A young Dakota boy growing up on the northern Great Plains in the middle of the 19th century learned the skills he needed as an adult from his parents and other men and women in the community. He learned to make bows and arrows and to hunt. He learned the ceremonies that would keep his family and community safe. He learned what an adult in his community had to know by practicing these skills as a child.

A young Dakota boy growing up on a reservation in North Dakota in 1900, learned what he would need to know as an adult by attending school. The school teachers were not his parents or other Dakota adults. The teachers were women, and a few men, who had excelled in school work and could teach their students to read, write, and do arithmetic. The boy would also learn a vocational skill such as boiler (heating system) maintenance. In fifty years, the educational needs of young Dakotas and other American Indian children had changed tremendously.

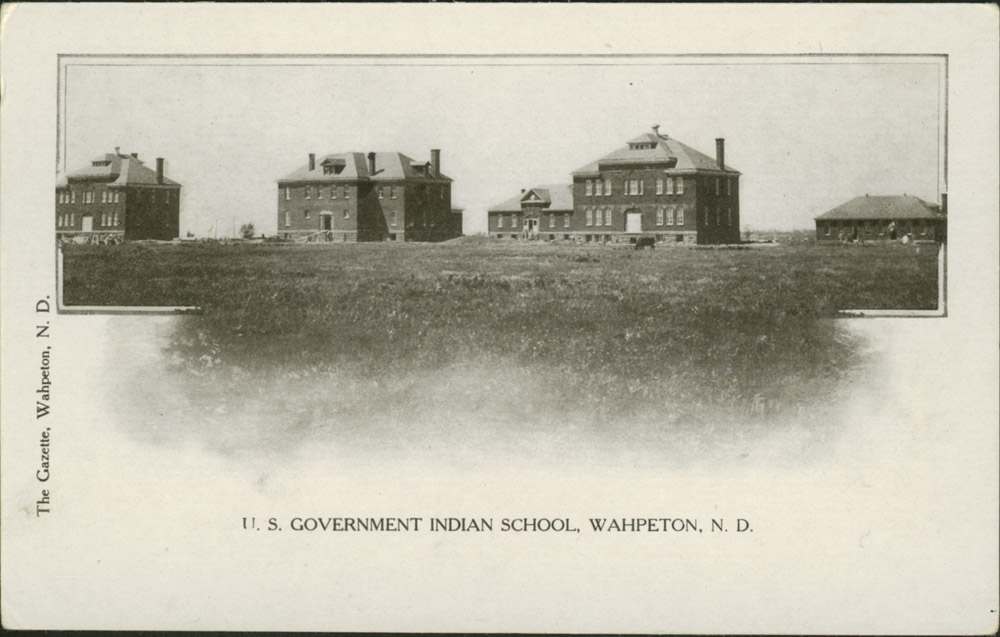

The parents of the Dakota boy did not attend school board meetings, or vote for the superintendent of schools. All of the decisions concerning schools on reservations were made by someone other than the parents. Missionaries ran the first schools. Later, federal agents established day schools and boarding schools. (See Image 6.) The curriculum (subjects of study) was partly academic and partly vocational.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, reservation schools and boarding schools (both federal and mission schools) had three goals. The first was to give the students a basic academic education in English. The second goal was to teach them vocational skills with which they might make a living as adults. These skills replaced skills that were no longer necessary on reservations, such as hunting, making a bow and arrows, drying and preserving bison meat. Schools supported the huge cultural changes American Indians experienced in the late 19th century. (See Image 7.)

