General Philippe Regis de Trobriand

General Philippe Regis de Trobriand came to Fort Stevenson in 1867. His troops built the post, barely completing the necessary buildings before the extremely harsh and early winter began. Trobriand’s diary offers us a look at a wintertime diet and helps us understand why scurvy and other dietary diseases (such as dysentery) were problems for enlisted men but not officers. Officers had better food, made enough money to purchase extra or better-quality food at the nearby trading post, and usually had a cook to prepare meals as well.

By March 1868, Trobriand was beginning to worry about scurvy among the troops. His figures (April 8, 1868 entry) indicate that the command might have some difficulty in putting a fighting force into the field if necessary due to the number of sick soldiers. He looked for the arrival of the first steamboat, but before that soldiers gathered wild onions to improve the quality of their diets. Because of the work of construction at Fort Stevenson during the summer of 1867, soldiers did not plant a garden. The next summer they planted one, but Trobriand feared that grasshoppers would destroy it and leave the soldiers once again subject to the vitamin deficiency disease.

Trobriand and his officers learned a great deal about the course of the disease during that hard winter of 1868 when a total of 79 soldiers suffered from scurvy. Trobriand prepared the post to prevent scurvy the next winter by laying in supplies of pickles, sauerkraut, and vinegar. Pickled vegetables were probably sent upriver in barrels, saving space and weight over canned foods. The pickling brine would also help prevent freezing in the inadequately heated storehouses. The plan succeeded—during the winter of 1869, only 5 soldiers came down with scurvy.

Trobriand’s diary was published as Military Life in Dakota: the journal of Philippe Regis de Trobriand, translated and edited by Lucille Kane (St. Paul: Alvord Memorial Commission, 1951).

| Source A |

This illustration from a 19th century medical book, shows the lesions caused by scurvy. Bleeding from the hair follicles usually started in the legs, demonstrating the weakness of the blood vessels due to a lack of Vitamin C. from Prince A. Morrow, A.M., M.D., Atlas of Skin and Venereal Diseases, (New York: William Wood & Co., 1889), Plate LV. http://www.digitalhorizonsonline.org/digital/collection/uw-ndshs/id/5116 |

