunkpapa bands angry, more troops move onto agency to prevent problems. Tensions mount among Dakota and Lakota at Standing Rock after illegal intrusion into Black Hills.

Under government orders, George Armstrong Custer left Fort Abraham Lincoln, Dakota Territory, to lead a geological expedition into the Black Hills. Expedition is illegal according to the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty. Discovery of gold led to a stampede of goldseekers into the area in direct violation of the 1868 Treaty. Sioux protest to no avail. Bad feelings between federal officials and the Sioux escalate.

December 22 — Standing Rock Indian Agency is officially named. The name comes from a legend important to both Dakota and Lakota people.

Census figures reveal these populations at Standing Rock: Upper Yanktonai, 1,473; Lower Yanktonai, 2,730; Hunkpapa, 2,100; and Blackfeet, 1,019. Many remain uncounted as they live in un-ceded land.

June 6 — The Grand River military post is officially abandoned and transferred to site of Standing Rock Agency. The Post was named Fort Yates in December 1878 to honor Captain George Yates, killed at the battle of the Little Bighorn. In 1878 it became the largest Missouri River military post.

A federal commission meets to discuss the proposed sale of the Black Hills. Standing Rock Sioux initially refuse to attend the conference stating it is a sham. Eventually, they attend and join other members of the Sioux Nation in refusing to cede sacred Black Hills. Federal authorities continue to work on strategies in order to take the Black Hills.

1875 - 1888

1875 – 1876

Winter—All Lakota and Dakota living in un-ceded territory described in the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty were ordered to report to the Great Sioux Reservation. Bitter cold weather prevents army from embarking on winter campaign and forcing Indians onto reservation. Many Dakota and Lakota from Standing Rock Agency are in un-ceded lands that winter.

1876

August — Catholic priest, Father Martin Marty, arrives at Standing Rock Agency to begin missionary activities.

Census figures at Standing Rock reveal: Upper Yanktonai, 469; Lower Yanktonai, 794; Hunkpapa, 418; Blackfeet, 492; halfbreeds, 93; Indian scouts, 51. Significant numbers from all bands left reservation in early spring, as was their custom and right by law, to hunt in the un-ceded territories. Army ordered to force all Indians onto the Great Sioux Reservation.

June — George Custer left Fort Abraham Lincoln to take part in Army plan to gather all Sioux on the bounds of the Great Sioux Reservation.

June 17 — General Crook attacks Lakota bands in the Battle of the Rosebud (Montana). Crook’s troops are held back.

June 25 — Lt. Colonel Custer’s force of 267 men is annihilated by Lakota and Cheyenne at the Little Bighorn River in Montana.

After the Battle of the Little Bighorn, U.S. Army troops pour into the northern Plains to force all Dakota and Lakota onto the Great Sioux Reservation. All Indians must surrender their guns and horses and are held as prisoners of war on the reservation. U.S. begins to negotiate cession of the Black Hills with various bands of the Sioux Nation. Sioux people refuse to give up sacred Black Hills. Coercion, threats, and force by government officials cannot produce requisite signatures.

1877

Congress votes to take Black Hills from the Sioux in open violation of the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty which requires three-fourths of the adult Sioux males to approve. Government officials obtained few signatures.

Catholic boarding schools for boys and a separate one for girls open at Standing Rock. Bishop Marty initiated these efforts.

Benedictine priests opened another Catholic boarding school for boys at Standing Rock Agency. All boys had hair cut short and wore uniforms.

1878

Industrial farm school for boys established and located 15 miles south of Standing Rock Agency by Benedictine priest.

Hampton Institute in Hampton, Virginia, a non-sectarian Christian vocational school for educating ex-slaves, admits Indian students. Its motto is “Education for the Head, the Hand, and the Heart.” Many young people from Standing Rock are sent to Hampton.

December 16 — Standing Rock creates Indian police force as permitted by federal government. The police are under direct orders of federally appointed agent.

1879

Carlisle Indian School, Carlisle, Pennsylvania, opens. Its motto is “To Kill the Indian and Save the Man.” This is the first federally sponsored Indian school and it serves as a prototype where Indian children are removed from the home environment in order to hasten their “civilization into the white man’s world.” Young people from Standing Rock are sent to Carlisle.

1880

Catholic girls’ boarding school moved 15 miles south of Standing Rock Agency because Fort Yates soldiers annoy the girls.

1880–1881

Winter — Severe weather causes heavy losses of livestock at Standing Rock. Over one-third of cattle and horses die. Weather wreaks havoc with efforts by Indians to farm or ranch.

