After the Battle at the Greasy Grass River, Sitting Bull and the other leaders faced many decisions. They decided to split up into smaller bands that could move faster and hunt more effectively. Most of the Lakotas and Cheyennes remained in eastern Montana to hunt for the rest of the summer.

The Army buried the dead at the battlefield and tended to the wounded. More soldiers arrived at the forts. In August, the Army started a new campaign to locate the Sioux and bring them to the reservations.

General Crook’s first effort resulted in failure. The weather was too rainy for swift travel. Crook failed to provide enough food for his troops and livestock. During his campaign from the Little Missouri River to the Black Hills, Crook stumbled upon the camps of the Lakotas who were hunting in the Slim Buttes northeast of the Black Hills. Among the leaders of these groups were Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse. The Army attacked the unprepared village during the night. Some women and children were killed. Before the Army gave up the fight, the soldiers destroyed the lodges and household goods.

Before General Crook’s troops attacked the village, some of the bands were discussing the possibility of surrendering and taking up life on a reservation. However, the deaths of their women and children and the destruction of their village changed their minds.

During the Fall of 1876, Congress presented an ultimatum to the Sioux nation. The Lakotas had to give up all claims to the Black Hills or they would no longer receive rations. Chiefs who lived at the agencies agreed to the forced cession of their lands so that they could continue to feed their people.

About the same time, General Phillip Sheridan, who commanded all the Army divisions in the West, planned a major campaign against the Sioux. He placed the Army in charge of reservation agencies and planned to disarm Sioux to prevent them from leaving the reservation to hunt. Following Sheridan's actions, the civilian Commissioner of Indian Affairs no longer controlled the agencies.

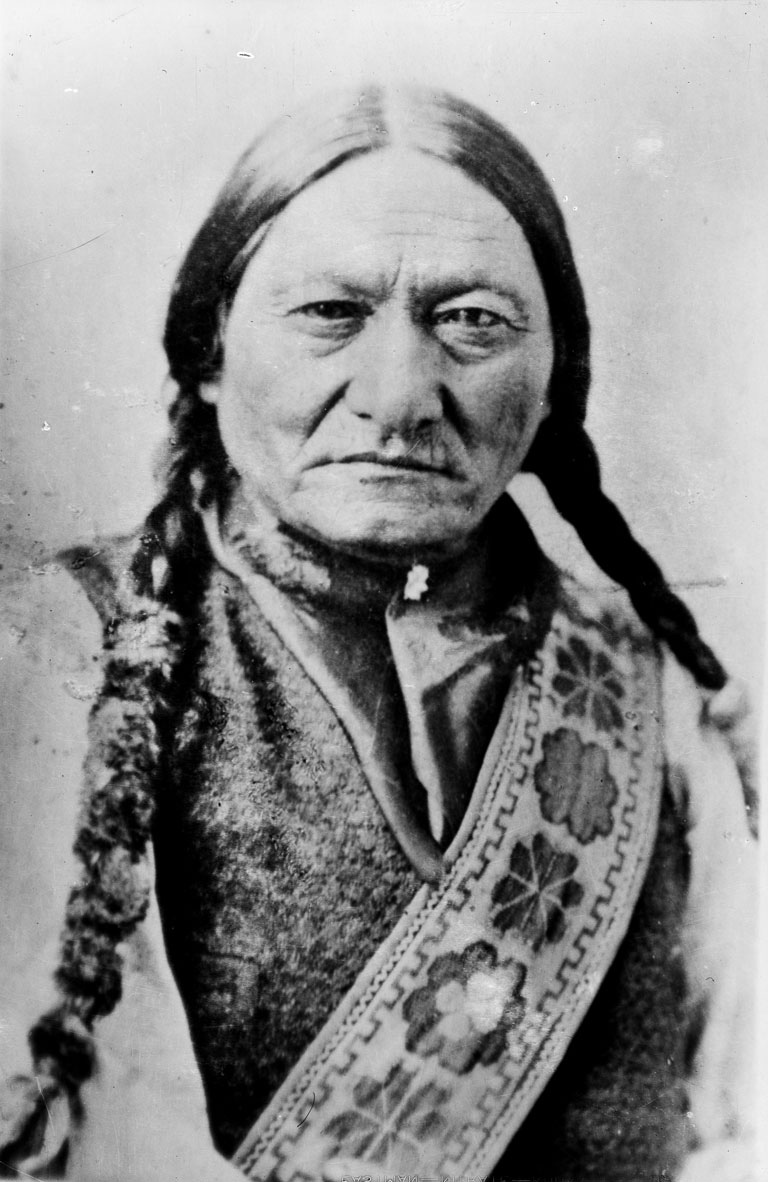

While Crook was disarming the hunters at Standing Rock, Sitting Bull led the Hunkpapas north toward the buffalo country along the Yellowstone River. (See Image 10) The Hunkpapas, along with their friends among the Minneconjou and Sans Arc Lakota bands, entered into conversations with Army officers a couple of times during October. Eventually, the Minneconjous and the Sans Arcs decided to surrender and report to the Cheyenne River agency. Sitting Bull became more determined to continue his defense of his way of life and of the hunting lands of eastern Montana. The officers made it clear that they would not allow Sitting Bull to hunt or live in the land of the Yellowstone or Missouri Rivers. Throughout the cold winter of 1876-1877, the Army harassed the Lakotas to prevent them from finding food and shelter.

Sitting Bull still believed that the Lakotas could win a war with the U. S. Army, but he listened to those who suggested that it was time to surrender. Sitting Bull was concerned that if he surrendered, the soldiers would take his guns and horses and he would never hunt again. During the first week in May, Crazy Horse surrendered in Nebraska and Sitting Bull crossed the “holy trail” into Canada. Over the next four years, in Canada, the Hunkpapas rested and hunted. However, in Canada, bison were beginning to disappear. The Canadian soldiers did not attack the Lakotas, but they had promised the United States that the Lakotas would stay in Canada.

As the Lakota people became hungry, small groups left Canada to return to the United States and settle on a reservation. They longed for their friends and families who stayed on the reservations. However, when Gall and Crow King led their families to Fort Buford in 1880, they were attacked by soldiers. Eight people died. Sitting Bull knew that there was still danger in the United States for Lakotas.

Finally, in July, 1881, Sitting Bull and 200 Lakotas reported to Fort Buford at the confluence of the Yellowstone and Missouri Rivers. They gave up their guns and their horses. Sitting Bull and some of his family were taken to Fort Randall, more than 300 miles south of Standing Rock agency. They were held there as prisoners of war until 1883 when they returned to their families at Standing Rock.

Why is this important? Sitting Bull did not lead an army; he led families. The relentless pursuit by the U. S. Army after the Battle of the Little Big Horn wore down the Lakotas. Though Sitting Bull wanted to live in peace and continue the way of life he had known until 1876, the Army made that impossible. Sitting Bull had to consider the welfare of the children. (See Image 11) In order for the children to thrive and grow to adulthood, Sitting Bull led the Hunkpapas across the border into Canada. When the Canadian prairies could no longer support the families, the Hunkpapas had to cross back into the United States so that the children would not starve.

This story has many meanings. It is about how the Lakotas tried to find living space where they could raise their children. The story tells us how the Lakotas tried to maintain the strength and power of their culture. The Lakotas were finally forced onto a reservation, but Sitting Bull’s dignity, wisdom, and concern for his people never dimmed.