Introduction

The USS North Dakota was launched on November 10, 1908. About 150 of the most important political and business figures from the state of North Dakota traveled to Quincy, Massachusetts to honor the ship at the ceremony. She had been named for this state following a long-standing tradition of naming ships for each state in the Union.

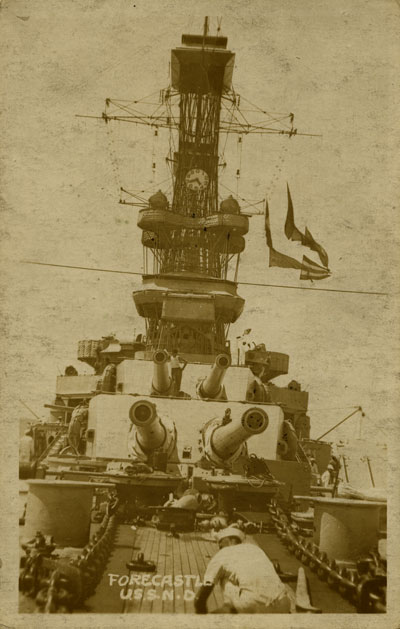

This new dreadnought (DRED-NAWT), the first all-big-gun ship in the US Navy, was the biggest, heaviest, and fastest battleship yet built by any navy in the world. Though it was modeled after a British battleship, the design came from an American Navy officer, Commander Homer C. Poundstone. The North Dakota had ten 12 inch guns which could be turned to face the enemy in any direction. The sailors were also trained to repel torpedo attacks and possible attacks from airplanes which were used as military weapons by 1915.

The USS North Dakota was completed and commissioned on April 11, 1910. Over the next thirteen years, she sailed along the east coast of the United States, the Caribbean Sea, the coast of Mexico, northern Europe, and to Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. She patrolled the east coast from Virginia to Long Island during World War I, and trained midshipmen from the US Naval Academy. She toured ports on the Mediterranean Sea in 1919. Her crew took honors in target practice on the open sea, hitting targets as far as 10 miles away at a rate exceeding thirty per cent. The ship, however, was also troubled by engine breakdowns including a major explosion and fire in September 1910.

2002-P-15-Album2-P69b.

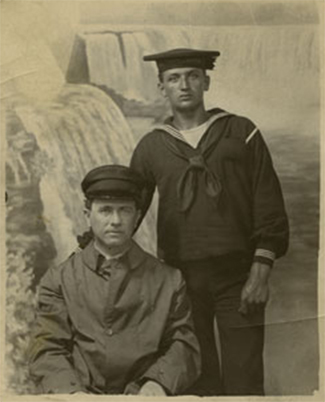

The ship was home to more than 900 officers and enlisted men. The officers, usually educated at the Naval Academy, were leaders who headed up every division of the ship. The enlisted men were the ones who took orders from the officers. Most had enlisted for four years, but some would spend their entire careers in the Navy.

With so many men on board, the ship became a small city at sea. All of the personal needs of the men had to be met on board, and the ship’s work had to be completed in an orderly and timely manner. Very few letters or other documents remain from the men who served on the USS North Dakota, but there are many small pieces of evidence, or incomplete pieces of information, that help us understand how the men went about their work, how they spent their leisure time, and what it was like to live aboard a large and powerful battleship. The evidence about life on the ship mostly comes from newspaper articles published while the ship was active; other evidence can be seen in photographs or a few documents that were produced on the ship.

The USS North Dakota, which never saw combat, was taken out of service in 1923 to satisfy the requirements of the Washington Naval Arms Limitation Treaty which tried to put an end to the naval arms race of the early twentieth century. In 1931, the ship was taken apart for scrap, but we can still study her history and discover what life was like in a floating community.

The ship was home to more than 900 officers and enlisted men. The officers, usually educated at the Naval Academy, were leaders who headed up every division of the ship. The enlisted men were the ones who took orders from the officers. Most had enlisted for four years, but some would spend their entire careers in the Navy.

With so many men on board, the ship became a small city at sea. All of the personal needs of the men had to be met on board, and the ship’s work had to be completed in an orderly and timely manner. Very few letters or other documents remain from the men who served on the USS North Dakota, but there are many small pieces of evidence, or incomplete pieces of information, that help us understand how the men went about their work, how they spent their leisure time, and what it was like to live aboard a large and powerful battleship. The evidence about life on the ship mostly comes from newspaper articles published while the ship was active; other evidence can be seen in photographs or a few documents that were produced on the ship.

The USS North Dakota, which never saw combat, was taken out of service in 1923 to satisfy the requirements of the Washington Naval Arms Limitation Treaty which tried to put an end to the naval arms race of the early twentieth century. In 1931, the ship was taken apart for scrap, but we can still study her history and discover what life was like in a floating community.

Work

The men of the USS North Dakota had regular duties when the ship was at sea and in port. The ship at sea had to provide for all the needs of a community that had a population larger than that of many North Dakota towns. The work can be divided into two classifications: the jobs of enlisted men and the jobs of officers.