Frontier Scout

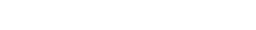

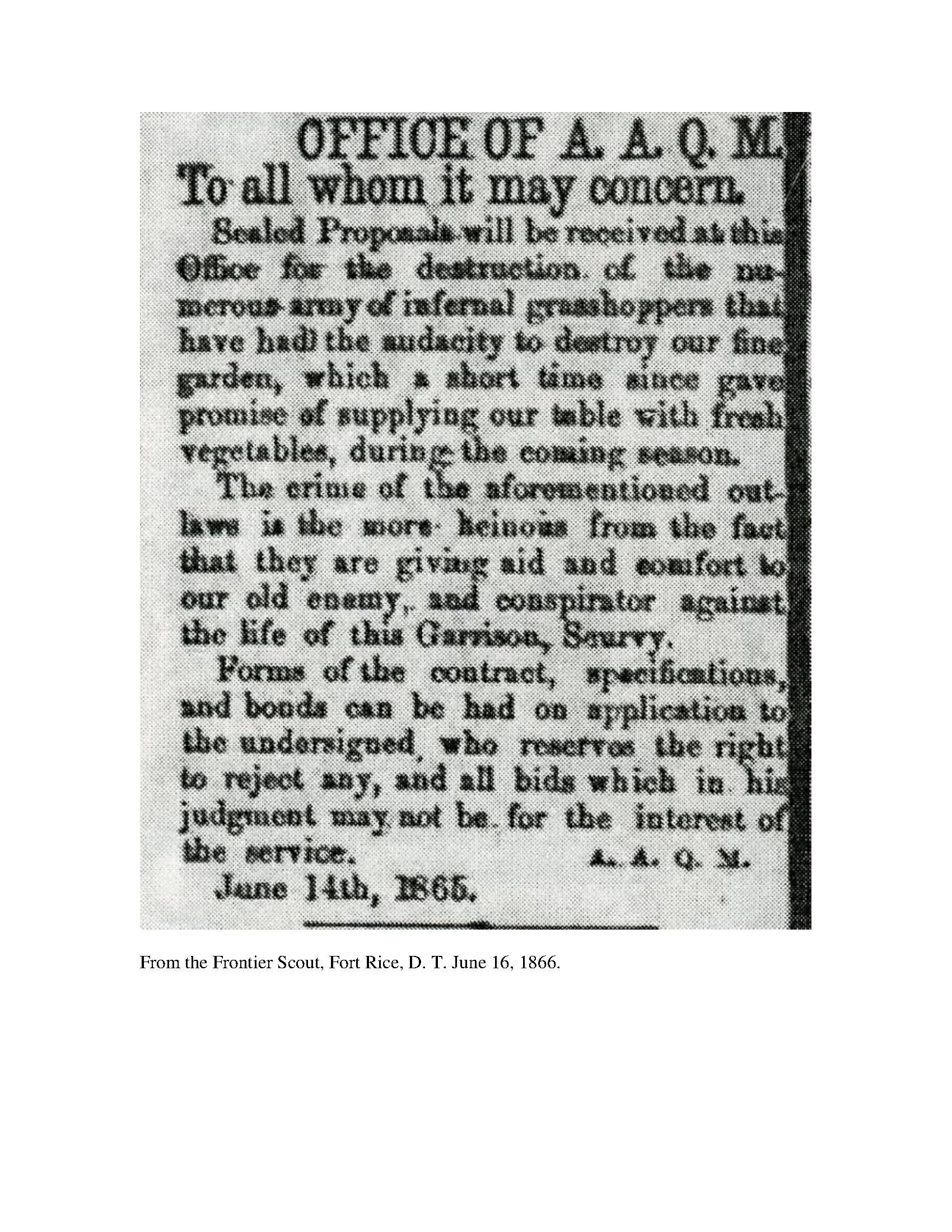

Fort Rice was established on the west bank of the Missouri River, in what is now Morton County, in 1864 by General Sully during his campaign against the Dakota and Lakota (Oceti Sakowin). Upstream, near the confluence of the Yellowstone with the Missouri River, soldiers also briefly occupied Fort Union. At Fort Union, Robert Winegar & Ira F.Goodwin began to publish a post newspaper, the Frontier Scout. When the command was transferred to Fort Rice, Capt. E. G. Adams and Lieutenant C. H. Champney took over publication of the newspaper.

The winter of 1864–1865 was hard on the soldiers at Fort Rice. No railroad had yet reached Dakota Territory. The river had frozen and no steamboats would come until May. Overland transportation was limited to what dogsleds could carry. The usual military diet of foods that could be easily stored and prepared at remote posts was the only source of food available to enlisted men. Rations for soldiers generally consisted of salt beef, salt pork or bacon, hardtack biscuits, bread, and baked beans. As a result of this poor diet and the long winter isolation of the post, scurvy and other dietary diseases took a heavy toll on the command. Late in the spring, the Frontier Scout printed the names of the men who had died over the past Fall and Winter. By March, scurvy was the leading cause of death, and in April, it was the only cause of death listed.

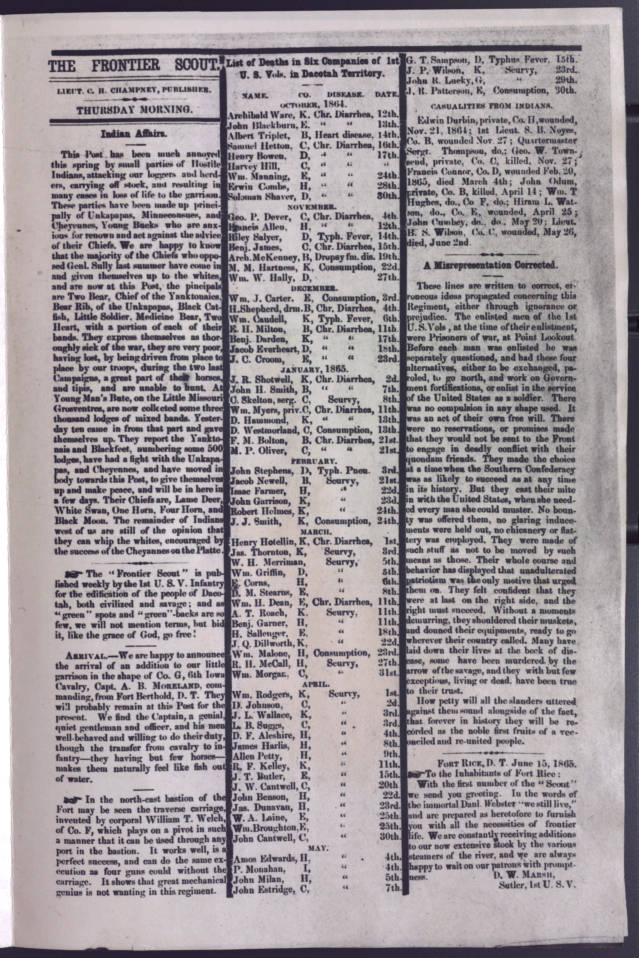

During the summer of 1865, the soldiers at Fort Rice worked in a post garden. As early as 1818, the War Department ordered remote posts where the Quartermaster was unable to purchase locally grown fresh vegetables for the soldiers’ meals, to raise their own vegetables. However, as the frontier moved west into areas where water was scarce and north where winter cold made for short growing seasons and difficulties in long-term storage, the post gardens did not produce enough to maintain the soldiers’ health. The other problem was grasshoppers, the scourge of the Great Plains. The June 15, 1865 edition of the Frontier Scout called for “Sealed Proposals” for a plan to combat grasshoppers (See Featured Source D). Though the notice is written in jest, the problem was a serious one. Grasshoppers could destroy the post garden in a matter of days, leaving the soldiers once again dependent on supplies that could come only by steamboat. Good weather, and local, wild vegetables supplementing the supplies arriving by steamboat in early May brought recovery to those soldiers still fighting scurvy. On June 22, 1865, the Scout reported that wild onions had greatly improved the health of the post, even though the potatoes brought by steamboat were nearly unfit to eat.