1883

Indian Offenses Act passed making practice of many Indian customs and all religious ceremonies illegal. The federal government outlawed these aspects of Indian life to hasten assimilation of Indians into the mainstream society and encourage acceptance of Christianity.

Hot winds and drought cause crop failure at Standing Rock Agency.

Catholic mission established at Cannonball.

Rev. T.L. Riggs of the American Missionary Society opens a day school at Antelope Settlement on the Grand River.

1884

Sioux at Standing Rock had 1,900 acres under cultivation. Each family at the agency had an individual plot.

1885

September 1 — Haskell Institute Training School, sponsored by the U.S. government, opens in Lawrence, Kansas.

1886

Commissioner of Indian Affairs requires English to be used in all Indian schools because “it is believed that teaching an Indian youth in his own barbarous dialect is a positive detriment to him.”

1886

Drought causes sparse crops at Standing Rock. Standing Rock Sioux farm communal plots according to band affiliation. They purchased mowers cooperatively and assist each other with tasks.

1886–1887

Severe winter causes Standing Rock Sioux to lose 30 percent of their cattle and horses. Average loss among non-Indian stockmen in Dakota-Montana area is 75 percent.

1887

February 8 — Congress passes the Dawes Allotment Act, providing for allotment of Indian lands in severalty. Few allotments are made on Standing Rock at this time. The purpose of this law was to break up the Indian land base, the reservation. After individual allotments were made, the government would open the remaining land to homesteading. Most Indians were allotted very poor quality lands.

1888

Pressure from citizens in the Dakotas results in a federal commission to break up the Great Sioux Reservation. Standing Rock, the first agency visited, overwhelmingly rejects the plan. Standing Rock’s firm stance against the bill kills it at this time.

1889-Present

1889

500 Standing Rock Sioux attend Fourth of July parade in Bismarck.

Word of the Ghost Dance religion, a pan-tribal religion, is heard on the Great Sioux Reservation. The religion, with origins among the Paiute in Nevada, promises a return to the old ways and is attractive to some Lakota and Dakota.

North Dakota and South Dakota are admitted to the Union.

Pressure from citizens of the Dakota Territory results in a federal commission, which seeks to break the Great Sioux Reservation into six smaller reservations and opens up nine million acres of land to homesteading. Despite opposition from the various bands, just over the requisite three-quarters of adult Sioux males agree. Standing Rock reduced to 2.4 million acres. Most good farmland is lost. The bill causes great dissention between signers and non-signers at Standing Rock.

Federal government outlawed butchering of rationed beef in public. The government deemed it offensive to Indian women and children. Standing Rock Agency complied by building slaughter-houses at issue stations.

Land surveys begin on Standing Rock in anticipation of break-up of Great Sioux Reservation. Sitting Bull and others protest to no avail.

Health is poor among Standing Rock Sioux. Agent reports deaths exceed births. Food rations cut sharply and Standing Rock agent reports many children and adults near starvation.

1889–1890

Severe drought strikes the Dakotas. Crops at Standing Rock are a total failure.

1890

December 15 — Sitting Bull, Hunkpapa, killed at home on Grand River by Indian police acting under government orders. Supporters and family of Sitting Bull are killed, as well as police.

December 29 — Massacre of over 300 Lakota at Wounded Knee, South Dakota, by the U.S. Seventh Cavalry.

1890s

Sioux begin to organize Black Hills Councils on their reservations for the purpose of seeking return of this sacred area. Standing Rock contingent is active in this effort.

1894

Gall dies. He was noted as a great warrior, particularly at the Little Bighorn. Later he became a judge in the Court of Indian Offenses. He is buried at St. Elizabeth’s Mission in Wakpala, South Dakota.

1903

Fort Yates military post abandoned; men sent to Fort McKeen; military graves relocated at this time.

1908

Town of McLaughlin established; named after Major James McLaughlin’s family.

1914

Sioux County organized on September 3; named after the non-Indian term Sioux Indians; county seat at Fort Yates; area 1,169 square miles.

Standing Rock men form a general council to represent the peoples’ needs and concerns to the government agent on the reservation.

1914–1918

Many Indian men throughout U.S. enlist in armed services to fight in World War I even though they are not citizens. Richard Blue Earth of Cannonball, North Dakota, was the first North Dakota Indian to enlist. Albert Grass, also from Cannonball, died in the war.

1915

Another wave of homesteading approved on Indian lands. Standing Rock Reservation opened to homesteaders May 13th. Ferry boat operating near Fort Yates, fare 25 cents to Mandan or Bismarck.

1919

Indians who served in the military during World War I are recognized as citizens of the United States and entitled to vote in federal elections.

1923

Black Hills claim is filed by Sioux Nation in U.S. Court of Claims.