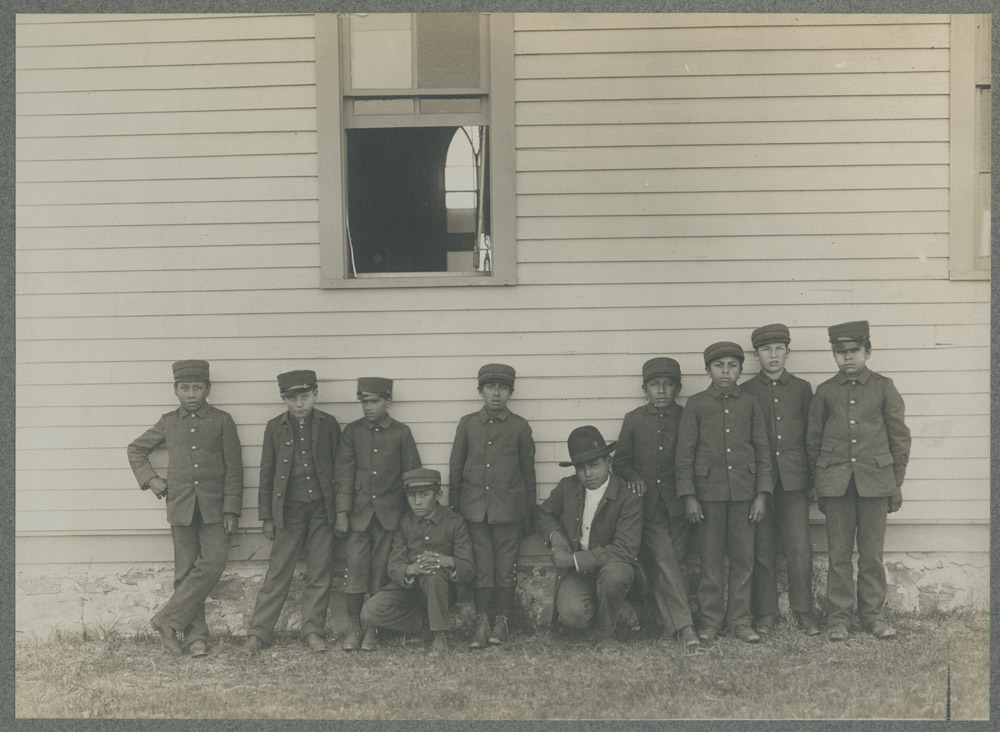

The third goal was the most difficult for many American Indian families. Most reservation and boarding schools intended to “kill the Indian to save the man.” This phrase, originally used by Captain Richard Pratt in the 1870s, embodied two contradictory ideas. Captain Pratt did not literally mean to kill Indians; he meant to save Indian people by putting an end to the wars between American Indians and the U.S. government. The educated Indian student would learn to live in the same manner as his non-Indian neighbors. (See Image 8.)

The other idea embedded in Captain Pratt’s phrase was the destruction of Indian cultureAssimilation means rejecting the characteristics of your own culture to accept the characteristics of a different culture. Cultural characteristics include language, clothing, hairstyle, songs, poetry, stories, religion, housing, and how one makes a living. Total assimilation means that a person has become so comfortable with the new culture, that he or she appears to have completely absorbed the new culture. Acculturation is a slightly different process. A person going through the acculturation process may accept some characteristics of another culture, but keep most of his or her own traditions. This person may be able to function culturally in two (or more) different cultures.

Many fur traders adopted some of the cultural traits of the tribes they lived and worked with. They were acculturated. Many American Indians adopted some characteristics of Anglo-American society including clothing, housing, and foods. Few American Indians assimilated to the degree that Captain Pratt and his followers would have liked. (“kill the Indian”). The children were taken from the love and instruction of their families and communities. When they arrived at a boarding school, the boys’ hair was cut and they were dressed in military style uniforms. The girls’ hair was fixed in a fashionable style (for non-Indians) and they were given dresses. The students’ moccasins were taken from them and they had to wear shoes. Teachers punished the students who spoke their native language. They were not raised to know and respect their families’ traditional religion and the ceremonies which fostered a strong and healthy community.

The schools were relatively successful in achieving these goals. However, the costs were high. Many students died at boarding schools. Students contracted diseases they had not encountered before and the disease travelled through the student dormitories quickly. Some students did not adapt well to school life and ran away. Some of the teachers were abusive. Many students returned home unable to communicate in their native language and felt that they had lost their place in tribal society.