Fort Rice had one of the worst outbreaks of scurvy, but Fort Stevenson also had a bad scurvy season a few years later and other posts had occasional cases of scurvy. By 1870, most Dakota posts had managed to raise vegetables, and many had built underground storehouses where potatoes, onions, and other vegetables could be safely kept over the winter.

| Source B |

The original buildings of Fort Rice housed “Galvanized Yankees” during the winter of 1864–1865 when scurvy took many lives and left many more incapacitated. Galvanized Yankee was a term used to describe confederate soldiers of the Civil War who, as prisoners of war, either volunteered or were conscripted into the Union army and subsequently sent to the frontier areas of the Great Plains. SHSND B0329-00001. |

| Source C |

Frontier Scout Volume 1, Issue 1

You can read all the issues of the Frontier Scout online at http://history.nd.gov/archives/frontierscout.html. |

| Source D |

The June 15, 1865 edition of the Frontier Scout called for “Sealed Proposals” for a plan to combat grasshoppers. http://www.digitalhorizonsonline.org/digital/collection/uw-ndshs/id/5217 |

| Source E |

Frontier Scout: Sanitary Transcription

This excerpt on sanitary conditions at Fort Rice, Dakota Territory is from Frontier Scout volume 1, number 2 (June 22, 1865): We are happy to state that the Sanitary condition of the post is very much improved. The number on the sick-list having decreased rapidly since the appearance of wild onions, and the arrival of a few potatoes. A few weeks since there were fifty serious cases of scurvy in the Post Hospital, now there are only eleven and those convalescent. The strictest rules for the health of the troops, such as cleanliness of persons and quarters, proper cooking of food, etc., are still enforced, and we hope soon that a messenger of mercy, in the form of a steamboat may arrive bringing us a large supply of vegetables. The potatoes, which came by the “Fanny Ogden” are nearly all in a state of decomposition and will be of but little service to us. It is useless to attempt to send potatoes to this country in sacks at this season of the year. We trust that during the season the requisition, which have been made for anti-scorbutics will all be filled and forwarded in good condition, so that whoever may be so unfortunate as to be exiled here the coming winter may not suffer as we have for want of healthy diet. We are like a man in a well, dependent on those at the top for sustenance. If our pleadings are not responded to from down the river, and the means of self- preservation furnished, we must die. From what we hear, however, we feel encouraged to believe that our wants will be supplied. During the past winter we have suffered severely, more probably than a regiment of northern men would have suffered, the soldiers stationed here being southerners, enlisted prisoner of war, who have seen from two to three years of active service on southern fields and until last fall never saw cold weather, and we believe it was unfortunate for them to be sent here just as the cold season was commencing. Medicus http://www.digitalhorizonsonline.org/digital/collection/uw-ndshs/id/5138 |

Martha Gray Wales

Martha Wales (née Gray) was a small girl in 1867 when she lived at Forts Buford and Stevenson. Her father, Charles C. Gray, was a military surgeon, or physician, who was responsible for the health of the soldiers stationed at the fort, then under command of General Regis de Trobriand. In her memoir, Wales described the difficulty of keeping enlisted men supplied with vegetables and fruits necessary for preventing diseases, the most prominent of which was scurvy:

“Our men had been suffering from scurvy in increasing numbers. The officers managed better as they had private stocks of canned goods. Game was plentiful for the shooting, and the government tried to maintain herds of beef cattle, but these were sometimes shot by Indians and a good deal of the meat for the enlisted men was necessarily salted. My father remembering that old Fort Berthold had been established by a Frenchman years ago, that where a Frenchman had lived, there must be a kitchen garden and so given a guard he started out as early as the frost was out of the ground to see what he could find. To his delight there were wild onions and Jerusalem artichokes which greatly helped the men’s diet with the canned goods and fresh vegetables which came to the Post by steam boat.”

Source: Mrs. G. W. (Martha) Wales. Page 9, Memoir written for State Historical Society of North Dakota, MSS 20046. See also: “When I was a Little Girl: Things I Remember from Living at Frontier Military Posts” by Martha Gray Wales, ed by Willard B. Pope in North Dakota History vol 50, No. 2 (Spring 1983): 12–22.

| Source F |

Officers’ quarters at Fort Buford after a winter storm. Winters could be very severe and long lasting on the northern Great Plains. The isolation of army posts during the winter meant that vegetables were scarce, leading to an increased incidence of scurvy. SHSND 2019-P-029-00004. |

General Philippe Regis de Trobriand

General Philippe Regis de Trobriand came to Fort Stevenson in 1867. His troops built the post, barely completing the necessary buildings before the extremely harsh and early winter began. Trobriand’s diary offers us a look at a wintertime diet and helps us understand why scurvy and other dietary diseases (such as dysentery) were problems for enlisted men but not officers. Officers had better food, made enough money to purchase extra or better-quality food at the nearby trading post, and usually had a cook to prepare meals as well.

By March 1868, Trobriand was beginning to worry about scurvy among the troops. His figures (April 8, 1868 entry) indicate that the command might have some difficulty in putting a fighting force into the field if necessary due to the number of sick soldiers. He looked for the arrival of the first steamboat, but before that soldiers gathered wild onions to improve the quality of their diets. Because of the work of construction at Fort Stevenson during the summer of 1867, soldiers did not plant a garden. The next summer they planted one, but Trobriand feared that grasshoppers would destroy it and leave the soldiers once again subject to the vitamin deficiency disease.

Trobriand and his officers learned a great deal about the course of the disease during that hard winter of 1868 when a total of 79 soldiers suffered from scurvy. Trobriand prepared the post to prevent scurvy the next winter by laying in supplies of pickles, sauerkraut, and vinegar. Pickled vegetables were probably sent upriver in barrels, saving space and weight over canned foods. The pickling brine would also help prevent freezing in the inadequately heated storehouses. The plan succeeded—during the winter of 1869, only 5 soldiers came down with scurvy.

