Introduction

The Lakota/Dakota people were the last to battle the United States government and surrender their homelands. Hence, it is these people who most often epitomize all American Indians. The image that most people have of an American Indian is either that of a stoic warrior sitting on a horse wearing a “warbonnet” and “warpaint,” or that of a beautiful “Indian princess” wearing braids and sitting in front of a tipi.

Today, we should know that this Hollywood stereotype of the Lakota/Dakota people is not only inaccurate but is also only one image of the many diverse American Indian nations across this continent. Each tribal nation had—and still has to some degree—their own manner of dress, their own type of dwelling, their own language, and their own customs and traditions. This section will briefly discuss some of the cultural lifeways of the Lakota/Dakota people.

Pre-Reservation Life

Although the migrations of the earliest Lakota/Dakota people are hazy, it is generally agreed that they were once a woodland people who made their homes east of the Missouri River. Warfare with other tribes and the advent of the horse, however, shifted and expanded their territory to the northern plains.

The introduction of the horse significantly changed and enhanced the entire lifestyle of the Lakota/Dakota people. Called “sunkawakan” or “mysterious dog,” the horse made it possible for the people to travel over a larger area, become adept raiders and warriors, and more effectively hunt the ever-roaming buffalo.

It would be difficult, indeed, to talk about the subsequent life of the Lakota/Dakota people without mentioning the importance of the buffalo. In fact, the lifestyle of the people depended upon and revolved around the buffalo. Campsites were chosen based partly on their relation to the buffalo herds, homes were made to accommodate the roaming of the buffalo and every part of the buffalo was used in some way. “Pte,” as the people called them, were the primary source of food, utensils, clothing, and homes.

Way of Living

The Lakota/Dakota people were the first to invent and own “mobile homes.” For the nomadic hunters of the plains, the portability of the tipi made it the ideal dwelling. Basically, the tipi consisted of several buffalo hides sewn together and wrapped around a conical frame of poles. A small tipi would take seven or eight hides to fit while a large, family tipi or council lodge could take up to eighteen hides.

In addition to portability, the shape of the dwelling was ideal for cold northern plains winters. Because of its conical shape, the air volume at the top of the lodge reduced the amount of heat required to warm the lower living space. In the summer months, the edges of the tipi could be rolled and tied up to allow the cool summer breezes to flow through the lodge.

While providing skins for tipi covers, the buffalo also provided skins for clothing. The Lakota/Dakota women wore mid-shin length dresses made of elk, deer or buffalo hides, knee-high leggings and moccasins. The Lakota/Dakota men wore a leather breechcloth and moccasins during the hot summer months. In the winter months, the men wore long buckskin leggings and a buckskin shirt. Both men and women also wore thick buffalo robes in winter.

Like most utilities in the Lakota/Dakota lifestyle, clothing and robes were decorated with either porcupine quills or paint derived from various plants or berries. Later, fur trappers and traders brought the quickly-adopted beads.

The buffalo provided more than clothing and shelter, though. Various parts of the buffalo provided everything from eating utensils to sewing thread. For example, buffalo bones were used for a myriad of items such as knives, arrowheads, fleshing tools, scrapers, awls, paintbrushes, toys, shovels, sleds, shovels, splints, and war clubs. The buffalo horns were used for such items as spoons, cups, ladles, and fire carriers. Even buffalo chips were used for fuel.

Although the buffalo was the primary food source for the Lakota/Dakota people, their diet was varied. Deer and other wild meat were also cooked with a variety of native plants, berries, roots, and herbs. For example, chokecherries and wild turnips were used in many different dishes. In addition, the people would either trade with, or raid, other tribes for agricultural items such as corn or beans.

Ways of Believing

"The Legend of the Pipe"

One day, two men were out hunting. Suddenly, a beautiful young woman stood before them. One hunter recognized that she was “wakan” (a mystery) but the other hunter saw only a beautiful woman and had lustful thoughts about her. This man was immediately enveloped in a cloud of smoke. When the smoke cleared, a pile of bones was left in the place where the man had stood.

The other hunter became very afraid but the woman reassured him. She told him that she came bearing a gift for the people and instructions for a good and sacred way of living. She told the hunter to return to his people and tell them to prepare for her to visit. The next day, the woman returned bearing the sacred pipe and instructed the people in the sacred ceremonies of the people.

After the woman instructed the people for four days, she left the pipe and walked away from the camp, making four transformations in appearance until she became a white buffalo calf.