1924

Snyder Act confers U.S. citizenship on all Indians.

1933–1936

Indian Civilian Conservation Corps active on reservations. Standing Rock Sioux contingent is active on the reservation planting gardens, stringing fences, building dams, etc. during the Great Depression.

1934

June 18 — Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) is passed, ending allotment, providing for limited tribal self-government, and launching the Indian credit program. Standing Rock did not adopt an IRA government.

1936

Sun dance at Little Eagle, South Dakota, on Standing Rock Sioux Reservation. Indian Reorganization Act permits greater religious freedoms for Indian people.

1937

Sun Dance at Cannonball, North Dakota, on the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation.

1940

U.S. government repeals act prohibiting the sale of alcoholic beverages to Indians.

1942

U.S. Court of Claims dismisses Black Hills Claim brought by Sioux Nation.

1946

August 1—Indian Claims Commission established to end Indian land claims by making monetary compensations. Black Hills claim can be re-filed.

1948

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers began construction of Oahe Dam (South Dakota). Despite intense opposition from Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, 160,889 acres of prime agricultural lands were flooded. Twenty-five percent of reservation population had to relocate out of flooded area.

1952

Indian Relocation Program established for all Indians. This program was part of the termination program initiated by the federal government. The government sought to end the reservation system and in preparation, relocated Indian families to urban areas.

1953

June 9 — U.S. Representative William Henry Harrison of Wyoming introduces House Concurrent Resolution 108, which states that Congress intends to “terminate” at the “earliest possible time” all Indians, meaning that Congress will no longer recognize individuals as Indian and will remove all Indian rights and benefits.

1968

April 11—American Indian Civil Rights Act passed, guaranteeing reservation residents many of the same civil rights and liberties in relation to federal and state authorities.

1973

The Standing Rock Sioux Tribal Council granted a charter creating Standing Rock Community College to operate as a post-secondary educational institution.

1974

Indian Claims Commission awards Sioux $17.5 million plus interest for taking of the Black Hills pending determination of government offsets.

1975

January 4—Congress passes the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act, expanding tribal control over reservation program and authorizing federal funds to build needed public school facilities on or near Indian reservations.

U.S. Court of Claims reverses Indian Claims Commission decision thereby removing monetary award from Black Hills Claims case.

1976

October 8 —Congress passes a bill to terminate the Indian Claims Commission at the end of 1978. The U.S. Court of Claims is to take over cases that the commission does not complete by December 31, 1978.

1978

Congress provides for new hearing in Black Hills Claim.

August 11—Congress passes the American Indian Religious Freedom Act (AIRFA), in which Congress recognizes its obligations to “protect and preserve for American Indians their inherent right of freedom to believe, express and exercise [their] traditional religions.” This reverses official government policy prohibiting the practice of Native American spirituality passed in 1883.

November 1—Congress passes the Education Amendments Act of 1978, giving substantial control of education programs to local Indian communities.

November 8—Congress passes the Indian Child Welfare Act, establishing U.S. policy to promote the stability and security of Indian tribes and families by giving tribal courts jurisdiction over Indian children living on or off the reservation.

1979

U.S. Court of Claims awards Sioux Nation $17.5 million plus interest for taking of the Black Hills.

1980

U.S. Supreme Court affirms Court of Claims ruling in Black Hills claim and awards Sioux $106 million. The court decries the taking of the illegal seizure of the Black Hills by the U.S. government, “A more ripe and rank case of dishonorable dealings will never, in all probability, be found in our history.” Sioux overwhelmingly reject money settlement in the Black Hills case and seek return of the land. Work on land return continues; no tribe has accepted any monetary compensation.

1988

Legislation enacted to repeal the 1953 termination policy established by House Concurrent Resolution 108.

1990

The Native American Grave Protection and Repatriation Act protects Indian gravesites on federal public lands against looting. The Indian Arts and Crafts Act, which goes into effect in 1996, finally protects the work of Indian artists, an effort that began in 1935.

1996

On March 6, the Standing Rock Sioux Tribal Council voted to officially amend the charter, changing the name of Standing Rock Community College to Sitting Bull College.

2001

The Kenel District rebuilds Fort Manuel Lisa and developed tourism in their community. Manuel Lisa built the Fort in 1811.

2004

The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe builds a multi-million dollar tribal headquarters building to house all the tribal government and employees.

2005

Highway 1806 on the Standing Rock Reservation becomes a national Native American Scenic Byway. The entire 86 miles of the Standing Rock Native American Scenic Byway are within the borders of the Standing Rock Reservation. In addition to its rich history, the reservation is unique due to its location in two states—North Dakota and South Dakota.