Trobriand’s diary was published as Military Life in Dakota: the journal of Philippe Regis de Trobriand, translated and edited by Lucille Kane (St. Paul: Alvord Memorial Commission, 1951).

| Source G |

Trobriand Diary Excerpts from the Diary of General Regis De Trobriand at Fort Stevenson: January 6, 1868 January 7, 1868 January 8, 1868 February 11, 1868 March 1, 1868 April 8, 1868 These regrettable health conditions are the result of being without fresh vegetables for a long time and of having rations of fresh meat distributed only twice a week. The principal food of the men is salt pork, salt fish; and so there is sickness. Nevertheless, it may be presumed that it would not have reached the proportions I have just indicated if our men had had good quarters from the beginning of winter. Unfortunately the work was begun too late last summer, and as I have related, one of the two companies was not comfortably installed until the last days of December, and the other in the first days of January. Until then they were exposed to the rough weather of the end of November and the whole month of December, with no shelter but miserable edge tents. When the snow and ice came, they dug out the inside of the quarters three or four feet deep, and built themselves small earthen fireplaces, which had the inconvenience of producing stifling heat when the fire blazed and freezing cold when it was out. Moreover, sleeping on the ground wasn’t good for them. Add to this and to the salt rations the constant fatigue from the hardest type of daily work, and it is not wonder that scurvy has been so prevalent, with upset stomachs, tired limbs, and sorely taxed constitution. Fortunately the ordeal is just about over, thanks to the imminent arrival of the steamboats and the supplies they will bring us. To combat this evil, and especially to forestall it, we have in addition to the usual remedies of the pharmacy, a small, wild white onion, or shallot, tasting very much like garlic, which grows in abundance on the prairie. The Indians gather much of it for us in exchange for small quantities of biscuits, and so the monotony of the usual fare is agreeably and usefully varied by this natural condiment, of which we are all very fond. The Indians supply us with a cylindrical tuber as thick as a thumb, which the Canadians call artichoke, I do not know why, for nothing is less like an artichoke. In form it is more like salsify. Raw, it is almost without flavor; cooked it tastes like a parsnip or like the most insipid turnip [this is probably the wild prairie turnip]. The wild shallot is infinitely preferable.... April 22, 1868 April 25, 1868 April 26, 1868 July 20, 1868 At this time, a black storm began to come up on the horizon to the north. Heavy clouds mounted one on the other, lighted by brilliant and repeated flashes of lightning, which were followed by rolling thunder, nearer and nearer. The noise of the grasshoppers seemed to be its feeble echo. When the storm came up almost above our heads, blasts of violent wind began to blow in squalls, sweeping everything before them, and great flashes of lightning rent the air. Then all that winged dust which was making the sky white passed over us rapidly. Carried by the storm, it crossed the Missouri, and scattered far out on the plains. Our gardens and pastures were saved, at least this time. The storm, before reaching its zenith, went east, and swept around far toward the south, where it finally disappeared, without moistening the soil of Fort Stevenson by a drop of rain, although it fell in torrents in other places. Great blasts of wind, fierce bolts of lightning, one of which killed an Indian mule grazing on the prairie; finally, a great roar of thunder; all the storm did for us was to drive away the grasshoppers, but it did not water our vegetables. July 21, 1868 March 9, 1869 |

Surgeon Reports

Starting January 1, 1869, Army surgeons (physicians, also known as Assistant Surgeon or Acting Assistant Surgeon) received a large blank book titled “Record of the Medical History of the Post.” Twice a year, the surgeon was to complete the record of sanitation and health at each Army post. The following selections from these documents contain some of the entries from each Army post in Dakota Territory for 1870 and 1874. The compiler of the reports indicated that in general the death rate (mortality) of soldiers was lower than “in previous years, but higher than that of civilian men of the same ages.” (Circular No. 4, p. xxxii) So, it appeared that while efforts to improve the diet and living conditions at military posts had been successful, the life expectancy of soldiers was still compromised by poor health. Each surgeon also reported on the size and history of the post, the square feet of space per soldier in the barracks and the quality of light and air. They also reported on the ability of the surrounding area to support agriculture and about the quality of the soil and the kinds of plants and animals in the area.

The selected quotations from these two sets of reports suggest that Dakota is a healthy place to live, that scurvy had become a less significant health problem, and that post gardens were cultivated with some success. The surgeons were also interested in how Native Americans managed to avoid scurvy, though the military understood little about the storage systems they used for dried vegetables and for pemmican which preserved fruit and meat in animal fat. The surgeon’s reports were an important resource for determining not only the health of the command, but whether settlers would be able to live and farm successfully in the region. The surgeons generally reported good soil and an abundance of wild fruit, but grasshoppers and inadequate rainfall were constant problems.

Sources:

Circular No. 4: Report on Barracks and Hospitals with Descriptions of Military Posts [1870] by John S. Billings, Assistant Surgeon, United States Army (New York: Sol Lewis, 1974).

Circular No. 8: Hygiene of the United States Army with Descriptions of Military Posts [1874] by John S. Billings, Assistant Surgeon, U.S.A.