The work of operating and maintaining the two Curtis turbine engines was assigned to enlisted men. The engines usually ran on coal, though they could run on fuel oil. The “coal passers” shoveled coal from the storage bins into the engines. This was a dirty and hard job that proved to be dangerous as well. These engineers worked in a room with no daylight, poor air quality, and high temperatures.

2002-P-15-Album2-P52b.

Preparing meals was the job of enlisted men. Cooks and their helpers worked in high temperatures managing huge kettles and sides of beef and pork. Philippino sailors who were distinguished by their status as citizens of a nation under the control of the US, their dark skin color, and their lack of fluency in speaking English often worked as mess assistants. Their jobs were to serve and clean up after meals.

Stewards were enlisted men who attended the officers by cleaning their quarters and providing them with necessary services. When the ship was preparing to fire its big guns, the stewards had to secure all breakable items such as mirrors and lamps in the officers’ quarters to prevent them being knocked over by the recoil when the guns were fired. Even the ship’s piano had to be raised from the floor and supported by ropes because otherwise the strings would break under the stress of the guns’ recoil.

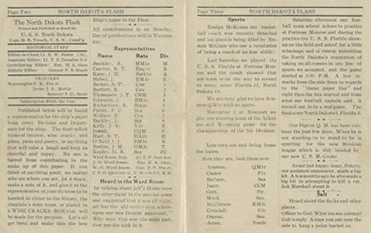

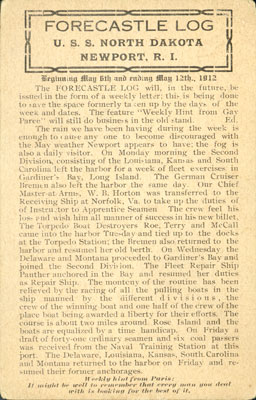

A variety of skilled and semi-skilled jobs were found on the ship, too. Printers published the ship’s newsletter, The Flash or the earlier Forecastle Log, as well as smaller publications including notices about the week’s entertainment. Blacksmiths forged metal pieces for repairs on the ship. Radio operators maintained the ship’s communications with other ships and with on-shore offices.

It was much longer than the Forecastle Log and much more entertaining.

It offers gossip, news of sports competitions, and an inspirational essay.

Note that the newsletter was written and edited by officers,

but printed by enlisted men. 2002-P-15-Album2-P58a.

on board the North Dakota in 1912. 2002-P-15-Album2-P68b.

Officers included the ship’s captain, navigator, and men who served as leaders in every office and operation on the ship. Many of them were trained as engineers and understood every detail of the ship’s mechanical operation.

In addition, like most land-based communities, the ship also had a doctor and dentist (both officers). The doctor was necessary for small and large health problems. In June 1915, as the North Dakota sailed into the shipyards for repairs, several sailors were being treated for diphtheria causing the ship to be quarantined.

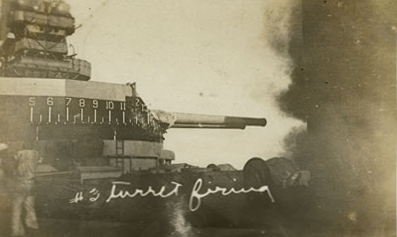

The most glamorous job on the North Dakota was maintaining and firing the big guns. Each gun was assigned to a team consisting of enlisted men of different ranks (or “rates”) and an officer, usually a lieutenant or ensign. The ship was always prepared for combat, but the North Dakota was never to engage in battle. In the meantime, the business of the ship’s men was to maintain the ship and its floating community in good health, good spirits, and good condition.

School

The headline on the Saint Paul Pioneer Press article read: Every Battleship a Schoolroom! Every Jack for a Pupil, Under Educational Plan of Secretary Daniels, to Make Navy Place Where Men May Study Trade of Profession While Learning to Fight. The article went on to describe the educational program recommended by Secretary of the Navy, Josephus Daniels, to help sailors avoid “rusting out” or becoming bored with Navy routine. Daniels wanted men who enlisted for a four year tour of duty to be better men at the end of their enlistment.

In 1914, many communities across the United States were making a strong commitment to education for everyone, especially the poor, whose education often had been neglected in the past. Secretary Daniels was part of the education movement because he wanted every Navy enlisted man to know how to read, write, and “cipher” (do arithmetic) as well as to learn a trade.

Daniels was convinced that educated men would not mutiny (rise up against their officers) nor desert their duty. He hoped that his program would have sailors enlist as laborers and become skilled workers before their discharge. Sailors who refused the training would be stuck in the “mean and dirty jobs” of the ship. Daniels also thought the program would make the Navy more appealing to men looking for a position in life. The teachers were the officers, all highly educated men, most of whom were graduates of the Naval Academy at Annapolis, Maryland.

A few months after Daniels made his statement, officers of the North Dakota had set aside one hour and fifteen minutes every day for study. Commander Jackson explained the system on January 21, 1914:

All of the officers, except the Captain, commander, and navigator of each vessel, act as instructors in the elementary subjects and in higher mathematics. . . . Thus, on the North Dakota we have thirty-four officers, graduates of Annapolis, to give tuition to the men. All members of the crew, of whatever grade or branch of service, are compelled to take up a course of study. The classes are conducted from 1:15 to 2:30 P.M.

