Introduction

The People's Name

The Chippewa proudly referred to themselves as Anishinabe meaning “The Original People.” The Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa is primarily members of the Pembina Band of Chippewa. Descendence may include intermarriage with other Chippewa bands, Cree, and other nations who make up the membership of the Turtle Mountain Band.

The name Chippewa, a mispronunciation of Ojibwa, Ojibway, Ojibwe, Saulteaux, and Anishinabe are all names that refer to the same group of people. The word “Ojibwa” refers to “something puckered up.” One theory is that it comes from the way in which the people made their moccasins. For the purpose of this discussion, the term “Ojibway” is used when referring to the tribe’s early history. The term “Chippewa” is used after European contact.

The Ojibway are members of the Algonquin language group which are located from Newfoundland to the Rocky Mountains and from Hudson Bay to North Carolina. Other tribes in this language group are the Cree, Ottawa, Sauk, Fox, Menominee, Potawatomi, Miami, Shawnee, Delaware, Cheyenne, Blackfeet, and the Arapaho. This classification by language has been established by scholars, but this does not mean that the tribes are closely related or that they were allies.

Ojibway Creation Story

The Ojibway of this continent have their own creation story. The following creation story has been recorded on birch bark scrolls and passed down orally through generations. The Ojibway believe they have always lived in North America. It was during the winter season that elders recounted tribal stories and events. The Ojibway describe their beginning in the following creation story.

When Ah-ki’ (the Earth) was young, it was said that the Earth had a family. Nee-ba-gee’sis (the moon) is called Grandmother, and Gee’-sis (the Sun) is called Grandfather. The Creator of this family is Kitchie Man-i-to’ (Great Mystery or Creator). The Earth is said to be a woman. In this way it is understood that a woman preceded man on Earth.

Long ago, Kitchi Manitou had a dream. He saw the sky filled with the sun, earth, moon and stars. He saw the earth covered with mountains and valleys, lakes and islands, prairies and forests. He saw trees, flowers, grass and fruit. He saw all manner of beings walking, flying, crawling and swimming. He saw birth, growth, and death. And he saw some things that lived forever. Kitchi Manitou heard songs and stories, he touched wind and rain, and he experienced every emotion.

After his dream, Kitchi Manitou made rock, water, fire, and wind. Into each he breathed life and to each he gave a different essence and nature. From these four elements Kitchi Manitou created the stars, sun, moon, and earth. Kitchi Manitou gave special powers to all of his creations. To the sun he gave the power of light and heat. To the earth he gave growth and healing. To the water he gave the power to purify and renew. And to the wind, he gave the voice of music and the breath of life.

On the new earth, Kitchi Manitou made mountains, valleys, plains, lakes, islands, and rivers. Everything had its place on the new earth. Next, Kitchi Manitou sent his singers in the form of birds to the Earth to carry the seeds of life to all of the Four Directions. [He organized the world by the Four Directions: Wauban (east), Shawan (south), Ningabian (west), and Keewatin (north). Two other sacred directions were the Sky above and the Earth Below. (Tanner 1992) In this way life was spread across the earth. The Creator made the plants. There were four kinds: flowers, grass, trees, and vegetables. To each plant he gave the spirit of life, growth, healing, and beauty. And he placed each one where it would be most beneficial. Kitchi Manitou then created the animals and gave each of them special powers. All of these parts of life lived in harmony with each other...

...Kitchi Manitou then took four parts of Mother Earth and blew into them using a Sacred Shell from the union of the Four Sacred Elements and his breath, man was created.

It is said that Kitchi Manitou then lowered man to the Earth. Thus, man was the last form of life to be placed on the Earth. From this Original Man came the A-nish-i-na’-be people. In the Ojibway language if you break down the word Anishinabe, this is what it means:

ANI NISHINA ABE from whence lowered the male of the species Kitchi Manitou created us in his image. We are natural people. We are a part of the Mother Earth. We live in brotherhood with all that is around us. Although last and weakest of his creations, we were given the greatest gift of all, the power to dream. Thus, Kitchi Manitou has brought his dream to life. (Benton-Benai, 1979)

Man, as the last of Kitchi Manitou’s creation, regarded plants, animals, and all of creation as elders because those life forms were created first.

The Great Flood

Stories were always a way of teaching. The following legend refers to the Ojibway’s oral legend of the great flood.

Sky Woman looked down upon the waters that covered the earth after the great melting of the ice. She saw a Giant Turtle (who was called Mekinok) in the water and came down to stand upon his strong back. Then, she summoned Muskrat whom we all know as a strong, determined swimmer. Sky Woman told Muskrat to dive down into the water as far as he could—to find a part of the earth. Three times he dived, but came up empty. The fourth time, Muskrat was gone a very long time. Sky Woman grew weary, but She waited patiently and prayed. Finally, she saw a gleam of bubbles far down in the depths. Soon, Muskrat broke the surface of the water gasping for breath, but he had a piece of mud in his paws. Sky Woman thanked Muskrat and told him that he would always have a home on the land and in the water as well. She then took the wet dirt into the palm of her hand, dried it and blew gently, to the north, to the east, the south and the west. Wherever the dust from the dirt went, land came up around the Giant Turtle. Soon the land completely encircled Mekinok. And Mekinok became Turtle Island, the center of the world and the birthplace of the Anishinabaug, the original people. As the land grew, even Mekinok became covered with top soil and the Anishinabaug called him Mekinok Wajiw (the mound of earth that is a turtle). Today, it is called Turtle Mountain. (Turtle Mountain Community College Self-Study, 1993)

The Birth of Nanabozoho

Many tribes have stories which include a “spirit or trickster” character. This character’s role was to explain and teach lessons of value. Nanabozoho is a spirit character of Ojibway legends.

An elderly woman lived with her daughter in a small home in the woodland country. The old woman warned her daughter not to sit facing the West. One day when the sun was warm and shining bright, her daughter forgot her mother’s warning and went outside and sat facing West. Suddenly she felt the cool west breeze chill her body. She ran to tell her mother what had happened. “You should have listened to me,” said her mother. Soon, the daughter became ill. Before she died, she dripped blood onto a piece of bark that was in the room. The old lady put her daughter to rest and placed the bark aside. One day she looked at the bark and found that the drop of blood on the bark had begun to grow. She watched it grow until it grew into a baby. “What is happening?” she asked. “O Nokomis! Do you know me?” asked the baby. “I am your grandson, Nanabosho.” (Johnston, 1979)

Migration

The Ojibway moved from the Great Salt Lake in the east to their westward locations in the center of America. William Warren (1885) told about the migration by sharing a story that was told during a ceremony he attended. According to Warren, the spiritual leader held a Me-da-wa-me-gis, a small white shell, in his hand as he related the following:

While our forefathers were living on the great salt water toward the rising sun, the great Megis (Sea Shell) showed itself above the surface of the great water, and the rays of the sun for some long periods were reflected from its glossy back. It gave warmth and light to the An-ish-in-aub-ag (red race).