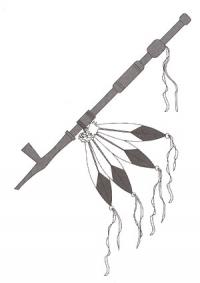

The legend of Ptesanwin, or White Buffalo Calf Woman, explains how the Lakota/Dakota people came by the sacred calf pipe and their most important ceremonies. This specific pipe, which is still kept to this day, is considered the most sacred possession of the Lakota/Dakota people. Pipes are used in ceremonial manner to represent truthfulness between those who smoke it. Because the pipe was used in meetings set up to resolve conflict between the Lakota/Dakota and the U.S. Army, it was often mistakenly called a “peace pipe.”

Ceremonies

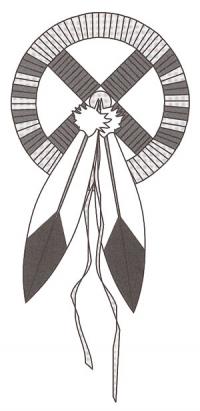

The ceremonies given to the Lakota/Dakota people have been maintained for hundreds of years. One of major importance to the Lakota/Dakota people is the Sun Dance. The Sun Dance is a sacred ceremony of prayer and sacrifice. It lasts approximately one week and involves piercing the skin of the breast, shoulders, or back.

The second ritual that is important to the Lakota/Dakota people is the “inipi” or sweatlodge ceremony. The sweatlodge is a willow frame-covered by buffalo skins. Inside, participants sing and pray while water is poured over hot rocks. The sweat is meant to cleanse and purify the mind and body.

Third, the becoming-woman ceremony celebrates the time when a young girl begins her menstrual cycle and officially becomes a woman.

Fourth, the “spirit keeping” ceremony keeps a deceased relative’s spirit for one year. After that time, it is “released” with a feast, give-away, and ceremony.

The fifth well-known Lakota/Dakota ceremony is the “hanbleca” or vision quest. In this ceremony, a young man goes upon a hill to fast and pray for a vision that will tell him the purpose of his life.

Sixth, the making-relative, or “hunka,” ceremony is used to adopt a non-blood relative and, finally seventh, the throwing of the ball ceremony is a symbolic “game” that showed thankfulness for life.

These ceremonies all contained elements of the traditional Lakota/Dakota values that were so important to living a good life.

Kinship

For the Lakota/Dakota people, the greatest responsibility of a human being was being a good relative. In a society that depended on social order and community cooperation to survive, the rules that governed behavior needed to be strict. In order to avoid friction within an extended family, one rule was to avoid certain relatives. A dutiful son-in-law, for example, avoided talking to, or about, his mother-in-law.

Being a relative also meant taking care of all of your relatives. For example, if a woman lost her husband to war or sickness, her husband’s brother would often take her into his home as a second wife. Children were raised with a wealth of relatives around to help guide them through life and, if any became orphans, they were quickly taken in by their relatives.

In light of the cultural emphasis on being a good relative, it should not be surprising that the Lakota/Dakota people viewed the world holistically. The people believed in the interdependence of all life forms. They believed that all living things—the four-legged, the two-legged, the winged, trees, and plants—were related. All of these were fashioned by the Creator for a specific purpose and therefore deserved respect.

The Lakota/Dakota people used, and continue to use, the phrase “mitakuye oyasin” (“we are all related” or “all my relations”) at the end of prayers to express this belief that all living things in this world are interconnected.

World View

The Lakota/Dakota people do not consider themselves to have a “religion” so much as a way of life. Prayers and spirituality were not separate from everyday life but were an integral part of each day and that activity. The word for God in the Lakota/Dakota language is “wakan tanka” meaning “great mystery.”

Some specific values that were/are significant to the Lakota/Dakota people include honesty, generosity, bravery, and respect for elders and children.

Honesty was a cornerstone of the culture. The people did not have respect for one who would lie and, outside of raiding in a war party it was unthinkable for one to steal from another. As the Lakota leader Lame Deer said, “Before our white brother came to civilize us, we had no jails. Therefore, we had no criminals. We had no locks or keys, and so we had no thieves. If a man was so poor that he had no horse, tipi, or blanket, someone gave him these things....”

Generosity was a greatly admired trait among the Lakota/Dakota people. In fact, a man’s status in his band or tribe was greatly determined by his generosity with others. A Lakota/Dakota ceremony called the “give-away” demonstrates the importance of generosity. Traditionally, when a family or family member was honored for some reason, a family would give-away gifts and possessions such as homes, robes, and moccasins. In addition, they would treat the entire camp to an elaborate feast.

