The Ghost Dance came to the people of the northern Great Plains during a desperate time. The Plains Wars had ended badly for the Lakota in 1881. The tribes were forced onto reservations where agents demanded that they give up their spiritual traditions. The bison herds had been reduced nearly to extinction. Food delivered by the federal government did not supply enough calories or nutrients to provide adequate defense against disease and starvation.

The Ghost Dance offered hope and healing to American Indian tribes around the West. The idea behind the Ghost Dance began in the 1870s in the region west of the Rocky Mountains. A Paiute called Wodziwob told his followers that their ancestors would return to earth. The people were to prepare for that time by dancing. His message was hopeful and joyful.

About 15 years later, the son of one of Wodziwob’s followers revived the Ghost Dance and brought it to the eastern side of the Rocky Mountains. This man, called Wovoka, had been raised by non-Indian Christians. Wovoka had had a dream in which he met with those who had died. In the dream he saw a world in which American Indian people lived in happiness; there was no disease, starvation or suffering. God spoke to Wovoka in his dream and asked him to follow his way. As Wovoka spoke to others about his dream, he became known as the Indian messiah.

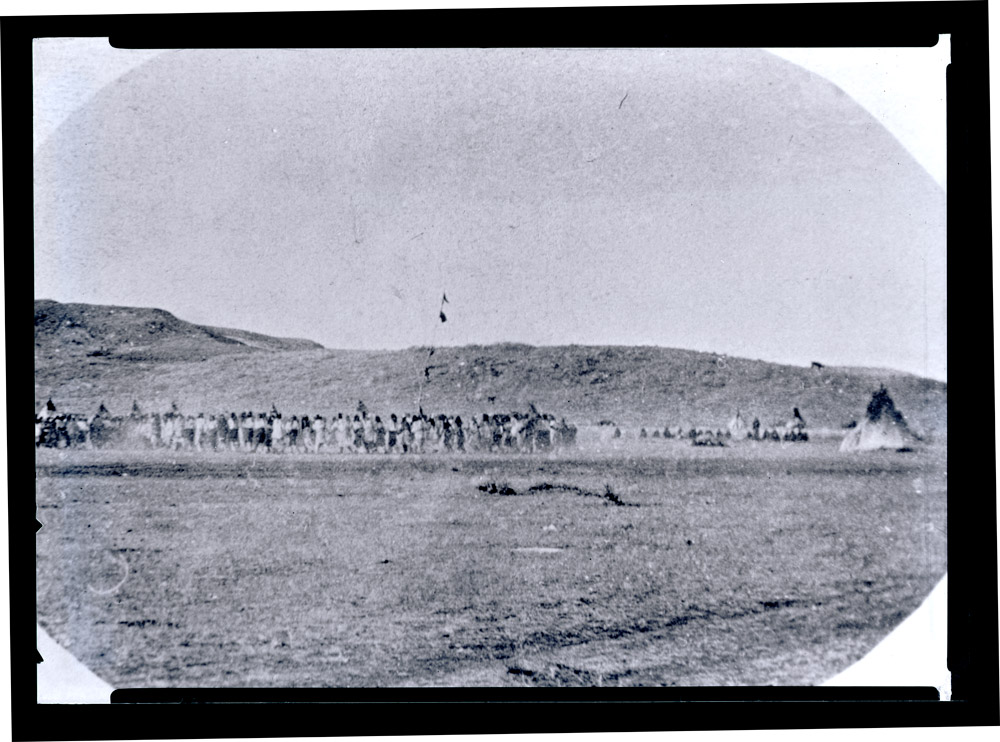

Dancing was part of the religious practices of the Ghost Dance. Followers of the Ghost Dance were supposed to dance every six weeks for five days and four nights. Dancing would make the promised events come to pass sooner. (See Image 17)

The Lakotas of Dakota Territory sent representatives to find out more about the Ghost Dance. Among these representatives were Kicking Bear and Short Bull. These men returned with a letter in which Wovoka emphasized the peaceful aspects of the new religion. In the letter, Wovoka wrote:

. . . you must not hurt anybody or do harm to any one. You must not fight. Do right always. . . . there will be no more sickness and everyone will be young again.

By this time, about 20,000 people were following the Ghost Dance religion. The Lakotas added another aspect to the Ghost Dance by wearing special shirts or dresses made of cotton cloth. (See Image 18) They believed that the ghost shirts protected the wearer from all kinds of danger, including bullets.

Not all the Lakotas followed the Ghost Dance. There were many who preferred the traditional religious practices and many who adopted Christianity. Some missionaries commented that the Christian converts on the reservations resisted the Ghost Dance. During 1890, the Ghost Dance reached its peak among the Lakotas.

Why is this important? While Christian missionaries tried to convert the Lakotas, federal reservation agents outlawed traditional Lakota spiritual practices. The Ghost Dance, however, presented the Lakotas with a form of spiritual expression that reflected their beliefs, traditions, and present needs. The Ghost Dance offered a powerful promise that the good life of the past would return and that all of the hardship of the present would disappear. The people who followed the Ghost Dance believed that they could make this promise come true by dancing.

The Lakotas believed in the peaceful message of the Ghost Dance, but the new religion raised fears among non-Indians living on or near the reservations.

Sources: Ghost Dance: http://plainshumanities.unl.edu/encyclopedia/doc/egp.rel.023#egp.rel.023. Joe Starita, The Dull Knifes of Pine Ridge: A Lakota Odyssey (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1995), 98-99. James Mooney, “The Ghost Dance Religion and the Sioux Outbreak of 1890,” 14th Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology of the Smithsonian Institution 1892-93, part 2. (available online at books.google.com)