Sitting Bull, or Tatanka Iyotanke, was born sometime between 1831 and 1837 at a place the Dakotas called Many Caches. Today, that location is near Grand River in South Dakota. Sitting Bull’s father, also known as Sitting Bull, was a warrior of great courage. His family was part of the Hunkpapa (also called Uncpapa) band of the Western or Teton Dakotas (also called Sioux or Lakotas).

Sitting Bull's boyhood name was Jumping Badger, but his friends called him “Slow” because of his deliberate way of doing things. While still a young man, Sitting Bull demonstrated his intelligence, courage, and leadership. One of his biographers called him a “natural strategist of no mean courage and ability.” This courage served him well, especially after 1862 when soldiers and gold-seekers repeatedly entered the land guaranteed to the Sioux by treaty. The emigrant and Army wagon trains disturbed the bison herds and destroyed the grass. Soldiers came to protect the pioneers, but Sitting Bull believed that his band had no quarrel with the United States.

After battles with the Army in 1863 (Whitestone Hill), 1864 (Killdeer Mountain), and 1865 (at Fort Rice), Sitting Bull was recognized by the Army for his leadership in battle. By 1868, he was considered to be one of the most important leaders of the Teton Dakotas (also called Lakotas). Even though Sitting Bull was respected, he could not tell people what to do. Decisions were usually made by a group of men after discussing problems at length.

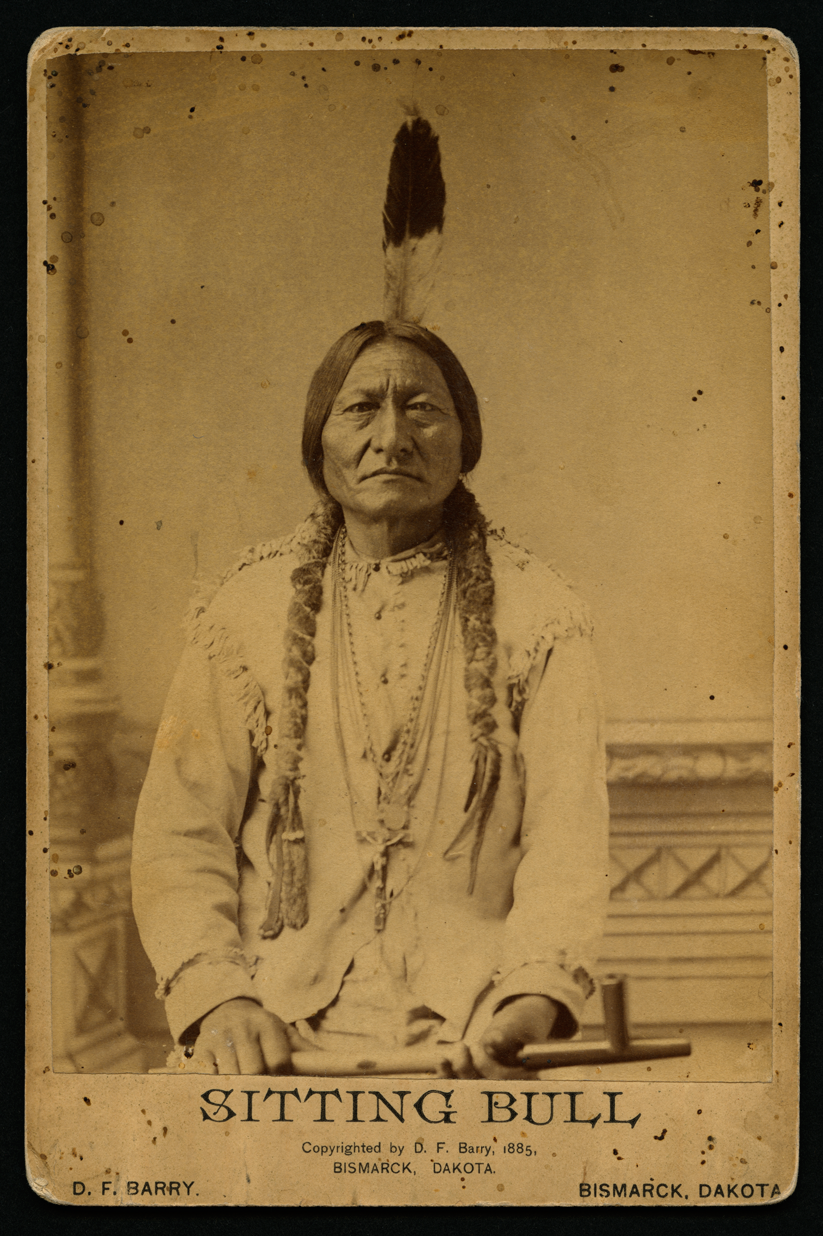

The Army saw Sitting Bull as a fierce and powerful opponent. As the Northern Pacific Railroad prepared to build through Dakota treaty lands, Sitting Bull demonstrated his fearlessness by sitting with four other warriors on the prairie in front of the soldiers protecting the railroad workers. They smoked their pipes as the soldiers fired their guns at them. When they finished smoking, they got up and walked away. (See Image 1.)

