Life at Standing Rock was difficult. The government expected the Lakotas to take up farming, build log cabins, and live on their own farms apart from their friends and families. Some agents were corrupt and did not distribute rations properly. Even if they had been allowed to hunt, the buffalo had disappeared from Dakota Territory by 1883. Disease and hunger constantly diminished the population.

In 1889, the Great Sioux Reservation was broken up into four smaller reservations. The Lakotas had lost thousands of acres with the new reservation treaty. During the winter of 1889-1890, whooping cough, measles, and influenza struck the reservation causing more deaths, especially among babies and elders.

Then, in the spring of 1890, the people of Standing Rock learned of a new religion. The Ghost Dance, as it was called, had started in Nevada, but was spreading to Indian tribes all over the West. In October, 1890, Sitting Bull invited Kicking Bear, an Oglala Lakota from Pine Ridge Reservation, to come to Standing Rock to teach the Ghost Dance to the Hunkpapas. The Lakotas welcomed the hope and inspiration the religion brought to them. (See Image 12) However, non-Indians living near reservations became fearful about the new religion which promised that the buffalo would return and that Indian peoples would once again become powerful. Non-Indians did not understand that the Ghost Dance was a peaceful religion; nor did they understand how important it was for the Lakotas to hope for a better future. Non-Indians often called the Ghost Dance the Messiah Craze. (See Images 13 and 14.)

Politicians, federal reservation agents, and townspeople began to demand that the federal government take action to stop the Ghost Dance. President Benjamin Harrison asked the Army to investigate the Ghost Dance at Standing Rock. Sitting Bull was still considered the most powerful leader of the Standing Rock Lakotas. Major James McLaughlin, the agent at Standing Rock, agreed that if Sitting Bull were not on the reservation, the people would no longer follow the Ghost Dance.

In November, the Commissioner of Indian Affairs asked the Army to restore order on the Sioux reservations. Most of the military strength was focused on Pine Ridge and Rosebud reservations. The military presence and the threat of attack caused some people to stop dancing.

The Army and the Commissioner of Indian Affairs were still quarreling about authority on the reservations. During the Ghost Dance, the Army gained authority over reservations. General Nelson Miles, who had fought Sitting Bull in 1877, sent Buffalo Bill Cody to convince Sitting Bull to surrender. Agent McLaughlin sent Cody away before he could do so. General Miles was increasingly fearful that the Ghost Dance would result in an uprising. Miles ordered the arrest of Sitting Bull.

Early in the morning of December 15, Agent McLaughlin sent 40 Indian policemen to Sitting Bull’s cabin. (See Image 15.) Soldiers waited nearby to help if necessary. The policemen woke Sitting Bull and told him they would take him to the agency. Sitting Bull dressed and the men left the house. Outside the cabin, a large crowd had gathered. (See Image 17) The people urged Sitting Bull to resist. Sitting Bull stopped walking and refused to move further.

The Indian police, led by Lieutenant Bull Head, pushed Sitting Bull along. (See Image 18) People became anxious. Someone, perhaps Catch the Bear, fired a shot that struck Lt. Bull Head in the side. (See Document 3) As Bull Head fell, he fired his gun and the shot hit Sitting Bull in the chest. There was more firing and others were killed or wounded. Behind Sitting Bull, Sergeant Red Tomahawk fired his gun. (See Image 16) The bullet hit Sitting Bull in the head. The great wise and holy man of the Hunkpapas died. (See Document 4)

On the day Sitting Bull died, another respected spiritual leader named Big Foot, a Minneconjou Lakota of the Cheyenne River agency, started on a journey to help bring peace to the people of Pine Ridge. He traveled with a group of about 350 people, including a few who had fled Sitting Bull’s camp. (See Image 17) General Miles ordered soldiers to arrest Big Foot. For almost two weeks, Big Foot’s band continued on, avoiding the Army. The Minneconjous did not understand why the Army was after them. The soldiers mistakenly believed that Big Foot might cause more problems at Pine Ridge.

Finally, the Army stopped the Minneconjous and escorted them to a place on the Pine Ridge Reservation called Wounded Knee Creek. On December 29, 1890, the Army attempted to take weapons from the Minneconjous. A few resisted being disarmed. A shot was fired by a person unknown to us. Soldiers then opened fire. At least 150 Minneconjou men, women, and children died (some historians say perhaps as many as 300 were killed or wounded) including Big Foot. Twenty-five soldiers died and 39 were wounded. The massacre at Wounded Knee was the last armed encounter between the Lakotas and the U. S. Army.

Why is this important? The Ghost Dance was a religion of peace that brought hope to the Lakotas, but the Army, townspeople, and settlers still distrusted the Lakotas. The Army acted out of fear; the Lakotas responded in fear and confusion. Poor communication, struggles for power between the Army and the Indian Affairs office, and starvation and disease among the Lakotas fed the fear and confusion that contributed to the conflict. The Army’s only solution to the strife was to isolate the leader and prepare for a violent response.

The Indian police played an important role in the death of Sitting Bull. In the Lakota tradition, there had been a group of men who enforced the rules the tribe had agreed upon. Many Lakotas and Yanktonais had taken up policing in that tradition. The Indian police intended to carry out their orders to arrest Sitting Bull as peacefully as possible though they expected and were prepared for violence. The policemen who were killed at Sitting Bull’s cabin were honored with a grand funeral. [photo: 0739-v1-p41e] Sitting Bull was buried quietly without ceremony. The exact location of Sitting Bull’s grave remains a mystery.

Document 3

Sitting Bull died on Monday morning, December 15, 1890. He was nearly 60 years old. He died while trying to assert his power as a Lakota warrior and holy man and leader of his people.

Sitting Bull led a relatively quiet life after moving to Standing Rock in 1883. However, when the Ghost Dance – or Messiah Craze – came to Standing Rock, he and his followers took an interest in the religion. The Army and the Indian agents on the four Lakota reservations became more and more concerned about the power of the Ghost Dance among the Lakotas. The Indian Commissioner, Agent McLaughlin at Standing Rock, and the Army all agreed that if Sitting Bull were no longer leading the Ghost Dancers, the religion might simply fade away.