However, many students regarded their school experience as largely positive. Those who successfully absorbed the lessons returned to their reservations with skills they used to improve the quality of life on the reservations. Some taught school, others took jobs with the reservation agency.

North Dakota’s reservations had both day schools and boarding schools. Many of the day schools were operated by missionaries until the 1920s. The Congregationalist missionaries at Fort Berthold, led by the Reverend Charles Hall, had two day schools on the reservation after 1876. At Standing Rock Reservation, Catholic missionaries opened a school for girls and a school for boys in the 1870s. Catholic missionaries opened both a day school and a boarding school at Turtle Mountain Reservation. The Grey Nuns, or Sisters of Charity, opened a day school and later taught in the federal boarding school at Fort Totten Reservation.

By 1902, there were 25 federal non-reservation Indian Boarding Schools in the United States including the Wahpeton Indian School (today called Circle of Nations School.) Most boarding schools followed the directive of Captain Richard Pratt to teach English, academic studies, and trade skills to young children who were separated from their parents and tribal communities.

Why is this important? Indian boarding schools were very different from the schools established in non-Indian communities. American Indian parents did not elect a school board and had little to say about what their children studied and how they were cared for in boarding schools. Non-Indian community schools were an important way to train students to participate in a democracy and to prepare them for a variety of life choices. Indian boarding schools were very different. Even though American Indian students studied government and civics courses, when they returned to the reservation, they had to prove through their use of their land allotments that they were entitled to citizenship.

Boarding schools led to major changes in reservation life. These changes were imposed on the tribes by the government. While some of the changes were good for individuals and led to significant improvements in reservation life (such as having Indian teachers in local day schools), the loss of traditional culture and family ties often led to disruptions in the personal and family life of some of the children who attended boarding schools.

