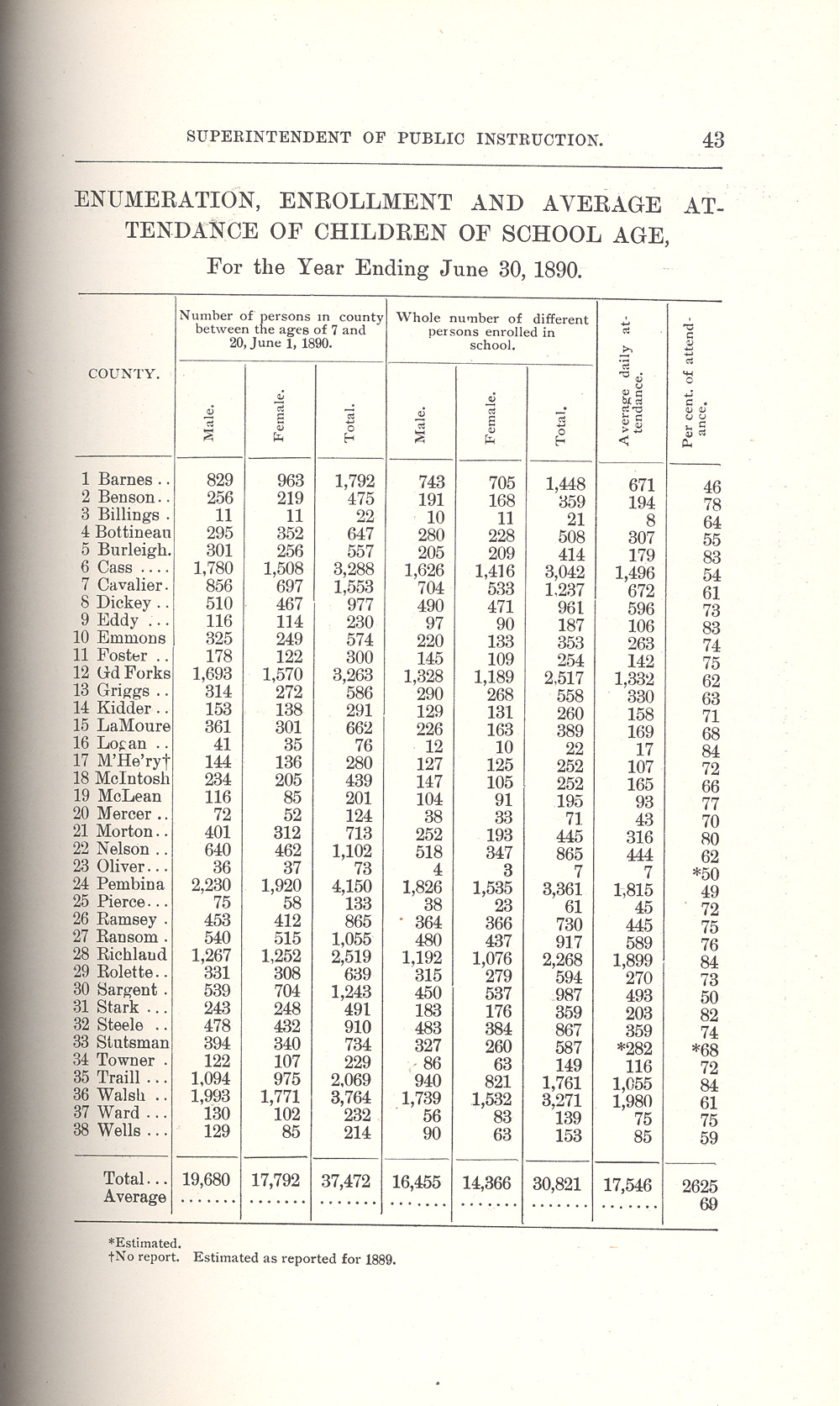

Official records tell us a lot about schools. For instance, in 1890, Logan County had one of the highest rates of attendance. (See Document 9.) On an average day, 84 per cent of the enrolled students showed up at school. However, if we read the record a little more closely, we also find that less than 30 per cent of the eligible children actually enrolled in school. The enrolled student was only slightly more likely to be male than female. (See Image 1.) In Traill County, the attendance rate was the same as in Logan County. In Logan County and the rest of the state, students were slightly more likely to be male than female. However, in Traill County, 85 per cent of the eligible students were enrolled in school.