All at once it sank into the deep, and for a time our ancestors were not blessed with its light. It rose to the surface and appeared again on the great river which drains the waters of the Great lakes, and again for a long time it gave life to our forefathers, and reflected back the rays of the sun. Again it disappeared from sight and it rose not, till it appeared to the eyes of the An-ish-in-au-baug on the shores of the first great lake. Again it sank from sight, the death daily visited the wigwams of our forefathers, till it shown its back, and reflected the rays of the sun once more at Bow-e-ting (Sault Ste. Marie). Here it remained for a long time, and once more, and for the last time, it disappeared, and the An-sih-in-aub-ag was left in the darkness and misery, till it floated and once more showed its bright back at Mo-nig-wun-a-kuan-ing (La Pointe Island), where it has ever since reflected back the rays of the sun, and blessed our ancestors with life, light, and wisdom. Its rays reach the remotest village of the wide spread Ojibways. (Warren, 1885, 1984)

The spiritual leader explained the story to Warren (1885):

The “Megis” he spoke of referred to the Me-da-we religion. According to the leader, each time the Me-da-we lodge was erected it was indicated as the “Megis” in the story. The final lodge [in this narrative] was erected on the Island of LaPointe. This is where the Me-da-we-win was practiced in its purest form. It remained so until the Europeans appeared among them. It is from this site that all of the Ojibway tribe first grew, and like a tree it has spread its branches in every direction, in the bands that now occupy the vast extent of the Ojibway earth.

The Ojibway migrated in many directions. They lived on the eastern shores of Turtle Island (North America) around 900 A.D. and eventually established their aboriginal territory in the woodlands of Canada, Michigan, Minnesota, Wisconsin, and eventually North Dakota and Montana. Around the beginning of the 17th Century or shortly thereafter, the Ojibway moved westward to the shore of Lake Superior. This migration was taking place on both the north and south shores of Lake Superior. The tribes that were to the north of the lake were mainly Ojibway and Cree with whom they shared familial ties. The Ojibways to the south of the lake were called “Chippewa”—an English mispronunciation of Ojibway.

Contact

The shores of Lake Superior were vastly populated by the Ojibway when the Jesuits and French traders recorded contact in 1640. An Ojibway chief by the name of Copway stated first contact with Champlain traders occurred as early as 1610. Ongoing contact with the French missionaries and French traders during the 17th and 18th centuries had an enormous impact on the lifestyle of the Ojibway. Early settlement brought them in proximity to the Assiniboine and Cree, and in conflict with the Dakota over territory, as they moved into the location that is present-day northern Minnesota.

Very early the Ojibway were involved in trade, first among other Ojibway bands, and later with the fur traders. The tools that the French traded consisted of such things as steel knives and copper kettles. The efficient tools of the French were easily adapted by the Ojibway. The previously used stone and bone utensils became necessary items.

The acceptance of the French fur trader had a social and psychological impact on the culture of the Ojibway. The Ojibway had always hunted and trapped for survival. They also traded among other tribes before Europeans. Originally, the Ojibway were middlemen for the Mandan, Hidatsa, and other tribes who bartered with the fur traders. As resources became scarce, the Ojibway were forced to adopt trading furs for goods to survive. The fur trade deepened the relationships between the Ojibway and Cree, and French traders, resulting in marriages between them. These associations were based on a sharing of economic, social, and physical resources. The first generations of offspring of these marriages were raised as their mothers’ people. In time, some of the children of the Frenchmen and their Ojibway and Cree wives became known as “Métis” or “Metchif.” Contact between the French, the Europeans, and their Woodland relatives brought about many alliances during the fur trade era. These people retained many of their tribal customs.

Chippewa Influence and Involvement in the Fur Trade

As the fur trade flourished in the first half of the 17th century, the Ojibway played a central role in its development. In 1670, the English Hudson Bay Company set up posts and obtained furs directly from the Indians who had an established trade system in the Great Lakes region. The English were in competition with the French fur trade companies, who had trapped and traded with the Indians from as early as 1610. This competition was over the Indian trade in the Hudson Bay and the Great Lakes and their tributaries. A “head on” confrontation between these two countries was fueled by a swiftly diminishing supply of furs, resulting in a conflict known as the French and Indian War.

Pierre Bottineau Pierre Bottineau was an early trader among the Turtle Mountain Chippewa. (Photo courtesy of the State Historical Society of North Dakota, 1850-1860)

In 1763, the English gained control of the fur trade both in Canada and the Great Lakes area. As the Hudson Bay Company assumed many of the older French trading posts, new settlements came into existence. Grand Portage (the great carrying place), a well known trading center, came into existence.

All trading goods going east or west had to be portaged (carried) over rugged steep trails from Lake Superior to reach the chain of lakes along the northern border of Minnesota. In the summer, traders and Indians all gathered at Grand Portage to barter their goods. In order to withstand the rigors of portaging goods over land and along the waterways, a group of skilled oarsmen evolved, known as the “voyageurs.” The voyageurs were French Canadian, Cree, and Ojibway canoe men who became a critical link in the success of the North American fur trade. The voyageurs portaged through the wilderness of rivers, lakes, and seaways in the Northwest Territory. Their appearance was colorful. They wore bright red caps, hooded cloaks, braided sashes, and beaded pouches. Their leggings and moccasins were made of deer hides. They were known as cheerful men capable of great endurance and physical strength.

Pembina Post Established

The Red River became an arterial of travel for the trappers at the end of the 18th century. Trapping was done along the Assiniboine and Red Rivers and all their tributaries. The establishment of trading posts transformed the Red River into a commercial trade economy, to which many Chippewas were accustomed.

The Chippewa occupied the territory of northern Minnesota, from Red Lake, Leech Lake, Sandy Lake, Lake of the Woods and Rainy Lake to Lake Superior and Lake Winnipeg Traverse. The regions around these lakes became their more permanent settlements. During the hunting/trapping season, the men canoed the Red and Assiniboine Rivers and a vast number of tributaries. The numerous trading posts along the Red River assisted in the growth of fur trade and westward movement.

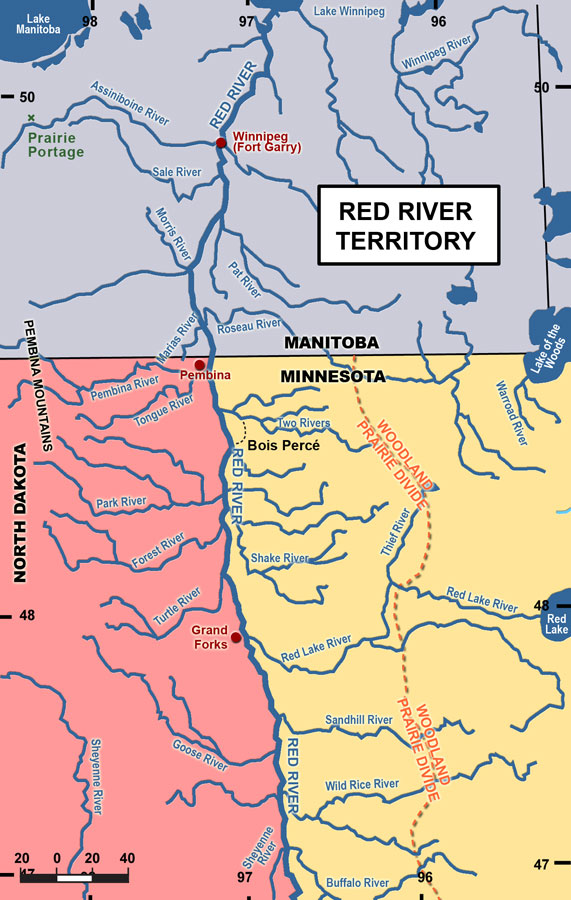

Red River Territory The map shows the Red River area during the Pembina fur trade era, around 1800. (Map by Cassie Theurer, adapted from Ethnohistory, 1959, page 300)

During the Pembina fur trade era, the Red River Territory was overly abundant with furred animals. In 1797, the Northwest Fur Company, from Montreal, established a major trading post where the Red and Pembina Rivers join. This was the first post at Pembina. Peter Grant was the first proprietor, and Charles Jean Baptist Chaboillez of the North West Company was the second. Chaboillez operated his post from 1797 through 1798 where he had dealings with about 80 Chippewas from the Red, Rainy, Leech, and Sandy Lakes area. Chaboillez’s post was one of three established along the Red River. The second post was located at the mouth of the Red River and was operated by the Hudson Bay Company. The North West Company set a post at the junction of the Forest (Salt) and Red Rivers. (Hickerson 1956, p. 303)

A second post at Pembina was opened three years later by a man named Alexander Henry. He operated the post at this site from 1801–1805, and recorded his dealings. He also set up many sub-posts along the Red River, depending on the supply of furs in each area. The post was the focal point of trade in the middle Red River region. Pembina became the chief North West Company trading post along the Red and Assiniboine Rivers. The number of Chippewas who traded in the area increased each year, but the supply of fur was rapidly diminishing.

