Mandan Creation Narriatives

There are a number of accounts about the Mandan migration. Some accounts tell of the Mandan being created at the Heart River while others tell of a migration from the Gulf of Mexico along the Missouri, and from the Southeast. One narrative tells of when Lone Man (Mandan term for Creator) made the land around the Heart River, and he also made the land to the south as far as the ocean. He made fish people, eagle people, bear people, corn people, buffalo people, and others whose history was translated into accounts of the sacred bundles.

Origin Narrative Told by Foolish Woman, Mandan/Hidatsa

There are four written and recorded versions of the Mandan origin narrative. First Creator and Lone Man—Version 2—Told by Foolish Woman, Mandan/Hidatsa, at Independence on July 11, 1929, follows:

In the beginning the whole earth was covered with water. Lone Man was walking on top of the waves. He thought to himself, “Where did I come from?” So he retraced his footsteps on the top of the water and he came to a bit of land jutting out of the water. He saw a plant called “big medicine” that grows in the marsh two or three feet high with flat white blossoms that come out in the spring. One branch was broken and hung at the side. At the broken place he saw drops of blood and thought, this must be my mother. As he looked about he saw an insect called “Tobacco Blower” flying about the plant and he thought, this insect must be a father to me.

He thought to himself, “Where did I come from?”

He walked further on the water and saw in the distance an object that he found to be a mud hen. The First Creator came to the same place. “How do you come to be wandering about here?” First Creator said, “I have been considering that you and I should create some land.” Lone Man agreed. They asked the mud hen what food it had for its nourishment. The bird told them, “I dive under the water and there is land and I eat the dirt down there.” They said “Dive down and bring us a sample. Some time later the bird came up with a little mud. Four times it dived and still there was only enough to fill one hand. Lone Man rolled it into a ball and gave half to First Creator and kept the other half. He said.

“We will make a dividing point and leave a river and you may choose which side you will create.” First Creator chose the south side. Lone Man took the north.

First Creator made some places level, ranges of hills, mountains, springs, timber and coulees with running water. He created buffalo—made them all black with here and there a white one. He created Rocky Mountain sheep, deer, antelope, rattlesnakes—all the animals that exist here.

Lone Man created mostly flat land with many lakes and ponds grown with bulrushes and few trees. He created cattle—some white, some spotted, some red, some black—with long horns and tail, and the animals like the badger and beaver that live in the water and the duck and geese that swim on the water, also the sheep of today.

Then they met on the north side of the river and reviewed the creation they completed. Both believed his creation to be the better. They examined first what First Creator had made and Lone Man said the land was too rough. First Creator said, “No, I did this for the safety of the creatures. When they are in danger from a hard winter, they will have protection in the timber and shelter in the coulees. He showed him the tribes of people that he had made (the Indians).

“No, I did this for the safety of the creatures. When they are in danger from a hard winter, they will have protection..."

But Lone Man was displeased with First Creator’s work. He showed him how level the land was on the north side of the river, with lakes, scattered boulders and treeless, so that the eye could see far away. First Creator was dissatisfied. He said, “In the winter there is no protection, in time of war, there will be no place to hide.” “No,” argued Lone Man, “They can see the enemy far away and hide in the bulrushes beside the lakes. He pointed out the beauty of the cattle. First Creator found them too weak to pull through the winter, with too little fur, too long horns compared with the protection of the buffalo against the cold. So he disapproved of Lone Man’s creation.

It was agreed to let the people live first on the creation of First Creator then the generations to come should live on the cattle created by Lone Man. Lone Man’s cattle should drift back to the far east where he had created people, who should come westward later and inhabit the land with the first people.

Of the dirt from the ball some had been left over and this they placed in the center of the created land and formed a heart-shaped butte which they called “The-heart-of-the-land,” to be seen to this day near the city of Mandan near the Heart River. Still some mud was left over. This they took across the river opposite to Bird’s Beak Hill below Bismarck on the north side of the river, and this butte they called “Land.”

They wandered upon the land and one said, “I think I am older.” The other said, “No, I think I am the older of us two.” They laid a bet. Lone Man had a stick strung with a sinew to which goose feathers were tied at intervals. This he stuck in the ground. (If he drew it forth before the other was dead he must acknowledge himself defeated). Lone Man wandered off, and the next year when he came back to the spot he found nothing but a skeleton. The bow was worn and weathered. He came back from year to year. The fourth year there was not a feather left on his bow, and where First Creator lay, the grass grew tall. Lone Man said, “Why leave my bow any longer? He will never get up now!” He took his bow, sang a song, and it was as new as ever. As he walked away, First Creator got up, shook himself, and was fresh as ever. Lone Man looked at him and he was Coyote.

They separated again and wandered apart. Lone Man went on his way and thought, I have nothing to carry. If I had a pipe and tobacco it would be fine! He saw a buffalo lying down. As he approached, the buffalo was about to run away, but he called out, “do not run, it is I!” He asked the buffalo what it could do for him in this matter. The buffalo passed water and tramped about in a coulee and told him to return at this time of year and he would hear a sound and find his tobacco growing. Sure enough the next year he heard a buzzing sound and there was a tobacco plant growing with a tobacco blower buzzing about it. Buffalo instructed him that the best part grew next to the bud and to dry it he should lay it on buffalo hair taken at the shoulder and put it to dry in the sun. For the bowl he should use oak, for the stem box elder. This was meant to indicate that the land on the south side of the river was male, that on the north side female. “I have nothing to light my pipe with,” said Lone Man—“Go over there to an old man on the side of the hill, he will give you a light for the pipe,” said Buffalo. This old man was the burning lignite. Lone Man was on his way. The Mandan people originated at the mouth of this river way down at the ocean. On the north side of the river was a high bank. At its foot on the shore of the ocean was a cavern, - that is where the Mandan people came out. The chief’s name was Ka-ho-he, which means the scraping sound made by the corn stalks swaying back and forth and rubbing each other with the sound like a bow drawn across a string. Ko-i-roh-kte was the sister of the chief. The name means the testing of the squash seeds. When they plant squash, to test the seed they wrap the seed in dead grass and keep it moist. The brother’s name was Na-c-i. This is the name of a little animal the size of a prairie dog and quite a traveler, which has a yellow streak over the nose from cheek to cheek, but changes color in the fall. In this boy’s system was the spirit that travels far.

The Mandan people originated at the mouth of this river way down at the ocean. –Told by Foolish Woman at Independence, July 11, 1929

Somehow Na-c-i got up on the surface of the land. He went back and told his elder that the land below was not to be compared with that he had seen. He asked the people to come up and inhabit the earth. They found a vine hanging down and that was where they came up. A good number had already emerged when a young girl, big with child, insisted on coming out and she was so heavy that she broke the vine and fell back into the cavern...

Lone Man happened to come to their village and saw that these people were advanced, for they were tilling gardens. Lone Man thought “those are real people, I will manage to be born among them.” A man and a woman had a daughter who was a virgin. The father was a leading man in the village. Lone Man chose their daughter for his mother. So one day when they went to work in their gardens by the river bank, the girl went to the river to drink and there she saw a drowned buffalo drifting close to shore. Where the skin was broken she could see the fat of the kidneys sticking out. She drew the buffalo to shore, fastened it by the feet, and ate of the fat of the kidney. This was really Lone Man, and this is how she conceived by him. She came back and told her parents about the buffalo, but when they ran gladly to the shore, they could find no trace of it—only a loop tied to the bank. They thought no further about it, but as the months went by and they began to notice that she was with child. When the mother questioned the daughter, she said she had known no man and could not tell how she had got in this condition.