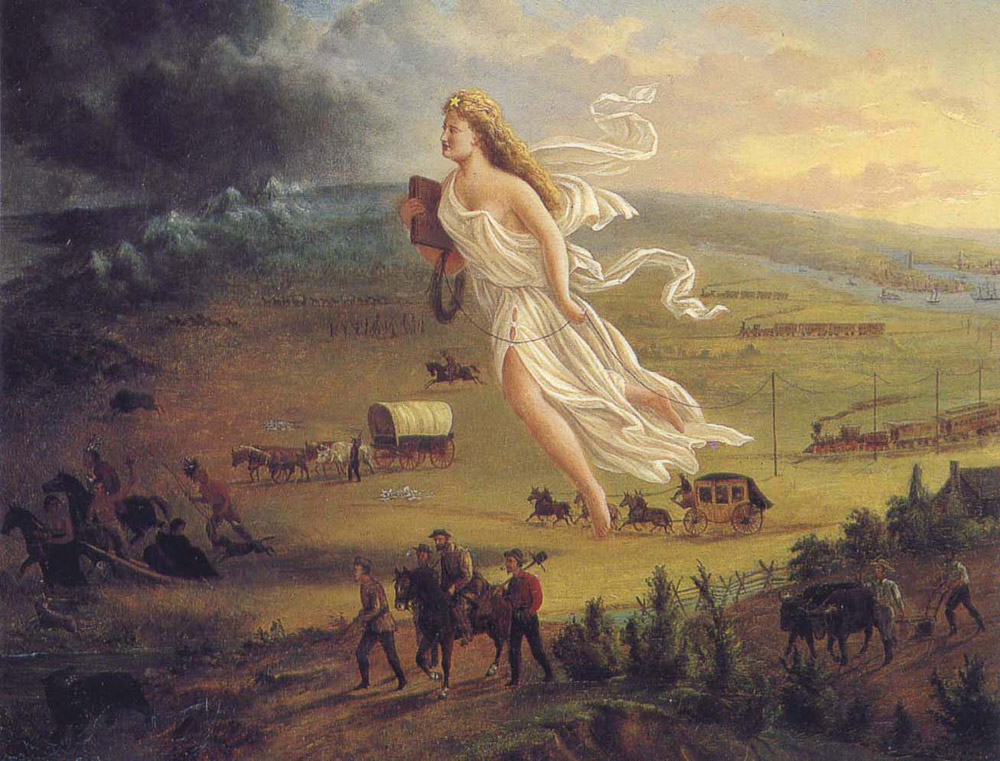

American Progress

This famous painting by John Gast was completed in 1872. (See Image 9.) It appeared on the eve of the centennial celebration of the United States (1876) when citizens were happy to see a strong message of progress. The original title was “Spirit of the Frontier.” It is better known today as “American Progress.”

Gast chose several symbols of American progress to tell his story. The woman, or angel, leads Americans toward Manifest Destiny. Manifest Destiny was a popular idea in the 19th century which justified American expansion across the continent. Those who believed in Manifest Destiny, which was almost all Americans, thought that God had destined the United States to bring civilization, democracy, and the virtues of education and capitalism to all of North America and, possibly, the entire world. The angel holds a telegraph wire in one hand. The wire represents technological progress that allowed the nation to expand across the continent. In her other hand, the angel holds a book representing the power of literacy and ideas in America’s growing strength.

The rising sun on the right side of the painting suggests that American culture and civilization is bringing light (representing knowledge and righteousness) from East to West. The east is bright and progress is symbolized by trains, farms, and cities engaged in business. The left side of the picture is dark. In the darkness we can see American Indian families leaving and their villages about to be overrun by trains and wagons. Bears, wolves, and bison also flee before “civilization,” represented by traders and miners in advance of farmers and cities.

This painting encompasses the ideas promoted by members of Congress, the Friends of the Indian, missionaries, and many federal Indian agents who believed that American Indians would prosper when they accepted the cultural values of the United States. They believed that education of the children was fundamental to cultural change.

Why is this important? The idea of American Progress and a belief in the special qualities of the American system of government and way of life were widespread in the 19th century. The idea of progress, also called Manifest Destiny, fueled expansion into North Dakota and the American West. American Progress justified the wars against Indians who resisted the power of the American government. This painting traveled around the United States to be displayed in cities and towns. It suggests that America held political, military, technological, and intellectual superiority over every other nation and culture.

Thomas Smith’s Letters from Hampton Industrial School

Thomas Smith was the son of Big Chief Woman, a Hidatsa, and Jefferson Smith, a European American trader and interpreter at Fort Berthold. Thomas was born in the mid-1860s. His Hidatsa name was No-watish which means In the Center. In 1878, Captain Richard Pratt visited the Fort Berthold Reservation to select students to attend Hampton Industrial School. With the help of the Reverend Charles Hall, the Congregational missionary at Fort Berthold, Captain Pratt selected 12 young people at Fort Berthold who could be expected to become leaders on the reservation after being educated at Hampton Industrial School. Thomas Smith was one of those students. Thomas studied at Hampton until 1881. His course of study focused on engineering as well as reading, writing, and speaking English. Courses included steam and gas pipe fitting and care of engines and boilers. He spent some time in the spring of 1881 working on a farm in Massachusetts.

When he returned to Fort Berthold, Thomas took a position in the agency farm. He was well-liked and the agent praised him as “earnest and economical.” Thomas also raised livestock and crops. He married and had a family of 10 children; one of his children attended Carlisle Indian School. Mr. Smith became active in Republican Party politics. Thomas Smith died in 1932.

All of the students at Hampton were required to write home regularly. They also wrote letters to donors who might help support the Hampton school. Here are two of his letters. The first was written to friends and family at Fort Berthold. The second letter was written to potential donors.

1: Letter to friends.