Move to the Plains, 1790–1820

The transition of the Chippewa from the woodlands to the plains occurred near the end of the 18th century. French and English fur traders had traveled with the Chippewa as far as the Turtle Mountains. Having acquired guns and ammunition from the traders, and horses from the Mandan and Hidatsa, the Chippewa had an advantage in obtaining territory in Dakota. They had spent a decade utilizing the rivers of the Red River Territory. However, by 1807 this region was virtually depleted of wild game and furred animals. Feeling the hard times, these bands returned to their woodland homes in Minnesota. One group, the Mikinak-wastsha-anishinabe, a band of Chippewa, left the Pembina settlement and established themselves in the Turtle Mountains.

The Pembina Band of Chippewa advanced westward for several reasons. First they had acquired the horse and developed the Red River Cart. Alexander Henry (Younger) stated in his Journals that one cart was as useful as five horses. The Turtle Mountains were plentiful in resources. Abundant in muskrat, beaver, fish, deer, and buffalo, the Turtle Mountains allowed the Chippewa to maintain a thriving fur trade. This region was filled with lakes and water resources as well as several types of medicinal and edible plants. At the same time, the Turtle Mountains offered a refuge from the encroachment of white settlers. Although they moved to the plains, the Chippewa still traded at the posts in Pembina, as well as trading with the Mandans and other tribes at Fort Union.

Pembina Settlement

Today, we know Pembina to be a small rural town in northeastern North Dakota. However, the region known as Pembina, and described by Father Belcourt in 1849, consisted of a much larger land base. The priest explains the boundaries of Pembina in a letter to Major Woods (who was in charge of the Red River Expedition in 1849):

We understand here, that the district or department called Pembina, comprises all of the country or basin which is irrigated or traversed by the tributaries of the Red River, south of the line of the 49th parallel of latitude. The prairie, rivers, and lakes which extend to the height of land of the Mississippi, and the immense plains which feed innumerable herds of bison to the westward and from which the Chippewa and half breeds of this region obtain their subsistence, contains within their limits a country about 400 miles from north to south and more than five hundred miles from east to west. (Executive Document 51, pg. 37)

The ox-drawn Red River Cart was first introduced to the plains from Pembina around 1805. Within a few decades there were great trains of these carts, carrying buffalo hides and other trade goods to St. Paul, Minnesota and Winnipeg, Canada. These famous carts were also widely used on buffalo hunts. Red River Carts gave the Chippewa and their Assiniboine and Cree allies a method of transporting huge amounts of pemmican and hides for trade, and hunting in massive groups.

Concerns in Pembina Territory

The Chippewa first established themselves at Pembina in the early 1800s. They had in their company a resident Canadian priest. They built a church and many marriages and baptisms were recorded at this mission site. In 1849, this priest, Father Belcourt, through correspondence, interceded on behalf of the people. He informed Major Woods of the trade dealings of Hudson Bay Company. Although it was forbidden to trade alcohol, Father George A. Belcourt was aware that during the previous year, one-fifth of all imports from the Hudson Bay Company consisted of rum.

In addition, the smallpox epidemic had wiped out camps of Chippewa, leaving as few as one in ten alive. Father Belcourt wrote:

The small pox, not very long since, found its way among them and not only decimated, but in many of their camps did not leave one in ten alive. Here on the banks of the Pembina there is not a spot near the river where the plough share does not throw out of the furrow quantities of human bones, remains of the destructive scourge.(Executive Document 51, p. 37)

The priest categorized the people. Taking the posts of Red Lake, Reed Lake, Pembina, and Turtle Mountain into consideration, the priest believed there was a total of 2,400 Chippewas. He went on to comment that the Métis (French word meaning mixed-blood) were greater in numbers than the Chippewa. The priest believed there were more than 5,000 Métis in the Pembina Territory.

Included in his letter to Major Wood, Father Belcourt suggested that possibly the United States government could be the middleman for a treaty between the Chippewa and Dakota. He suggested the government declare imprisonment or other punishment for Indians committing hostilities against each other.

Conflict with the Dakota

In addition to bringing food and furs to the Chippewa, the Red River also brought danger. The encroachment of white settlers to the east, and the westward movement of the fur trade, brought them closer and closer to their territorial rivals, the Dakota. The Chippewa camped in forests to the east of the Red River in order to avoid confrontation with the Dakota, who held claim to the land along the Red River. With the acquisition of the horse, the Dakota had a big advantage over the Chippewa. Without horses the Chippewas were almost always out-maneuvered. In 1798 a Chippewa Chief of Red Lake, named Sheshepaskut, expressed his view on the advantage of the Dakota:

While they keep to the Plains with their horse, we are not a match for them; for we being foot men, they could go windward of us and set fire to the grass; when we marched for the woods, they would be there before us, dismount, and under cover fire on us. Until we have horses like them, we must keep to the woods and leave the plains to them. (Hickerson, 1956)

The Chippewa and Dakota had long been doing battle over territory. The Red River was almost a natural boundary line dividing the woodlands from the plains. Battles over this territory, where both sides received heavy losses, continued until the 1858 Sweet Corn Treaty, some 50 years later. (Hickerson, p. 296)

Treaties

The history of treaty-making began with European countries, mainly Great Britain. The premise for making treaties had established precedence in 200 years of British law in America. These laws recognized aboriginal title (original ownership) and the inherent rights attached to it. When the first colonists arrived in Massachusetts and Virginia, they were in desperate need of necessities including land to build their homes and communities. In order to obtain land, they made formal and informal agreements with the Indian tribes who occupied the land. This process was acknowledged and encouraged when the United States formed. The colonists, and then the government, adopted the practice of negotiating formal treaties with Indian tribes. In doing so, they upheld inherent rights attendant to ownership in land. In a series of proclamations and ordinances codified during 1783, 1786, and 1787, the Continental Congress defined the central role between Indian nations and the central government. The 1787 Northwest Ordinance held that:

The utmost good faith shall always be observed toward the Indians; their lands and property shall never be taken from them without their consent; and, in their property, rights, and liberty, they shall never be invaded or disturbed, unless in just and lawful wars authorized by Congress; but laws founded in justice and humanity shall from time to time be made for preventing wrong being done to them, and for preserving peace and friendship with them.(Utter, 1993, p. 245)