The Army ordered McLaughlin to arrange for Sitting Bull to be “secured,” or arrested. McLaughlin wanted to pick the date carefully to avoid possible conflict. McLaughlin suggested making the arrest on the day when rations (food) was being distributed at agency headquarters. On that day, few of Sitting Bull’s followers would be in their camp near his log cabin on the Grand River.

These documents and pictographs reveal details about the arrest and death of Sitting Bull. Some of the details do not match exactly which presents the problem that historians constantly have to deal with. Everyone who saw an event, saw it from a different angle. Perhaps the witness combines what he saw with what he heard from others. Perhaps over time, the witness forgot some of the details. Historians have to look carefully at documents to determine how accurate they are.

Another problem that documents present is how the attitude of the witness or the person reporting the event affects the readers’ ideas. Reporters and historians of the 19th and 20th centuries allowed their own attitudes about race and religion to influence the way they re-told the historical events.

The following paragraphs have been excerpted from some documents about the death of Sitting Bull. Copies of the full documents are attached. See also the pictographs by which Lakota witnesses to the event recorded their views.

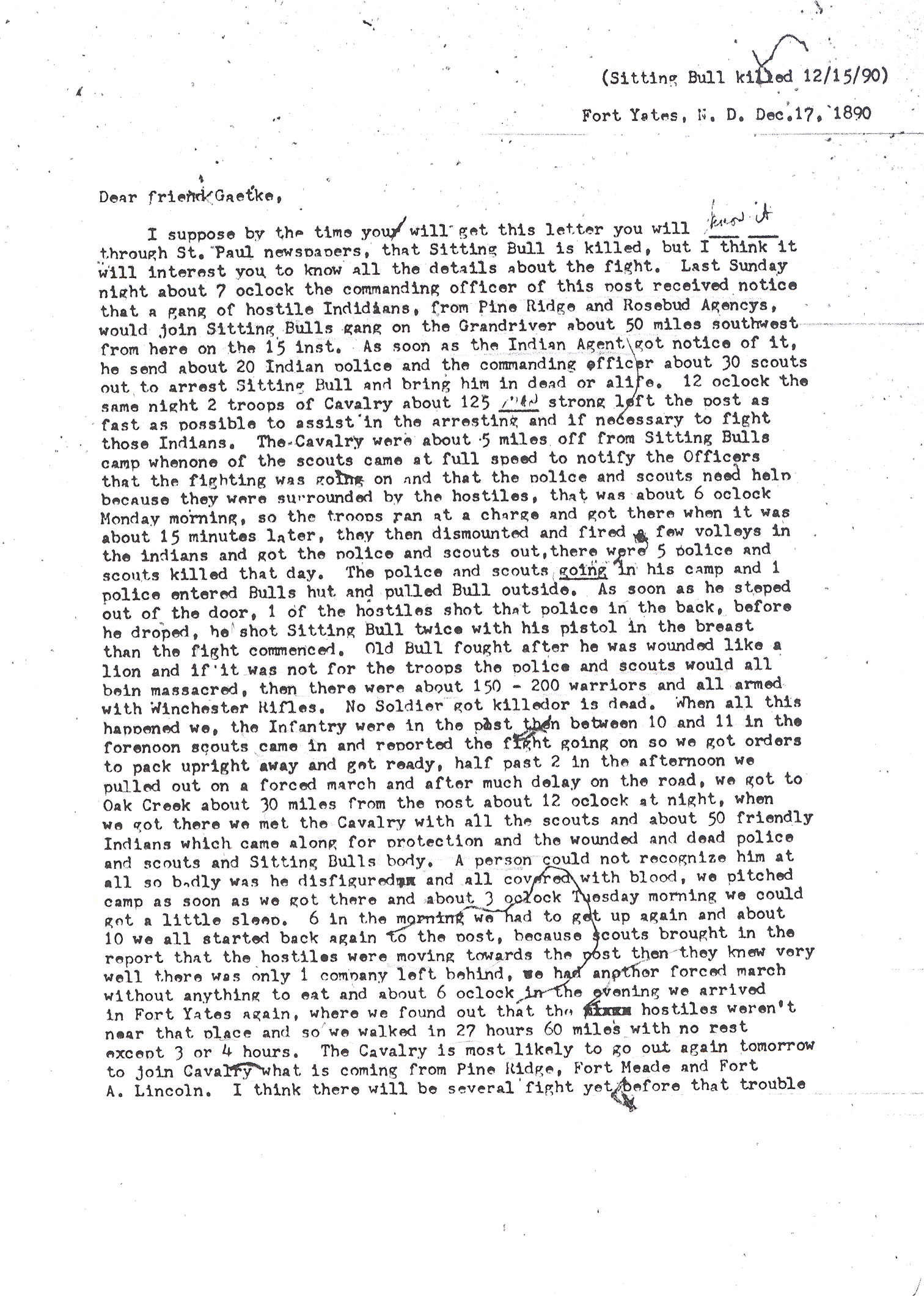

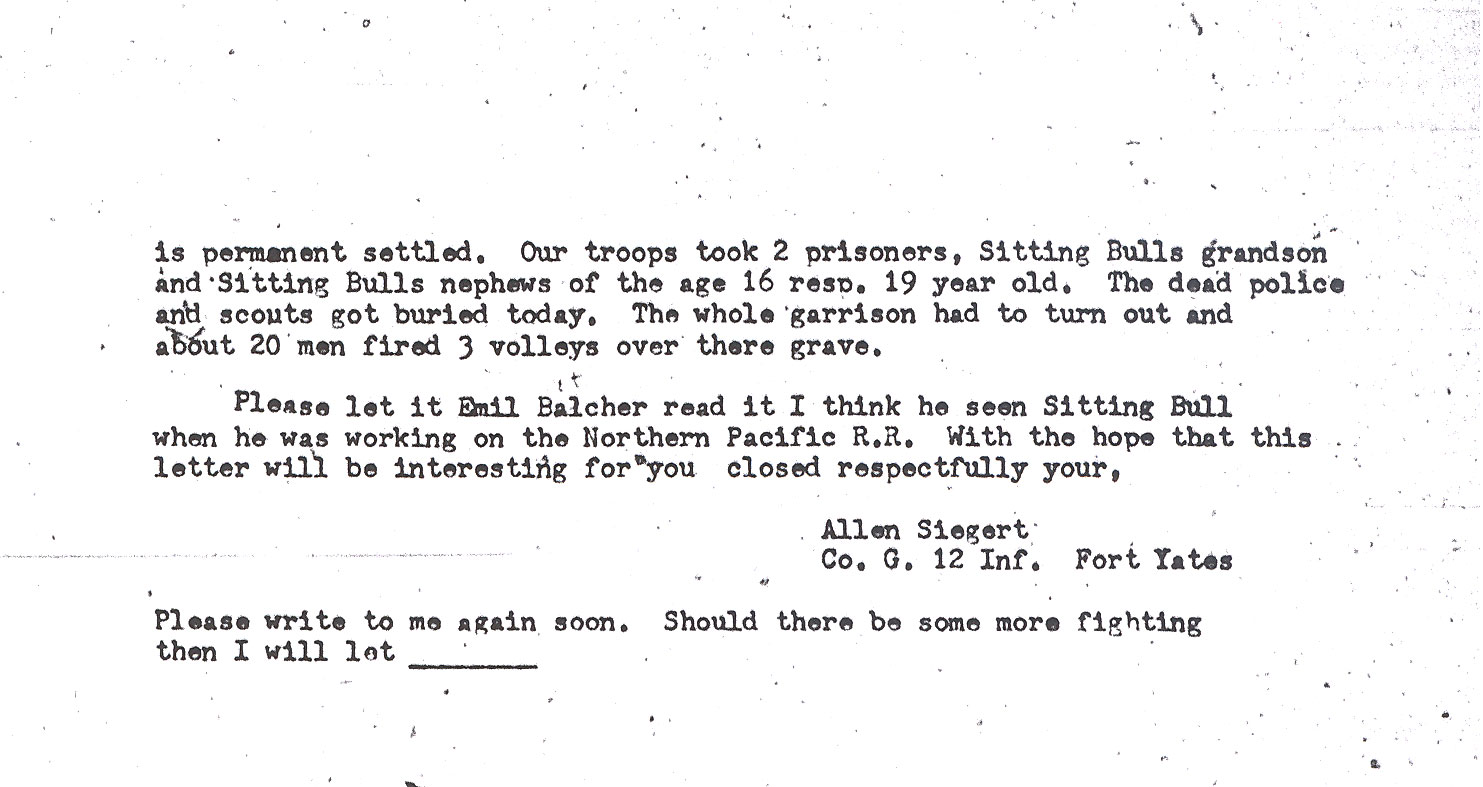

December 17, 1890. Allen Siegert wrote to his friend Gaetke two days after Sitting Bull was killed. Though he wrote immediately, and had access to information from witnesses, his facts are often incorrect.

“As soon as he [Sitting Bull] stepped out of the door, 1 of the hostiles shot that police [Bull Head] in the back, before he droped, he shot Sitting Bull twice with his pistol in the breast then the fight commenced. Old Bull fought after he was wounded like a lion and if it was not for the troops the police and scouts would all been massacred, then there were about 150 – 200 warriors and all armed with Winchester Rifles.”