Circular No. 9 Report to the Surgeon General on the Transport of Sick and Wounded by Pack Animals by George A. Otis, Assistant Surgeon, U.S. A. (New York: Sol Lewis, 1974)

| Source H |

1870 “When a man enlists as a soldier it is with the understanding, expressed or implied, that as his food, clothing, and dwelling place are to be regulated by others, they shall be selected, so far as possible, with reference to his health and comfort.” p. xxxii. Department of Dakota Fort Abercrombie: Assistant Surgeon W. H. Gardner. [The post has experienced a] “remarkable immunity from disease.... Scurvy has prevailed to some extent, owing to a want of care in providing the troops here with sufficient vegetable diet.... The Indians about here use in their diet a tuber like the artichoke, called Indian turnip, wild plums, and also cranberries and gooseberries, in the seasons when they are ripe, but these fruits are inconstant, and make but a small portion of their diet.” p. 376. 1868: scurvy cases 1 1869: scurvy cases 0 Fort Wadsworth: Report of Assistant Surgeon B. Knickerbocker. “The gardens are three in number, and distant over a half mile from the post. That belonging to the hospital contains a little over seven acres, which was under cultivation last season. The officers’ garden is located east from the post, and embraces about two acres. The company garden yielded last year 350 bushes of potatoes.” p. 379. Ft. Ransom: Report of Assistant Surgeon C. E. Munn. “There are 8 acres of land at this post appropriated for garden purposes, each company cultivating about three acres, and the remainder giving gardens to the hospital and officers. Some potatoes have been raised, but the main crop of vegetables has been destroyed by grasshoppers, which come in clouds from the northwest, and in a few hours destroy the entire garden.” p. 382. Fort Totten: Report of Acting Assistant Surgeon J. F. Boughter. “Each company has a kitchen and mess-room in the rear of the barracks.... The route of supply is, at present, by the Missouri River to Fort Stevenson, thence by wagon road. The river route is cheaper... [but] not enough to pay the risk of loss on the river, together with the damage and wastage, which are great.... Twelve months’ supply is usually kept on hand at the post.” p. 384. 1869: scurvy cases 4 Fort Rice: Report of Assistant Surgeon Washington Matthews. “During the first years, scurvy was a formidable malady, destroying many lives, and otherwise seriously reducing the efficiency of the garrison; but since the commissary has been better supplied the disease has almost entirely disappeared.” p. 394. 1868: scurvy cases 3 1869: scurvy cases 2 Fort Stevenson: Report of Assistant Surgeon Washington Matthews. “Gen. Sully’s third northwestern Indian expedition arrived, on its return march, at Berthold, August 8, 1865, and here Gen. Sully issued an order directing the evacuation of Ft. Union at the mouth of the Yellowstone. The evacuation was completed on the 31srt of August and from this time until the establishment of Fort Buford, in 1866, Berthold was the most extreme garrison in the valley of the upper Missouri. The troops consequently suffered from scurvy. No death from disease is known to have ever occurred among any troops at Berthold. On the 14th of June 1867, the troops moved from Ft. Berthold to a point 17 miles further east, where a post at that time, designated as “New Fort Berthold,” was about to be established. Ft. Berthold was never owned by the Government, nor as far as I am able to learn was any rent ever paid for it. The use of it was given by the agent of the Northwest Fur Company, who erected offices, quarters, and warehouses for himself outside of the fort, which he occupied as long as the military remained. p. 395. During the summer of 1867, the Sioux made three raids on the camp in force, and one attack in a small party. The troops were compelled to labor very hard after the building of the post was commenced, and as their food was deficient in variety, and being lodged in tents during the severest weather, they suffered greatly in health. Acute dysentery was the first prevailing disease. This reached its height in September 1867, when there were some fifty five cases on the report, besides a number of mild attacks not recorded. After this scurvy prevailed. This reached its height in April 1868, during which month there were sixty-one cases reported among the enlisted men alone, besides some forty or fifty able to perform light or partial duty, whose names were not taken upon the sick-list. The scorbutic taint was, however, even more widespread than these number would seem to indicate. The men were prone to contract diseases, slow to recover, and little able to bear their hard labors and the rigors of the climate; frost-bites were common. The troops were not completely housed until January 3, 1868.” p. 396. “On the bottoms near the mouth of Douglas Creek, about three-quarters of a mile from the post, an irregularly shaped piece of ground, containing between four and five acres, was cultivated as a post garden. Irrigation by hand was practiced during the dry season. Peas, beans, and lettuce grew well; cabbages and potatoes, being later in season, were eaten up by the grasshoppers before maturity. There are no hospital nor officers’ gardens.” “Slight scorbutic symptoms have again manifested themselves this winter, but they are readily dispelled.” p. 399. 