While the post gardens were extremely important sources of nutrition for soldiers, they also served to provide evidence for the potential of the northern plains to support agriculture and farm families. The debate about the economic future of the plains emerged in early 1874 just as the Northern Pacific Railroad (NPRR) was beginning to fail financially and while its surveyors were attempting to locate the best route through northern Dakota Territory and Montana.

The debate began with two rather unlikely opponents—at least unlikely in the field of agriculture. General William B. Hazen commanded Fort Buford at the confluence of the Yellowstone and Missouri Rivers. His troops maintained gardens on the riverbank, which contributed to the improved health of the soldiers. However, Hazen argued that though the gardens could be maintained with the great effort of the soldiers and their ideal location on the river, general agriculture was bound for failure. Colonel George A. Custer also contended that the lands surrounding Fort Buford would never support general agriculture but were exceptionally fine grazing lands for cattle and horses. Other voices entered the debate too, including General Thomas Rosser, the engineer who supervised NPRR construction; and a correspondent sent to the region by the New York Times who reported negatively about the region.

While the famous and not-so-famous debated the future of agriculture in Dakota Territory, settlers in the Red River Valley and in the Bismarck region began planting wheat and other grains and turned to their own gardens to support their families. They also planted fruit trees and shrubs. By 1880, the debate about the quality of the region for agriculture had quietly died down. In the end, both Custer and Hazen were proven right: periodic drought characterized the climate of the west-river country, though small grains did fairly well, and cattle ranchers prospered. The Red River Valley became known as the “breadbasket of the world” for its highly productive wheat farms. The Northern Pacific Railroad eventually completed its line from Minneapolis through Dakota to Seattle in 1883.