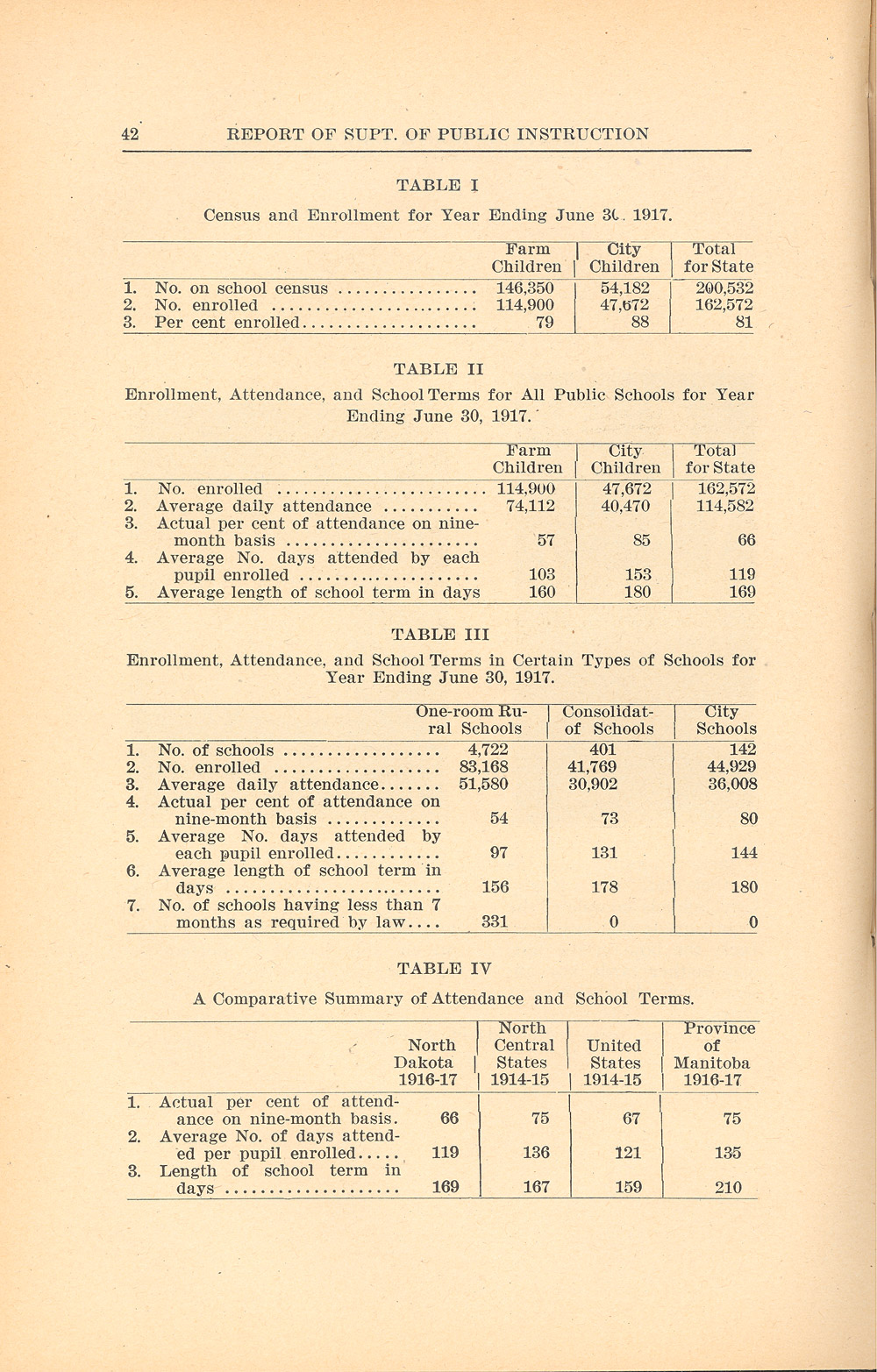

The 1917 school census shows that the population of school-age children had grown more than five times over the population of 1890. (See Document 10.) Average attendance had also increased considerably. These statistics also measure rural schools against urban schools. The numbers suggest that parents who lived in cities thought that their children would benefit from education. Rural parents may have wanted to see their children educated, but children were needed for farm labor which interfered with their education.