Another officer described how the ship created classrooms:

Of course, this is a battleship and not a schoolhouse, and the work is conducted under some difficulties. When I want a blackboard for example, I send word to the ship’s carpenter, and he meets the requisition by nailing together a few pieces of board, planing them off, and giving the finished product a coat of black paint. Most of the officers have equipped themselves with blackboard 6 by 3 feet in dimension.

This officer went on to describe his students and their studies. He assigned his students to write essays about why they enlisted in the Navy. Most of his students were Filipinos, or men from the Phillipines, an Asian nation which was at that time under the rule of the United States. They served as mess (meal) attendants in the ship’s kitchens. Though they had had a good basic education as children in the Philippines, they did not have a strong command of English. In their essays on the topic, Why I Joined the Navy, one student wrote: “I joined navy for reglum rashuns 3 times dayly.” Another stated that he joined to “serve woes of my humans rase.” In their effort to express themselves in English, they tell of their own struggles (securing three good meals a day) and their desire to make the world a better place by trying, through their naval service, to address the world’s troubles (“woes”).

Other sailors who had a good basic education were able to take more advanced courses. An officer explained:

Such men [who have a good education] are permitted to take up technical studies including electrical engineering, mechanical engineering, stenography, ordnance, higher mathematics, and navigation. The pay officers conduct classes in bookkeeping and in accounting. In addition such trades as plumbing, gas [pipe] fitting, printing, carpentry and mechanics are taught to those men desiring such instruction and who are deemed capable of undertaking such practical courses.

The only textbooks used are those prescribed by the order of the Navy Department for teaching arithmetic, writing, spelling, geography, and American history. Men taking up other courses are obliged to obtain their tuition through lectures and practical demonstrations or from text-books purchased by themselves. Some of the enlisted men are pursuing courses in recognized correspondence schools, and these are excused from the regular school work and the hour is set aside for them for study purposes. These men receive advice and assistance in their studies from the officers as they require it.

Though the United States has always promoted education as the foundation for a healthy democracy, the Navy’s leading battleship was not a democracy and sailors did not study in mixed groups. Chief Petty Officers were educated separately from lower petty officers who might be educated with the enlisted men, depending on their educational level. Discipline and the privileges of rank were maintained by segregation of the students according to rank as well as their educational background.

Sources: St. Paul Pioneer Press 21 September 1913 “Naval Men Dazed by School Rules,” New York Times 22 January 1914

Athletics

Athletic contests helped the enlisted men, petty officers, and officers to pass the time. Physical activity kept the men in good condition, but playing as a team representing their ship helped to foster good feelings and team spirit among the men in all their shipboard work.

While in port, sailors formed teams for baseball, football, and basketball. They also competed in gymnastics and track and field. On September 30, 1913, the New York Times reported on the basketball game the enlisted men of the North Dakota played against its sister ship, the Delaware for the Naval YMCA championship. The North Dakota team defeated the Delaware team by a score of 39 to 21. A forward named Gullickson scored 20 of the North Dakota’s points.

The same day as the basketball game, men of the North Dakota also participated in gymnastics at the Naval YMCA gym in Brooklyn. The North Dakota had an excellent gymnast by the name of C. A. Danneman who tied for second in the parallel bars; tied for first in flying rings with his fellow North Dakota shipmate C. B. Forest, and took first place on the horse and the horizontal bars. C. B. Forest also placed in all events.

Some ports had baseball diamonds, and in these ports, baseball games were popular. Whenever the ship docked at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba the sailors were able to take advantage of the large sports complex that included a baseball diamond, bleachers, and a canteen where sailors could buy soft drinks and other refreshments.

Officers and enlisted men watch the North Dakota’s baseball team play at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba.

2002-P-15-Album1-016.

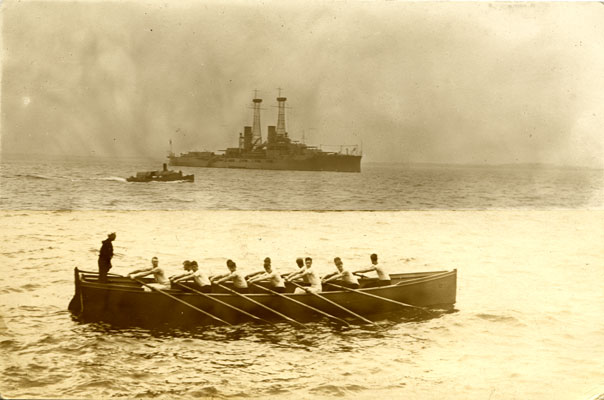

The USS North Dakota is seen in the background of this photograph of the ship’s rowing team.

2002-P-15-Album2-P28b.

Another sport that was popular with sailors was rowing. The North Dakota had a rowing team composed of Chief Petty Officers (CPOs) that competed with boats from other ships. No record has been preserved about the ranking of the North Dakota’s CPOs in this competition, but their pride in their sport is apparent in the photograph of the team.