I am going to write this letter and tell what I learning in Engine-room now. These things that I had learned in there, and I only been in there five months now, so I don’t learn much yet, and I can running the engine, and I can pump water from the well to the tank, and I can pump water into the boiler when no water in boiler, and clean engine sometimes too. I can grease the engine, and I learn to make fires. I learn how to cut the pipes. I can run the engine and stop it again, and I like to work in there very much and learn something. And also I like to be a good engineer, and go back to my own home.

2: Letter, June 1887.

Dear Friend, I would like to write to you and tell you about myself. I don’t know anything when I first come to school because I never school at my own home. And I like going to school at Hampton better than my own home because I learn here more than at my own home. And I like to work, if I learn how to work. When I go home I think I must help some other Indians that don’t know anything about the white man’s ways or about the word of God. And I think it is best way to teach each other. And I know how to write but don’t know how to read yet. I know how to talk English but not much. And we are work every afternoon. So we like it very well. And school every morning. And we like it to learn a good way. We don’t want be a bad man. Because if we were bad God would not like that kind of man. So we want to be good. So we learn the white man’s way and we were past the Indians way about 100 years ago. And we take the new. All the Indians boys and gurls very well. And doing well. And we had very pleasant time last summer over Shell Bank. We had work out there and when we had done our work we used play out there. I wish to work out there again next summer. I heard that my Indians at my home learn something now. They don’t try to learn before I came here. And I am glad that they learn something now. And I wish that the Indian boys and girls come here to school and learn something for their people. Now our lesson in Arithmetic and reader. And English too. And I like to study them very much. And I been here two years. So I learn something new. But not much. And some of the Indian boys went over Mass[achusetts] last summer and went back here [a]gain last Oct. and they told us that them white people are good, because they are kind to the Indian boys and girls. That is all I have to say to you from your friend. Thomas Smith, or No-watish.

Source: James R. Young. “Thomas Smith: A Personal Pespective.” North Dakota History vol. 61, no. 2, (Spring 1994): 37-41.

Fort Totten Boarding School

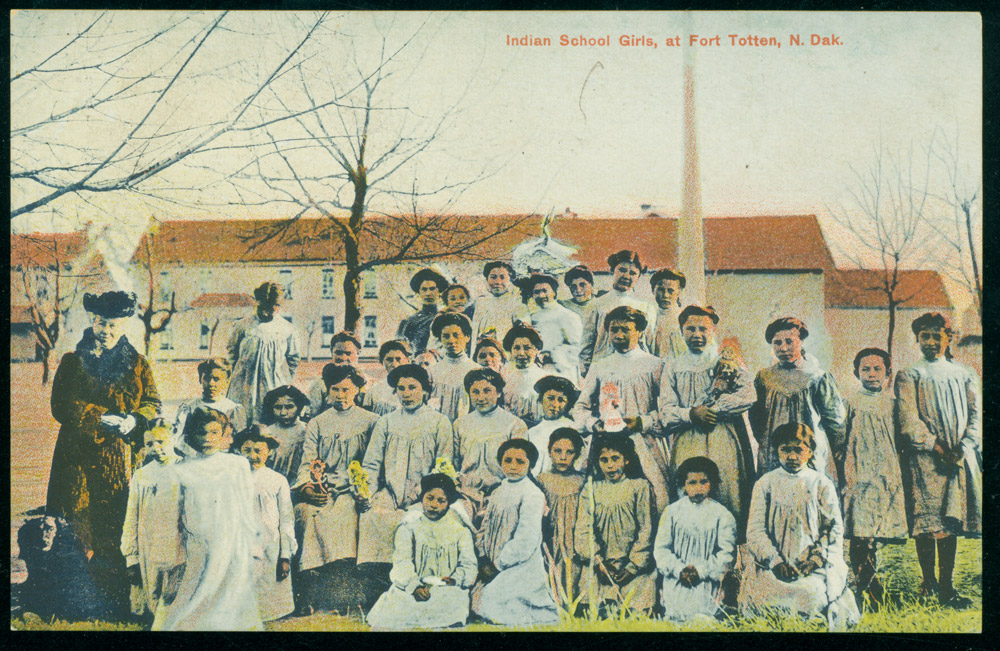

Students began to attend school at Fort Totten in 1875. Major William Forbes, the federal agent, invited the Grey Nuns of Montreal (in Canada) to come to the reservation to teach. The nuns spoke French. They needed an interpreter to communicate with students who spoke Dakota. The language of the school was English.

