During the last quarter of the 19th century, millions of immigrants from Europe arrived in the United States. Immigration was welcomed by leaders of industry who wanted more workers. Many Europeans lived on tiny farms of perhaps five or ten acres and chose to leave their homes in EuropeImmigrants came to the United States from Asia, too. Chinese, Japanese, Koreans, and Philipinos (mostly men) came to the U.S. to work. All Asians were denied citizenship in the 19th and early 20th century unless they were born in the United States. In the late 19th century, a few Asians came to North Dakota and found work here. Others passed through as workers on railroad construction crews. Although many ethnic groups are represented in North Dakota’s population, there were very few Italian, French (other than French Canadians), or Spanish immigrants. In addition to many immigrants from northern and eastern Europe, North Dakota also attracted a few Syrians, both Christian and Muslim. because they knew that there was land in the United States that they could purchase or claim under the various land laws. North Dakota attracted many of the immigrants who came to the United States for land.

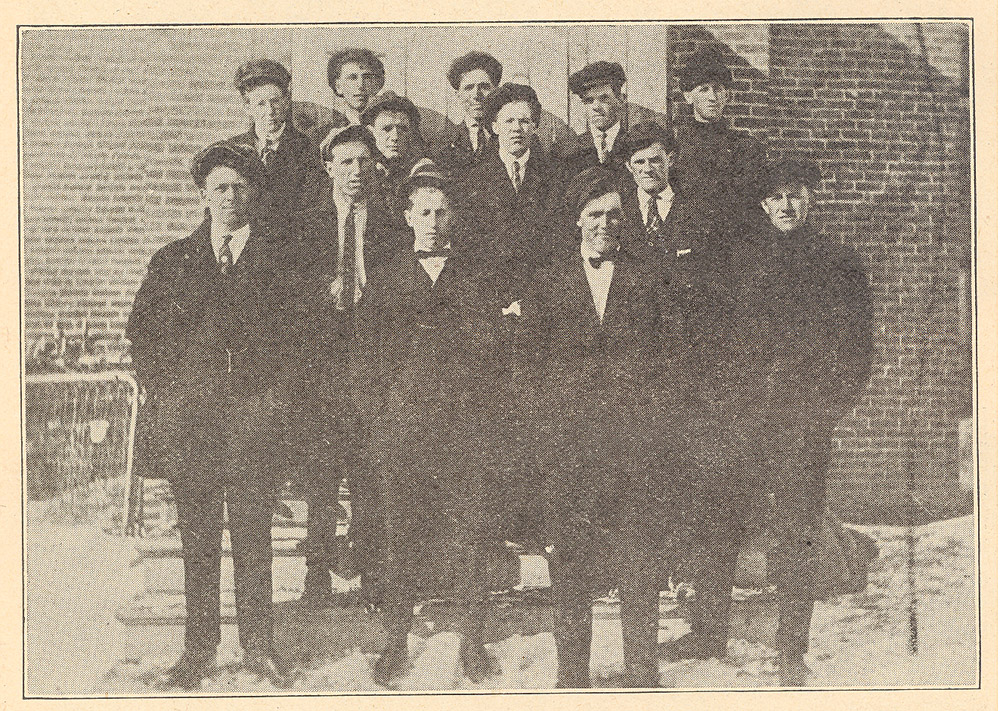

Across America, community leaders encouraged the immigrants to learn more about their adopted country. Concerned social workers and philanthropists set up settlement houses in cities. Perhaps the most famous of these was Hull House in Chicago. The settlement houses provided training in American housekeeping and childcare methods, English language, and citizenship. On the prairies of North Dakota, there were no settlement houses, but immigrants could study English and citizenship at their local schoolhouses. Schools for immigrants were sometimes called “America schools,” “night school,” or “evening school.” (See Image 13.)

The North Dakota legislature passed a law in 1917 supporting evening schools. The law stated that any county or city school district could organize an evening school for adults over the age of 16. If the school district did not set up an evening school, residents could request the district to establish a night school when at least 10 people were ready to sign up for instruction.

Though the law did not outline the course of study, most schools taught “topics and subjects that deal directly with the development of a high grade of American citizenship,” according to N. C. Macdonald, Superintendent of Public Instruction in 1918. Night schools usually included instruction in speaking, reading, and writing English. Students also studied American history and government.

The first year after the law was passed, 13 schools opened for evening classes. The state appropriated (budgeted) $7,000 for evening schools. Evening schools around the state enrolled 715 students in 1917.

One of the most accomplished students in North Dakota’s evening schools was Christina Hillius. (See Image 14.) Mrs. Hillius had emigrated from Bessarabia near the Black Sea in South Russia. Both Mrs. Hillius and her husband John spoke German. After they arrived in North Dakota in 1887, they established a farm. Later, Christina ran a hotel and restaurant in Kulm, while John operated several businesses. Though both Christina and John were successful in business and had learned to speak English, they had not learned to read and write in English. At the age of 60, Christina enrolled in evening school in Kulm. She was a model student and so successful in her studies, that the Department of Public Instruction included her picture in its publications. Schools often hung a picture of her in the classrooms to inspire younger students. The North Dakota Federation of Women’s Clubs sponsored a tour of the state featuring Mrs. Hillius as the main speaker.

In 1923, Christina Hillius spoke to the North Dakota Education Association. In her speech, she said that knowing how to read and write English improved her citizenship. When she voted, she was able to read and mark her ballot without help. Sometimes Mrs. Hillius shared the speaker’s platform with the state governor, or important visiting speakers. In 1924, Mrs. Hillius traveled to Washington, D.C. to speak to the National Education Association. Another speaking engagement took Mrs. Hillius to Denver in 1931 where she spoke to the World Federation of Education Associations.

Why is this important? In 1920, North Dakota had more immigrants than any other state except for New York. In 1920, immigrants and their children comprised about 70% of the state’s population.

Many immigrants settled in communities with others from their homelands. They did not have to learn English in order to get along. Some immigrants came from countries where they had not had the opportunity to attend school. In order for immigrants to fully participate in government they needed to speak, read, and write in English. Many immigrants believed they would have an advantage in business and politics if they spoke English as well as their native language.

In addition, families felt the need to learn English because that was the language their children spoke. As children learned English in school and spoke English with their friends, they began to lose the language of their parents. With a common language, families were able to communicate and enjoy spending time together.

Source: Fifteenth Biennial Report of the Superintendent of Public Instruction to the Governor of North Dakota, June 30, 1918; Iseminger, The Americanization of Christina Hillius.