The United States Constitution, ratified in 1789, confirmed the federal role in Indian policy by assigning Congress the authority to involve itself in Indian Affairs. The Commerce Clause (Article I, section 2, clause 3) and the Treaty Clause (Article II, section 2, clause 2) of the United States Constitution granted authority to the United States government to enter into treaties with Indian tribes. The first treaty made with the United States was with the Delawares in 1778. After that time, 370 treaties were entered into between American Indian tribes and the United States. Through the treaty process the United States acquired lands and legal [trust] responsibilities. (Pevar, 1995, p. 37) The tribes ceded lands and obtained federal commitments for annuities, provisions for education, and other forms of compensation in return. (Utter, 1993, p. 246)

Sweet Corn Treaty

In 1858, with the assistance of the U.S. government, the Chippewa and Dakota defined their boundaries within the Sweet Corn Treaty. The land defined as Chippewa land is described as:

Commencing at the mouth of the river Wahtab, thence ascending its course and running through Lake Wahtab: from thence taking a westerly course and passing through the fork of the Sauk River: thence running in a northerly direction through Otter Tail Lake and striking the Red River at the mouth of Buffalo River: thence following the course of the Red River down to the mouth of Goose River: thence ascending the course of Goose River up to its source: after leaving the Lake, continuing its western course to Maison au Chine: from thence taking a northwesterly direction to its terminus at a point on the Missouri River within gunshot sound of Little River.

In the treaty between the Chippewa and Dakota, they agreed to abide by the boundaries, as well as allowing each other, in a neighborly manner, to hunt on each others land if game was scarce on either side. They also agreed that depredations by members of each tribe, such as stealing horses, needed to be dealt with, either by return of property, or repayment for damages. These articles were agreed upon 33 years earlier by the forefathers of these two tribes, Chief Waanatan (He Who Rushes On) for the Dakota, and Chief Emay das kah (Flat Mouth) for the Chippewa. To bind the treaty, oral history states that there was an exchange of tribal members. “We will not make war against our grandchildren” was a statement made by the treaty signers.

The United States government and settlers wanted to prove that the Chippewa did not hold aboriginal claim to the land that was intended to become their reservation. A Grand Council meeting was held between the Chippewa and Dakota at a point north of the Sheyenne River and west of Devils Lake in July of 1858. Chiefs involved in the signing of this treaty were Mattonwakan, Chief of the Yanktons, and La Terre Qui Purle, Chief of the Sisseton Band. Also signing was a large representation of braves and warriors of the Dakota Tribes. Representing the Chippewa was Chief Wilkie known as Narbexxa who was a well-respected follower of Little Shell.

Based on the documentation from the Sweet Corn Treaty, the Chippewa were able to claim 11 million acres of land that the government wanted for a public domain. The land described in the Sweet Corn Treaty was used later by the government and provided supportive documentation of Chippewa title in the Old Crossing Treaty and even later the McCumber Agreement.

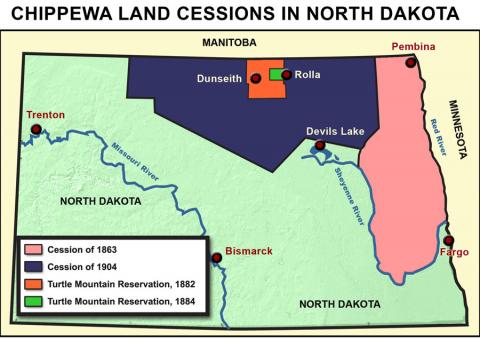

Old Crossing Treaty

By 1863 the Chippewa occupied over one-third of what is now the State of North Dakota, including the Red River Valley. With the American philosophy of manifest destiny and the Homestead Act, settlers petitioned Washington to pressure government officials to make treaties with the Indians who had the rights to the land. The settlers recognized that the Red River Valley was a rich and fertile agricultural area.

On October 2, 1863, at the Old Crossing of the Red Lake River in Minnesota, the Chippewa Chiefs, headmen, and warriors of the Red Lake and Pembina Bands met with Alexander Ramsey and Ashley C. Morrill, Commissioners for the United States government. The purpose of the meeting was to obtain Chippewa land through the treaty process. The Chippewas were represented by the chiefs of Red Lake and Pembina. The Red Lake chiefs were: Monsomo (Moose Dung), Kaw-was-ke-ne-kay (Broken Arm), May-dwa-gum-on-ind (He That is Spoken To), and Leading Feather. The Chiefs of the Pembina Band were Ase-anse (Little Shell II) and Miscomukquah (Red Bear).

The Chippewa signed the treaty under protest. The government attained these 11 million acres of land and opened it up to white settlers. The land extended about 35 miles on either side of the Red River from the Canadian border to near present-day Fargo, North Dakota. The land was acquired at eight cents per acre. Ramsey was said to have stated: “No territorial acquisitions of equal intrinsic value have been made from the Indians at so low a rate per acre.”

Red River Uprising

After the Chippewa ceded the Red River Territory in the 1863 Old Crossing Treaty, the land to the south of the 49th parallel was opened as public domain lands. The Métis to the north of the boundary were being denied their land holdings on ancestral lands by the government of Canada. For more than fifty years, the Canadian Métis had made this northern territory their home. They had developed small river front settlements and began to use the land for agricultural purposes to supplement their livelihood. Prior to this time, many Métis had settled south of the international boundary line. In 1823, when Major Stephen H. Long surveyed the international boundary, he established that Pembina was in United States territory. The Métis had settled in Pembina because of its proximity to the trade routes, and the relationships they had established at the Pembina trading post. The Hudson Bay Company, on the other hand, was within the Canadian boundary. Because the Métis relied on the Hudson Bay Company as their market for trade goods, the Company was able to coerce many Métis traders to move north across the international boundary into Canadian jurisdiction.

In 1865, the Métis were discontent. The Red River Métis were aware their land holdings were in jeopardy. The Canadian government would not listen to their grievances. No longer satisfied, the Métis joined together, under the leadership of Louis Riel, Jr., and rebelled against the Dominion of Canada. Canada was in the process of becoming its own country. The Hudson Bay Company had just surrendered title to these lands. In addition, Canada, at this time, was legally without a government. Riel developed a “Bill of Rights” and he and his supporters formed a provisional government in November of 1869, to represent the Métis. Riel also developed a list of grievances that would benefit Canadian, English, American, and Indian people alike. The document provided for religious, cultural, language, and land rights. Riel, and his supporters, formally declared the establishment of a provisional government in November of 1869, and demanded rights as loyal citizens of the Crown.

The situation got out of control for Riel and his followers. The provisional government took hostile locals as prisoners and one of them was executed. The opposing Canadian officials and the new Governor of Canada, commissioned troops and forced Riel and his armed followers to flee for their lives. Although the “Bill of Rights” Riel developed was implemented by the Canadian government and known as the Manitoba Act, Riel and his supporters were not granted amnesty for their actions. Louis Riel was exiled from the Canada for five years.