1868: scurvy cases 79 1869: scurvy cases 5 Fort Buford: Report by Assistant Surgeon J. P. Kimball. “Gardens are cultivated, producing lettuce, radishes, cucumbers, and green corn in sufficient amount to furnish a fair supply to the entire garrison during the season; also a limited amount of green peas, cabbages, turnips, and beets. Tomatoes have not done well, the season being too short. Potatoes have proved a failure during the last two years, producing nothing but tops. The corn raised is a variety cultivated by the Ree [Arikara] Indians, which comes quickly to maturity…Rations, procurable from the commissary, are of good quality and sufficient in quantity. During the fall of 1868, and the winter of 1868 – 69, after the supply of vegetables from the garden was exhausted, the following articles of food, in addition to the regular ration issued from the commissary department, in the quantities stated, were found effectual in preventing scurvy and maintaining the command in excellent health, viz; Per 100 rations, ten pounds of dried fruit and five gallons of krout [sic] or curried cabbage twice a week; one gallon of molasses, twenty-five pounds of corn meal, and two and one-half gallons of pickles once a week.” p. 403. 1868: Scurvy cases: 33 1869: no scurvy 1874 Department of Dakota: Fort Abercrombie: Surgeon W. H. Gardner, U.S.A. “Scurvy has prevailed to some extent, owing to a want of care in providing the troops here with sufficient vegetable diet.” p. 390. “During the past year the production of the ordinary culinary vegetables supplied the wants of the garrison and left a sufficient surplus for winter use. A large root-house was in course of construction at the date of the latest information.” p. 391. Fort Abraham Lincoln: Surgeon James F. Weeds, and Acting Assistant surgeon J. Frazer Boughter. “The cellars of [the infantry barracks] are small and not frost proof.” p. 393. Fort Buford: Assistant Surgeons J. P. Kimball and J. V. D. Middleton. “Under each commissary storehouse is a cellar for the storage of vegetables, etc. A good supply is kept on hand for issue and for sale to officers. In the fall of 1873, a supply of potatoes was received sufficient to last until the opening of navigation in the spring. In favorable years, the post garden affords a valuable accession to the supply of fresh vegetables.” p. 401. Fort Pembina: Assistant Surgeon Ezra Woodruff. “A plat of 8 acres in extent, lying southeast of the post, has been inclosed with a rail-fence and plowed for a post garden. This piece of ground, owing to unskillful management, has yet produced but little. A smaller tract has also been cultivated the principal products have been potatoes, onions, beets, carrots, parsnips, radishes, green peas, and beans. The supply has never been sufficient for the wants of the garrison. A hospital garden was to be commenced in 1874. There are no officers’ gardens. Summer vegetables can be procured in limited quantities from the settlers in the vicinty.” p. 416. Fort Rice: Assistant Surgeon J. W. Williams. “During the first years of occupancy, scurvy was a formidable malady, and destroyed many lives. The “scorbutic taint” has never been absent until this year, when the daily allotment of vegetables is set at one pound per man. The intimate relation of the vegetable allowance to the percentage of sick at this post is instructive. In 1871, daily allowance of fresh vegetables per man, 9 ounces; annual per cent of sick, 261. In 1872, daily allowance of fresh vegetables per man, 12 ounces; annual per cent of sick, 188. In 1873, daily allowance of fresh vegetables per man, 16 ounces; annual per cent of sick, 108.” p. 424. Fort Seward: Acting Assistant Surgeon E. W. Du Bose. “On the bottoms west of the James River, about one-fourth of the mile from the post, a piece of ground, containing about eight acres, has been inclosed for post and hospital gardens, The soil is good, and produces beets, beans, cabbages, corn, lettuce, onions, pease, parsnips, potatoes, and turnips.” p. 427. Fort Stevenson: Assistant Surgeon Washington Matthews. “For agricultural purposes only the lower lands seem to be available, but without irrigation none but the hardier vegetables will thrive. In most seasons, and when grasshoppers are not as abundant as usual, careful husbandry may be rewarded by fair produce. At Fort Berthold, and other point in this neighborhood, the Indians have raised on the bottoms of the river, without irrigation, corn, squashes, and beans, with varying success for probably more than a century.” p. 438. “On the bottoms, near the mouth of Douglas Creek, about three-quarters of a mile from the post, an irregularly shaped piece of ground, containing between four and five acres, is cultivated as a post garden. Irrigation by hand is practiced during the dry season. Pease, beans, and lettuce grow well. Potatoes and onions are produced in quantities sufficient to last the command the greater portion of the year; turnips, beets, cabbages, are raised in less quantities.... The hospital is supplied with vegetables from the post garden.” p. 440. Scurvy appeared rarely and only as a secondary disease to another. Fort Totten: Acting Assistant Surgeon James B. Ferguson. “Post gardens have been cultivated for the past three or four years. Potatoes and other roots crops grow well; also onions, pease, beans, cabbage, corn, etc.... The only apparent drawback to agriculture in this region, so far as observed, is the destruction caused by countless hordes of grasshoppers, which make their appearance about midsummer every two or three years, and destroy every green thing above ground.... “Butter, eggs, fresh vegetables, etc, for winter use, cannot be purchased here, and are usually procured from either Saint Paul or from some of the small towns on the railroad, as Fargo, etc. p. 448. |