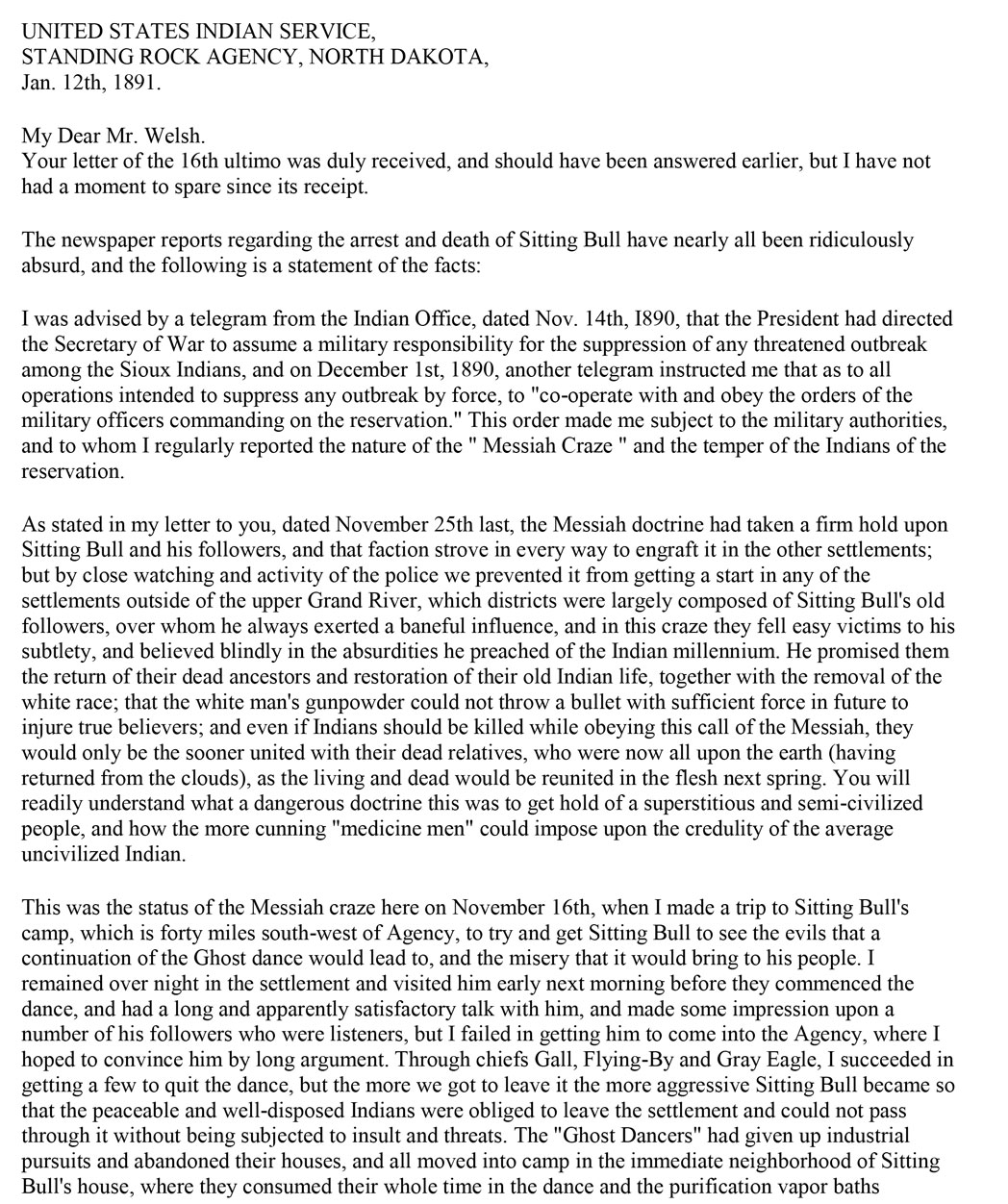

January 12, 1891. Agent James McLaughlin, Standing Rock to Herbert Welsh, Corresponding Secretary, Indian Rights Association.

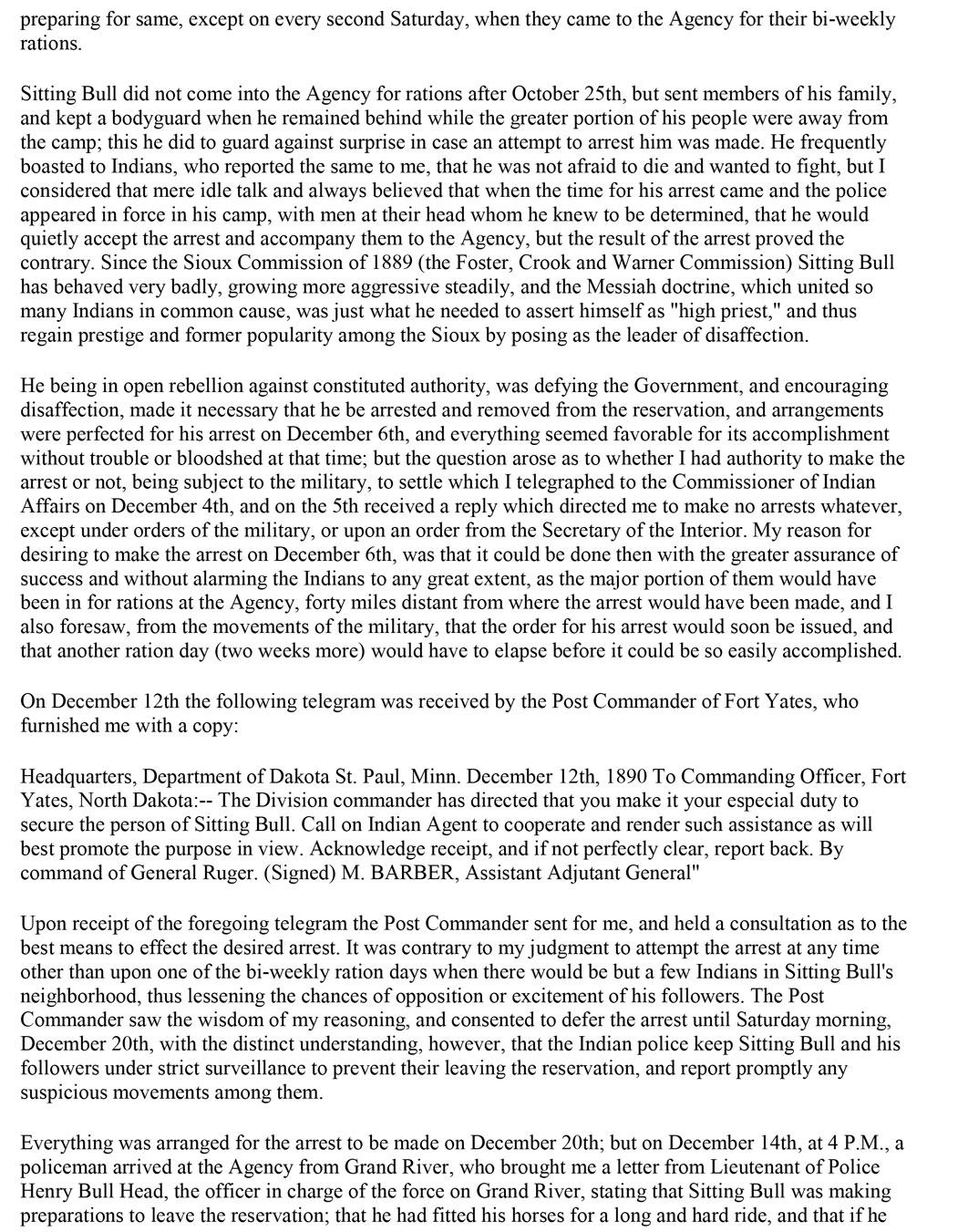

“[Sitting Bull] being in open rebellion against constituted authority, was defying the Government, and encouraging disaffection, made it necessary that he be arrested and removed from the reservation, and arrangements were perfected for his arrest on December 6th. . .”

“Everything was arranged for the arrest to be made on December 20th; but on December 14th, at 4 P.M., a policeman arrived at the Agency from Grand River, who brought me a letter from Lieutenant of Police Henry Bull Head, the officer in charge of the force on Grand River, stating that Sitting Bull was making preparations to leave the reservation; that he had fitted his horses for a long and hard ride, and that if he got the start of them, he being well mounted, the police would be unable to overtake him, and he, therefore, wanted permission to make the arrest at once.”