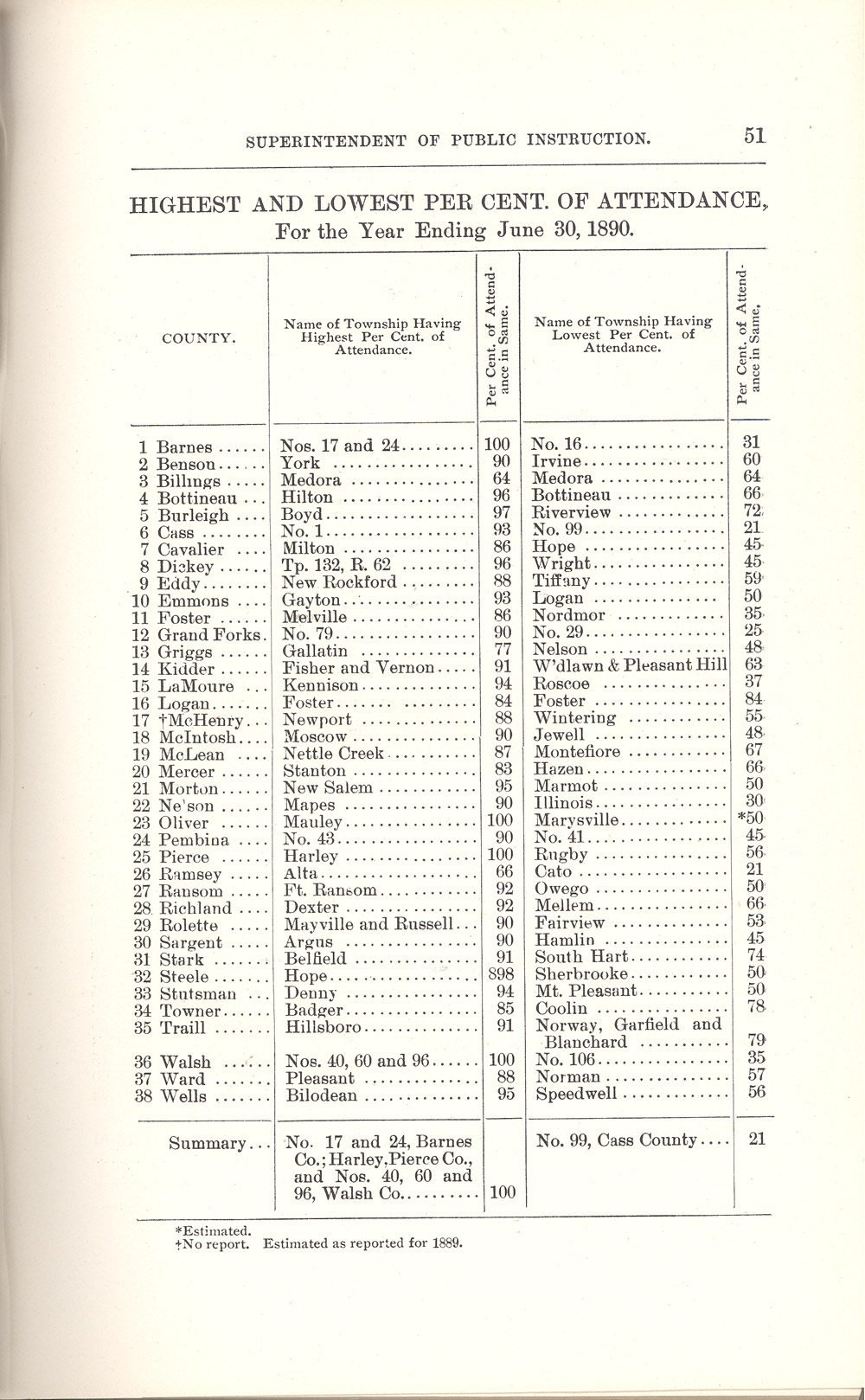

Few children went to school beyond the eighth grade, so it was important that their education be very thorough to that grade. (See Image 2.) The official eighth grade curriculum tells us that few new subjects were added in the eighth grade. Except for History and Civics, most of the lessons were continued from seventh grade. (See Document 11.) There were probably several reasons for this. Using the same textbooks saved money for the school district. Students who had reached the age of 14 in seventh grade were not required to attend eighth grade. The only subject these students would miss completely would be History. (See Image 3.)