1885 Resistance

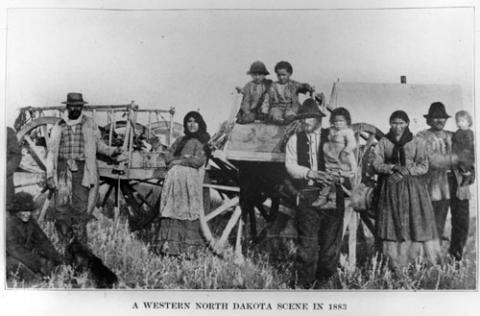

Louis Riel became a United States citizen, married Margaret Monette, and was living in Montana in 1885 when he was approached by a group of Métis from Prince Albert, Canada, requesting his help. Riel again drafted a petition which listed the grievances of settlers and Métis. Again, the petition was ignored. After actual battles with the British, Louis Riel surrendered himself and was brought to trial. This man, who fought so hard for the rights of the Métis, was accused of being a traitor. Riel, a French Métis Catholic, was tried for committing acts of treason against Canada and found guilty by a jury of English Protestants. Riel was hung at Regina, Manitoba, in 1885. With the death of Riel, many of his followers fled to the Turtle Mountains to seek political refuge among relatives. This event created an influx of Métis to the Turtle Mountains. (Howard, 1994, pp.147–194

McCumber Agreement

Throughout the treaty era, the Indian people witnessed the inconsistent behavior of the United States government. They lived and witnessed the false hope of the Great White Father and were left with little or no land, and were poverty stricken. The trust between the Indians and the government had dissipated. The United States, following the civil war, could ill afford to continue treaty-making. As a result, the President established the Grants Peace Commission in 1868, and proposed a policy to make agreements with all of the tribal nations across the country. This policy was to bring about an end to the Indian wars on the plains, and to open the routes west for an ever-growing flood of emigrants. In 1871, Congress revised its policy of “treaty-making” and continued to negotiate, but called the process “agreements” rather than treaties. The era of making treaties was coming to an end.

The first agreement to be made with the Pembina Band of Chippewa was the McCumber Agreement. The Chippewa occupied the east and north central parts of North Dakota, a favorite hunting and wintering ground. The hunting and trapping lifestyle of the Chippewa kept them moving throughout the year. During their absence settlers began to occupy Chippewa lands. There were requests from settlers to remove the Indians from North Dakota. Politicians even refused to credit the Chippewa for their aboriginal title to the lands. The government attempted to move the Turtle Mountain Chippewa to White Earth in Minnesota, but because of the provisions in the Sweet Corn Treaty with the Dakota, the Chippewa claim remained valid.

Some of the people did move to White Earth. Little Shell III and his band stayed in the Turtle Mountains. White settlers, hungry for land, continued to encroach on Chippewa territory in the Turtle Mountains. In July of 1892, Little Shell III and his followers posted signs in the Turtle Mountains stating:

It is here forbidden to any white man to encroach upon this Indian land by settling upon it before a treaty being made with the American government.

Little Shell’s warning caused settlers to petition the government to open lands claimed by the Turtle Mountain Chippewa. By October of 1882, the Secretary of the Interior had opened up lands for settlement without negotiating with the Chippewa. When the government put the lands of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa into the public domain and began to issue homesteads to white settlers, a delegation of tribal members went to Washington. Their task was to petition the government and be recognized to their right to nearly 10 million acres of land in North Dakota.

Chief Little Shell III did not agree with the McCumber Agreement and refused to sign. Because of his refusal to sign, the government would not recognize Chief Little Shell and his Grand Council of 24 as hereditary leaders of the Band. Since they did not recognize Little Shell, U.S. Indian Agent John Waugh handpicked a council of 16 full-bloods and 16 mixed-bloods to meet with the Commissioners. This group has been referred to as the “Council of 32.” This process was all done while Little Shell was in Montana. During the absence of Little Shell, the second Chief, Red Thunder, presided over the 24 member council meeting. In this meeting they agreed to enlist John B. Bottineau as their attorney. They also decided that all the mixed-blood descendants were members of the band, an action that was agreed to by the more than 300 members present. In 1892, Red Thunder addressed the McCumber Commission:

When you (white men) first put your foot upon this land of ours, you found no one but the red man and the Indian woman by whom you have begotten a large family. Pointing to the half-breeds present, he said: “Those are the children and descendants of that woman, they must be recognized as members of this tribe.” (Executive Orders of 1882 and 1884)

One of the provisions of the McCumber Agreement required a census to be taken. McCumber’s agent reported small numbers (about 25 full-blood families) were living in the Turtle Mountain areas. Because of the way the rolls were taken, many were not fairly represented. Little Shell and his followers were excluded from the rolls, leaving a total of 520 people stricken from the rolls. Little Shell and Red Thunder protested this action. Many of the people who were removed from the roll moved to Montana.

Little Shell Protest, 1892

In the early 1880s, there was severe drought and several brutal winters. Many people starved. The McCumber Commission of September 21, 1892, was attended by P.J. McCumber, John Wilson, and W. W. Flemming at the Turtle Mountain Indian Agency. They met with Agent Waugh and his “handpicked committee of 32,” who had not been agreed upon or recognized by the Turtle Mountain Band. The purpose of the meeting was to negotiate with the Turtle Mountain people on the cession and relinquishment of lands claimed by them, and to determine the number entitled to be listed on the rolls. (Act of Congress, Chapter 164, p. 139, 52nd Congress, 1st Session)

The meetings were held at the agency storehouse, which was inadequate in size. After Agent Waugh and his group were inside only enough room was left for about one-fourth of the tribe to be present. Those that were present were obstructed by partitions and supplies. As a result, the proceedings were difficult to hear or understand.

Upon their arrival at the meeting, Little Shell and his council were informed they were not invited and their people would not be fed. Waugh apologized to the commission saying that the Indians misunderstood his letter to them. However, his letter, in fact, stated the commission would be at the agency to meet with them. Little Shell and his followers were turned away, and told that if they had anything to do, they had better do it. Little Shell left the meeting.

John B. Bottineau, attorney for the Turtle Mountain Band, reported to Little Shell the action of the Commission regarding enrollment. The commission turned away many members of the band who were starving. Many desolate, starving people returned home. In spite of their pitiful condition, they took a collection amongst themselves to allow Little Shell and his council to represent them at the proceedings.

Little Shell addressed the Commission asking that Reverend Father J. F. Malo, their Catholic Priest, Bottineau, their attorney, and Judge Burke of Rolette County, to be present on their behalf. The Commission allowed their presence, and Little Shell expressed his hope for a successful settlement of both parties. He then introduced Red Thunder to the commission. In Red Thunder’s address, he told of the inclusion of the mixed-bloods as members of their tribe and described the suffering of his people. In his concluding statements he said:

“We are all glad that our Great Father sent you here and we hope that you will relieve us from starvation, for we have nothing to eat.”

The Commission justified not feeding the people by stating that the Chippewa misunderstood Major Waugh’s letter and he would only feed those selected by the United States government. The Committee suggested that Little Shell stay and help with the rolls. However, Little Shell and his followers left, designating attorney Bottineau to act in their behalf. Bottineau, realizing a great injustice had been done concerning the rolls, requested the commission to give him a list of those excluded from the list, to appeal for them. They never provided him the information. Instead, they hung a list of people rejected from the roll on the church doors on September 24, 1892. Bottineau then requested access to the rolls. The commission agreed, but E. W. Brenner, Farmer in Charge, refused to provide access to Bottineau, only giving numbers of those eligible and numbers of those rejected.

Little Shell was unwilling to give up. He gathered lists from each family containing their family members, so they would be considered for the rolls. One hour before the next meeting of the Commission, they ordered that Little Shell withdraw from the reservation, or they would arrest him. They astonished the people. They felt the absence of Little Shell and Bottineau would be disastrous. In unison they shouted:

“You shall not go” meaning that their attorney Bottineau, should not go, some going so far as to utter, “This is death to us; better meet it now than starve to death.”