Members of the North Dakota’s CPO race-boat team pose for a formal portrait.

CPOs are not officers, but hold the highest rank of enlisted men. 2002-P-15-Album2-P21a.

Social Life

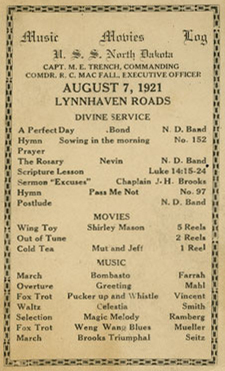

know about worship services, movies (including the popular cartoon “Mutt and Jeff”),

and music on a Sunday. In port, the men may have had free time to enjoy these activities.

2002-P-15-Album2-P56b.

In the floating community of the North Dakota, the weekly routine was occasionally interrupted for pleasure and social events such as musical presentations by the ship’s band, worship services (only Christian services were held), and silent movies or cartoons. Entertainment was very similar to what would be available if the sailors were on shore. Very likely, except for worship services, none of these social events would have taken place on ships before 1913. In the old Navy, sailors entertained themselves by carving wood or ivory, knitting, sewing, and singing or playing musical instruments. The new Navy, which the North Dakota proudly represented, provided sailors with more activities to pass the time.

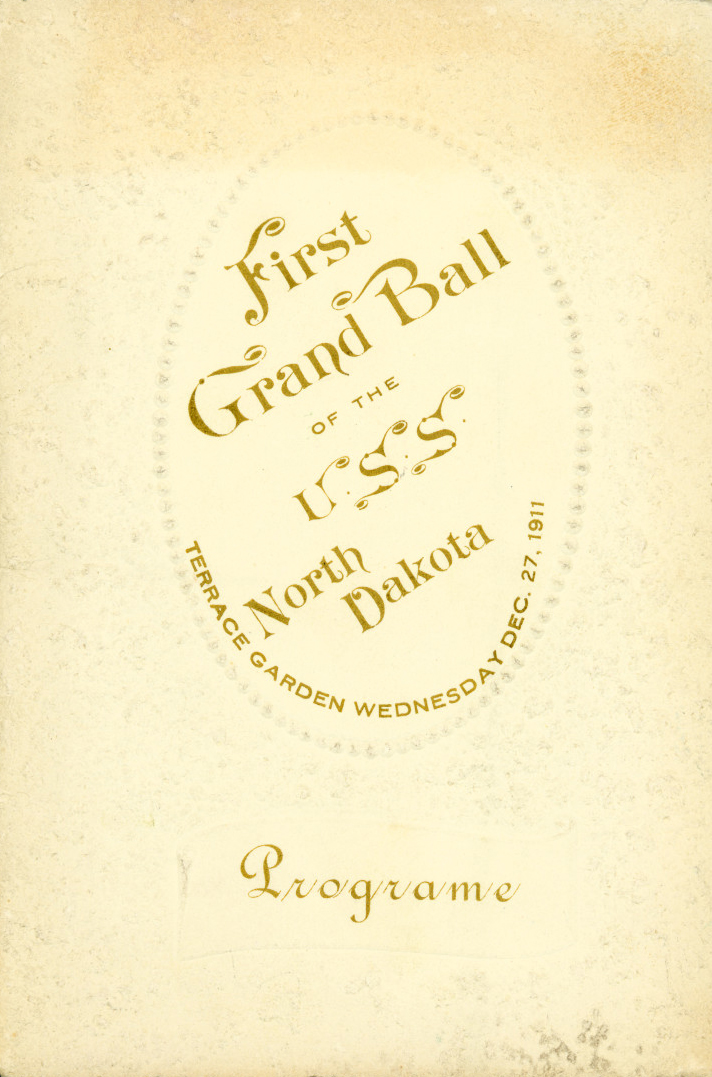

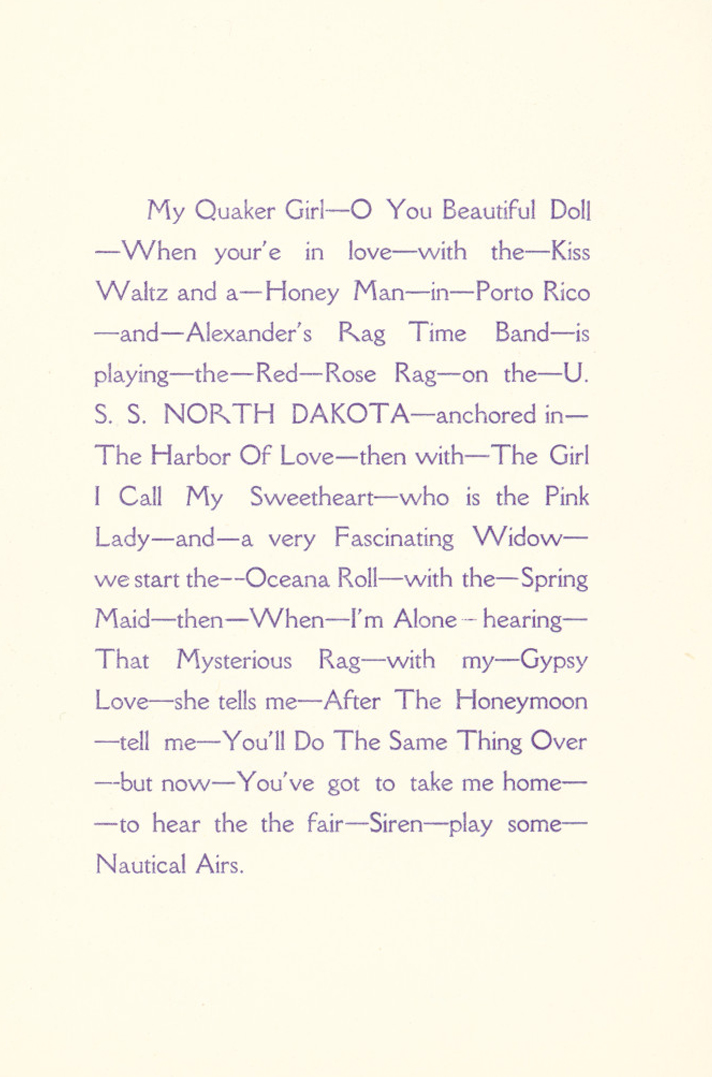

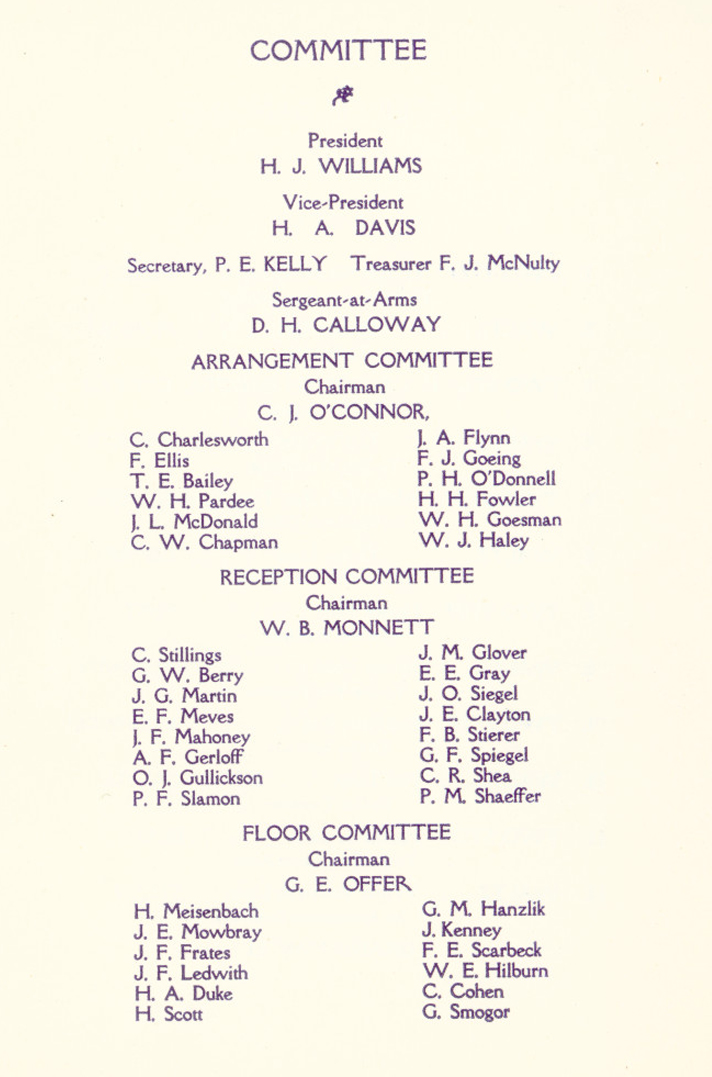

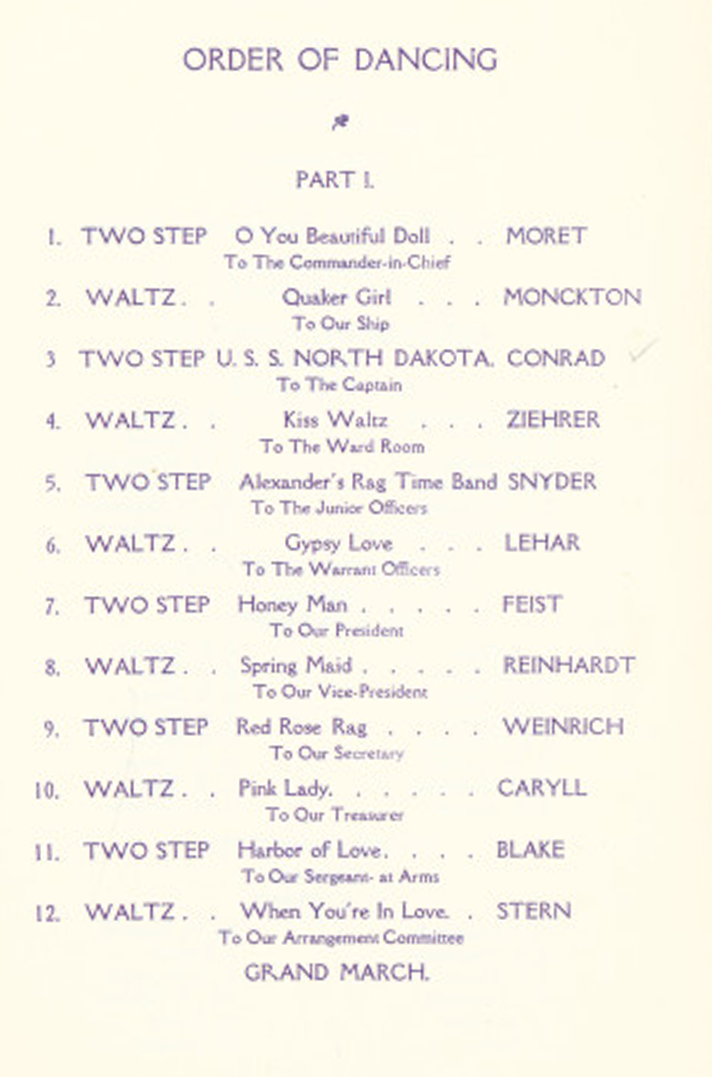

The new Navy, however, maintained the important segregation between officers and enlisted men. For instance, if officers engaged in sports, they would have had other officers as teammates and opponents. Of the records remaining from the USS North Dakota, we have one document of a social event open only to officers - the USS North Dakota Ball. The ball was held on land while the ship was in port in order for the officers to invite ladies as their guests.

