When the Cheyennes and the families of Crazy Horse’s Oglalas reached Sitting Bull’s camp, the village numbered a total of 235 lodges (tipis, or households.) There were, on average, about two fighting men per lodge. In addition, Sitting Bull expected some of the reservation Lakotas to come north to the Yellowstone to hunt in the summer. A larger group provided more strength against an attack, but a large village had to move every two to five days to find game for food and grass for the ponies. By early June, the combined villages numbered 461 lodges. Military reports indicated that there were many more warriors in the villages than the lodge count suggests.

As more families and warriors joined the village, the leaders met in council and decided to prepare for war. They expected the soldiers to attack again. Sitting Bull was the leader of the combined villages and had the support of Crazy Horse and the Cheyennes. Wooden Leg, a Cheyenne, said that Sitting Bull had a “kind heart and good judgment as to the best course of conduct. . . . He was . . . brave, but peaceable.”

Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse and the other chiefs agreed that they would not seek out the Army for a battle. However, they would be prepared for battle at any time. The young men, however, saw things differently and found several opportunities to steal horses from soldiers or the Army's Crow Indian scouts. The young warriors brought information about the Army back to the main village.

On June 17, the older leaders accepted the arguments of the younger men of the tribes. The young men led the Lakotas and Cheyennes out to meet General George Crook’s troops on Rosebud Creek. Crook’s troops were caught by surprise. At Rosebud Creek, the Lakotas faced 1,000 soldiers with superior weapons. As the sun went down, both the soldiers and the Lakotas gave up the battle. Twenty Lakotas and one Cheyenne diedWhile reports of the number of soldiers killed and wounded is usually quite accurate, it is far more difficult to determine how many Indians might have died in battle. If at all possible, Lakotas removed their dead from the field of battle. The Army tried to estimate the number of dead among the Lakotas, but often inflated the numbers. fighting. Nine soldiers were killed in the battle. Many more, on both sides, were wounded.

General Crook claimed that he had defeated the Lakotas on Rosebud Creek, but historians argue that the Lakotas won the battle. They faced a larger fighting force that was well-armed. At the end of the day, the Army was forced to retreat to its base camp for food and medical care. (See Document 2)

The Lakotas and Cheyennes established a new village site on the river they called the Greasy Grass which the Army called the Little Big Horn River. In the village, they mourned their dead and celebrated a great victory over the Army. They still expected another attack, but by now, agency Indians had joined the village. More than 1,000 lodges and nearly 2,000 warriorsThe first reports from the Army stated that between 2,500 and 3,000 warriors fought in the battle of the Little Big Horn. While the soldiers faced a far larger fighting force than they had expected, modern scholars put the number of warriors at closer to 2,000 than 3,000. gathered on the Greasy Grass.