Captain Grant Marsh

The Missouri River, treacherous and shifting, was the main lifeline for the remote Army posts. The boats were faster than overland transport and could carry heavy freight. If a boat was delayed or sunk in the river, the Army posts were deprived of mail, pay, and food. Captain Grant Marsh was one of the most respected and experienced steamboat captains of the Missouri River. He understood the importance of bringing the steamboats upriver to the Army posts. In the Fall of 1869, Captain Marsh was hired by the Northwestern Transportation Company to take winter supplies to Army posts on the Missouri. His boat was the North Alabama, a good, fast boat of 260 tons. He left Sioux City, Iowa on October 1 with a load of vegetables and other supplies for the winter, as well as the Army paymaster. It was late in the season for steamboats, but the weather was warm, and Marsh reached Forts Randall, Hale, Sully, Rice, and Stevenson where boatmen unloaded potatoes, turnips, onions, cabbages, and apples.

On October 17, the weather began to change. The temperature dropped; ice began to form on the river. Marsh was worried about the vegetables freezing before he could get to Fort Buford. To preserve them, he moved the potatoes from the deck to the hold where small wood fires kept the temperature above freezing. To prevent accidental burning of the entire boat, Captain Marsh ordered the fires guarded at all times. The vegetables did not freeze, but Marsh had other problems to face. Drift ice in the river prevented the boat from moving as swiftly as she could under better conditions. Twenty-five miles short of Fort Buford, the North Alabama became embedded in ice. Two Army Scouts of the Arikara nation were on board the steamboat. They were sent overland to Fort Buford to notify the commanding officer that the boat was nearby, stuck in ice, and that precious vegetables were on board. The next day, covered wagons from Buford arrived under mounted military guard. The vegetables (and the Army paymaster) were transported to Buford where they were safely stored for the winter.

Marsh expected that the North Alabama would stay in the ice for the entire winter, but a few days later, temperatures rose, and the boat moved into the current and returned to Sioux City. The North Alabama remained in service until October 27, 1870, when she struck a snag and sank in the river near the Nebraska shore. None of her crew drowned.

Source: Joseph Mills Hanson, The Conquest of the Missouri: being the story of the life and exploits of Captain Grant Marsh. Chicago: A. C. McClurg & Co. 1916 (3rd edition).

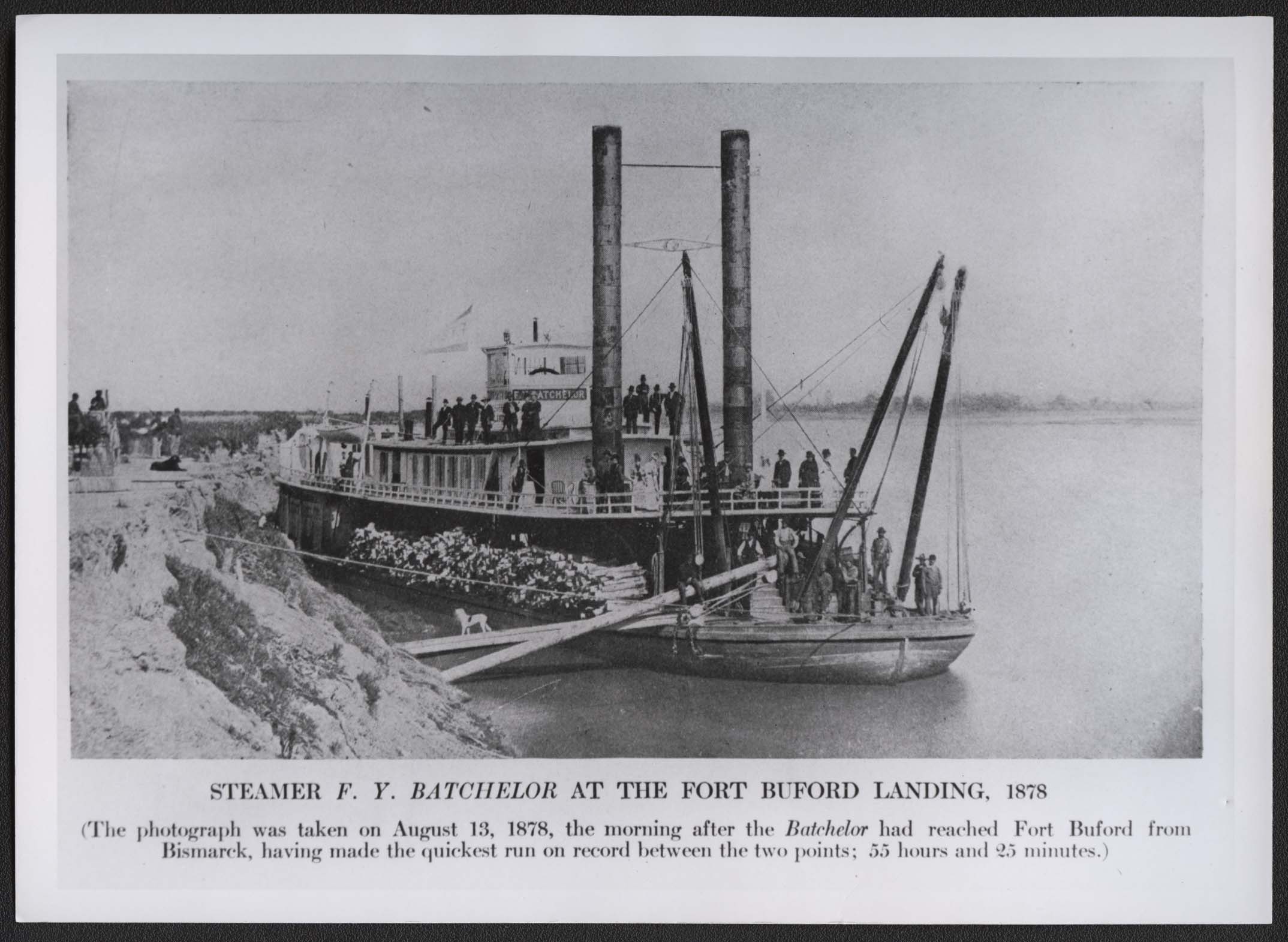

| Source I |

The steamboat Batchelor ties up at Fort Buford in 1878. Boats of this size brought passengers and supplies during the short navigation season on the Missouri River. A4234 |

Indian Gardens

Though soldiers and officers stationed at Army posts throughout the West often met and worked with Native Americans, these encounters did not always lead to understanding and the exchange of important information. Native Americans often faced food shortages during particularly long winters, or after dry and unproductive summers, but they seemed to have avoided scurvy during the years when the Army was becoming established on the northern Great Plains. Assistant Surgeon W. H. Gardner noted in his 1869 report from Fort Abercrombie that Native Americans did not have scurvy, and though he knew that they ate wild fruits, he could not understand how these fruits could be available in late winter in quantities sufficient to prevent disease.