A program from this ball lists the songs played for the dance including the “Oceana Roll”, “After the Honeymoon”, and “USS North Dakota” – a two-step. At the back of the program is the dance card of the officer who kept this program as a memento of that occasion. Here he wrote in the names of the ladies who had agreed to dance with him during the evening.

opens with a humorous essay created by stringing together the titles of the songs with a few phrases.

The elaborate arrangements for the ball were overseen by committees of officers.

The young officer who saved this program seemed to favor dancing with “Pat.”

2002-P-15-Album2-P66b.

Crossing the Line celebration. Note King Neptune

(third from right, second row) and Davy Jones (fifth from right, second row)

among the characters. 2002-P-15-Album2-P26b.

Note the African American man in the pool with his back to the camera,

and another African American man waiting for his turn along the side of the pool to the right.

Officers can be seen observing the fun. 2002-P-15-Album2-P20b.

The traditions of the officers’ ball were ancient and very strict, but the ball was one place that young officers could learn and practice the social skills that would help them move up in rank, and possibly meet a young woman who would like to be married to a Navy officer.

Officers would not have mingled with enlisted men at most social events because the Navy believed that discipline was best maintained by the separation of officers and enlisted men. However, one particular and exceptional event brought all the men of the ship together in a bonding ritual that was thousands of years old. When the ship crossed the equator, a passage known as “Crossing the Line”, pollywogs (those who had not previously crossed the equator) would be initiated by a series of activities that took a day or more to conclude. Even senior officers would be included in the rowdy celebration. The final event involved creating a pool of water on the deck and the dunking of pollywogs in the pool. Among the characters that governed the celebration were shellbacks (those who had previously crossed the line) dressed as King Neptune, Davy Jones, and others.