When the time came, the daughter delivered a baby boy. The father had not believed that the girl had met no man, but as the child was born, there was a light which shone through a hole in the sky. From year to year, the boy grew stronger and wiser. He was looked upon as unusual. He grew faster than most children. As he grew to manhood, he was looked upon as a leader. In times of hunger, he caused the herds of buffalo to come near the lodges so that they had meat to eat. When they planted corn, he would cause it to rain so that the land had moisture and the people had plenty of corn.

“When they planted corn, he would cause it to rain so that the land had moisture and the people had plenty of corn.”

There were evil beings born into the tribe where he was and when they grew up, they wanted to rule the village and they schemed against him to bring about his destruction. He made a boat called “self-going” that went by itself. They would get in this boat and cross over to an island, whose chief was named Ma-ni-ke. Only twelve people could go in this boat, if more went the trip was unlucky. They would carry offerings, as between the mouth of the river and this island there were obstacles to contend with. In one place was a whirlpool, in another the waves were high. They offered sacrifices in order to escape the whirlpool and calm the waves. At the island the chief would give them beaked shells of many colors in exchange for presents. These shells they used for earrings. Mata-pahu-tou—Shell-nose-with—is the name the Indians give these abalone shells.

One day twelve men were going on a journey, then Lone Man came along and jumped in the boat. They tried to make him leave, but he said he had heard so much about the feasting on the island that he wanted to go along. When they reached the whirlpool, Lone Man was asleep. They were afraid and woke him. He got up, reached out and picked up the objects that had been offered in sacrifice and said, “These are just what I want!” Then he took his bow, smoothed it, and commanded the water to be still. Then he stilled the whirlpool and the high waves. The people said, “When we land on the island, they people usually get up a feast and make us eat everything they set before us and nearly kill us.” So he took a reed by the river and with a stick ran through the points and inserted the reed through his system so that as he sat at the feast, it would reach down to the fourth strata of the earth. He ordered the men to eat only what they wished as the plate was passed at the feast, and let it come last to him and he would empty the whole down the reed. So it happened. There was a great feast. They were brought into a great lodge nearly filled with food and were not allowed to leave anything. They sat about in a half moon shape and ate. When all had eaten their fill they placed the pot before him and he emptied its contents down his mouth. In no time they had cleaned out the whole works.

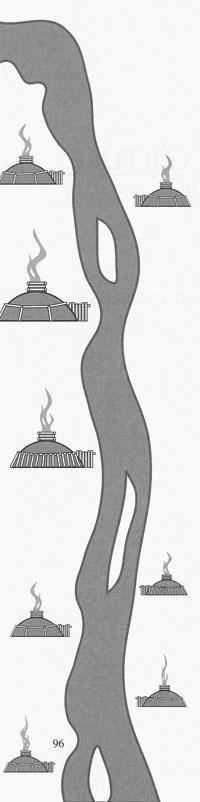

As they left the island, the chief said, “In four years I will come and visit your village.” He meant to destroy them with water. Lone Man told the people to weave a barricade about the village and hold it together with young cottonwood trees. He brought all the people inside the barricade and when the water came, it only went as far as the cottonwood tree barricade. In the water there were what looked like people and those inside the barricade would throw offerings and the people in the water would pass the shells over. (Beckwith, 1937:7–13)

Origin Story Related by Wolf Chief

Wolf Chief, Hidatsa, secured this information from his Mandan father-in-law, Red Roan Cow, Nuptadi Mandan Chief. For other versions of the creation stories see Martha Warren Beckwith, Mandan-Hidatsa Myths and Ceremonies “Memoirs of the American Folk-Lore Society,” Vol. XXX11 (1938), pp.10–11; Maximilian, Prince of Wied, Travels in the Interior of North America, 1832–1834, in Early Western Travels, ed. Thwaites, XXIII, 312–17; and Catlin, Letters and Notes on the Manners, Customs, and Conditions of the North American Indians, I, 279–80.

A long time ago the Missouri River flowed into the Mississippi River and thence into the ocean. On the right bank there was a high point on the ocean shore that the Mandan came from. They were said to have come from under the ground at that place and brought corn up. Their chief was named Good Furred Robe. He had one brother named Cornhusk Earrings and another younger brother called No Hair on Him or Head for Rattle after the gourds. They had a sister named Corn Stalk.

In the early time when they came out of the ground, Good Furred Robe was Corn Medicine, and he had the right to teach the other people how to raise corn. The people of Awigaxa asked him to teach them his songs so as to keep the corn and be successful in growing their corn. Good Furred Robe also had a robe which, if sprinkled with water, would cause rain to come.

When they came out of the ground, there were many people but they had no clothing on. They said, “We have found Ma’tahara.” That was what they called the river as it was like a stranger. It is also the word for “stranger.” They went a short distance and planted corn, even though they were naked. Then they moved north, and no one knows the number of years they stopped at the different places. At last they came to the place where the river flowed into the ocean. When they came to the mouth of this river, they saw people on the other side who could understand their language and they thought they were Mandan too. The village on the other side had a chief whose name was Maniga. It was a very large village.

At last they came to the place where the river flowed into the ocean.– Related by Wolf Chief, Hidatsa, 1938

While they were stopping there, they found that the people on the other side owned bowls made of shells. At Good Furred Robe’s village they would kill the rabbits for the hides. They also killed the meadowlarks for the yellow crescents. They took them to the people of the other village to trade for shell bowls. They would also take the rabbit hides painted red and trade for the shells.

Good Furred Robe also owned a boat that was holy. It could carry twelve men. Each time they wanted to trade in the other village, they would take the red rabbit hides and the yellow meadowlark breasts and float over. There was a rough place in the middle, and they would drop some of these objects into the water, and then the water would calm.

All during this time they had enough corn to live on, but nothing is told in the traditions about their clothing. They continued moving up the river until they came to the mouth of the Missouri River. They saw many trees on the Mississippi River and decided to go across and live on the Mississippi. They stayed in that country for three or four years, all the time planting corn along the river. They said, “We have discovered fine evergreen trees, and we have called them medicine trees since that time.

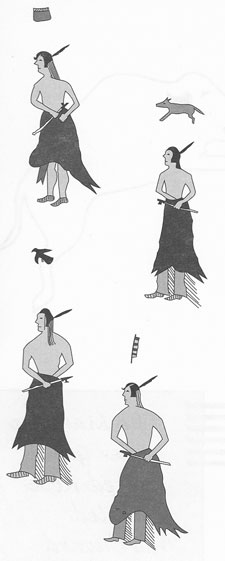

There were no bows and arrows in those days, and one of the men made a bow and arrow, practicing with them and picking out sharp bones with which to tip the arrows. He also found the sinews that would stretch the bow. We do not know if they were eating meat or not at that time. There were many elk, deer, and beaver on this river, and that is why they called it Good River. At that time they found a dead buffalo in a mud hole, and one of them said that they ought to take the hide off and cut it into a long string to catch deer with. When they took the hide off, they cut the strings and twisted them to dry. Then they made a loop on the end. They would go out and find deer trails to hang it in to catch the deer. They made many of these snares and set them out in many places. They would find some dead deer and even some elk hanging there.

After they learned how to do this, they had plenty of meat to eat with their corn. They stayed at that place for over ten years. It was at this time that they learned how to use the bow and arrows tipped with bone, to kill smaller game.

It was at this time that they learned how to use the bow and arrows tipped with bone, to kill smaller game.

Again they moved from there farther up the Mississippi River until they found a place where there was much timber but the surrounding land was flat. They found a flat place where the timber was not so thick, and there they lived for six years. At that time they called themselves Nu’itadi, meaning “from us.” Some of them were called Nup’tadi (no meaning); another group was called Awi’gaxa (no meaning). One of the latter two bands moved from the others under a chief named Four Bulls and came to a place where there was much timber. The village after the split must have been in the western part of Minnesota not far from Pipestone.