It was not unusual to have churches managing schools on reservations. The tradition of mission schools among American Indians was well established by the 17th century. Mission schools serving both American Indian and Métis children were located at Pembina in the 1850s. As part of President U. S. Grant’s Peace Policy, churches were assigned important roles at reservation agencies. The Catholic Church was assigned to teach and conduct Christian services on the Fort Totten reservation. Though the nuns were French Canadian, their job was to teach the children of the Fort Totten reservation how to speak, read, and write English, and other typical grammar school studies. Over the years, there were many complaints that the nuns’ command of English was inadequate and they did not speak Dakota. The nuns spoke to their students through an interpreter.

Dakota boys studied academic subjects, but also had training in vocational courses. Dakota girls learned how to keep house and cook in the style of European Americans. The nuns, like many of the “Friends of the Indian,” believed that practical training in domestic and industrial work encouraged the students to assimilate to Anglo-American ways. This training also gave students skills that could help them make a living on or off the reservation. (See Image 10.)

The sisters’ school, as it was called, was not popular at first. Children were encouraged, but not required to attend school. However, as enrollment increased, the school became overcrowded. Though there were some problems, many parents believed their children benefitted from the sisters’ school.

In 1891, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs chose Fort Totten as the site of a boarding school. The Grey Nuns were hired as teachers for the grammar school where students studied each morning. Academic courses included arithmetic, civil government, geography, spelling, history, English, and composition. (See Document 25.)

Document 25. A typical day at an Indian Boarding School.

Boarding schools for American Indian Children used a military model. Students wore uniforms similar to Army uniforms. Their days were carefully scheduled from the time they woke until they went to bed. Where “liberty” appeared on the schedule, the students had free time. Note the difference for “school detail” and “Industrial” students. “Tattoo” is a call to go to the dorms and get ready for bed. “Taps” is the end of the day. On a military post, these calls are made with a bugle. This is a sample day for a federal boarding school in the state of Washington.

Source: Cushman Indian School, Tacoma, Washington, February 1, 1912 Monday

5:45 A.M. Reveille.

5:55 to 6:10 Setting Up Exercise & Drill.

6:12 Air Beds.

6:12 to 6:45 Recreation.

6:45 First Call for Breakfast.

6:55 Assembly. Roll Call.

7:00 Breakfast.

7:30 to 7:35 Care of teeth.

7:35 to 7:40 Make beds.

7:40 to 7:55 Police Quarters.

7:55 Industrial Call.

8:00 Industrial work begins. School detail at liberty.

8:50 First School Call. Roll Call and Inspection.

9:00 School.

11:30 Recall. Pupils at liberty.

11:55 Assembly and Roll Call.

12:00 Dinner.

12:30 Recreation.

12:50 School and Industrial Call. Inspection.

1:00 P.M. Industrial work and School.

3:30 School dismissed. School detail at liberty.

4:30 Industrial recall. Drill and Gymnasium classes.

5:15 First Call.

5:25 Assembly. Roll Call.

5:30 Supper.

6:00 Care of teeth.

6:10 Recreation.

7:15 First Call.

7:25 Roll Call. Inspection.

7:30 Lecture. This period varies in length. Men prominent in education or civic affairs address the pupils.

8:15 Call to Quarters. Older pupils prepare lessons; intermediate children play.

8:45 Tattoo. Pupils retire.

8:55 Room check.

9:00 Taps.