The Crossing the Line party on the North Dakota was celebrated by everyone aboard the ship. Officers appeared in costume and some are visible in the photographs observing the dunking. Most interesting in the photographs are the African American sailors among the pollywogs. All of the United States’ Armed Forces were racially segregated until 1948, but on a floating community such as the battleship North Dakota, segregation was imperfect. Though African American sailors were probably assigned to the most demeaning work and had few opportunities for advancement, they were present for the Crossing the Line celebration and received their cards identifying them as shellbacks along with the rest.

Fire and Engine Troubles

At no time was the community feeling aboard the North Dakota tested more seriously than on the occasion of the fire. It was September 8, 1910, and the North Dakota had been fit for sea duty for only a few months. She was returning with her relatively young and inexperienced crew to Hampton Roads, Virginia after fleet exercises and was running on fuel oil. A fire broke out around 10:30 a.m. in the fuel oil stored in Room No. 3. Captain Gleaves ordered the ship to drop out of formation so as not to endanger the other ships of the division. Immediately he also gave two sets of orders: put out the fire, and retrieve the dead and injured from the engine room.

While dense black smoke poured out of the ventilators and hatchways (doors to the lower levels of the ship), the fire was dampened by flooding the engine room and the oil storage area with sea water. The hold of the ship filled with nine feet of water, but the fire continued to burn above that level.