They traveled southward then until they came to heavy timber and had a big village there. (These villages were named in the Okipa ceremony, but the language used was unintelligible to the listener, as it was an old dialect. The translation was a part of the secret lore, which passed with bundle sales.) While there they learned more about bows and arrows and could shoot even beavers and other game. Then they had plenty of food. Again they traveled on through the deep timber and had another village, staying there for four years. The earthlodges at that time were of the eagle-trapping type with grass and dirt covering the sides.

When they stopped there, a man went out looking for game and followed a creek. He saw some mud sticking out of a hill, and there was a spring at that place. The mud was sticky; he took some of it out and carried it away a short distance. He left some of it flat on the ground to dry. When he went back where he had left the mud, it was hard except that there was one crack. He thought that there should be some use for that mud. He thought, “I will get some sand and mix it with this mud and leave it again. It might be of some use.” Then he went home again. When he returned, the mud was still cracked. He thought, “If I crack some stones and crush them fine to mix with the clay, It might be better.” He found some hard stones and put them in the fire to burn four days. Then he crushed the stones and took the material to the place where the clay had been left. He mixed the clay with the crushed stone, shaped it into a pot, and left it in the sun to dry. Next day when he went back, he found that it was hard and could be used. He made many more; some he made into the shape of spoons. (Spoons have never been found in Mandan archaeological sites, whereas pots are abundant). From that time they had pots. After that they made large ones and baked them to cook in. The Mandans were the first to discover pottery; the Hidatsa and other people learned the art from them. The mud was a special kind, and it was hard to find. Later they found this clay around the flint they took out of the tops of hills west of the Missouri River.

They stayed there for more than ten years, for there were many animals suitable for food as well as good corn grounds. During this time some of the young men were looking for game, and they came out of the timber. They could see the flatland for a great distance, so they thought that they would move. At first they did not come completely out of the woods but stayed on the edge.

When they came out of the timber, they had another large village again. They stayed there a long time, for there was much game and they had their gardens in the timber.

When they had the village there, it happened that they had a dry year. The people who called themselves Awigaxa made a feast, and they had some of the women paint their faces and wear geese on their heads. (The Goose Women’s Society was founded by Good Furred Robe, and the Corn Bundle-owner was singer for this society.) First Creator and Lone Man came at that time. They asked these people where they came from, and they replied that they had come up from under the ground and that they had traveled around much since then. The two men said, “You seem to be getting along well here. We came from the west bank of the Missouri River. We discovered some prairie dogs in a village there, but we changed them into humans. We showed them how to put on the Buffalo Dance, but we see now that we would rather have you people here put on that ceremony, for you would be more careful about giving the dance.”

"We showed them how to put on the Buffalo Dance, but we see now that we would rather have you people here put on that ceremony..."

Then the two men walked off and returned to the prairie-dog village they had changed into humans. First Creator and Lone Man had made the dance for the prairie dogs and, when they came back, they saw that these people were not fit to give the dance, for they had left the drum in an ash pile. They thought, “These people don’t appreciate the dance, for they are not the right kind of people to begin with. It would be much better to take the Buffalo Dance from them.” The two men took the Buffalo Dance away from the prairie dogs and gave it to the Mandan. They gave the prairie dogs a curing ceremony instead. The Arikara were the prairie-dog people. They have the Prairie Dog Curing Medicine yet. First Creator and Lone Man came back to the Mandan village and said, “We are going to show you the Buffalo Dance.”

They said, “What is it?”

They replied, “It is a good thing for you, and any time you have a shortage of food, you will pray for food. This way it will increase your people and bring you plenty of food.” They showed these people how to give the ceremony, paint, and dress.

They thought, “How will we paint to make them good-looking? We might use some of the color of the snakes; they look nice. It is not a real snake but the worm on the chokecherry bushes. Between the shoulders they grow a hook. We will have that represent the mask and take that color for the buffaloes. The hook behind will be the buffalo horn and the branches will be the branches of the worm nest.”

The people inquired how they would fix up that way and Lone Man said, “Go out and kill a buffalo; take all the flesh off the skin and bring the hide to me.” The people went out and killed a buffalo and brought the hide to the two men. They called one of the young men to stand before them. They took the horn off with the horn core removed. The young man had long hair hanging down. They put the horn on his back with the brush over it, reaching over his head and hanging down nearly to the ground. They painted him on the chest, legs, and arms with red, black, and white. All this was representative of this bug in color. When he was painted, he was very beautiful.

At this time they had a hide for a drum. They wanted to practice the songs that belonged to this drum, but the drum was not very solid. It would sink into the ground and soon wear out. Lone Man was doing the drumming, and he said to First Creator, “You show them how the dancing is done, and I will do the drumming.” Lone Man sang the song, and First Creator danced, stretching his arms out. He danced and showed the painted man how to dance.

Lone Man said to the people, “You must not touch this drum, for it is very holy. We are going out to look for another drum, and will be back after a while.”

They went out, and after a while they came back with a badger. Even before they had the Buffalo Dance, Lone Man had a flat stick. Before he touched the badger, he held the stick up, the badger sank into the ground.

They said, “The badger has no strength and it is not suitable.” They went to the beaver, but, before he ever hit the beaver, the animal sank into the ground. Each time he held his stick up, the earth shook. They went out again and came to a turtle. They asked him but the turtle replied, “I have no strength or power. I would rather that you went to the big turtle that is in the ocean. He would be a better drum, for his life will be so long that he will last forever. He will be better for the drum.” When they came to the shore, they found a large turtle; it was brown. They talked to the turtle saying, “We are looking for a drum to use in the dance, and now we need you for the drum.”

Each time he held his stick up, the earth shook.

The Turtle said, “That is all right. I do not think I can go myself, but you can look me over and then make one yourself out of a buffalo hide. When you fix it that way, I will be there just the same, for you will be taking the shape of my body. If you do that, I will last forever.”

When they returned, they killed a buffalo, took the hide off of the bull, and made a turtle. They made the legs out of oak and covered it with a hide from which the hair had been removed. Then they painted the outside with red paint. They finished the turtle, and in two days the hide was all dried up. First Creator said, “We must pick out a young man to dance in the costume; you show him how to dance.” Lone Man made a motion as of striking the turtle. At the same time there was a noise as if the earth were cracking and dust came up, but the turtle was not driven into the earth like the other animals had been. Then Lone Man said,” That is the kind of drum we want; it will last forever. After this if any of you people dream of this dance or have a dream in which it is a part, then you must put up this dance. We are not going off right away but will be around near by.”

He said, “When a young man is dancing, he may want to smoke the pipe. If you feel like smoking it, fill it up. I made it out of a green buffalo tail, bent it on one end to hold the tobacco, and filled it with sand until it was dry. The men with the buffalo heads must not touch the pipe. If he wants to smoke, you hold the pipe while he smokes.”

About this time, Good Furred Robe, who was always traveling, found a red spot and wondered what it was. Going there, he saw that it was a stone. He thought that it might be a good thing to make a pipe from. Up to this time the people had used black stones for smoking. He brought the red stone back. He thought how in the Buffalo Dance they used the buffalo tail and how it would be a good thing to fix up the red stone pipe and let them use that. He made a pipe with no elbow; the hole was in the end.

They had another Buffalo Dance, and one young man danced. At that time Lone Man came back. God Furred Robe took the pipe to him and said, “I saw you using the buffalo tail, and I think this is better.” Lone Man said, “It looks pretty, but I am afraid of it, for it is the color of human blood.”

The Goose Women had put up a feast because the fields were drying up. Good Furred Robe took the pipe to them and said, “I have a good pipe here; it is a nice color. You should use it instead of the one you have that is not pretty.” They said, “We are afraid of it because it is the color of human blood.” The people were wondering where he had found the red stone, and he took some of them to the place and showed them where he had found it. They saw some of the pretty stones and made a few pipes for their personal use. (Bowers tried to claim the pipe stone quarries by this story, but some people did not believe it. Mrs. White Duck has Good Furred Robe’s skull, but some of the younger men do not claim it because they are not familiar with this old story.)