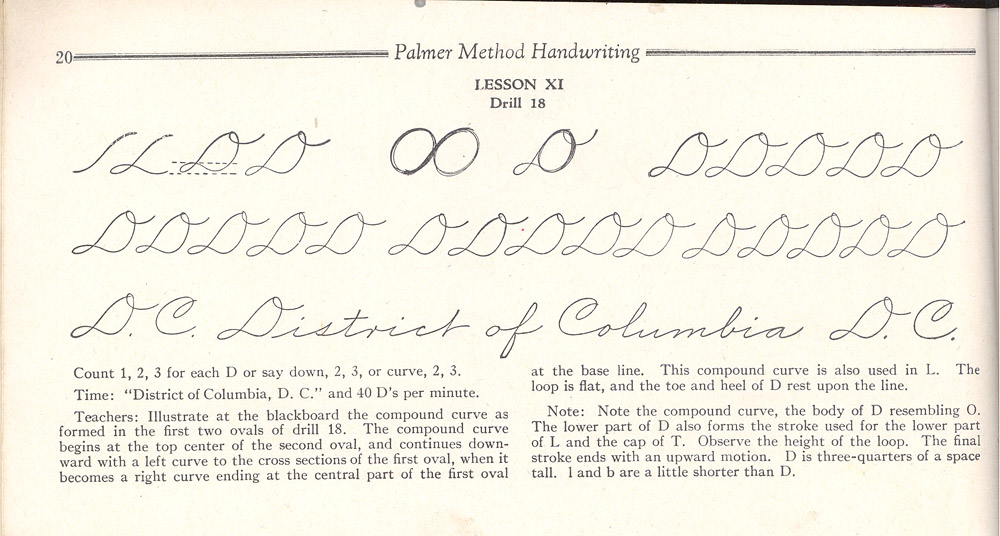

Perfect penmanship characterized the best students. From the second grade to the eighth grade, students practiced perfect penmanship. (See Document 12.) Those who succeeded in mastering penmanship could expect to get a good job as a clerk with a bank, an insurance company, or the railroad. All business records were kept by hand, so penmanship had to be legible and neat. Austin N. Palmer (1860-1927) developed a style of penmanship that allowed a writer to work for hours without tiring. He began to teach this style and published books on it. By 1912, the Palmer Method of penmanship instruction was common in schools throughout the United States.

School children who did not speak English had a difficult time in their first years at school. Entering schools meant mingling with children who spoke other languages and meeting a teacher who spoke English. Dakota Territory school law required English instruction in all schools, even if the school was in a district where all the residents spoke another language. Pauline Neher’s family spoke German. They had emigrated from South Russia in 1909 and settled on their homestead in western Mercer County in 1910. Pauline started school at the age of eight. She had been kept home until the law required her to attend school so that she could help her mother care for her younger brothers and sisters. (See Document 13.)

Document 13

Pauline Neher was sent to school a little later than many children. She had to stay home to help her mother with the younger children and the household work. Though she was a good student, she found school to be a terrifying place where she was punished for speaking German, the language of her parents.

I started school in September of 1919 and obviously had been indoctrinated into the German language. I knew very few English words, which was the case for the majority of pupils. . . .

During our noon hour, the teacher sat by an open window, crocheting away on a piece of lace, and listening for German talk. Ida Boehler and I were caught expressing ourselves in German. Each of us had to lie face down across the teacher’s desk. The repulsive teacher opened the underwear flaps and hit each of us on the bare-bottom with a stick. (page 88)

Some teachers did the children great good; others were an abomination to the emotional welfare of the children.

Take for example the inability to memorize arithmetic, spelling and readings! Grave punishment often with stick-and-whip thrashes were handed out, definitely in the form of abuse. Children’s mental states were beset with fear, therefore thwarted from learning. (page 91).