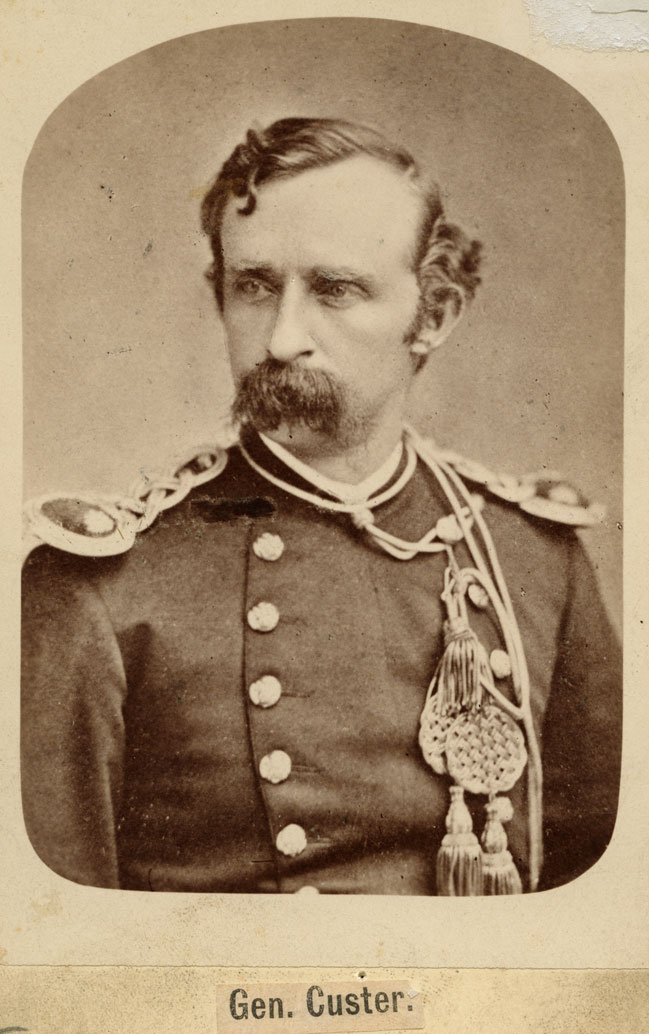

On the morning of Sunday, June 25th, Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong CusterCuster’s official rank was Lieutenant Colonel. He was in command of Fort Abraham Lincoln and the 7th Cavalry (mounted soldiers) stationed there. During the campaign against the Sioux in June 1876, he reported to General Alfred Terry. Custer is sometimes called General Custer because of his brevet promotion during the Civil War. Brevet refers to a battlefield promotion. After the war, all brevet ranks were converted to lower ranks and Custer became a Lieutenant Colonel. Custer was famous for his daring in battle during the Civil War. Because he was so young during the Civil War, he was called “the boy General.” Custer, known as Autie to his friends, was 36 years old when he died at the Battle of the Little Big Horn. (See Image 7) learned the location of the Sioux village from his Arikara scouts.The Arikara scouts were enlisted in the Army. They had served as scouts at Fort Rice and Fort Abraham Lincoln and had ridden with Custer’s troops to the Black Hills in 1874. Some of the scouts stayed to engage in the battle, though they were not trained to fight as the soldiers did. Some Arikaras, including Bob-tail Bull and Bloody Knife, lost their lives while fighting with Custer’s men. Other scouts tried to drive away the Lakotas’ ponies. Many years later, the surviving Arikara Scouts told their story to an interviewer. The interviews were published in <em>Collections of the State Historical Society of North Dakota,</em> Vol. 6 (1920.) (See Image 8) In preparation, Custer divided his command into three fighting groups and a supply train. Major Reno with 125 soldiers and Captain Benteen with 140 soldiers went in different directions. The 210 soldiers with Custer charged into the village. (See Map 3.)