Later three men were traveling around a great deal, and each time they would get farther and farther. One time they came to the Missouri River and saw timber on each side. They reported this to the people, who thought that it must be a branch of the river they passed farther to the south. They decided to move from their village toward the river. They came to the Missouri River at what they called White Clay Creek. (This is White River, which enters the Missouri River below Chamberlain, South Dakota.) It is below the Cheyenne River today. The camp was just opposite that river on the east side.

They built a camp there, and after three years the Awigaxa disappeared. They thought that the Awigaxa must have gone up the Cheyenne or White Clay River to the west. Two years afterward, about twelve families of the Awigaxa came back.

They built a camp there, and after three years the Awigaxa disappeared.

When they came back, they said, “They sent us back because the people out there do not think you know the Corn Medicine rites. They asked us to teach them to you.”

Lone Man came back. He related his dream to Lone Man, who said, “That is all right. You should try to put up the ceremony.”

In the dream he had seen the four turtles. They had eagle feathers on their heads, but Lone Man said, “It would be hard for you to save that many feathers. You will have time to save some. Take your time saving all those feathers. If you think there are enough for four turtles, call me, and I will hear even though I am far away.”

He saved all the feathers, knowing that it would take him a long time. In three or four years he had the necessary feathers, and then he called Lone Man. They made three more turtles just like the other one they had fixed before on the pattern of the ocean turtle.

When the two finished the turtles, they arranged them in a row, first the small one, then the two medium-sized ones, and then the large one which had been made first. Lone Man said, “You should give them what you can.” It was the speckled eagle feathers that he was giving them. When he came to the last one, thinking it would like the calumet eagle’s feathers best, he decorated it with those feathers. The one at the head said to the man, “You did not give me the right kind. That feather I do not like. For this reason, I am going back to the water.”

They tried to hold him but could not. He walked away and went in to the water. They called to Lone Man to help them. He came back and walked toward the turtle in the water. He took his lance up, sang his song, motioning with it at the water which ran apart. He could see the turtle in the water. He said, “They gave you the best of all. What is the matter?”

The turtle said, “That is all right.” Then the water covered over the turtle again. I was never at the place (Note: Crows Heart has been to the spot and says that it is upstream from the mouth of the Cannonball River at an old village near Butte without Hair on the east bank. This is probably the Shermer Site. There is another Butte without Hair directly opposite on the west side of the Missouri River.) where it went into the water, but it was about opposite where Fort Yates now stands. The place or village is called “Where Turtle Went Back.”

When Lone Man saw that the turtle was in the water, he turned around and walked back. Then they started the ceremony, and Lone Man said, “It is all right, for there are three left.” They selected a big lodge and by that time the buffalo masks were taken inside. Lone Man was there and the Ho’Kaha, a tall blue-gray bird with a long bill and a short tail (probably the heron), was in its place.

There were forty families that went out to White High Butte, now called Sheep Butte. These people separated from the others over in the woods before the Mandan reached the Missouri River. There is a river, which runs north at Minot, North Dakota. There is a high butte up there called White High Butte. It is to the north of the Turtle Mountains. Their chief was Four Bulls, as you recall earlier in the story. Four Bulls and all his people had moved up there, building villages along the way until they reached this spot. Sometime in the spring they were living there. The Indians would make a trap of brush and woven hair and put bait inside. The birds going inside were taken. They birds were fat and good to eat. In the spring a young man, not knowing any better, pulled all the feathers off one of the birds and stuck one of the feathers through the bird’s bill and nostrils. There were four medicine men there named Spring Buffalo, Winter Buffalo, Middle of the Summer Buffalo, and Autumn Buffalo.

At the time of the young men in the village went out and caught young buffalo calves and brought them into the village. It was customary to blow up the entrails to dry. The young men blew up some, dried them, putting them over the calves’ heads and telling them to go. When the Lone Man created these birds, he had them represent the water by the little spots under their wings. The four medicine men were angry at the way the calves were treated. The birds were angry too. They caused rain to fall for a long time. The water kept rising, getting nearer and nearer to the villages. The people called for Lone Man, saying that the water was coming and covering them. He fixed up the sticks in a circle with a water willow around them. When he finished, he took all the people of the village into the corral around the village. The four medicine men changed into buffaloes. They had a younger brother who was the magpie.

When the water began to cover the village, they started to swim to the Missouri. Magpie had a string around his neck, which held the corn. One of the buffaloes was exhausted and said, “In the future there will be plenty of buffalo here and people can come here and hunt them.” Then there were three. After a while one more of them was exhausted, and, before sinking, he said, “In the future there will be plenty of buffaloes if the people come here,” and he sank.

A third one became exhausted, and he said, “In the future if people come here they will find plenty of buffaloes,” and then he sank. There was one buffalo left, and he was swimming along. He saw a high butte in front of him. It was Birds Bill Butte (also known as Eagle Nose Butte) and he swam toward it. He was completely exhausted when he reached the butte.

Back where Lone Man had the people in the corral, they were saved by the power of the corral. He said, “This cedar and corral is my protector. From this time on, you will always have it.” The Mandan under Good Furred Robe traveled northward along the Missouri River until they reached the Heart River, where they joined the others whom Lone Man and First Creator had created at that place. At this time the flood was coming. These people built a large corral south of the Heart River on Eagle Nose Butte where they also were safe from the flood.

The Mandan under Good Furred Robe traveled northward along the Missouri River until they reached the Heart River. – Wolf Chief, Hidatsa, 1938

The Awigaxa did not have the turtles and cedar to protect them, for they had the Corn to worship. While living on the White Clay Creek and Cheyenne River, the Awigaxa became separated. The group not having the Corn ceremonies was lost while making sinews near the Black Hills. Before the flood, the others came back to the Missouri River, for the river bottoms were not so large where they had been and not much corn could be grown. They built large villages at the mouth of the Cheyenne, Moreau, and other streams until they reached the mouth of the Grand River. At this time they had corn rites, but there is no mention of the Okipa or the sacred cedar.

When word reached the people who were living at the Grand River that a great flood was coming, they must not have had a sacred cedar since those who remained in their villages were drowned while those who escaped to the Rocky Mountains were saved. After the waters had retreated, those in the mountains planted corn out there, but the seasons were too short and the yields were small. The people wanted to return to the Grand River, but other people were living there. Scouts sent out reported that the other Mandan who had lived on the west bank of the Missouri near Painted Woods had left their village, the ruins of which were still standing, to seek shelter in a large corral built by Lone Man near the Heart River. The people decided to move from the mountains and built a village near Painted Woods at a spot where there was much wood.

While living in this village called Awigaxa, Lone Man and First Creator came along and found them. They came along when the water was high during the spring floods and told the people that higher floods might come and that they should have something to protect them. Some of the people thought it would be easier to escape to the mountains, since it took so much goods to perform the Okipa and the rites at the sacred cedar. Others thought that it was more costly to travel so far. Still others thought that the cedar would be useful for other purposes. Lone Man sent a young man a dream in which he saw the buffaloes dancing at the sacred cedar, and the old men interpreted the dream to mean that they should give the Okipa. Some thought that goods should be paid in large quantities equal to the inconvenience of moving to the mountains, and from this time the Awigaxa were the most liberal of the villages in supplying goods for the ceremonies. Lone Man and First Creator came and taught young men who were brave and intelligent how to impersonate the different characters. There were more people in the ceremony than when the other Mandan were taught the ceremony while living far to the southeast.