In 1868, the new Treaty of Fort Laramie granted to the Western Dakotas “absolute and undisturbed use and occupation” of an area in southwestern Dakota Territory that included the Black Hills. These forested hills were important to the Dakotas as sacred and spiritual ground. This was their homeland. However, in 1874, Colonel George Custer led an expedition to the Black Hills to map the area and to see if rumors of gold were true. Soldiers brought back information that there was much gold in the Black Hills. The result was a rush to the gold mines of the Black Hills.

The federal government tried to resolve the conflict with the Dakotas by offering to buy the Black Hills from the tribes, but the tribes refused to sell. The government then demanded that the Dakotas go to reservations set aside for them. Those Dakotas who refused this order were considered hostile and subject to military action. Sitting Bull and his people, along with many other tribes, refused to accept this violation of the 1851 and 1868 treaties. Sitting Bull began a campaign of harassment against the railroad, the Army, and the few settlers who entered Sioux country. The conflict led to the battle at the Little Big Horn River in Montana in 1876.

Sitting Bull was one of the leaders in the battle on the river the Lakotas called the Greasy Grass. Thousands of Lakota warriors with their Cheyenne allies defeated the Army. None of Colonel Custer’s 7th Cavalry troops survived the battle.

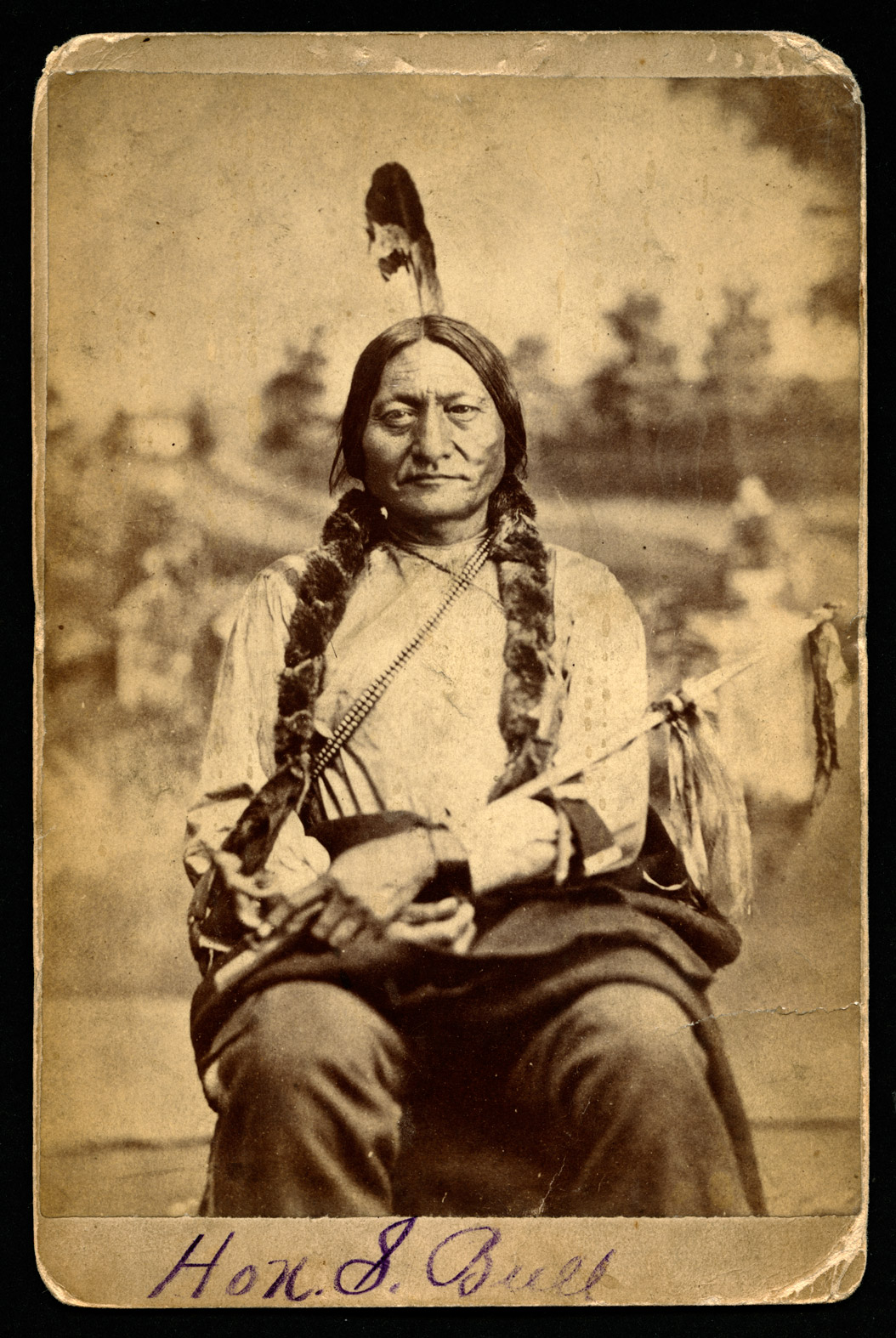

Although the Hunkpapas and their allies won the battle, Sitting Bull knew that more soldiers would come after them. With his people, Sitting Bull crossed the border into Canada in May 1877. They stayed there until July 1881. By then, there were too few bison to support the Hunkpapas. Starving, the Hunkpapas surrendered at Fort Buford (Dakota Territory) in 1881 and reluctantly accepted a new life at Standing Rock Reservation. (See Image 2.)