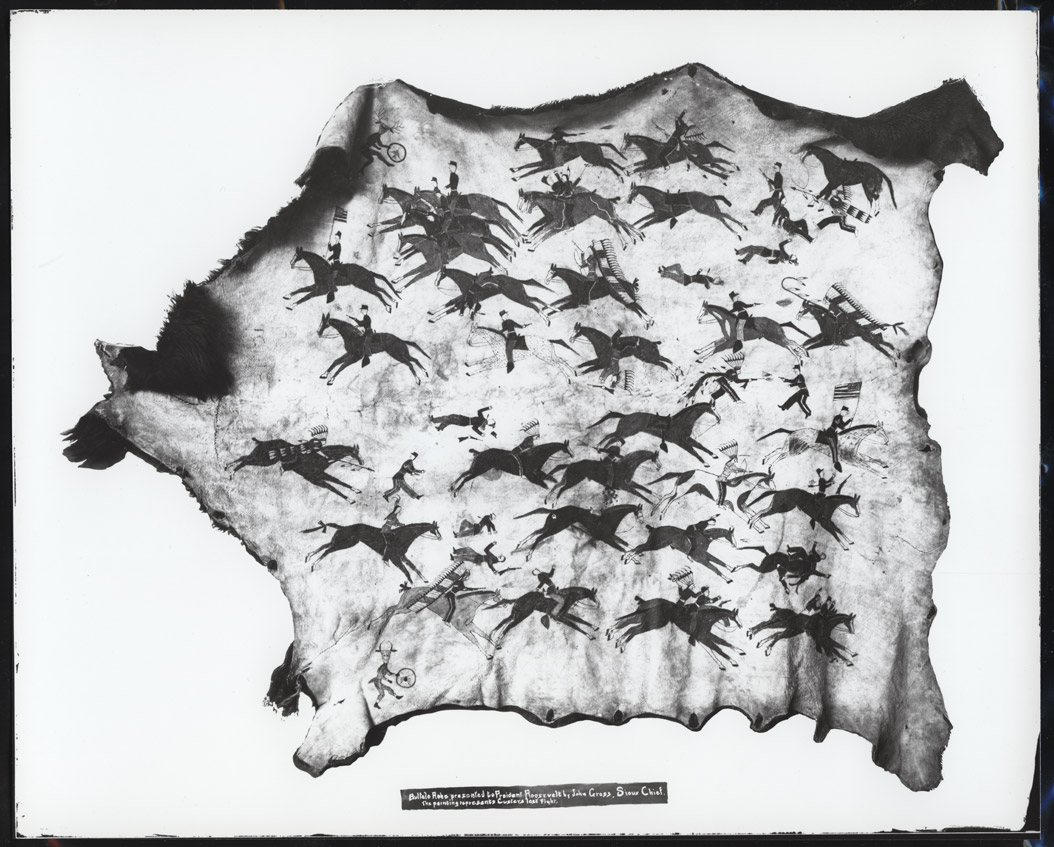

Reno’s command had to retreat twice and suffered heavy casualties. Major Reno and his soldiers remained under siege on a ridge until General Terry arrived with reinforcements on Monday June 26th. No one was able to communicate with Custer’s men. Sometime during the battle on June 25th, Custer and all of his soldiers were killed. There were no survivors to explain exactly what happened. (See Image 9.)

On the 26th, the Sioux village packed up and began to move away. The Lakotas had won the battle, but they knew that more soldiers would come and they would have to move their families to safety.

Why is this important? The Battle of the Little Big Horn is often called the last battle of the Plains Indian wars. For that reason alone it was significant. Many large and small battles had taken place throughout the Great Plains since the 1850s. The people of the United States were ready to put an end to the conflict.

From the perspective of the Lakotas, the battle had a different meaning. They had not sought the battle, but under the brilliant leadership of Sitting Bull they were prepared. At Rosebud Creek and on the Greasy Grass, the Lakotas defended their families and their way of life. In their victory, they created a lasting memory of the power of the Lakota people that lasted through generations.

However, the battle also led the Army to send greater military strength against the non-reservation Indians. In addition, the buffalo that supported the Lakota way of life were beginning to disappear from the northern Great Plains. It was just a matter of a few years before the Lakotas would be forced to move to a reservation.

Source: Robert M. Utley, The Lance and the Shield: The Life and Times of Sitting Bull (New York: Ballantine Books, 1993.) Quotation from Wooden Leg, pg 133.

Document 2

The Army prepared to follow its plan to attack the Sioux in a major, decisive battle. The plan to attack during winter did not work. Soldiers and their horses could not stand the cold and deep snow of a northern Plains winter. However, by spring the Army was ready.

The excerpts below tell of the Army’s preparation for battle. The letters were carried from the field to forts by soldiers or Indian scouts. Then, the letters were telegraphed to other forts or to headquarters. Communication was slow and cumbersome. The Army struggled to get accurate information and often passed on rumors instead of facts.

These excerpts describe the Battle of the Little Big Horn which took place on June 25 between the Cheyenne and Lakota warriors led by Sitting Bull and the 7th Cavalry led by George Armstrong Custer. The final document is the recorded memoir of Mrs. Spotted Horn Bull who was at the Battle of the Little Big Horn.