Without the engines, the pumps could not be operated to put out the rest of the fire. The Commander in Chief of the Fleet, Admiral Schroeder, ordered a tugboat and the USS New Hampshire to stand by the North Dakota to give all aid possible. The tugboat pumped water onto the fires burning above the flooded engine room. For about one hour, the North Dakota was in grave danger of exploding because the powder magazine (gun powder storeroom) was located just above the fire. Fortunately, the flames did not reach the gun powder.

Later in the day, the North Dakota was able to put four boilers back into service. With the little power they provided, the ship was able to raise the anchors and steam slowly into port.

In spite of the quick efforts to put out the flames, three men, Joseph Schmidt, Robert Gilmore, and Joseph Strait, died in the fire. All were enlisted men who held the job of coal passer. Ten men, including one officer, were injured and were moved to a hospital ship, the USS Solace, for treatment before being transferred to a hospital in Virginia.

At the board of inquiry, Lieutenant Commander Orin G. Murfin, who sustained burns in the fire, testified that he was in the engine room and ordered the room abandoned when he saw a flash of flame run along the oil lines. But the fire quickly grew and filled the room with gasses and flames preventing three of the men from escaping the fire room.

Ten men were honored for heroic actions in the fire. Thomas Davis, John Quinlan, George Ellis, and Arnold J. Smith received warm commendations. Six men were awarded the Medal of Honor for “extraordinary heroism.” They were Thomas Stanton, Karl Westa, Patrick Reid, August Holz, Charles Roberts, and Harry Lipscomb. They also received a one-hundred dollar bonus. Davis, Quinlan, Ellis, and Smith closed off the engine fires in a fire room where the heat was so intense they had to be sprayed with fire hoses to avoid dying of the heat. Stanton, Westa, Reid, Holz, Roberts, and Lipscomb were honored for entering the burning engine room to put out the fire. They also removed the dead through waist-deep water in intense heat and dense smoke. Charles Roberts, a machinist’s mate, was overcome by smoke.

The board of inquiry found that a leak in the oil pipes had led to the fire. The crew repaired the damage, and the ship rejoined the fleet by September 29. The Navy declared that the fire was not due to a flawed design – many ships around the world sailed with similar designs. The fire did raise the question of the safety of fuel oil, but the Navy declared that it would not abandon that form of fuel. Instead, the Navy made efforts to protect the powder magazines from the heat and possible fires in the engine rooms.

This fire – not the last that the North Dakota would experience – tested the men and prepared them to deal with future emergencies. It also called upon the officers to apply everything they knew about the ship to the effort to save her. The newspapers reported that “realizing this danger – they worked coolly and with great courage. Capt. Gleaves and every officer aboard fought flames shoulder to shoulder with the men, and when the danger had passed they were as grimy as [coal] stokers.”

Historical records give us very little information about the men who died in the fire. We know little more than that Joseph Schmidt was from Brooklyn, New York; Robert Gilmore was from Connecticut, and Joseph Strait enlisted in Michigan.

Before World War II (1941 – 1945) it was possible to earn the Medal of Honor for bravery in non-combat situations which was the case for these six men. Charles Roberts was born in 1882 and died in 1957. Harry Lipscomb was born in Washington, D.C., in 1878 and died in 1926. He married, and was buried in Arlington National Cemetery. August Holz was born in St. Louis, Missouri in 1871. He died in Long Island, New York in 1935. Thomas Stanton was born in Ireland in 1869, but entered the Navy from Rhode Island. He lived until 1950. Karl Westa was born in Norway in 1875 and lived until 1949. He, too, is buried in Arlington National Cemetery. There is no information available about Patrick Reid.

Unfortunately, the North Dakota had another fire and one more death. After repairs to the damages from the September 8 fire, the ship sailed with the fleet to England and France. On December 14, 1910, an explosion in the coal bunkers burned a sailor identified only as Evans. Evans died of the burns shortly after, but little more was mentioned in the newspapers about the event.

The North Dakota continued to have trouble with the Curtis turbine engines. In February 1915, the engines were damaged while returning from Cuba. In June 1915, the North Dakota was ordered into a shipyard where the engines were to be repaired or replaced in a major overhaul to the satisfaction of the engineer officers who found these turbines to be unreliable.

Engine trouble turned out to be the North Dakota’s greatest failing. When she was running well, she could operate efficiently and at great speed. But when troubles came, they tested the strength, courage, and devotion to duty of all members of this ship’s community.

Source: New York Times, September 9, 1910

Gunnery Practice

the most powerful ship in the world when it went to sea in 1910.

Men who tracked the accuracy of the shells fired,

stood on platforms at the top of the two spider or basket masts.

2002-P-15-Album2-P22a.

On October 31, 1910 shortly after recovering from the first fire, the USS North Dakota entered gunnery competition where she placed 6th out of 16 ships in firing at targets between 6500 and 10,000 yards distant. The winner that year, was North Dakota’s sister ship, the USS Delaware.

Over the next few years, the men of the North Dakota practiced loading, firing, and hitting the targets. Once considered drudgery, in the modern Navy gunnery practice was considered to be “the greatest game in the world” according to one officer. The excitement and sense of competition was shared by the enlisted men and the officers.