Even the Awaxawi and Awatixa who were living on the Missouri at that time came to make offerings and to fast. The Hidatsa must not have come south yet from the place where they had gone to escape the flood, for nothing is said of them in the old story. After the Okipa ceremony was given, the people were very lucky because there were so many more gods to protect them. Because the people were so lucky, when the wood was exhausted at one place, they built another village near by. No bad luck came to them until smallpox was brought in by the white men. (Bowers, 1991, pp. 156–163 reprint)

Mandan Lifeways

The Mandans moved very little since prehistoric contact. Their basic culture changed very little except for changes when the horse and European trade goods were acquired. They were semi-sedentary having rich material wealth setting them apart from the nomadic buffalo hunters of the plains.

Extensive archaeological studies correlate traditions of both the Mandan and Hidatsa migrations and residence on the Missouri River. Their economy was based on agriculture and hunting. They hunted buffalo and small game on foot. The Mandans planted mainly corn, beans, squash, and sunflowers on their bottomland farms. They were a people who consistently planned ahead and who stored their agricultural products to sustain them during the lean years.

They commonly transmitted sacred property through the matrilineal line. The Mandans preserved their ceremonial structure with minor variations after the smallpox epidemic. The clan system and age-grade organization was modified to meet the new conditions of a reduced population.

Although each permanent Mandan village was a separate economic, social, and ceremonial unit, the villages were not entirely independent. The turtle drums, which were considered the most sacred objects of the tribe, were held by the Nuptadi band of East-side Mandan. The sacred cedar in the center of each village was a symbol of village unity, and the Mandan considered the turtle drums a symbol of tribal unity. The other villages were able to borrow them for ceremonial purposes.

The Mandan played an important role in the growth of Plains culture. Because of their central position in the Central Plains, the high development in trade for agricultural products with their neighbors, and the admitted borrowing by the Hidatsa of many significant elements of their culture. They were a sustaining force of Missouri River economy and culture.

Dwellings

The Mandan earthlodge villages were comprised of a mass of circular houses from forty to ninety feet in diameter, closely crowded together. The houses were of earth with a smooth coating of pounded clay on the top, where most of the inhabitants were usually stationed. Before each house was a scaffold, fronting the covered entrance. These scaffolds were six feet high, twenty feet long and ten feet broad and were used for hanging up corn and meat to dry. They had a good floor, which was covered with drying beans. The stage for drying corn and meat was as follows: posts were set up on the scaffolds themselves, across these rafters were laid, and upon these cross rafters or poles the corn, meat, and sliced squashes were hung. Before almost every house were one or more poles about twenty feet high, to which images of the gods or sacrifices to them were attached.

to thirty bushels of beans and corn where it kept for several years.

(Photo by Gwyn Herman)

The sedentary character of the Mandans and the fact that they practiced agriculture led to the development among them of several culture features not found among the purely hunting tribes. In common with most sedentary tribes they made use of caches or storage pits. Henry gives a description of them saying that, in the fall after harvest, the corn was dried, shelled, and put in deep pits. These were about eight feet deep, with a mouth just wide enough for a person to get in; the inside was hollowed out larger and the sides and bottom were lined with straw. The cache contained twenty to thirty bushels of beans and corn where it kept for several years. (Will, Spinden, p. 110)

Marriage Customs

The parents arranged marriages among the Mandan, though this does not mean that the young people’s wishes were disregarded. Divorce was not difficult. Elopement even of married people did not cause much of a stir unless both parties had children. A man who lost his wife by elopement would usually receive gifts from the relatives of the man who had taken his wife. He was expected to give his unfaithful wife fine new clothes and a horse, to show that he was above jealousy over a woman.

Marriage ceremonies were complex and depended on the social status of the families involved. The Mandan, with their long history of stable life, had what amounted to class distinction. Families who owned important medicine bundles and rights in ceremonies were of importance to the tribe as a whole. A wedding of the highest order involved a ceremony in which the groom gave away many valuable presents to people owning rights in this father’s bundle. The bride’s parents gave the young man an albino buffalo skin that at the end of the ceremony was disposed of according to which bundle was owned by the father.

There were distinct words for the different kinds of marriage. Another class of marriage was the groom’s father presented the bride’s parents some horses. If the bride’s parents approved of the marriage, they gave her the horses and she gave them to her brothers. Her brother then gave her an equal or greater number of horses, which she presented to her father-in-law. Then the girl’s mother and her brothers’ wives prepared a feast that they took to the groom’s lodge and left there. His relatives feasted with the young couple, and the women among them brought presents that were picked up by the bride’s female relatives when they came back for the empty pots and bowls after the feast.

The Kinship System

Mandan clans were organized groups and elected a leader who acted in an advisory capacity, usually an older person who had been successful in warfare or in hunting. The clan was a property-holding group. It was the duty of the clan to assist its own members, to care for orphaned children and its old people having no blood children. Older people were invited to be fed and clothed by younger members of their own clan. The clan was the medium for the transfer of property when a family died without leaving descendants.

The social structure of the Mandan was based on clan membership. The Mandan and Hidatsa are the only tribes in North Dakota who have a two-part hereditary division. The Mandan and Hidatsa members were related by blood, clan, and marriage.

The Mandans described their groups or moieties (a moiety is a combination of clans) as “East side” comprised of seven clans: Prairie Chicken, Speckled Eagle, Bear, Red Hill, Crow, Badger, and Bunch of Wood Clans; and “West side” consisting of six clans: Waxi’kEna, Tami’siK, Tami’xixiKs, and three extinct clans. The terms “East side” and “West side” referred to the positions the members took in the ceremonial lodge during the Okipa ceremony. The East side clans erected their side of the lodge and placed yellow corn in each post hole. The West side clans erected the west side of the ceremonial lodge and placed small mats of buffalo hair in the central post holes of their side. The Okipa, or ceremonial lodge, occupied a position on the north side of the village open circle, with the entrance facing the sacred cedar. All clans participated in the construction of the ceremonial lodge.

Before the smallpox epidemic of 1837, the moieties could not marry anyone belonging to the same moiety. Moiety also decided the division of buffalo killed in the old-time way; each had a leader for this activity. There was considerable rivalry between moieties in seeking war honors.

There were thirteen clans. Of the thirteen clans, nine have become extinct. The WaxikEna and Tamisik constitute one moiety and the Prairie Chicken and Speckled Eagle make up the other moiety. The major bundles of the Okipa ceremony were held in the WaxiEna Clan, which also owned the sacred cedar Lone Man shrine and controlled the Okipa lodge and sacred turtles. (Bowers pg. 45–57)

Kinship terms applied to members of the biological family who also were a part of clan and moiety groups. The entire tribe was classified as relatives and treated as such.

Each village was divided into a series of matrilineal (inheriting or determining descent through the female line), exogamous (marriage outside the tribe), nontotemic clans grouped into moieties (one or two units into which a tribe is divided). Each clan was composed of one or more lineages that were closely associated with the lodge groups. In Mandan theory the lodge group was based on matrilineal descent and matrilocal (residence with the wife’s family) and consisted of several families held together by women.

Lodges belonged to the women occupying the lodge. The lodge holdings, also belonging to the female, included the corn scaffold, storage pits, cooking utensils, bedding, dogs, harnesses, mares and colts, gardens, and gardening equipment. Geldings and stallions belonged to the men.

Ceremonial Life

Mandan ceremonial life was involved with medicine bundles. Each bundle was owned by a small group of individuals within a clan, and was inherited or transferred within the clan. When a bundle was transferred, a feast was given in its honor, and feasts were also given to the bundles at other times to increase their power. The bundle ceremonies were prayers to the particular Supreme Being involved in the bundle, for those favors over which they had control. Individual Mandan men also owned bundles based on visions, and these could be transferred, but never became established as to tribal importance. (Schulenberg, 1956:51)

In 1832, Catlin was privileged to witness the four-day Mandan ceremony called Okipa, which included fasting and self-piercing. The Okipa was a reenactment of events from the tribe’s past. It took place in the Okipa lodge and in the open space in front of the lodge. The Okipa was given in fulfillment of a vow based on a dream. Clan membership and bundle rights determined the role of the main participants. The purpose of the ceremony was to secure plenty of buffalo and well being for the village.