In the excerpts, ellipses (. . . ) indicate where words have been removed to shorten the entry. Editor’s additions to the text are enclosed within brackets ([XXX] .) Copies of the full text of the letters are attached. You can read more of these officers’ letters at: House Documents, Otherwise Publ. as Executive Documents: 13th Congress, 2d Session-49th Congress, 1st Session (Google e-Book)

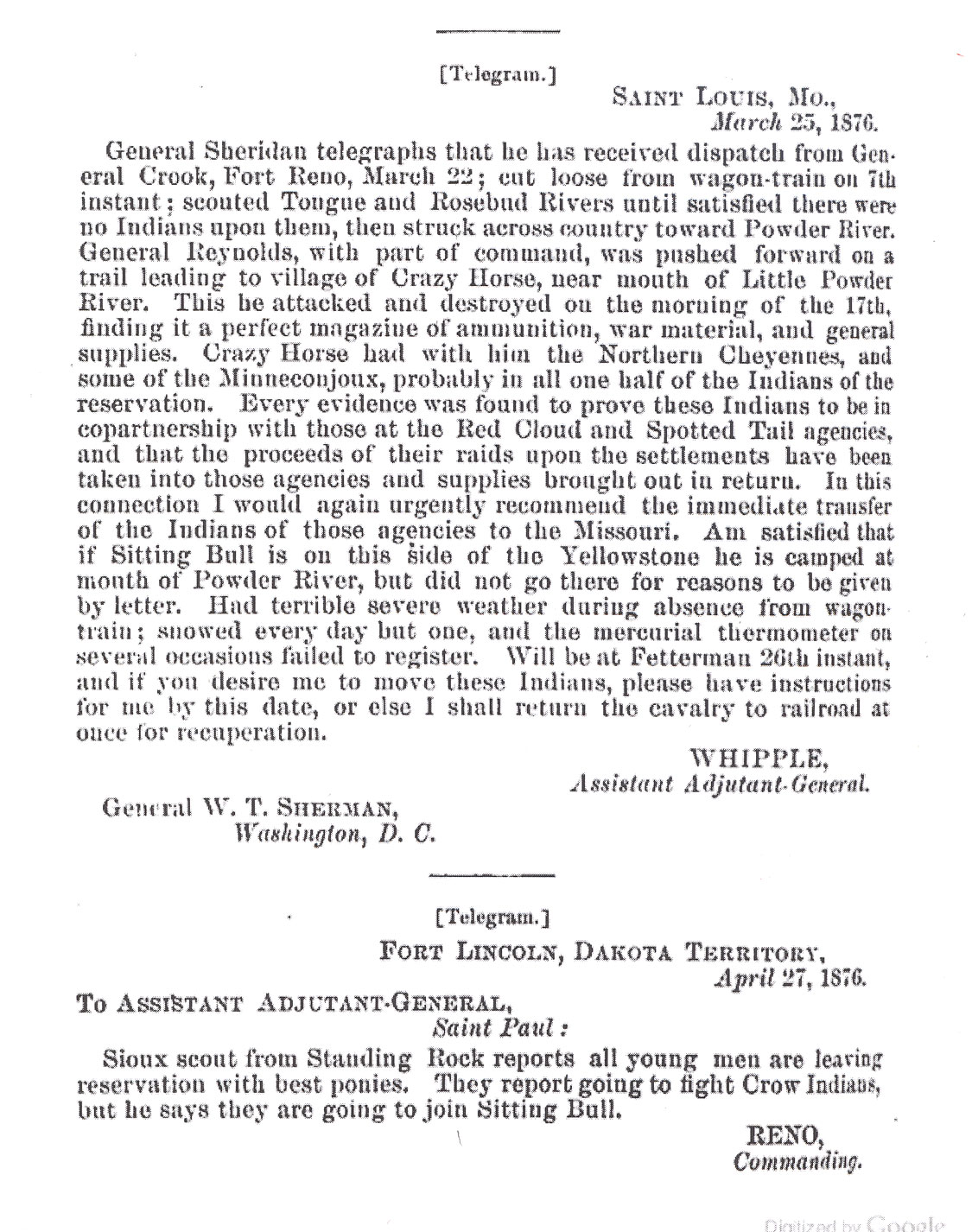

April 27, 1876. Major Reno to Assistant Adjutant–General, St. Paul.

“Sioux scout from Standing Rock reports all young men are leaving reservation with best ponies. They report going to fight Crow Indians, but he says they are going to join Siting Bull.”

May 29, 1876. General Phillip Sheridan to General W. T. Sherman.