Aagot Raaen’s family spoke only Norwegian. (See Document 14.) Her parents had emigrated from Norway in 1869 and 1870. They met and married in Iowa and then moved to Steele County in northern Dakota Territory. The community around their home in Newburgh Township was settled almost exclusively by people from Hallingdal, Norway. There was no need to speak English, except at school. The two children in this excerpt are Aagot’s brother Tosten and sister Kjersti. A school teacher forced the children to change their Norwegian names to English names. Tosten accepted the name Thomas, but Aagot and Kjersti held onto their baptismal names.

Document 14

Aagot Raaen’s parents were Norwegian immigrants. They spoke Norsk (the language of Norway) at home and her mother never learned to speak English. Though school was fascinating with its promise of Americanization and all of its advantages, it was difficult to study when the rules were so strict.

An hour before school opened, dozens of children had assembled. So serious and quiet were they that they might have been mistaken for a crowd of dummies. All eyes were strained down the road to watch a moving speck. Yes, it must be the teacher. She came nearer and nearer. The children didn’t move; they only stared. When she was within a few feet of the door she stopped and said, ‘Good Morning, children.’

Just a few dared to rely, ‘Godmorgen.’ As she unlocked the door, she nodded her head and smiled.

Left alone, everyone looked at everyone else as if to say: ‘Have you ever seen anyone as beautiful? And dressed all in white-like an angel?’

When the teacher came to the door again, she was ringing a small bell. The children understood that they were to go in. They crowded into seats, most of them three in each. The teacher made a speech and wrote a long list of words on the board. Beata Mark, who had been to school in another district, understood English. At recess she tried to make the following points clear to the rest:

1. Anyone who whispers will stay after school

2. Anyone who laughs out loud will stay in at recess.

3. If you have to talk to anyone, raise your hand and say, ‘May I speak?’ If you are thirsty, say, ‘Please may I get a drink?’ If you have to go out, say, ‘Please may I leave the room?’ The ones who never ask these questions will get better marks than those who do.

4. Anyone who speaks Norwegian in the schoolhouse or anywhere near it will be punished.

. . . The school day began at nine in the morning and lasted till four in the afternoon, with fifteen minutes’ recess in the middle of the forenoon, an hour for lunch at noon, and ten minutes’ recess in the middle of the afternoon.

To sit still, in an unnatural position, on a hard bench, staring either at the blackboard or at a book, trying to learn a new language, was a hard task that made heads ache and limbs stiffen. On the way home from the first day in school, Kjersti and Tosten had very little to say to each other. In the evening they went to bed quietly without being told. . . . Beginners, large or small, who did not understand English were taught to read from a chart fastened on a tripod that stood in front of them.