“ . . . immediate action was then decided upon, the plan being for the police to make the arrest at break of day the following morning, and two troops of the 8th Cavalry to leave the post at midnight, with orders to proceed on the road to Grand River until they met the police with their prisoner, whom they were to escort back to the post; they would thus be within supporting distance of the police, if necessary, and prevent any attempted rescue of Sitting Bull by his followers.”

“Sitting Bull accepted his arrest quietly at first, and commenced dressing for the journey to the Agency, during which ceremony (which consumed considerable time) his son, "Crow Foot," who was in the house, commenced berating his father for accepting the arrest and consenting to go with the police; whereupon he (Sitting Bull) got stubborn and refused to accompany them.”

“By this time [Sitting Bull] was fully dressed, and the policemen took him out of the house; but, upon getting outside, they found themselves completely surrounded by Sitting Bull's followers, all armed and excited. The policemen reasoned with the crowd, gradually forcing them back, thus increasing the open circle considerably; but Sitting Bull kept calling upon his followers to rescue him from the police; that if the two principal men, "Bull Head" and "Shave Head," were killed the others would run away, and he finally called out for them to commence the attack, whereupon "Catch the Bear" and "Strike the Kettle," two of Sitting Bull's men, dashed through the crowd and fired.”

“This conflict, which cost so many lives, is much to be regretted, yet the good resulting therefrom can scarcely be overestimated, as it has effectually eradicated all seeds of disaffection sown by the Messiah Craze among the Indians of this Agency, and has also demonstrated to the people of the country the fidelity and loyalty of the Indian police in maintaining law and order on the reservation.”

December 29, 1927. Frank Fiske article, Sioux County Pioneer. (Fiske was a long time non-Indian resident of Fort Yates)

“Bull Head, Shave Head and Red Tomahawk were the ranking members of the police force, and they were bringing Sitting Bull from his cabin when they were attacked by nearly two-hundred hostile Sioux. Bull Head and Shave Head fell at the first shot, but as he went down Bull Head fired into Sitting Bull's side. Red Tomahawk was directly behind the group and carried a small revolver that he had taken from the chief. With this he shot Sitting Bull in the head. Thus Red Tomahawk is given the credit for killing the most famous of Sioux Chiefs, and ending for all time the long standing warfare between the Indians and the white people. “