“Brigadier-General Terry moved out his command from Fort A. Lincoln in the direction of the mouth of the Powder River. . . .

Brigadier-General Crook will move from Fort Fetterman with a column about the same size. Col. John Gibbon is now moving down north of the Yellowstone and east of the mouth of the Big Horn. . . .

I presume that the following will occur:

General Terry will drive the Indians toward the Big Horn Valley, and General Crook will drive them back toward Terry; Colonel Gibbon [will] . . . intercept . . . such as may want to go north of the Missouri to the Milk River.

The result of the movement of these three columns may force many of the hostile Indians back to the agencies on the Missouri River and to the Red Cloud and Spotted Tail agencies on the northern line of Nebraska, where nearly every Indian, man, woman, and child, is at heart a friend.

It is easy to foresee the result of this condition, that as soon as the troops return in the fall, the Indians will go out again, and another campaign, with all its expenses, will be required. . . . Two posts [should] be established on the Yellowstone, and . . . the military [should] be allowed to exercise control over the Indians at the agencies, . . .

I hope that good results may be obtained by the troops in the field. . . . We might as well settle the Sioux matter now. It will be better for all concerned.”

May 30, 1876. General Phillip Sheridan to General W. T. Sherman.

“. . . the information from Crook goes to show that all the agency Indians capable of taking the field are now, or will be, on the war-path.”

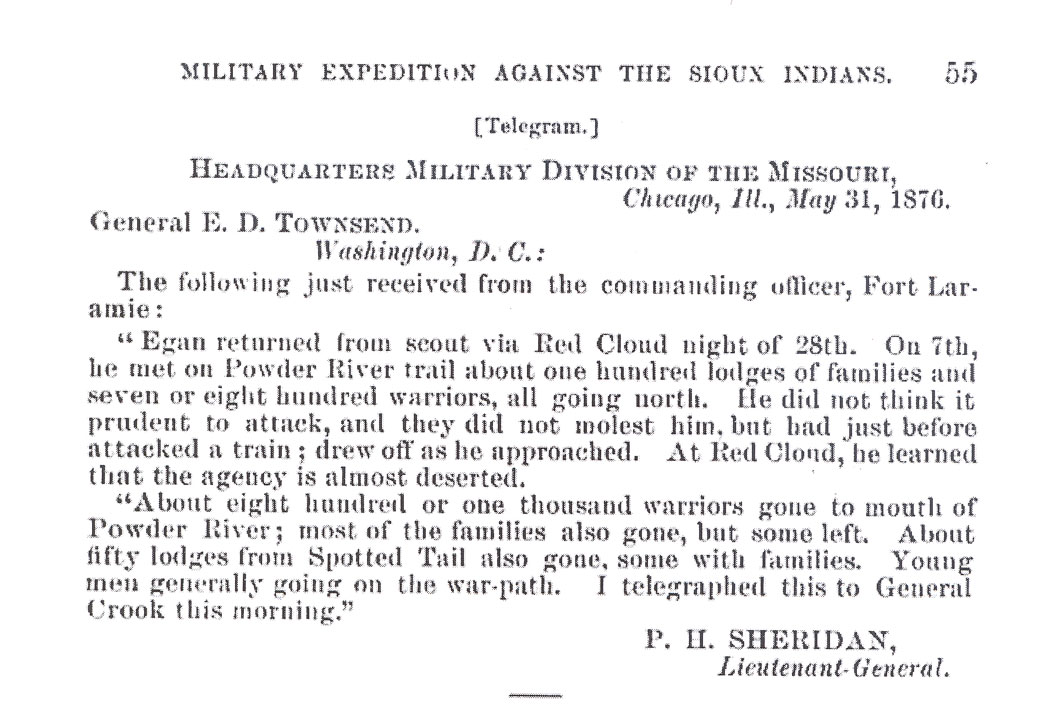

May 31, 1876. General Phillip Sheridan to General E. D. Townsend.