Their sacred bundles fall into two categories. They are the hereditary tribal bundles, and personal bundles. Great value is placed on those bundles and ceremonies that were instituted in very early times. These included the Okipa, founded by Lone Man and Hoita, and Corn ceremonies, founded by Good Furred Robe. (Bowers)

The Mandan system of bundle inheritance shows evidence of change. Certain bundles and ceremonial rights, traditionally inherited through the clan and more specifically from the mother’s brother, such as the Okipa belonging to the WaxikEna clan and the Shell Robe Bundle of the Prairie Chicken clan, showed a tendency to change to a father-son inheritance of the Hidatsa pattern. The eagle-trapping lodges were still inherited through the clan as late as 1929, but the associated bundles had changed from clan inheritance to father-son inheritance after 1875. The system of inheritance was more flexible than for the Hidatsa, with whom they were intimately associated. The Mandan parents often selected their daughters’ husbands and gave them preliminary assistance in ceremonial matters. The sons and daughters of a household usually purchased the parents bundles collectively and designated one, generally the oldest son, to be the custodian. A family having only daughters sold to the son-in-law provided he had been successful in warfare and had removed the mother-in-law taboo.

Hidatsa Creation Narrative

There are three Hidatsa bands each having their own origin narrative. The following is the origin narrative of the Awaxawi Band.

The land was then mainly under water. First Creator was alone and wandering about by himself. He thought that he was the only one when he met another person named Lone Man. They discussed their origins. Lone Man concluded that he came from the western wheat grass, for in tracing his tracks he saw blood on the grass, and that his father was the Stone Buffalo, an earth-colored wingless grasshopper, for he saw its tracks near where he was born. First Creator did not know who his father and mother were but he thought that he had come from the water. The two men undertook to learn who was the older; Lone Man stuck his staff in the ground while First Creator lay down as a coyote. Years later Lone Man returned to the place where coyote was lying and, seeing the bones scattered about, took up the staff, whereupon First Creator came back to life and was declared the older.

First Creator and Lone Man decided to make the land inhabitable and, seeing a goose, mallard, teal, and red-eyed mudhen, they asked the birds to lend assistance by diving below for mud. . . . Goose, Mallard, and teal failed; only the mudhen succeeded in bringing earth from below. Lone Man divided the earth and gave half to First Creator.

First Creator made the lands on the west-side of the Missouri from the Rockies to the ocean while Lone Man made the land on the other or east side, each using half of the mud brought up by the mudhen. First Creator made many living things later occupying the land and from the mud left over he made Heart Butte. Lone Man made his side flat and with the mud left over he made Hill, a small butte north of the present town of Bismarck, North Dakota. He made the spotted cattle with long horns and the wolves.

First Creator caused the people who were living below to come above, bringing with them their garden produce. The people continued to come up, following a vine, until one woman heavy in pregnancy broke the vine.

When first encountered, Lone Man carried a wooden pipe but he did not know what it was used for. First Creator then ordered Male Buffalo to produce tobacco for Lone Man’s pipe. (This act explains the use of pipes in the various ceremonies, which later were introduced, and the concept of tobacco as being sacred.)

First Creator decreed that people in seeking a living would scatter into small groups all over the land and would fight. (This degree established the various bands and linguistic groups.)

Because the spotted cattle could not stand the cold winters and the wolves sometime went mad, First Creator did not think they should be kept. So the spotted cattle and the maggots around a dead wolf, representing the white people was thrown eastward across the waters until a later time when they would return as the white men and their cattle. Finding the land to the east too level for shelter from storms, they roughened it with their heels to form land as it is seen today. The people dispersed over the land into tribes and the two men visited them in their villages and camps. At this time the people, whom we know as River Crow, Hidatsa, and Awaxawi, moved northward toward Devils Lake and lived together as a single group. There were many lakes where they lived at that time.

Finding the land to the east too level for shelter from storms, they roughened it with their heels to form land as it is seen today.

Hungry Wolf of good reputation lived in the village with a younger brother named High Bird. Young men would line up along the path by the young women getting water to ask for a drink. When water was offered one, it indicated that she was fond of him. High Bird’s friend, an orphan, lived with him. Hungry Wolf’s wife offered High Bird water; he refused it because she was his brother’s wife and she became angry. She told her husband that High Bird had attacked her. Although witnesses denied the charge, Hungry Wolf did not believe them. He announced that he was organizing a war party and High Bird and the orphan decided to go along. To cross a large lake, forty bullboats were made to carry the eighty men. They traveled four days by water. High Bird as scout brought in an enemy’s scalp for his brother, but Hungry Wolf ordered his party to leave quietly by water while his brother slept, leaving him no means of reaching the mainland.

Hungry Wolf called back to his brother that the Water Buffalo, his “father,” had ordered him to do this. His gods, who ate those who assisted Hungry Wolf, protected High Bird. (The narrative here introduces the sun as a supernatural guardian and also as a cannibal. The concept of the sun as a cannibal appears throughout Hidatsa sacred mythology.)

Hungry Wolf called back that if High Bird crossed the water, the Sharp Noses would kill him so High Bird matched the supernatural powers of the Sharp Noses with that of the Thunderbird, his supernatural father. (This conflict provided the setting for at least one of the Thunderbird ceremonies performed by the Hidatsa in recent years.)

Before the war party was out of sight, Hungry Wolf threatened that Owns-Many-Dogs dogs would eat High Bird (the narrative at this point describes the penalties to the social group when brothers quarreled. People were quick to put brothers aright if they showed a tendency to quarrel or fight. This applied also to clan brothers. As a result of the destruction of a large part of the population, people learned that brothers must always aid and support each other, revenge the others death by the enemy, and provide for those the brother loved and respected while he lived.)

Thunderbird came down from the sky, learned from High Bird the cause of the quarrel, and gave High Bird advice on escaping from the island. High Bird learned from Thunderbird that the water buffalo was in reality a large snake living in the lake. (Conflict between the sky gods represented by the big birds and the water gods represented by the snakes runs throughout Hidatsa mythology).

High Bird fed the large snake four cornballs to reach shore where the snake was killed by Thunderbird. High Bird cut up the snake and Thunderbird called the other large birds to a feast. (This feast is reenacted by those performing rites to White Fingernails Bundle). These big birds then gave High Bird advice on overcoming the magical powers of Owns-Many-Dogs and the Sharp Noses. Thunderbird decreed that the village where the two young brothers lived would be destroyed unless Hungry Wolf gave High Bird enough tobacco for one pipe filling. Then High Bird started for home.

Northeast of Devils Lake he overcame the Sharp Noses and when he was nearer to Devils Lake he encountered Owns-Many-Dogs and sent her northward beyond the great fire which was to destroy the village. Far to the east, where the rivers flow southward, High Bird heard a man weeping and discovered that it was his friend, the orphan. They reached home and found that a Mourners Camp has been set up, for his relatives had concluded that he was dead. Each day the people from the other camp came there to mimic them by singing victory songs. The Hidatsa and Awaxawi often set up the Mourners Camp. It was not customary for either the Mandan or Awatixa to establish a separate camp of hide tipis as did the other village groups.)

High Bird sent his mother to Hungry Wolf four times for tobacco and each time he refused so the people of the Mourners Camp dug deep holes in which to protect themselves from the celestial flames. Each day the mourners would go to Hungry Wolf’s camp to sing under the direction of seven singers. They sang the Tobacco songs. (Here is the first reference to an institution highly developed with the Crows, who were traditionally a part of the original Hidatsa, and Awaxawi cultures.)