Document 4

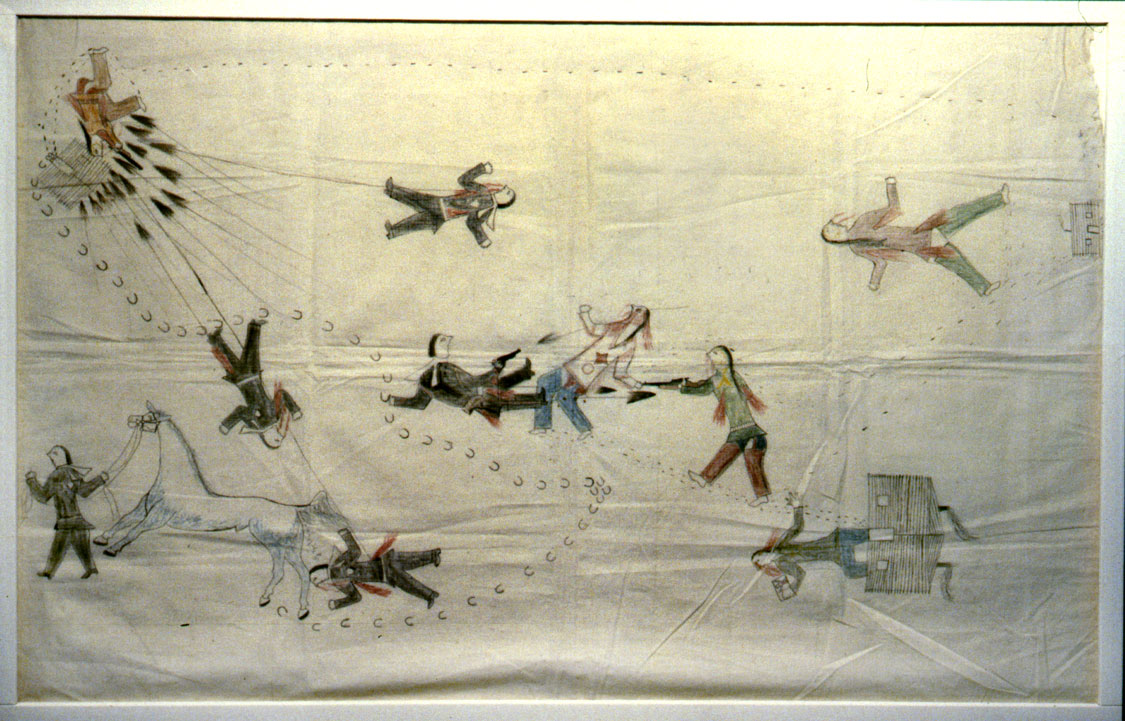

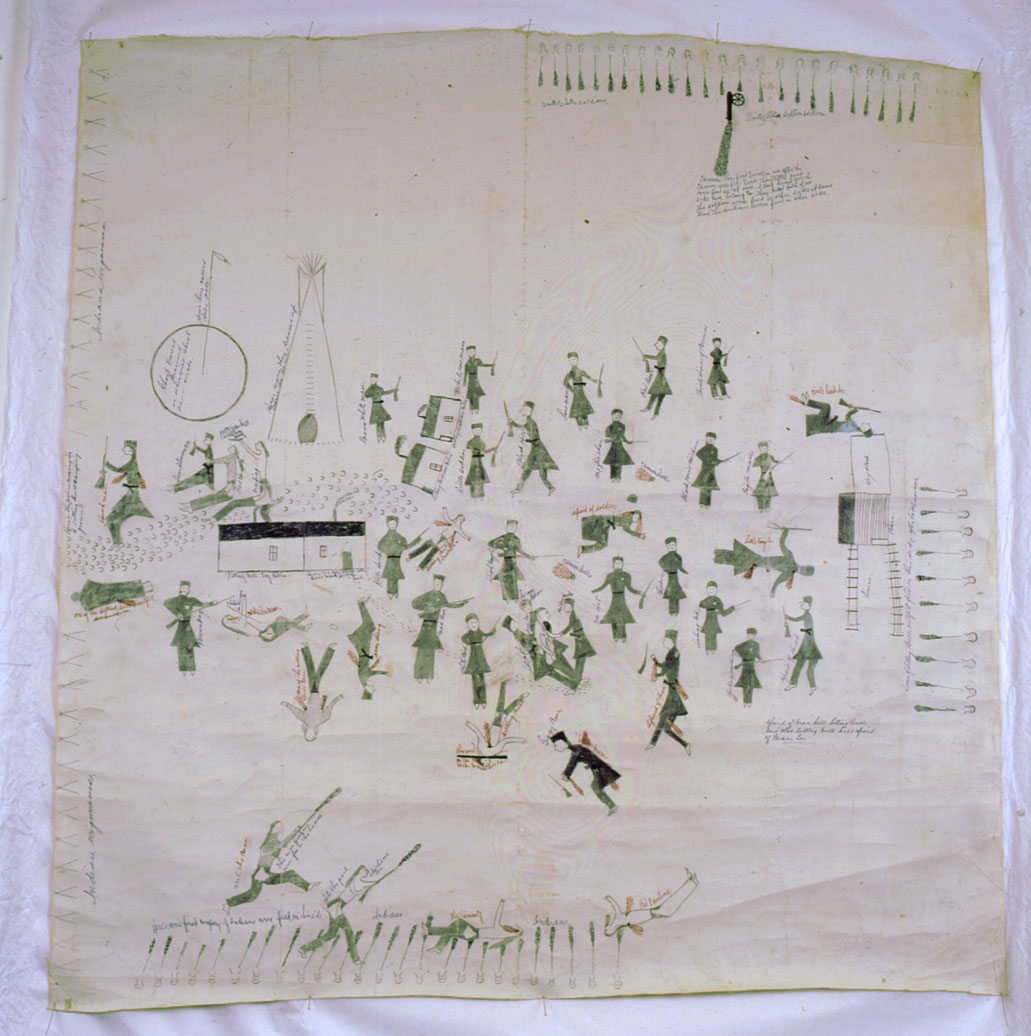

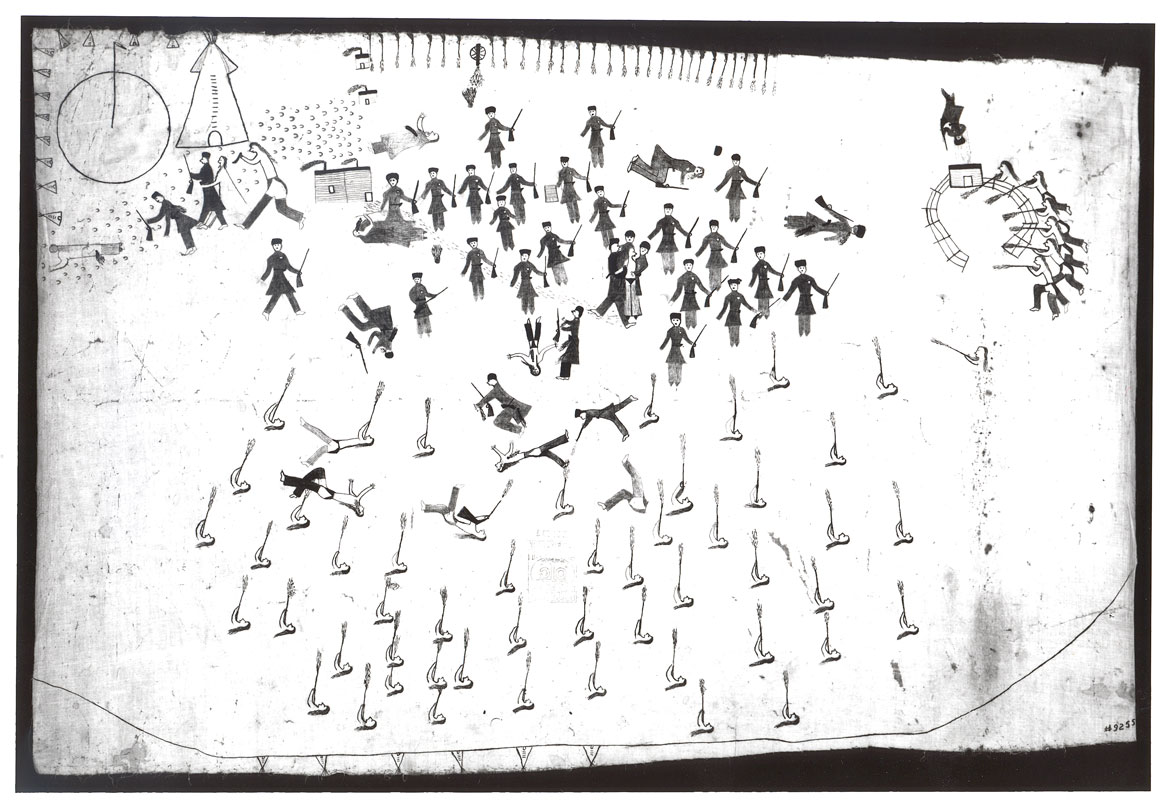

The State Historical Society of North Dakota has four pictographs of the death of Sitting Bull in its museums and archives collections. The pictographs document the events of December 15, 1890 at Sitting Bull’s cabin. Each of the pictographs is slightly different from the others. It is important to remember that eye-witnesses see the event from different positions and may have somewhat different memories of the event. Each of these pictographs was drawn at least 20 years after the event.