After a discussion between Little Shell, his council, Bottineau, and Judge Burke, it was decided they should leave. Waugh’s committee of thirty-two accepted the terms of the agreement. The tribe as a whole did not recognize this Committee. In customary fashion, the Chief appointed the council. Because they did not recognize the committee of thirty-two, they had no right to handle the affairs of the tribe. Upon conclusion of the meetings, the committee of thirty-two realized the grave mistake they had made and reported this to Little Shell. They knew what was taking place but offered no alternative to the situation.

On October 24, 1892, Chief Little Shell and his councilmen filed a protest with Congress against the ratification of the proposed McCumber Agreement. With the assistance of Bottineau, J.B. Ledeqult, special interpreter, and Judge John Burke, the protest outlined the grievances of the Turtle Mountain people. They disagreed with the government’s negotiations with the committee of thirty-two, who were not the recognized Grand Council of the Band. They also protested to the inappropriate conditions of the meeting place, and the threats by Agent Waugh of removing them from their lands. The payment of the settlement was also considered inadequate. It discriminated against the Chippewa. Other treaties and tribes were getting anywhere from .50 cents to $2.50 per acre. In addition, non-Indian lands were valued even higher. The proposed ten cents per acre was unacceptable. Lastly, the agreement lacked sufficient assistance for education of the children. Congress never considered Little Shell’s protest.

Early Reservation Life

The Turtle Mountain Reservation is Established, 1882

It was not until December of 1882 that Congress designated a 24 by 32-mile tract in Rolette County as the Turtle Mountain Reservation for the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa. The government thought they were dealing with about 200 full-blooded Chippewas, but there were more than 1,000 mixed-bloods that they had not counted. The government wanted to allot the members 160 acres as they had done for the non-Indians in the area. However, the Chippewas were against this arrangement and preferred to hold the land in common with all tribal members.

In 1882, President Chester Arthur established the Turtle Mountain Reservation with 22 townships of land. By March of 1884, the original 22 townships were reduced to two townships. All of the best farm land was now open to the public domain.

The Railroad

Between 1858 and 1862, the railroad appeared in parts of Red River country. The man who was responsible for driving the first spike in the first railroad west of St. Paul was William Crooks in 1862. The railroad followed the Red River trails, accelerated the growth of agriculture, and led many settlers to the northwest. It is believed that the railroad colonized much of the west. Grace Flandrau explains:

In all that country west from the Red River, the railroad truly was the pioneer, blazing the way and furnishing the conveyance for colonizing the land. That country never was in any true sense a “covered wagon” country, but was settled from the immigrant train drawn by the locomotive.

Dawes Act of 1887

In 1887, the General Allotment Act, commonly referred as “the Dawes Act,” was passed by Congress. They named it for the chairperson of the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs, Henry L. Dawes. The government believed the Dawes Act to be a final solution to the “Indian problem.” “Congress was convinced that the allotment of land to tribal members would do the following: (1) destroy tribalism and reservations by individualizing Indians on allotments, (2) confer citizenship on all Indians, and (3) educate Indian youth to assure continuation of reforms. . .” (Prucha, 1975, pp. 171–174) The Act resulted in the allotment of lands to individual tribal members. Since there were many more members than lands available, the government allotted lands to tribal members on the Turtle Mountain Reservation, at Trenton, North Dakota, in Montana, and elsewhere in the Dakotas.

Throughout the late 1800s the Turtle Mountain Chippewa endured many hardships. The buffalo, a main source of food for the people, was now reaching extinction. The people throughout certain seasons would experience suffering and starvation. As early as the 1870s, poor conditions were reported in the Turtle Mountains.

Not only had the food supply diminished, there was encroachment of white settlers. On June 25, 1882, a group of white settlers decided to settle in the Turtle Mountains near what is the present-day town of St. John. Under the leadership of Little Shell, 200 Indians rode over to the settlement and informed them they must leave their land. The settlers did move, however. Two of them were U.S. citizens who petitioned Washington to protect them from the Indians. On August 30, 1882, Major Conrad from Fort Totten traveled to the Turtle Mountains with more than forty soldiers. He met with Little Shell and told him that he would kill him if he harmed any of the white settlers. The settlers, after hearing the news from Conrad, moved back onto the reservation on September 3, 1882.

In the mid 1880s, there were severe winter storms and summer droughts. This harsh weather caused many pioneer farms to fail in the Great Plains areas. The influx of Métis from Canada following the second Riel Rebellion caused an overcrowding of the two townships. These circumstances took their toll and in the winter of 1887–1888, and 151 members of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa starved to death.

Harassment of the Chippewa Continues

In 1889 some Turtle Mountain people were raising cattle received from the U.S. government. County officials tried to collect taxes on the cattle. The Chippewas refused to pay. When they refused, they took several head of cattle from them creating a hostile situation between the Chippewa and local officials. The Sheriff of Dunseith, Thomas Flynn, requested assistance from Major McKay of the National Guard. Major McKay and his 1st Battalion headed for the mountains. Because of the quick action of Mr. Salt and E.W. Brenner, they stopped the troop. They had received a telegram from Governor John Miller calling the troops back.

This situation heightened with the encroachment of white settlers. Few choices were left for the Turtle Mountain people. In 1888 Little Shell, Red Thunder, and Henry Poitras sent a letter to Father Genin at Bathgate, North Dakota. The letter was a request for his help and advice. They needed assistance with the illegal taking of lands, and the hunger of their people. Father Genin was a well-known man in the northwest. He devoted more than thirty years as a missionary and priest to the Chippewa and the Dakota of Minnesota and North Dakota. In 1897 he wrote a letter in response to an article printed in the Duluth Journal. The article dealt with the underlying causes of the problem:

I pledge to you my word as a priest who has known these people for over thirty years, that your informant is right, and there can always be found degraded white men who surround and follow the Indians even as wolves used to follow the buffalo herd in our old times, to make them their prey . . . The condition of these people is truly beyond all endurance. I can and will if necessary, furnish you proof of all I say. (Letter from Father Genin to U.S. Commisioner of Indian Affairs, 1897)

Early 1900s

The United States now dealt with Indians through the War Department. Considering the Indian as a military threat, Congress established an Indian agent system in 1896. Through this system, they assigned agents to different tribes whose responsibility it was to maintain friendships among the Indians, carry out treaty obligations, and mediate issues over land. They stationed agents, referred to as “Farmers in Charge,” at small posts in different regions of the country. The agent who served at Turtle Mountain was E. W. Brenner. He was headquartered at Fort Totten.

By 1910, a Bureau of Indian Affairs office was established in Belcourt. The Turtle Mountains now had its own agent. The agent handled weekly business, one day of which was set-aside as “Indian Day.”

In 1919, Indian men, who were not citizens, enlisted in large numbers in the World War I. Citizenship was granted to all Indian people with the passage of the Snyder Act in 1924. This piece of legislation became known as the Indian Citizenship Act and granted citizenship status to all Indian people, born within the territorial limits of the United States.

Works Progress Administration (WPA) Days, 1930s

The drought and Great Depression had a devastating impact on all of America. Accustomed to continuous poverty, struggle, and hunger, the impact on Turtle Mountain Chippewa was not as severely felt. Hardworking and resourceful people, the Chippewa adopted farming and gardening. Gardening was a means of maintaining a livelihood after the decline of their traditional occupations of hunting, trapping, and trading. They raised cattle, pigs, and fowl and supported themselves with limited hunting, trapping, and fishing. Through ingenuity, work was found in a variety of areas such as selling berries, trading and bartering, chopping and selling of wood, farm work, and even collecting medicinal herbs for pharmaceutical companies. Resources were limited and the people continued to struggle economically.