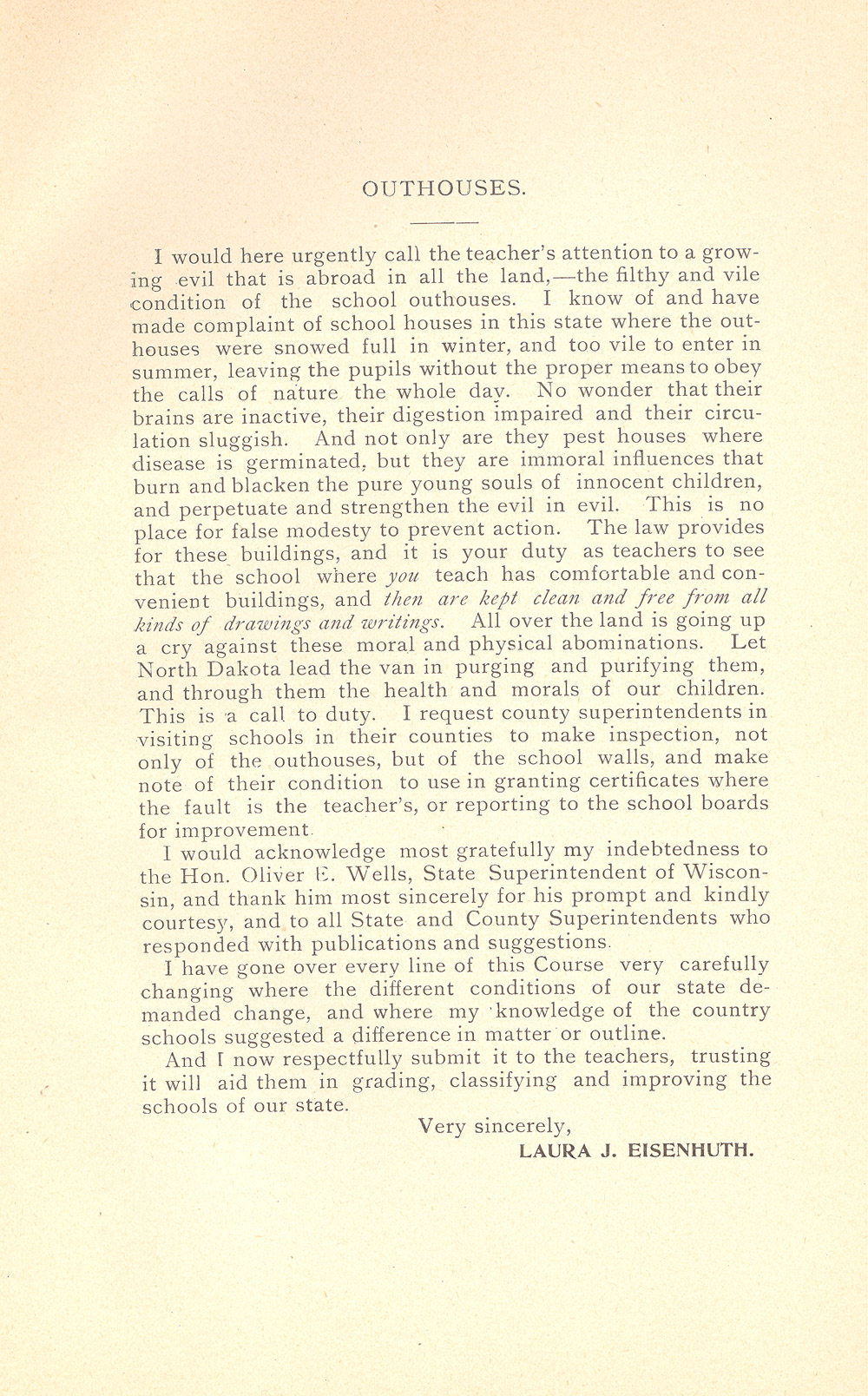

The universal experience for North Dakota school children was using the school outhouse. The ideal for the country school house was two outhouses: one for girls and one for boys. The outhouse might have two holes, or two seats, so that two children could use the outhouse at the same time. Many schools, however, had a single, one-seat outhouse that had to serve the teacher and students and whoever else came by the school to visit.

The school board was usually responsible for maintaining the outhouse in good condition. The teacher was responsible for cleaning the outhouse, a job that most teachers were reluctant to do. As a result, outhouses tended to be in filthy and in bad repair.

Most school superintendents overlooked the necessary evil that was the school outhouse, but Laura Eisenhuth, (See Document 15.) the first woman to be elected state Superintendent of Public Instruction, chastised schools for their lack of sanitation in the Report of the Superintendent of Public Instruction (1894) to the Governor.

LaRoy Bobzien, who taught in country schools long after Mrs. Eisenhuth had left state office, tells us that few school boards took Mrs. Eisenhuth seriously. (See Document 16.) He apparently put some thought into maintaining social order (if not sanitation) at his school with strict rules about who could use the outhouse.

Document 16

LaRoy Bobzien was a teacher in rural schools. Years later, he remembered the inadequate outdoor bathrooms that his students had to use.

“Since there was only one outdoor toilet to accommodate us all some ground rules were necessary. Because our little moon-in-the-door outhouse was in poor shape, the door and the hinges were ‘kaput,’ and because it accommodated only two people, the following rules for its use applied: only the girls used it, no less than two and no more than three girls were to use it at the same time, two girls could utilize the services and one girl held the door in place and kept it shut.

The facility the boys and I used was a small three- to four-stall barn. The dozen boys felt comfortable with it because that was what they used at home most of the time. . . .”