Only one of the pictographs has a written interpretation. The others have some writing on the cloth which identifies individuals. Each artist uses slightly different ways of showing what happened. Red lines emerging from the body of an individual usually indicate wounds. Bodies lying on the ground represent dead or severely wounded individuals. Men with dark shirts and light blue pants are Indian police officers. Lines indicate the direction of a gunshot or the direction that people moved. Hoof prints indicate the movement of horses.

Pictograph Number 962 was drawn on a piece of muslin cloth that measures 36 inches by 54 inches. We do not know who drew this pictograph. The picture appears to be simpler, perhaps less complete than the other pictographs. Some of the Indian policemen held the horses while others arrested Sitting Bull. We can see the wounds on individuals. We can see Sitting Bull’s cabin and barn with smoke rising from the chimneys. Even without detail, we can see that the event was violent and many people were wounded.

Pictograph Number 941 was also painted on muslin. The cloth measures 70 inches by 72 inches. It was made around 1915 at Standing Rock agency. Most of the people in the pictograph are identified by name. In this list, one asterisk (*) means that person was wounded. A name with two asterisks (**) indicates that person was wounded and died. The Indian policemen included Afraid of Hawk, Alex Middle*, Arm**, Brown Wolf, Bull Head*, Hawk Man*, High Eagle, Little Eagle**, Looking Elk, Cross Bear, One Feather, Red Tomahawk, Shave Head*, Stone Man, Waketemani, Warriors Fear Him**. The other Lakotas drawn in this pictograph include Black Bird**, Black Thunder, Brave Thunder**, Bull Ghost*, Crow Foot**, Grasping Bear**, Iron White Man, Jumping Bull**, Red Crow, Red Hair*, Sitting Bull**, Spotted Horn**, Strikes the Kettle*.

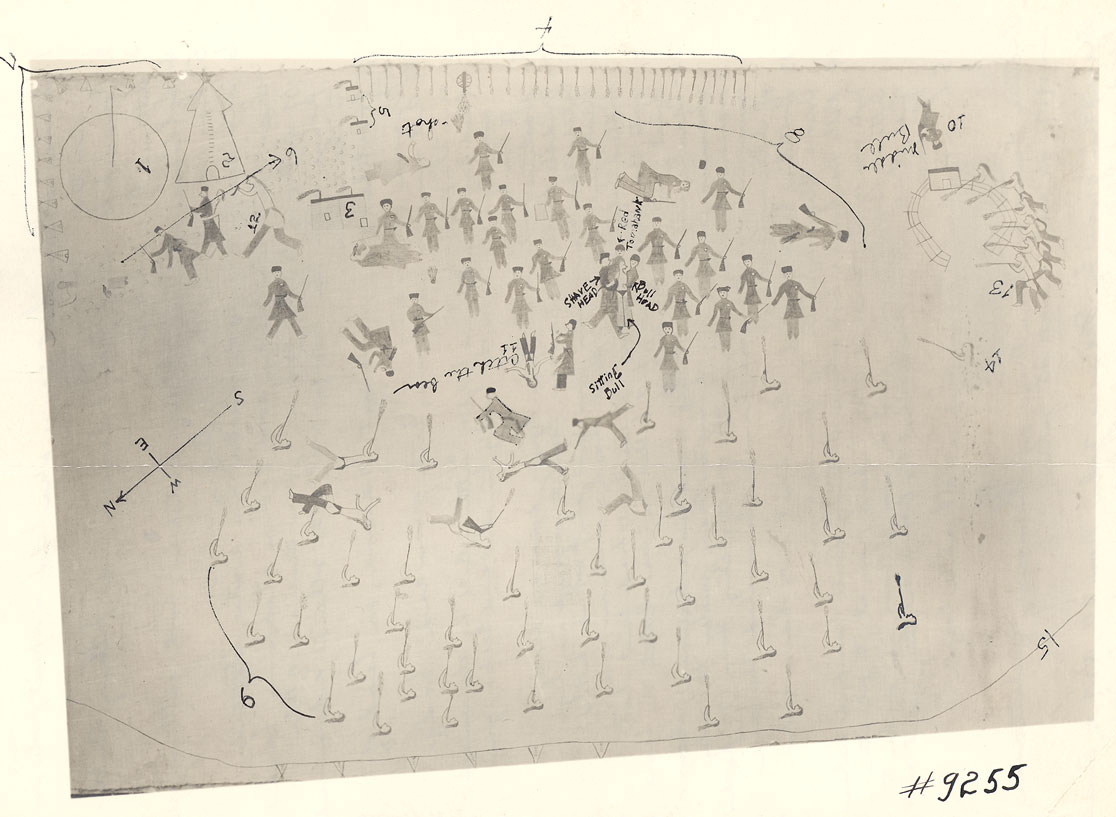

Pictograph Numbers 9254 were both drawn by Stone Man, a Yanktonai Indian policeman. Number 9254 is about 36 inches by 32 inches. It was drawn on muslin. In 1917, Stone Man made the pictograph Number 9255. Like the other pictographs it was drawn on muslin. Stone Man made a second version of the pictograph around 1925.