Each day the mourners would go to Hungry Wolf’s camp to sing under the direction of seven singers.

One day a fire came down from the sky. High Bird’s people were in deep cellars and were saved. All of the others were destroyed except Hungry Wolf’s wife who was the cause of the quarrel. She was given the name Calf Woman after the fire. She described the destruction by the fire and it was then decreed that from this time there would always be women who would make trouble between married couples. Because the seven Tobacco singers were with the mourners, the Tobacco rites were saved. Even today one sees the results of this fire, for there are no trees to the east except along the Red River and its tributaries where the fire could not burn.

After this fire the survivors separated, the Awaxawi lived to the south of Devils Lake where they planted corn while the Hidatsa and the Crow with their Tobacco rites stayed farther north near the large lakes. There Magpie discovered an approaching flood, the penalty for sticking a feather through Fat Bird’s nostrils and ordering a buffalo calf to carry its mother’s entrails. Those Awaxawi who believed Magpie escaped to Square Buttes on the Missouri River where they were joined by Magpie, his mother named Yellow Woman who represented corn, and Spring Buffalo. The buffaloes of the other three seasons drowned on the way to establishing three important hunting areas between the Missouri and Devils Lake. (Bears Arm explained that the linguistic differences between the Hidatsa-River Crow and the Awaxawi developed as a result of the separation after the celestial fire. He interpreted this flight from Devils Lake as evidence that the Awaxawi brought gardening to the Missouri and did not adopt the practice from the Mandan. He believed the flight northward to avoid destruction from the flood involved only the Hidatsa and River Crow. We see that the traditional migrations are intimately associated with magical beliefs. (It would appear from the accounts of David Thompson that these migration myths have at least some historic validity.)

…the Awaxawi lived to the south of Devils Lake where they planted corn while the Hidatsa and the Crow with their tobacco rites stayed farther north near the large lakes. – Origin Narrative of the Awaxawi Band

These people who came to the Missouri in advance of the flood were the Awaxawi who had separated sometime before from the Hidatsa and River Crow while still living northeast of Devils Lake; the flood destroyed those who were on lowlands. After the waters had subsided, the Awatixa were found living on the Missouri also. (This is the first reference in this important sacred myth to the Awatixa whose large village at the mouth of Knife River shows evidence of longer occupation than the traditional villages of the Hidatsa and Awaxawi of the same area.)

When the waters subsided, there were lakes and sloughs to the northeast where First Creator and Lone Man had roughened the earth with their heels. Fish became abundant in all of the lakes. (Bowers, pp. 298–301, 1963, appendix C)

Some of the creation stories say that Devils Lake in northern Dakota is the birth lake of the tribe. The Hidatsa call it Mirí-zubáa (pronounced Midihopa) which means sacred water.

In addition to this story, the Hidatsa have an extensive account of what happened to them during their long wanderings on the prairie, from the time they left the lake until they reached the Mandan village. This account is included in a separate story—the almost endless legend of Idawaabísha (pronounced Idi-wabi-sha), when told properly, takes three or four long winter evenings.

In this story they were often on the verge of death by starvation, but were rescued by a miraculous supply of buffalo meat. Stones were scattered on the prairie by a divine order, and from them sprang to life the buffalo, which they slaughtered. It was during these years of wandering that the spirit of the sun took a woman of this tribe up into the sky. She had a son, who came to Earth under the name of idi-wabi-sha, meaning grandchild, and became the great prophet of his mother’s people. (Bowers)

Hidatsa Lifeways

The Hidatsa revered everything in nature. The sun, moon, stars, all animals, trees, plants, rivers, lakes—everything not made by human hands, which has an independent being, or which could be individualized, possessed a spirit, or….shade. (Matthews, 1877, p.48)

To clarify the Hidatsa concept, for example, the shade of the cottonwood, the greatest tree of the Upper Missouri Valley, is supposed to possess an intelligence that may, if properly approached, help in certain undertakings. The shades of shrubs and grasses are of little importance. It was considered wrong to cut down one of these great trees. When large logs were needed, only the fallen ones were used. Some elders say many of the misfortunes of the people are the result of their disregard for the rights of the cottonwood. The sun is held in great respect and many valuable sacrifices are made to it. (Matthews, 1877, p.48)

The Hidatsa women planted beans, sunflowers, squash, pumpkin, tobacco, and corn. The Hidatsa had nine distinct varieties of corn, five varieties of beans, and several varieties of squash.

Child Rearing Practices

Discipline of children was a family responsibility. The mother’s brother was the boy’s chief teacher and disciplinarian. He was likely to chide a boy for failing to learn to do the things that were expected of a boy his age. Old men of the lodge taught boys by stories and lectures instilling in them the tribe’s idea of manhood. Girls were instructed in feminine labors and skills by their mothers and grandmothers. Young women were disciplined by their sisters and by their mothers’ older sisters.

When a husband died leaving children, his brother would be likely to marry the widow to provide for the children. Death, divorce, and other factors created many kinds of marital situations. There were society standards that governed marital behavior. If one acted otherwise he or she was subject to ridicule, and this was enough to maintain the societies’ standards.

Polygamy occurred among all the tribes in this area. The main reason for this practice was the fact that men, constantly engaging in warfare, were more likely to meet early death than were women. In order that all women be provided with the products of the hunt, have opportunity to bear children, and have their share of work to do, the natural solution was plural marriages. When the fur trade was established, it was to the man’s advantage to have several wives to dress skins that could be traded for white man’s goods.

Clans/Moieties

History indicates that there were two different clan systems of the Hidatsa: the thirteen-clan system of the Awatixa and the seven-clan system of the Awaxawi and Hidatsa Proper. The clan was an important feature of Hidatsa social, economic, and ceremonial life. At birth, the child is a member of his/her mother’s clan or, if the mother was without a clan because she belonged to a different tribe, the child assumed the clan of the other children in the household. In spite of the traditional late arrival of the Hidatsa Proper and the Awaxawi on the Missouri River, the clan names they used were based on incidents or events occurring along the Missouri River.

The general idea of clan origins are two: the origin of the clan from a single female of a household group coming down from the sky with Charred Body; and a local group accustomed to living together. The clan names refer to incidents involving people, animals, or objects. The MaxU’xati (Alkalai Lodge) Clan receives its name from maxoxi, which refers to the dry dust that formed from the decaying of the earthlodge rafters and dropped down continuously, and ati meaning “lodge.” The ME’tsiroku (Flint Knife) Clan means “knife people” and refers to an instance of wife-purchase with a stone knife. The Apukaw’I’u (Low Cap) Clan receives its name from apuka meaning cap or article of clothing worn above the eye to shade them from the sun and wiku meaning “low.” The Low Cap Clan was derived from the supernatural experiences of Packs Antelope with the Thunderbirds and the Grandfather snake of the Missouri who killed by means of lightening which flashed from his eyes. When he returned from his exploits with the supernatural, he shaded his eyes to protect the people. These three clans are grouped together and are known today as the Three-Clan Moiety.

The Itisúku (Wide Ridge) Clan received its name from the custom of being out to the front of the war party along the edges of the hills overlooking the Missouri River. Once a group of young men called on Old-Woman-Who-Never-Dies at her lodge near the Red Buttes and she promised them success in warfare. When they returned to their homes, they called themselves Itis’ku.

The Prairie Chicken Clan was believed to have once been a separate village group. The name was derived from the fact that members of this group were noisy like the prairie chickens. The Prairie Chicken Clan began from the custom of a war party to camp at night in the bushes, the berries of which were eaten by the prairie chickens. (Bowers pg. 66–67)

The AwaxEnawita (Dripping Dirt) Clan derives its name from the childhood custom of building tiny villages with wet clay. Later the people saw hills upstream and nearly opposite the present city of Williston, North Dakota, that reminded them of the work of small children. The people camped there three times; hence the name AwaxEnawita taken from awaxE meaning “hill sliding down” and nawi meaning “three.”