General Hazen

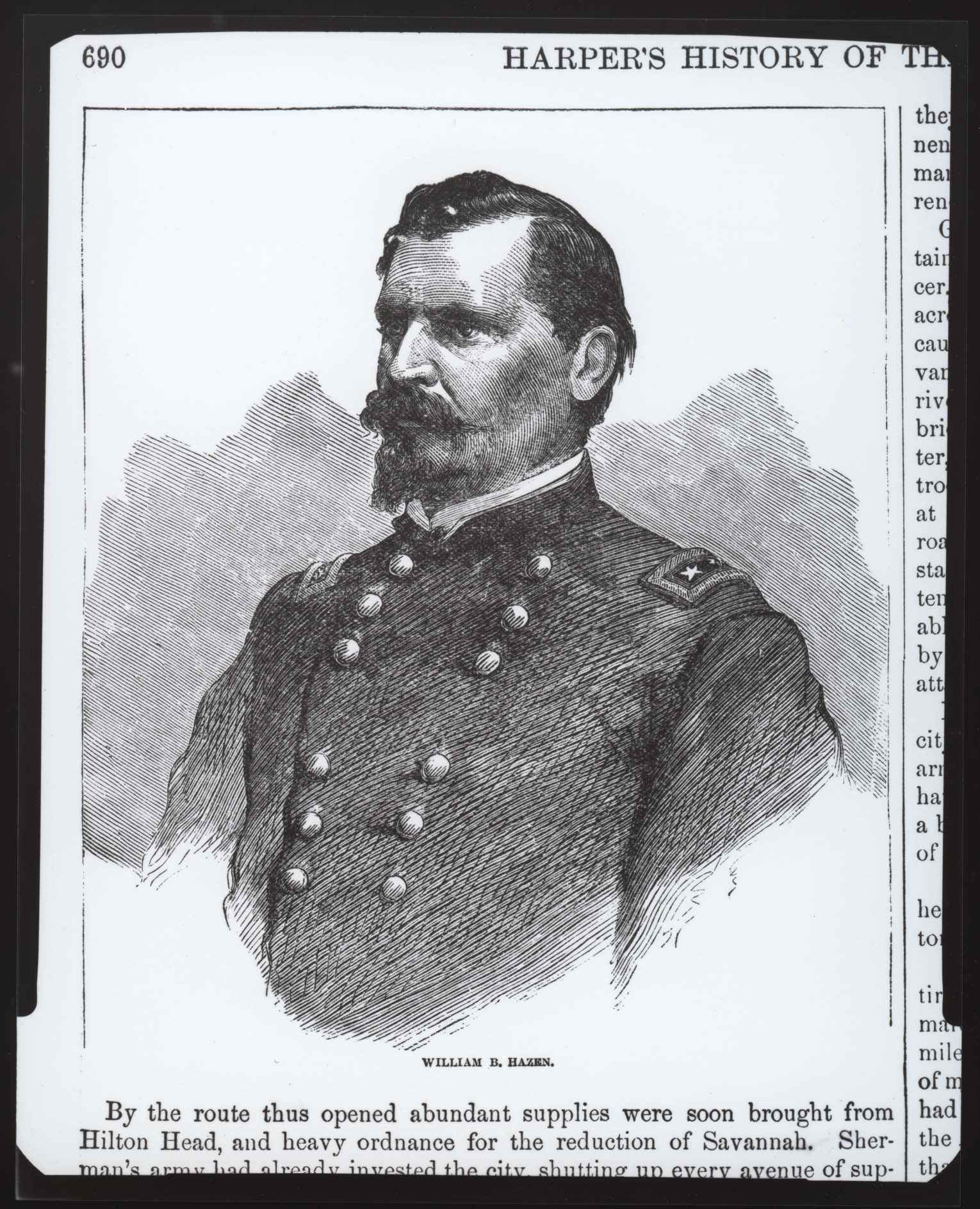

General William B. Hazen, commanding officer of Fort Buford, wrote letters and articles contending that the northern Great Plains would never support agriculture because of the lack of rainfall and the extreme temperature fluctuations. On February 7, 1874, the New York Tribune published a letter from Hazen (dated January 1, 1874), that was later published in a pamphlet titled Our Barren Lands. A longer article, titled “The Great Middle Region of the United States,” was published in the North American Review in 1875.

In his letter to the New York Tribune, Hazen noted that during the summer of 1873—an exceptionally rainy season—the post garden located on the river bank about two feet above the high water level, produced “potatoes, native corn, cabbage, early–sown turnips, early peas, early beans, beets, carrots, parsnips, salsify, cucumbers, lettuce, radishes and asparagus.” On the other hand, melons, pumpkins and squashes in the post garden did not mature, and tomatoes did not ripen.

Hazen’s comments were published shortly before the Northern Pacific Railroad, then building into northern Dakota Territory, declared bankruptcy. The success of the railroad depended on the appeal of the territory through which it built its line. Hazen believed that farmers who purchased land from the railroad, or claimed a quarter section of land under the Homestead Act, would find that they could not raise a crop every year because of the lack of rainfall, heat, and early frost. The “northern tropical belt” he refers to was the term applied to a region that included Dakota Territory and southern Saskatchewan by writers who stated that the northern Great Plains had “an atmospheric river of heat” that kept the region warm through the Fall.