The battleships practiced firing on partially sunken vessels and on canvas targets. Some practice was at long range (11,000 yards or 6.25 miles) and some at close range of 2500 to 3000 yards (between 1 and 2 miles).

When one loading crew practiced, they were timed by the officer in charge of the gun. The first test with dummy ammunition took 15 seconds; the officer declared the effort “rotten.” They practiced again, reducing the time to 12 seconds. It was still not good enough. The third effort resulted in a time of 10 seconds. The officer praised the men, saying “Bully, lads – that will do.”

Gunnery practice took place at night and in the daytime. On one occasion during night practice, the ship was shooting at canvas targets. The targets were retrieved and laid on the deck so the holes could be counted. Even the enlisted men who were not assigned to gun duty stayed up late to learn the results. Officers watched, too. To the great “enthusiasm of the ships’ company,” the North Dakota had hit 98 out of 120 rounds, good enough to beat the Delaware’s score of the previous night.

Practice and refinement of the skills of loading, siting, and firing the guns proved that the North Dakota’s big guns could fire 3 rounds per minute. Altogether, her ten 12-inch guns could fire thirty rounds per minute.

the man behind him reports to other members

of the gunnery crew through a communications tube.

2002-P-15-Album1-087.

By 1915, the North Dakota could compete well in the fleet’s gunnery practice. During gunnery practice in January that year, the North Dakota hit 60.518 per cent of her shots – a grand improvement over the thirty percent originally expected of the this type of ship, and a massive improvement over the two to threes per cent success rate of the Navy in the Spanish American War.

Practice on the big guns of the dreadnoughts such as the North Dakota brought about a spirit of teamwork in the floating community. One reporter who was present when the big guns were fired wrote:

There is a community of interest between the officers and men. The reasons for every order are fully explained, so that the men are thoroughly familiar with the object sought and with the material used. This applies not only to loading and firing the guns but to the whole fire-control and range-finding system, so that when a naval battle is fought, intelligent petty officers may take the place of officers who are killed or disabled. The whole service is working together with one end in view, that of efficiency in battles.

Sources: Scientific American, 11 November and 9 December, 191; New York Times, 31

site – or aim – the big guns with remarkable accuracy. 2002-P-15-Album1-034 #3.

Activities

- Reading the Evidence: Download worksheet below

Choose one photograph of life on the North Dakota. Divide it into quarters and make lists of objects, people, and activities in each quarter. Does your list answer some questions about life on the ship? Does your list raise more questions about life on the ship? Write down your questions. Use this form to make your lists.

- Debating the Evidence:

Discuss the schools held on the ship for the enlisted men. Some of the questions that you might discuss are:- Were the lessons valuable to the men, or were they a waste of time?

- Could anyone really make educational progress while studying only one hour and fifteen minutes a day?

- Would education make better sailors (seamen), or would the enlisted men (seamen) want to get off the ship and get a better job before their enlistment was up?

- Were the officers enthusiastic about educating the seamen?

If people in your class hold different views on the education of enlisted men, you can have a debate. You must gather your evidence or facts, and develop a strong position or argument to defend your side of the debate. Debate the resolution by having one group take the affirmative (or accept the resolution) and another group take the negative (or disagree with the resolution):

Resolved: Taking time for education aboard the USS North Dakota was beneficial to the officers and enlisted men of the ship.

- Analyzing the evidence:

Historians interpret facts to explain the importance of events in the past. Two events on the North Dakota need more analysis. Spend some time thinking about one or both of these events and try to provide an explanation.- Crossing the Line celebration. Why is this celebration so important that ships’ crews have done this for centuries? What is the meaning of the costumed characters such as Davy Jones and King Neptune?

- The fire on September 8, 1910. Three men died, six men were honored as heroes. The new ship was disabled. Why was this event an important news story in 1910? Is it just as important today?

- Debating the Evidence:

Discuss the schools held on the ship for the enlisted men. Some of the questions that you might discuss are:

- Were the lessons valuable to the men, or were they a waste of time?

- Could anyone really make educational progress while studying only one hour and fifteen minutes a day?

- Would education make better sailors (seamen), or would the enlisted men (seamen) want to get off the ship and get a better job before their enlistment was up?

- Were the officers enthusiastic about educating the seamen?

If people in your class hold different views on the education of enlisted men, you can have a debate. You must gather your evidence or facts, and develop a strong position or argument to defend your side of the debate. Debate the resolution by having one group take the affirmative (or accept the resolution) and another group take the negative (or disagree with the resolution): Resolved: Taking time for education aboard the USS North Dakota was beneficial to the officers and enlisted men of the ship.

- Analyzing the evidence:

Historians interpret facts to explain the importance of events in the past. Two events on the North Dakota need more analysis. Spend some time thinking about one or both of these events and try to provide an explanation.

- Crossing the Line celebration. Why is this celebration so important that ships’ crews have done this for centuries? What is the meaning of the costumed characters such as Davy Jones and King Neptune?

- The fire on September 8, 1910. Three men died, six men were honored as heroes. The new ship was disabled. Why was this event an important news story in 1910? Is it just as important today?