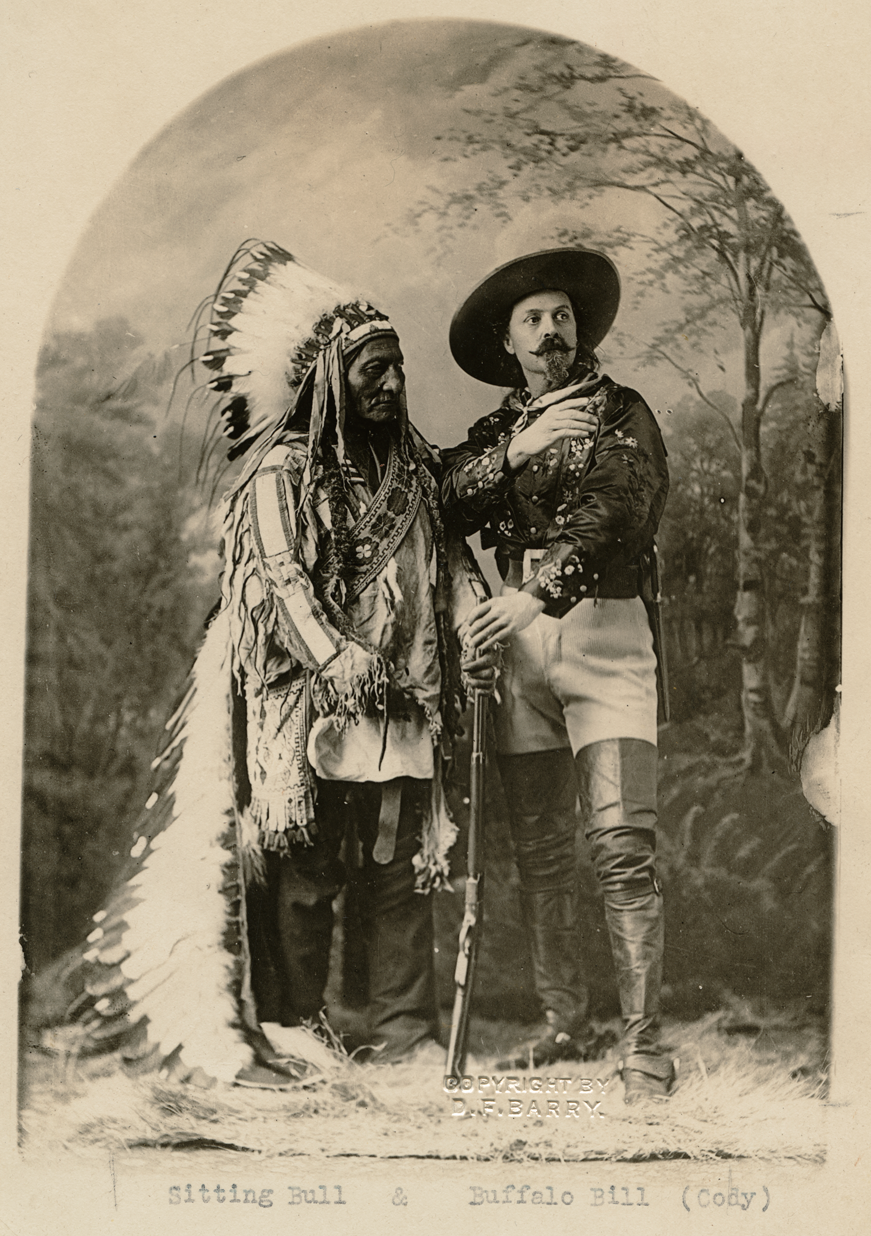

Sitting Bull was sent to a military prison at Fort RandallWhile he was under guard at Fort Randall, Sitting Bull drew pictures of his life story. Like many other Indians, he no longer had access to the traditional bison hide for his autobiographical pictures so he drew them with colored pencil in a ledger book (a lined book used by clerks to keep accounts.) Most of his pictures show him committing brave deeds in battle. Sitting Bull learned to sign his name in English and signed each of the pictographs. In addition to his drawings, the ledger book contained newspaper clippings about Sitting Bull. The ledger book which contains the pictograph, or autobiography, of Sitting Bull is held by the Smithsonian Institution.for two years. When he returned, the reservation agent treated Sitting Bull as though he had never been a leader. He was sent to work in the farm fields. (See Image 3.) He followed these orders with dignity. In 1885, Sitting Bull briefly joined Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West Show. He spent four months traveling with Cody’s show, earning $50 per week and earning a little more signing autographs. (See Image 4.)

In December 1890, when the Ghost Dance reached Standing Rock reservation, the agent still feared Sitting Bull’s power as a leader and had him arrested. Sitting Bull’s followers came to his aid and the confusion led to a gunfight. Sitting Bull was killed in the fight.