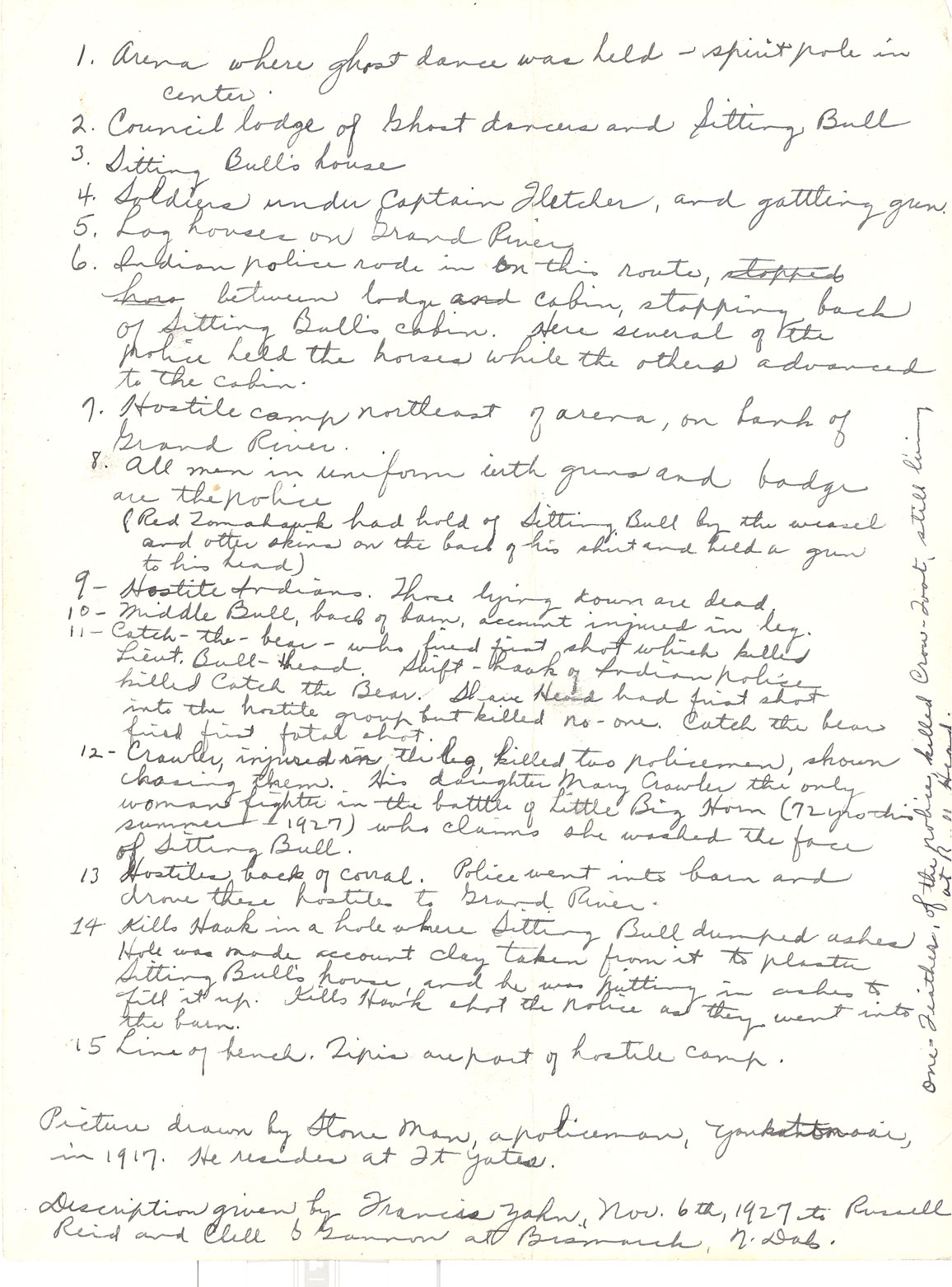

Stone Man described the events in his pictographs to Frank Zahn.Frank Zahn was the son of a U. S. Army soldier who fought with Major Reno’s troops at the Battle of the Little Big Horn. His mother was a Lakota woman. Frank was born a few months before Sitting Bull was killed on the Standing Rock Reservation. He grew up on the reservation living close to his mother’s relatives and learning the life of the Lakotas. He was educated at boarding schools, and attended Carlisle Indian School where he studied law. He enlisted as a soldier during World War I (1917–1918.) He worked as an interpreter for many years, and then became a judge of the Court of Indian Offenses. Judge Frank Zahn married Gladys, a teacher at Fort Yates, and together they raised five children. Judge Zahn continued to serve the court until his retirement. When Judge Zahn gave the pictograph to the State Historical Society of North Dakota museum in 1927, he identified events at specific places in the pictograph. Museum director Russell Reid numbered the events on a copy of the pictograph and wrote down Judge Zahn’s words. Judge Zahn used the term “hostiles” which was, at that time, a commonly used term to identify Lakotas who did not readily cooperate with reservation agents.

Below is a transcription of the words Frank Zahn said that Stone Man used to describe the pictograph number 2. You can look at both the numbered image of the pictograph and the unnumbered image of the pictograph as you read the description.

1. Arena where ghost dance was held- spirit pole in center

2. Council lodge of Ghost dancers and Sitting Bull.

3. Sitting Bull’s house

4. Soldiers under Captain Fletcher [Fechet], and gattling [rapid-fire] gun.

5. Log houses on Grand River [on the South Dakota side of the Standing Rock Reservation where the event took place].

6. Indian police rode in on this route, between lodge and cabin, stopping back of Sitting Bull’s cabin. Here several of the police held the horses while the others advanced to the cabin.

7. Hostile camp northeast of arena, on bank of Grand River.

8. All men in uniform with guns and badge are the police (Red Tomahawk had hold of Sitting Bull by the weasel and otter skins on the back of his shirt and held a gun to his head.)

9. Hostile Indians. Those lying down are dead.

10. Middle Bull, back of barn, [by this] account, [he was] injured in leg.

11. Catch-the-bear who fired first shot which killed Lieut. Bull-Head. Swift-hawk of Indian police killed Catch-the-bear. Shave Head had first shot into the hostile group but killed no-one. Catch the bear fired first fatal shot.

12. Crawler, injured in the leg, killed two policemen, shown chasing them. His daughter Mary Crawler the only woman fighter in the battle of the Little Big Horn (72 [years old] this summer – 1927) who claims she washed the face of Sitting Bull.

13. Hostiles back of corral. Police went into barn and drove these hostiles to Grand River.

14. Kills Hawk in a hole where Sitting Bull dumped ashes. Hole was made [by this] account [as] clay taken from it to plaster Sitting Bull’s house, and he was putting in ashes to fill it up. Kills Hawk shot the police and they went into the barn.

15. Line of bench [of river bank.] Tipis are part of hostile camp.