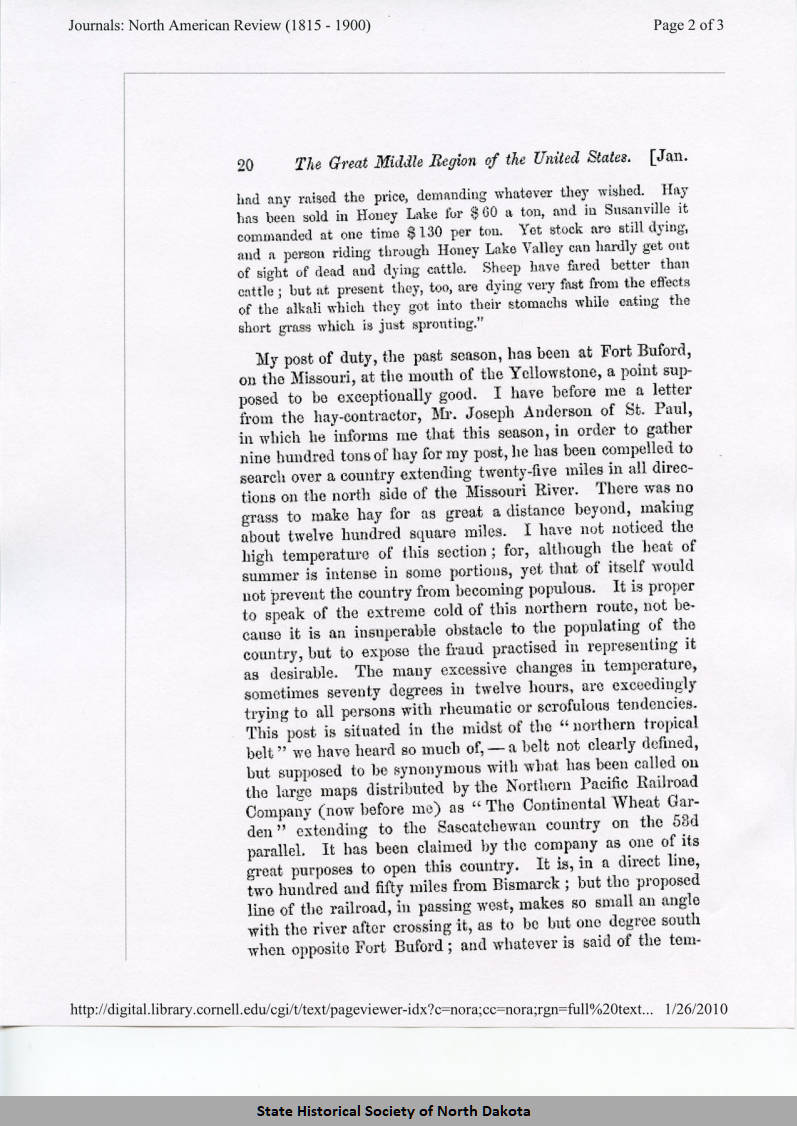

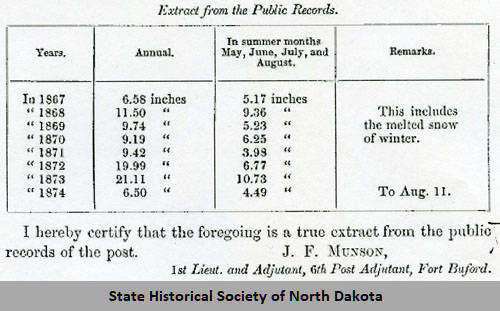

and a chart of the rainfall records from Fort Buford: [see Featured Sources U and V]

| Source S |

William B. Hazen served at many frontier Army posts. He was commanding officer at Fort Buford from 1872 to 1876. He wrote that his experience in the West led him to believe that farmers could not succeed in Dakota. SHSND A5103. |

| Source T |

Excerpt from Hazen’s Article:

http://www.digitalhorizonsonline.org/digital/collection/uw-ndshs/id/5124/ |

| Source U |

Temperature Chart

http://www.digitalhorizonsonline.org/digital/collection/uw-ndshs/id/5124/ |

| Source V |

Rainfall Chart

http://www.digitalhorizonsonline.org/digital/collection/uw-ndshs/id/5128 |

New York Times

A reporter for the New York Times newspaper traveled up the Missouri in the early spring of 1874. Hazen’s article had already appeared in the New York Tribune and Custer’s response would appear soon in the Minneapolis Tribune. On April 5, the correspondent, who traveled by sleigh on the banks of the still-frozen river commented on the area near Fort Buford. His article appeared in the Times on May 17, 1874.

“...we reach Fort Buford....The only timber sufficiently large for the sawmill is the cottonwood which makes very inferior lumber or building material. There is some red cedar, elm, and ash, but spare in quantity and poor in quality….At the confluence of the Yellowstone River with the Missouri, and on the north bank of the latter, Fort Buford is located....The winter here has at least the merit of duration, and is not yet over. Neither the Yellowstone or the Missouri Rivers is yet free of ice, and boats are not expected up until the early part of May....The thermometer at this post, according to the official register, marked 22 [degrees] below zero on the 10th of March. The climate is very healthy for those inured to it. The post is garrisoned by six companies of infantry, commanded by Major Gen. Hazen....This will probably be long occupied as a military post, since the surrounding country offers no inducements to settlers....”