It was under the administration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt that the Works Progress Administration (WPA) Act was passed in 1933. This program offered many economic options for the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa. Jobs were provided for men in road construction and home improvement on the reservation. Construction jobs entailed the building of small two- and three-room houses to replace one-room cabins. Women were given jobs and training in sewing, cooking, canning, and gardening. Some felt the depression was a blessing for tribal members because it opened up job opportunities through the WPA.

Because of allotment and lack of employment opportunities, many Chippewa left the Turtle Mountain region. However, after the WPA program was off to a good start, people began to return. The Indian people in Rolette County numbered 2,400. Ten years later that number was up to 5,000. The work boosted the morale of the people and their standard of living. Most of the jobs provided were of a seasonal type, leaving a big part of the year in unemployment where hardship prevailed.

Indian Reorganization Act of 1934

Congress approved the first constitution of the Turtle Mountain Band in 1932. All of the subsequent revisions made by the tribe were approved by the Department of Interior. The Wheeler-Howard Act, known as the Indian Reorganization Act (IRA) of 1934, was the attempt to undo the damage caused by the earlier allotment acts. The Act was envisioned by John Collier, who became Commissioner of Indian Affairs. This legislation allowed tribes the opportunity to draft their own constitutions and bylaws, to “reorganize” under the authority of IRA and devise their own system of governance. This legislation also provided funds to some tribes to help them in reorganizing. By a vote of the people, the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa chose not to accept the Indian Reorganization Act as its form of government.

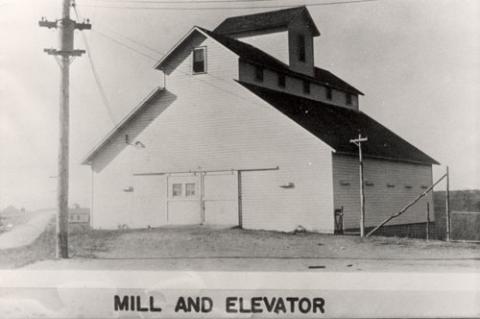

During this time, the Turtle Mountain people, through their resourcefulness, had established and maintained a comfortable community. In 1922, a large mercantile store was built. Known as “the Big Store,” this store, which was situated beside the lumber yard, served as a local gathering place. The town also supported a creamery, a grain elevator, a privately owned gas station, and a lumber yard. The people, returning to the reservation following the depression, required new opportunities. It was during this time that a hospital was built to accommodate the needs of the people.

Turtle Mountain Pembina Band Claim

Congress established the U.S. Court of Claims in 1948. This legislation allowed the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa to file a claim against the government for unfair market value of lands ceded under the McCumber Agreement. The Chippewa pursued this claim from 1892 to 1975. For nearly a century, Chippewa people gathered, discussed, and journeyed to Washington, D.C. to gain redress. The payment of expenses and countless years of time came from the hearts of the Pembina descendants.

Relocation Act, 1952

The relocation program was established by the Bureau of Indian Affairs in 1952. This program encouraged relocating Indians to urban areas in search of employment. The program offered vocational training, travel monies, moving expenses, one year of medical care, and assistance in finding employment. By the 1960s, 2,900 Chippewa had moved away from the reservation. People were moving to California, Illinois, Washington, and other urban areas. Many Chippewa, who moved away at one time or another, returned. This rate of relocation continued until President John Kennedy’s “War on Poverty.” Many Chippewa, who took advantage of the relocation program, continued to return as the economy of the country fluctuated and urban communities decayed. The longing for family and cultural ties also drew them home.

Proposed Termination of 1954

In 1954, Congress attempted to end the reservation system. Two men in particular, Arthur Walkings and E. Y. Berry, served on Indian Affairs committees. Congressman Walkings proposed the mainstreaming and assimilation of tribal people, thus freeing the federal government from its constitutionally-bound trust responsibility to tribal nations.

Before the passage of this bill, Congress undertook three studies. These studies swayed Congress away from federal policies supported by the government under the “Reorganization Act.” This shift in federal policy openly encouraged termination. One report, the Zimmerman Report, proposed a four-part formula which assessed and ranked the tribes in terms of their relative level of economic readiness. They determined that ten (10) tribes were ready for termination. The Turtle Mountain Band was one of the names on the list of ten tribes to be terminated.

By 1954, Congress made it known to tribes that they were holding hearings concerning their termination. The Turtle Mountain Band raised funds locally to send a delegation to Washington. Tribal Chairperson Patrick Gourneau testified that the Turtle Mountain people were unprepared economically, still living in poverty, and that such a move would be devastating. Following the testimony of the Turtle Mountain group, the subcommittee decided that the Turtle Mountain Band was not economically self-sufficient, and was dropped from the list. Perhaps because the Turtle Mountain people have always been resourceful, Congress made a preliminary determination, based upon the BIA Superintendents’ reports, to terminate the Band. They did not consider the fact that the Chippewa were still poverty stricken, occupied an extremely limited land base, and suffered from low education levels and high unemployment.

War on Poverty, 1960s

Poverty was, and still remains, a concern for the Turtle Mountain people. In 1955 Dr. David Delorme described the socioeconomic conditions at Turtle Mountain as a “rural slum.” Economic deprivation created poverty conditions requiring rectification. President Kennedy addressed many concerns involving civil rights and social reform. Even though Kennedy was assassinated in 1963, his successor, Lyndon B. Johnson, used his influence to put Kennedy’s reform into action. Several efforts under the Johnson Administration provided new opportunity for Tribes. Congress passed laws forbidding racial discrimination. The President, in 1964, declared a “War on Poverty” and the “Great Society” reform was implemented.

The Economic Opportunity Act of 1965 opened the door to “self-determination.” The Economic Opportunity Act directed financial aid into the hands of tribal governments. Prior to this, monies were filtered through the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Now, for the first time, Tribal governments would handle their own budgeted monies. The limited powers of Tribal councils were increased and supported by the passage of the Indian Civil Rights Act of 1968. This legislation affirmed the rights of Tribal Nations and extended some provisions of the Bill of Rights to Indian people that had been afforded to all American citizens.

Self Determination

The idea of self determination was first addressed by President Lyndon Johnson in an address to Congress. Indian leaders advocated for a change from termination to self control, which meant, at some future point, tribes would assume control over their own affairs without bureaucratic interference. This did not mean the federal government would have less responsibility to tribes or end their federal trust relationship. President Richard Nixon continued to support Indian self-determination. In 1975, Congress passed the Indian Self-determination and Education Assistance Act. This public law formally recognized the right of autonomy of tribal nations as a national Indian policy.

Tribal Community College Act, 1978 Turtle Mountain Community College

Growing awareness that more college-educated tribal people were needed to provide necessary and effective services on the Turtle Mountain Chippewa Reservation led to efforts in the 1960s to bring college courses to the reservation. Efforts by local Indian citizens resulted in a charter from the Tribe to establish the Turtle Mountain Community College (TMCC) in 1972. In September of 1976, the college received a Certificate of Incorporation from the State of North Dakota. The founding mission of the college was to provide higher education services for tribal members, preserve and promote the history and culture of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa, and provide leadership and community service to the reservation. TMCC offers Associate of Arts, Associate of Science, Associate of Applied Science, and Vocational Certificate programs.

In 1978, the Tribal Controlled College Assistance Act was significant in that it provided the financial support required to implement the Tribe’s higher educational goals. Land grant status was granted to the institution in 1994. Another achievement occurred in 1996 when President Bill Clinton signed the Executive Order directing that all federal agencies support tribal controlled colleges.