Sitting Bull’s death did not put an end to his reputation as a man of courage who did as much as possible to protect his people. For years, people talked of his actions and repeated his words. He understood, even after surrendering, that “No white man controls our footsteps. If we must die, we die defending our rights."

Why is this important? Sitting Bull was one of many leaders of the Teton Dakotas. Some Dakotas recognized that the United States and the Army would never leave them to live the way they had for hundreds of years. These leaders signed the treaties and brought their families to reservations.

Sitting Bull resisted both military and diplomatic pressure to surrender. Though he was considered a “renegade,” his ability as a military leader and his commitment to his people was much admired by the soldiers who were sent to find him. Some non-Indian people of his time feared him because of his dignity and his unfailing belief in his people’s traditions.

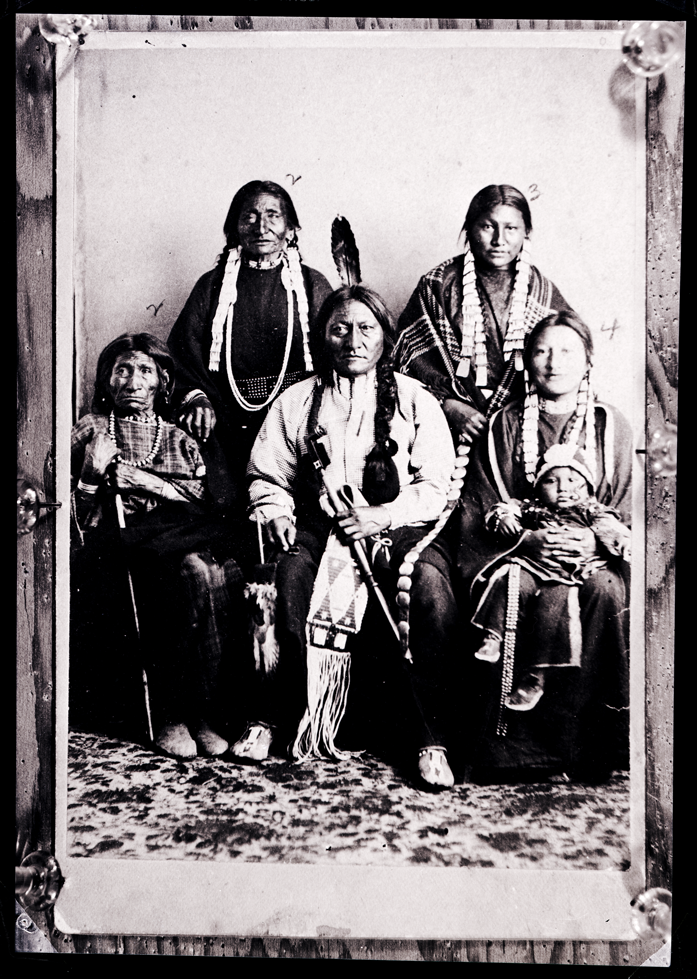

When he surrendered in 1881, Sitting Bull stated that he was the last of his people to surrender, but he also looked to a peaceful future for his children. (See Image 5.) He promised to teach his children to be friendly with non-Indians and asked that his son be educated in order to live a good life in a new tradition.