Today, the give-away is still an important ceremony. Important occasions such as graduations or naming ceremonies are celebrated with a feast and the giving away of horses, blankets, linens, cloth goods, and money.

Another important cultural value was bravery. In fact, warriors in the traditional Lakota/Dakota society earned more respect for doing brave deeds, such as counting coup (striking an enemy with a coup stick or with a bare hand), than for killing another. The Lakota/Dakota also recognized the importance of elders and children. They believed that wisdom comes with age and so elders earned and deserved respect. In fact, another word used for God was “tunkasila,” which means grandfather. Children were called “wakan yeja” which means “sacred beings” and were never hit as means of punishment. Children were expected to learn by example and were reprimanded through shaming or teasing.

Impact of Reservations

The culture of the Lakota/Dakota people changed dramatically with the encroaching settlements. Traders brought rifles to replace bows and arrows, cloth to replace tanned buffalo skins, and iron kettles to replace traditional cooking methods. In addition, the constant skirmishes and wars between the people and the U. S. Army and the near-extermination of the buffalo took a heavy toll on the Lakota/Dakota way of life.

In the late 1800s government policy shifted from “removal” of American Indians to “assimilating” the American Indian people into the white society. This policy had a devastating effect on the Lakota/Dakota culture.

After the Lakota/Dakota people were relegated to reservations, the solution to the new “Indian problem” was to turn them into farmers and ranchers. Indian agents were appointed to oversee individual reservations and reform “their” Indians. The agents, who also served to undermine the traditional leadership of the Lakota/Dakota people, sought to do this by discouraging the “heathen” and “barbaric” cultural practices.

Soon, however, it seemed that discouragement was not enough. In 1883, Secretary of the Interior Henry M. Teller (with support from some Christian religious organizations) established what came to be known on Indian reservations as “courts of Indian offenses.” These offenses consisted of all public and private traditional religious and cultural activities such as the Sun Dance, give-aways, naming, and becoming-woman ceremonies. Although practicing their own cultural ways was considered criminal, many Lakota/Dakota people continued to hold their ceremonies and events in secrecy. While the people outwardly adopted the trappings of non-Indian life, such as the clothing and the log-cabin dwellings, they continued to live and teach the traditional Lakota/Dakota culture.

During this same time period, the philosophy was that the American Indian people would assimilate faster and more thoroughly by going to school. Thus began a most destructive experiment for the Lakota/Dakota culture—the boarding school. Colonel Richard Pratt, founder of the first Indian boarding school, revealed the prevalent attitude in his statement, “I believe in immersing the Indians in our civilization and when we get them under, holding them there until they are thoroughly soaked.” In addition to teaching another way of life, boarding schools also made it difficult for parents to teach their children their cultural lifeways since parents rarely saw their children.

Lakota/Dakota Culture Today

The Wacipi

Although the assimilation period had a great impact, the culture of the Lakota/Dakota people has endured and adapted. There are certain aspects of the culture that are lost or fragmented such as some specific ceremonies, stories, and bits of language. But the basic values that the Lakota/Dakota people lived by hundreds of years ago are still being taught today. One way that the American Indian culture survives today is through what the Lakota/Dakota people call the “wacipi,” more commonly known as a “pow-wow.” The wacipi celebration is a cultural and social event that is still very important as a means of sharing and perpetuating cultural values and beliefs.

Contrary to the belief that they are summer events, pow-wows are held throughout the year. Winter pow-wows are usually one day events held in a local gym or large community building. They are generally smaller than summer pow-wows with the majority of the participants coming from the local area.

The summer pow-wows last from three to five days on the weekends. Participants in the summer pow-wows usually include visitors from other communities, states, and countries who camp around the bowery (dance arena) throughout the weekend.

At a northern plains pow-wow, spectators will see six different types, or styles, of dancers. The men will dance traditional, fancy bustle, or grass. The women will dance traditional, fancy shawl, or jingle dress.

Although the pow-wow is an important cultural event, it is not the only one. Many Lakota/Dakota families still participate in a variety of important ceremonies such as namings, adoptions, the Sun Dance, and the sweatlodge.

The Lakota/Dakota culture and Native American cultures in general, have been experiencing a cultural “renaissance” in several ways. Families are now seeking tribal elders, asking them to teach about the old traditions. There is also a greater emphasis on learning and preserving the native languages. Further, some schools and social programs now include and emphasize the teaching of traditional cultural ceremonies such as the sweatlodge and traditional cultural values, such as generosity and being a relative.