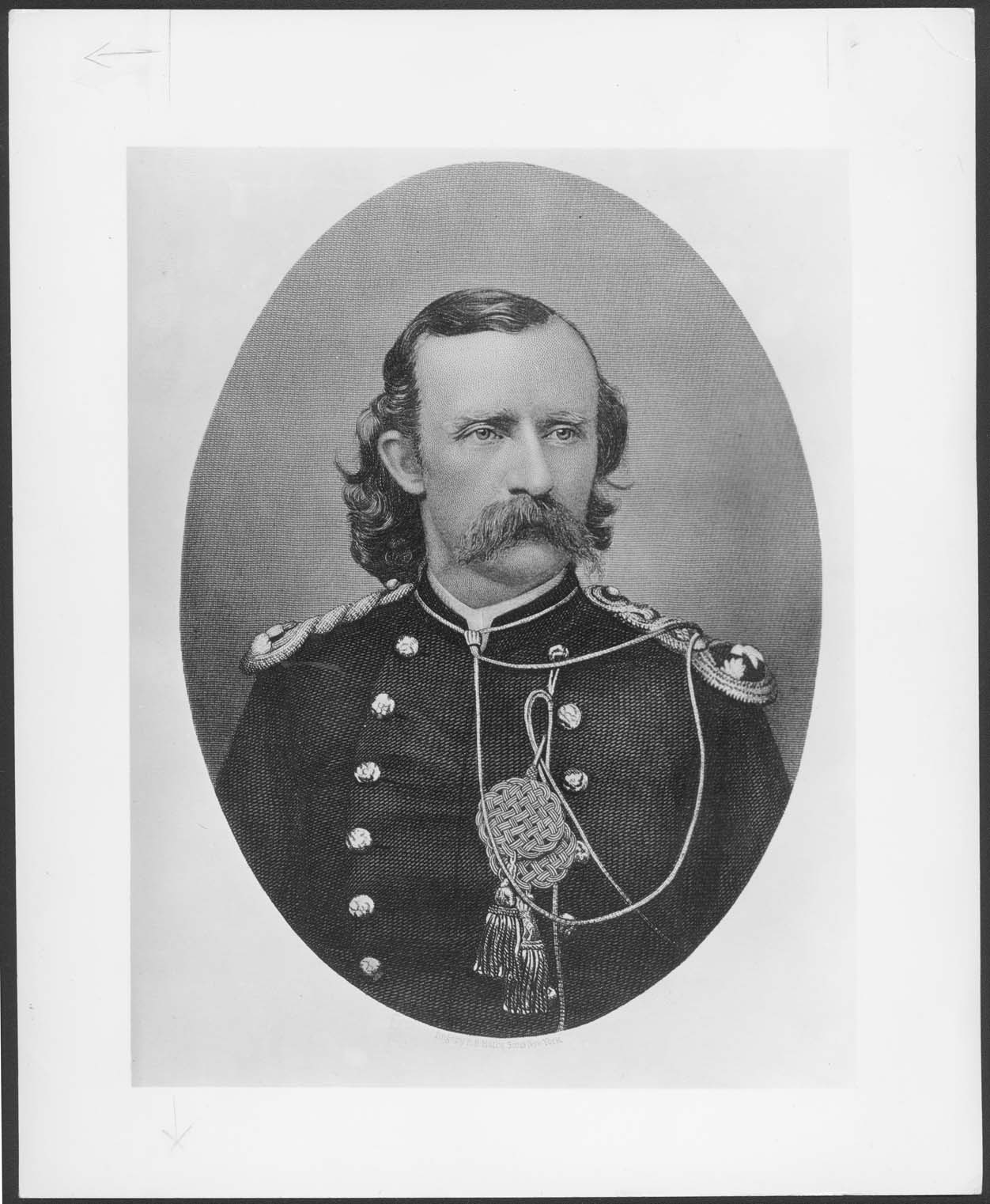

Colonel Custer

George Armstrong Custer took command of Fort Abraham Lincoln in 1873. From this post, he accompanied engineers of the Northern Pacific Railroad on their surveying expeditions to the Yellowstone River, explored the Black Hills, and ultimately marched his command to the deadly battle at the Little Big Horn River. Custer opposed Hazen’s views on the agricultural potential of the northern Great Plains. Though his experience on the northern plains was not as extensive as Hazen’s, and Fort Abraham Lincoln was a relatively new post which did not have 8 years of records like Fort Buford did, he made strong arguments about why Hazen was wrong and gave a very positive view of the future of Dakota. He presented notes from the Yellowstone Expedition of 1873 (from Fort Abraham Lincoln to western Montana), and asserted his personal experience on an Indiana farm in his youth. Custer sent his letter to the Minneapolis Tribune which published the letter on April 17, 1874. Here are excerpts from that letter:

“...The agricultural lands which are peculiarly valuable as such are to be found east of the Missouri River, while the lands west of the Missouri are regarded as being valuable for purposes of grazing, and as a mineral region....My diary [of the Yellowstone expedition] shows that my command encamped every night, with a single exception, where wood, water and grass were to be had. The horses of my command [more than 3000 animals] were put out to graze every evening, their allowance of grain in consequence being reduced to less than one-third. The beef cattle subsisted entirely upon the grazing obtained by them after the arriving in camp in the evening. And their condition was good....