Turtle Mountain Community College is fully accredited. The college became a candidate for accreditation in 1980, and received full accreditation from the North Central Association of Colleges and Schools (NCA) in 1984. In 2003, TMCC was recommended by a visiting team from the Higher Learning Commission of the NCA for 10 more years of accreditation.

In 2007, more than 650 students were enrolled at Turtle Mountain Community College. To date more than 1,000 tribal members have graduated from the institution. Approximately 300 of them have gone on to earn bachelors and advanced degrees. While the reservation experiences high unemployment, the graduates of Turtle Mountain Community College experience a much lower unemployment rate.

In the spring of 1997, a ground-breaking ceremony was held and work began on a new, $10 million facility designed to serve 800 students. Those who attended witnessed what many have called sacred messages…there were some special things happening around the sun, and an eagle floated above during the ceremony.

1982 Treaty Settlement

In 1980, the U.S. Court of Claims awarded a judgment to the Pembina Band of Chippewa for $52.5 million stemming from the McCumber Agreement. This payment (dockets numbered 113, 191, 221, and 246), was payment for more than 8 million acres of land in north central North Dakota. The ninety-seventh Congress of the United States passed an act known as Public law 97-403 in December of 1982. The Act provided for the use and distribution of funds awarded to five Pembina Indian Bands. Awardees included the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa, Rocky Boy Chippewa-Cree of Montana, White Earth Pembina Band of the Minnesota Chippewa, Little Shell Band of Chippewa (Montana), and various Pembina descendants.

Congress appropriated funds to the Bureau of Indian Affairs whose responsibility it was to certify eligibility and distribution of funds. The Bureau distributed 80 percent of the funds to eligible members and held 20 percent in trust for the benefit of the Turtle Mountain Band. The Act directed the Secretary of the Interior to authorize the Tribal Council to use the interest and investment income accrued from the 20 percent set-aside for economic development. The McCumber Agreement Award (for the Ten Cent Treaty) was invested by the BIA Branch of Investments. In a period of eight years the invested money grew to more than $102 million.

LePay

“LePay” is a French word meaning payment. Lands treated and agreed upon for nearly 100 years had not been justly compensated. The people, who were now receiving the payment, expressed mixed feelings. They were reminded of the sufferings that their ancestors endured while they waited in anticipation of “LePay.” Writing to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Indian Agent F. O. Getchell described the torment of the Turtle Mountain people:

Such is the place and such are nearly 2,000 of the people who are besieged in their mountain fastness by the peaceful army of the plow that has settled their hunting grounds. Here they are held in worst than bondage while they are waiting, for a settlement with the government for the land so settled by the plowmen, waiting for a day that never comes. While their chance in the land that was their own is fading, fading away from them. God pity their patient waiting and appoint that it may not have been in vain.(Senate Doc. No. 239, 54th Congress, 1st Session)

Payment to the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa came through the distribution of three treaty checks. In 1984, members whose names appeared on the 1940 base roll, from the Old Crossing Treaty, received the first payment of about $43.81. They issued a partial payment on June 16, 1988, for $1,721.50, and a final payment on February 1994 of approximately $1,200. Tribal members of one-fourth or more degree of Indian blood and born on or before December 31, 1982 and enrolled before December 30, 1983 were entitled to share in the claim as an enrolled member. Minors, entitled to the treaty payment, have monies held in trust until their 18th birthday. The Bureau completed total distribution to this group in 2000.

Trenton Indian Service Area

Around the early 1800s, the supply of food and game on the plains had grown scarce. As a result, the seasonal hunting of the Chippewa expanded westward in search of game. This took them into the confluence area of the Yellowstone and Missouri Rivers, a major crossing point of many other Indian tribes that hunted and traded through the territory. Fort Union, which the American Fur Company had established around 1828, controlled most of the Northwest trade. Around 1867, after the fur trade had declined, they abandoned Fort Union.

Fort Buford was established in 1866, at the juncture of the two rivers. It served as a supply headquarters for military campaigns against the Sioux. Many Indian people continued to hunt and trap around the area. In 1886, following the implementation of the General Allotment Act, there was not sufficient land available on the Turtle Mountain Reservation for allotments for all tribal members. Many had continued their migratory hunting patterns into western North Dakota and Montana. The Dawes Commission, finding more Turtle Mountain tribal members than there was land, allotted nearly 6,698 acres in western North Dakota, in Williams County, to tribal members. During this time, many Turtle Mountain Chippewa, who had hunted in the Williams County area took their allotments, and moved to the Fort Buford area. Fort Buford was disbanded on October 21, 1895. Having settled and prospered on their allotments, the Turtle Mountain people continued to live in the area.

In 1884, when the Great Northern Railway founded the town of Trenton, the community quickly became headquarters for the Turtle Mountain people who owned land near it. Trenton benefitted from the employment caused by the railroad construction. A growing and prosperous community, Trenton boasted a variety of mercantile and grocery stores, blacksmith shops, elevators, and other establishments. Turtle Mountain people sold wood and coal to the workers. (United Tribes, 1975)

As the railroad industry declined, the Turtle Mountain people migrated to other areas in search of work. Many never returned to the Fort Buford area. During the early part of the 1900s, a group of Turtle Mountain Chippewa continued to live in the area. During the 1930s, many found work in government-sponsored programs, and worked on various development projects, including the Buford-Trenton Irrigation district. They maintained their ties with the Turtle Mountain Band, but received no assistance from them.

When crude oil was discovered in the early 1950s near Tioga, North Dakota, the resulting oil boom again created a flourishing environment for communities such as Williston and Trenton. The Turtle Mountain Chippewa again experienced prosperity. As the young people grew up, some began to move to the Williston area.

By the early 1970s, the Trenton community had become a community integrated with Indians and non-Indians. The population in Trenton during this time comprised approximately 66 white and 188 Indian families. Additional Turtle Mountain families moved to Williston and other nearby communities. (United Tribes, 1975, p. 62)

Because much of their work was greatly dependent upon the local economy, seasonal unemployment was a chronic concern. In the spring of 1972, the people of Williams County formed the Fort Buford Indian Development Corporation. The purpose was to qualify for several economic recovery programs, and to insure the future of the people. They established the corporation, and through it received several housing, health service, and employment programs.

During the mid 1970s, many of the Chippewa were concerned with maintaining and preserving their identity as Turtle Mountain Chippewa and their connection to the heritage and culture. The Fort Buford Development Corporation sought designation as a formal extension of the Turtle Mountain Band. Designated as the “Trenton Indian Service Area” (TISA), it was established by Ordinance 28 of the Turtle Mountain Tribal Council on March 25, 1975.

As a result, the people at Trenton formed their own governing structure. The Trenton Indian Service area lies in the northwest corner of North Dakota, and the northeast section of Montana. Much of the area is in Williams and Divide Counties, and the northern portion of McKenzie County. The area covers approximately 6, 200 square miles, is bounded on the north by the Canadian border and on the west by the Fort Peck Indian Reservation in Montana.

Trenton, the center of operation for TISA, is located 14 miles southwest of Williston, North Dakota. A board of directors governs the Trenton Indian Service Area, which consists of seven members, two from each of the three districts, and one chairperson. The chairperson is elected at-large. The enrolled members of the Trenton Indian Service Area elect the board members. The total service population of TISA is approximately 3,000; enrolled members number 2,600. Today, the Turtle Mountain Chippewas at Trenton celebrate Trenton Indian Service Area Days each July.