The school also taught industrial (or vocational) training. Boys learned agriculture and livestock production. Later, the boys training included carpentry, masonry, plastering, and plumbing. These skills were necessary for the maintenance of the school buildings. Most of the building maintenance was done by the students under the direction of one of their instructors. Girls learned housekeeping. The girls were responsible for cleaning the buildings, washing the laundry, and cooking. (See Image 11.)

The Dakota and Chippewa residents of Fort Totten reservation did not approve of the way the school was managed. Discipline was harsh, the buildings were in poor condition, and the dorms were overcrowded. The children were often sick. Parents were not allowed to visit their children. Though the superintendent sometimes tried to be kind to the students, the supervising federal officials did not always support them. In 1906, Superintendent Charles Ziebach asked for funds to buy Christmas presents for each child in the school, but he was told there was no budget for gifts. He persisted and was finally granted permission to buy apples, nuts, and candy for the children, but the money to buy these gifts had to be raised from private donations.

By 1910, school discipline was more lenient. No longer were students required to march outdoors for hours in sub-zero temperatures as punishment for playing cards or smoking. Children were allowed to eat their meals with their brothers and sisters. Parents could visit their children. However, student labor was necessary to maintain the buildings and to do the farm work. Academic courses were neglected. A visiting inspector suggested in 1912 that students spend at least three hours a day on school work. The inspector also recommended that students in the first through third grade not be assigned to industrial work.

Lack of funding led to the closing of the school in 1917 for a few years. The school re-opened in 1919, but the school superintendent wanted to see Fort Totten students attend local schools in the county their parents lived in. The superintendent believed that the students would benefit from a good public education and that the schools would receive some federal funding for each Dakota child in the school. That plan did not work out, but the Fort Totten Indian Industrial School continued to educate students in academic courses and industrial skills until 1959.

Why is this important? Some school advocates believed that the students were gaining vocational skills that would be useful to them, but few buildings on the reservation, other than the school building, needed a mechanical engineer to run a heating plant. Except for farming and housekeeping, many of the skills the students learned were useless.

Some students had a good experience in boarding schools. They learned their lessons well and returned to their families and reservations with useful knowledge. Other students ran away, misbehaved, or in other ways showed their distress at being separated from their families and being disconnected from their culture.

The federal plan to educate Indian students succeeded as part of the “literary conquest” of American Indians. However, the cost to American Indian children included the loss of their language and culture, separation from parents, and the loss of skills that might have been useful on the reservation.

Health Care at Fort Totten School

At the Fort Totten Industrial School, Sister Auxelie Lajemmerais, was the only person to provide health care to students and other residents of Fort Totten Reservation. She was not trained in medical care; she used home remedies to treat illness. Later on, a doctor was hired to care for students and residents.

The health concerns were in some ways typical of any school. When one child came down with a cold, measles, or chicken pox, many other students contracted the disease, too. Other highly contagious diseases included conjunctivitis (“pink-eye”), and diarrhea.

Other health problems reveal the general condition of life on the reservation at this time. Residents often had respiratory diseases such as bronchitis and inflammation of the lungs. Tuberculosis (consumption) and meningitis appear often on the doctor’s record. There were no medicines to treat these diseases and they were usually fatal, though it might take years for tuberculosis to wear a person down. Many of these diseases are considered to be particularly prevalent among impoverished people and those who live in inadequate housing.

As a historic record, the doctor’s report provides another interesting detail about Fort Totten school. The children usually have English names while parents usually had traditional Dakota names. The parents may have been influenced by the school or missionaries when they named their children. On the other hand, the children may have received new names when they entered school.

Why is this important? School children’s health is a reflection of community health. Students with chronic diseases such as tuberculosis are likely to live with adults who also have chronic diseases. Though the schools helped to provide students with adequate meals, clean housing, and health care, the students’ families often lived in poverty. One measure of poverty is poor health. Few American Indians had experienced poverty and poor health before living on a reservation.