For upwards of a hundred and fifty miles, after leaving the Missouri, we marched day after day over a beautiful and rolling country, by a route, which, under ordinary circumstances, would be entirely practicable for a lady’s [carriage]. Up to the dividing line, which is as distinctly marked as the opening furrow through a beautiful meadow, we rode without obstacle to where at our very feet, spread out before us, lay the wonderful awe-inspiring “Bad Lands” which, at first glance seemed impassable to man or beast. Yet we found a route for our immense wagon train to pass through without scarcely displacing a shovelfull of earth except in repeated crossings of a water-course....

I have seen...at a great many points both in the “Bad Lands” of the Little Missouri and in those of the Yellowstone, the exposed veins of coal which future development could and will render of incalculable value to the adjacent country....

...I will make one statement which can be applied generally to the country between the Missouri and Yellowstone rivers, along the route of the Northern Pacific Railroad, embracing about 225 miles of territory. From this I will deduct the two narrow strips of “Bad Lands,” the “exceptional waste tracts” running up and down the valley of the Little Missouri and the east side of the valley of the Yellowstone—in all say a belt twenty-five miles wide—deduct this, which as I have before stated, will never be valuable or fit for agricultural purposes; and the residue, taken as a immense area, constitutes as fine a grazing region as I have ever seen. We occupied but one camp which did not possess the three requisites of wood, water, and grass in sufficient quantities.”

Custer cited a letter written to him by Brevet Major General W. P. Carlin who was in command at Fort Abraham Lincoln during the Yellowstone Expedition. Carlin wrote to Custer

“We broke up eight acres for our garden in May, 1873, it was the first breaking. It was harrowed for the purpose of tearing the sod, and planted partly in May and partly in June. Last spring was considered a very late one—from two weeks to a month later than usual. We planted potatoes, turnips, carrots, beets, cabbages, squashes, cucumber, water melons, muskmelons, radishes, lettuce, onions, beans, peas, tomatoes, egg plant and Minnesota early corn. The corn matured and was consumed long before frost. Some of the water melons ripened before frost though not of an early kind. The troops had all of the vegetables they could use until about the 21st of September when the garden was taken by the troops and teamsters of the Yellowstone expedition. I never saw a more luxuriant growth of vegetables than we had in the garden last year. If it had been broken the year before and planted early and some care had been taken to protect the melon and tomato vines with boxes, the top of which should have had and abundance of melons and tomatoes. No irrigation was required here last year. Rains were frequent and copious. As you are aware the garden was on the bench about thirty feet above the river. The old post where the infantry are now stationed is about two hundred and ninety feet above the river. On this high point I sowed a strip of oats about two feet wide, two hundred feet in length. The oats grew to about thirty inches in height, though thickly sown and matured early. Better oats could not be found.”

Custer continued:

“...General Hazen has attempted to convey the impression to the uninformed reader that he writes from and of a point on the Northern Pacific Railroad and within its land grant when in fact he was at least 120 miles north of the located line and 200 miles west of the westernmost acre owned by the railroad company. He implies and endeavors to make his readers understand that the Northern Pacific Railroad Company is endeavoring to build a railroad through the region adjacent to Fort Buford, and that the company is trying to convince the public that said region is unfit for agriculture, when the facts are that the Company thoroughly examined this Buford region, rejected it as unfit for its purpose, and has never...wished to convey the impression, that this region is desirable for agriculture, or anything else.”

| Source W |

Colonel George Armstrong Custer was a well-known Army officer of both the Civil War and the western frontier. He opposed General Hazen’s views on the poor agricultural promise of the Missouri River country. SHSND 75-245. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source X |

Temperature Chart

|