The Mirip’ti (Waterbuster) Clan derives its name from a quarrel that occurred in the village. The mirip’ti separated and built near the village of Xura, who, at that time, had a separate village. Water was brought from the river and stored in bladders for use in case of a prolonged attack. One man became angered because of the cowardice of his people and cut up the water bag hanging in his lodge; after this the group was known as Mirip’ ti from Miri meaning “water” and pati meaning “to break open.” The Xura Clan, after the smallpox epidemic of 1837, merged with the Waterbuster Clan and became extinct. The Xura Clan functioned as a named lineage in the Waterbuster or Mirip’ti Clan, is believed to have been a separate village at one time. The name is derived from the noise of the cicada. The village, except for one woman and her baby daughter, disappeared mysteriously during the night. The survivors moved to the village of the Waterbuster of Awatixa and formed a friendship with that group. (Bowers, 1950)

In addition to the eight clans, there were a few members of the Speckled Eagle Clan in the tribe. According to tradition, this clan was of Mandan origin although many members can no longer trace their lineage back to any particular Mandan village group. They lived at the Awaxawi village shortly after 1780 at the time of the smallpox epidemic of Nuptadi village. Like the Mandan Speckled Eagle Clan, they have been assimilating with the Prairie Chicken Clan in recent years and marriage with the Prairie Chicken Clan was generally disapproved.

The clan was responsible for the care of its own members. Old people and orphans were cared for and often taken into the households of clan members. When the wife died, the man generally left the household to live in one where the females were of his clan.

The clan was responsible for the behavior of its members. It was the duty of older persons of the clan to instruct and supervise the children as they grew up. It was the duty of the clan not only to discipline its own members but also to protect them from the attacks of others. An important role was in directing and supervising the fasting of its younger members, and encouraging their participation in all ceremonies.

The clan revenged the murder of a member by killing the offender and demanding goods of his clansmen to make up for the loss. Women of the clan who were ill and could not do the work were assisted in caring for their households and gardens. One might even be brought into the lodge of clanswomen and nursed back to health. Goods and horses were contributed when a clansman performed a ceremony.

Burial Customs

At death, both the person’s own and the father’s clan had important duties. It is the duty of the members of the father’s clan to take care of, or handle, all of the funeral arrangements. The members of the father’s clan who officiated were selected in advance, sometimes years beforehand. It was the duty of the clan to provide goods, horses, and food for the funeral rites as payment for the official mourners who comprised the adults of the father’s clan. The clan members would begin bringing in the property and displaying it on lines within the lodge where those caring for the sick person and friends coming in for a last visit would see them. It was believed that a lavish display of goods expressed the generosity and solidarity of the clan. The sick person was happy in the belief that in the spirit world he could boast of the goods that had been given away when he died. The clan had no other role when death of a member occurred. Individuals of the father’s clan were in charge of the last rites.

Other duties of the father’s clan included naming ceremonies. Informal feasts were given to the people of the father’s clan from time to time. All through life, the people of the father’s clan offered prayers and sold sacred objects and rites to the clan children, “sons” and “daughters,” and in death they sent the spirit of their clan children away with appropriate rites.

The clan played an important part in uniting households and integrating the village population. It brought together many households for common purposes. It also united households with those of other villages. Visitors from surrounding villages were housed with clansmen, and assisted and participated in the ceremonial activities. A common clans system played an important role in holding the tribal population together and avoiding inter-village warfare.

Kinship System

Kinship plays an important part in the lives of the Hidatsa people. Relatives address each other by the term of relationship instead of by proper names, and each person’s behavior and attitude towards his relatives depended upon the kind of kinship. The requirements for special usage extended beyond blood relationship into larger groups such as clans and moieties. The many loyalties, obligations, and associations of the individual were determined at birth.

Tribal custom laid down certain rules for attitude and behavior toward people of each degree of relationship. Hidatsa kinship influenced behavior of individuals toward each other. For example, a boy could be disciplined by his elder brother and by his mother’s brother. A man could have no conversation with either of his in-laws, or certain of their relatives, but brother-in-law were intimate friends, often exchanging gifts. A man and his sister had great respect and affection for each other, but after puberty they rarely spoke to each other. People whose fathers were of the same clan were expected to chide each other about any weaknesses or breach of a custom.

Among the Mandan and Hidatsa the ideal lodge would include an elderly man and his wives, their unmarried sons and daughters, and the married daughters with their husbands and children. When a lodge became crowded, one of the daughters would build her own lodge and move there with husband and children. The lodge was the property of the women who lived in it. They also owned the household furniture, the tipi, the corn scaffolds, cache pits, dogs, and gardening equipment.

Societies of the Hidatsa and the Mandan

The purpose of societies was mainly to provide opportunity for visiting, feasting, and dancing with a group of people of the same sex. The distinctive features of each society were characterized by a series of songs and a dance, peculiar forms of rattles and other instruments, certain articles of dress and adornment, a specified face and body painting, and hair dress. Society traits were borrowed freely from tribe to tribe and functions were purchased. Though not primarily concerned with the supernatural, a few societies contained sacred elements; most evident is the buffalo-calling dance of the White Buffalo Cow Society of the Mandan and Hidatsa.

Mandan and Hidatsa societies were graded according to age of members. The members of any one society tended to be about the same age. When they became older, they sold their membership in that society and bought membership in the next higher society. Most societies had a leader, and a set number of singers, waiters, and pipe-bearers. In several cases, the acceptance of an emblem, such as a special kind of lance, obligated the owner to behave in a certain way in battle. Two officers in the Hidatsa Black Mouth Society carried “raven lances” into battle. If one was pursued by the enemy, he was to plant the lance in the ground and fight beside it until killed, or until a fellow tribesman pulled up the lance.

There was a society especially for pre-adolescent boys to hunt as soon as they were able. Boys began fasting at the age of nine.

Since kinship ties were strong in these cultures, any adult had responsibilities far beyond the ties of his household. Both men and women had duties to perform for their relatives in matters of marriage, burial, society entry, bundle feasts, and religious rites. Ceremony took up a good deal of the time of the adult Mandan and Hidatsa.

Crafts

The Mandan and Hidatsa were making pottery as far back as their villages can be traced by archaeology, and continued to do so up to the time of the 1837 epidemic. The art was declining because of the introduction of more durable metal pots and pails by traders.

They used paint to decorate robes, tipi covers, rawhide packing cases, scabbards, shields, drums, and shirts. The usual tint was earth colored and some vegetable colors. Commercial paints became available through traders by the 1800s. The designs were of two styles—the men usually had life forms and women used geometric designs. Men often painted their war exploits and figures of horses. Their paintings were dominated by fighting men. They often painted symbols of their bundle rights on their robes.

Baskets were made of the inner bark of willow and of box elder on a frame of willow sticks. Three colors were available—a reddish brown, blacks, or white—the basic colors of the willows and the box elder. These baskets were used for carrying corn and other plant products, and often used as a measure of commerce.

Articles of clothing were made of tanned deer and elk skin and were often decorated with colored quills and later beads. The porcupine quills were usually dyed with vegetable dyes at first then aniline dyes brought by traders.

Men painted and made their own weapons, society regalia, musical instruments, and ceremonial equipment. In primitive times they made projectile points, knives, and drills from stone. A few individuals had learned to melt glass, using the blue beads brought by the traders, and pour it into clay forms to make plain, but highly prized, pendants.

Games

Certain games were restricted to men, women, and children—other games were not. When adults played games they were likely to bet heavily; gambling on games of chance, guessing, and skill was noted by most travelers who went among the tribes. Gambling was an annoyance to missionaries and government agents. Most games were played only at fixed seasons. This was because of weather conditions or the mythical associations of the games.

Dwellings