“ ‘Egan returned from scout via Red Cloud night of 28th. On 7th, he met on Powder River trail about one hundred lodges of families and seven or eight hundred warriors, all going north. He did not think it prudent to attack, and they did not molest him, but had just before attacked a train; drew off as he approached. At Red Cloud [agency], he learned that the agency is almost deserted.

About eight hundred or one thousand warriors gone to mouth of Powder River; most of the families also gone, but some left. About fifty lodges from Spotted Tail also gone, some with families. Young men generally going on the war-path.’ ”

June 4, 1876. J. S. Poland, Sixth Infantry Standing Rock to Assistant Adjutant-General, Department of Dakota, St. Paul, Minnesota.

“. . . a large war party, composing Indians from Spotted Tail’s and Cheyenne River Indian agencies, left the latter place with the avowed intention of going to Fort Berthold agency to attack the [Arikaras.] I learn from reliable authority to-day that Kill Eagle, a prominent chief of the Blackfeet Sioux . . . lately left with 20 lodges, . . . [to join] the hostile Sitting Bull. Many of the young men belonging to this agency have left the agency. . . . The principle chiefs remain here, and did they receive an adequate and proper supply of food would . . . continue here, disposed upon every consideration to preserve the peace. [Poland accuses agent Burke of not distributing food supplies properly.]

“In consideration of the organized expeditions against the hostiles, their relatives, should these agency Indians generally join the hostile camp it ought to be charitably attributed to the want of food two years in succession, which they have been compelled to suffer, and which if issued to them, would keep them, as no other bond or attraction can, at these reservation-homes, with confidence in the promises of their great father.”

June 8, 1876. R. Williams, Assistant Adjutant-General to Assistant Adjutant-General, Headquarter, Military Division of the Missouri, Chicago, Illinois.

“. . . [a man named] Hand, Indian courier from Red Cloud, brings report that just before he left an Indian arrived from the mouth of Tongue River; found there twelve hundred and seventy-three lodges under Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse, and others, on their way to Powder River to fight General Crook. . . .”

June 19, 1876. General George Crook to General Phillip Sheridan. Camp on South of Tongue River, Wyoming.

“When about forty miles from here, on Rosebud Creek, Montana, morning of 17th . . . scouts reported Indians in vicinity, and within a few minutes we were attacked in force, the fight lasting several hours. . . . [The Sioux] displayed strong force at all points, occupying so many and such covered places that it is impossible to correctly estimate their numbers. The attack, however, showed that they anticipated that they were strong enough to thoroughly defeat the command. . . . The command finally drove the Indians back in great confusion, following them several miles. . . .”

June 27, 1876. General Alfred H. Terry to Adjutant-General of Military, Division of the Missouri. First report on the Battle of the Little Big Horn.

“It is my painful duty to report that day before yesterday, the 25th [June], a great disaster overtook General Custer and the troops under his command. . . . Of the movements of General Custer and the five companies under his immediate command, scarcely anything is known from those who witnessed them, for no officer or soldier who accompanied him has yet been found alive. . . . The scout discovered three Indians, who were at first supposed to be Sioux, but when overtaken they proved to be Crows who had been with General Custer. They brought the first intelligence of the battle. Their story was not credited. It was supposed that some fighting, perhaps severe fighting, had taken place, but it was not believed that disaster could have overtaken so large a force as twelve companies of cavalry. . . .”

1909. Mrs. Spotted Horn Bull’s memories of the Battle of the Little Big Horn (from McLaughlin, My Friend the Indian)

“That night the Sioux, men, women, and children, lighted many fires and danced ; their hearts were glad, for the Great Spirit had given them a great victory. . . . “There was fighting the next day, but the Sioux knew early in the day that many soldiers were coming up from the north, and preparations were made to leave for new hunting-grounds. And while our hearts were singing for the victory our braves had won, there were wailing women in the village, for they had their dead. . . .

“So we went out from Greasy Grass River, and left Long Hair and his dead to their friends. The people scattered and the pursuit did not harm us. But I still remember the bitterness of the suffering of the Sioux that winter, after we had met and talked with Bear Coat [General Miles] on the Yellowstone, when we were on our way north into the land of the Red Coats, where we remained five winters, and were frequently very destitute, while we remained there.”