What the Army surgeons did not understand was that Native Americans had long established foodways that minimized the risks of experiencing starvation and prevented vitamin deficiency diseases. In central Dakota, the Arikara, Mandan, and Hidatsa had gardened for centuries, raising corn, squash, and beans to supplement wild vegetables and bison meat. They dried the vegetables and stored them in underground caches for use in late winter.

Mobile tribes that followed seasonal rounds usually did not garden on the scale that village tribes did but relied more on gathering wild fruits and vegetables which they dried and stored or mixed with animal fat and dried meat to make pemmican. Pemmican contained nutrients and calories necessary for subsistence, and the fat served as a preservative. Horticultural, or gardening, tribes also traded surplus crops to migratory hunting tribes and occasionally supplied the Army with corn.

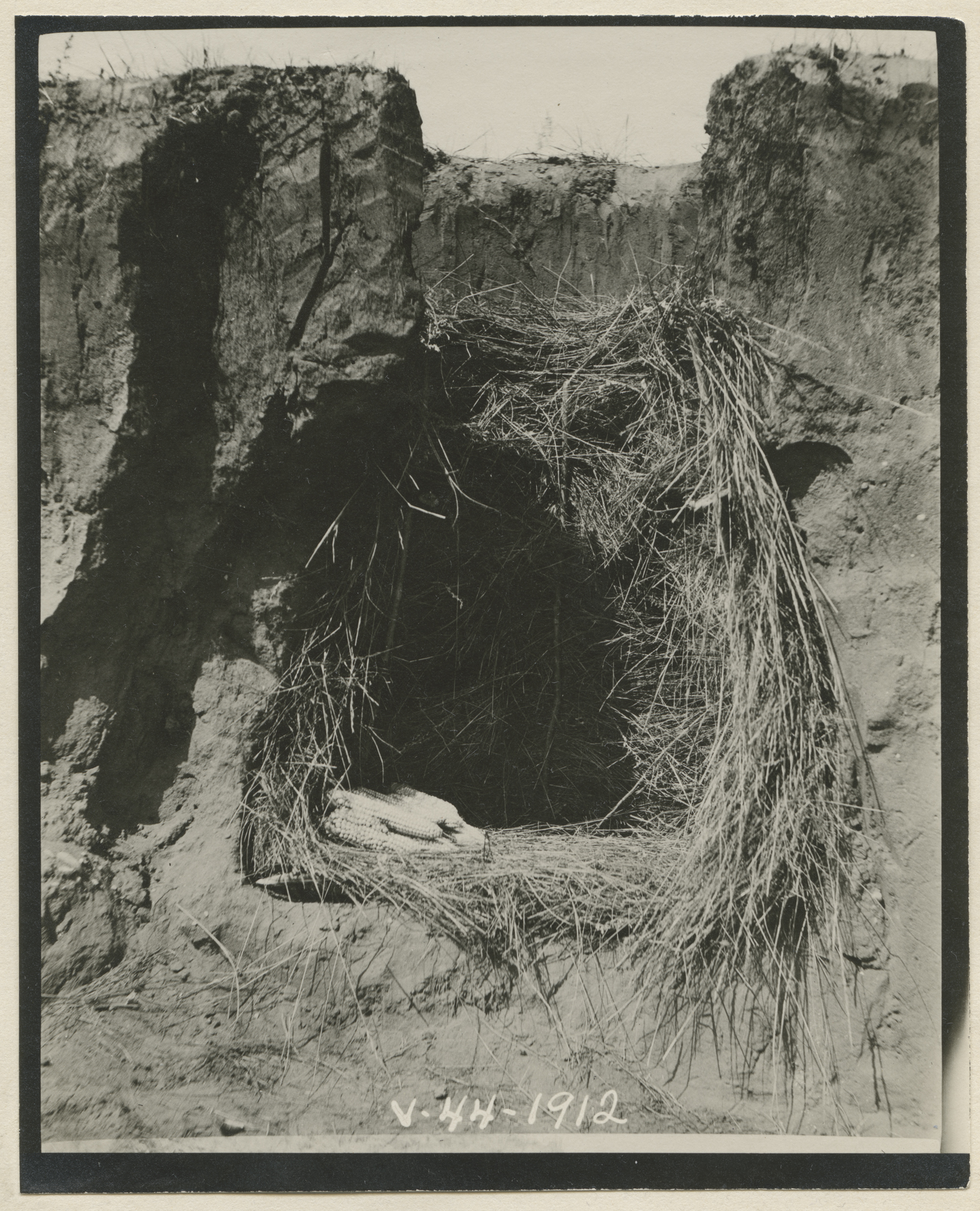

| Source J |

Surplus vegetables were stored in underground cache pits like this one constructed in 1912 by Buffalo Bird Woman. The grass lining and dirt walls and top kept the dried vegetables clean and ready to re-hydrate. SHSND 0086-0437. |

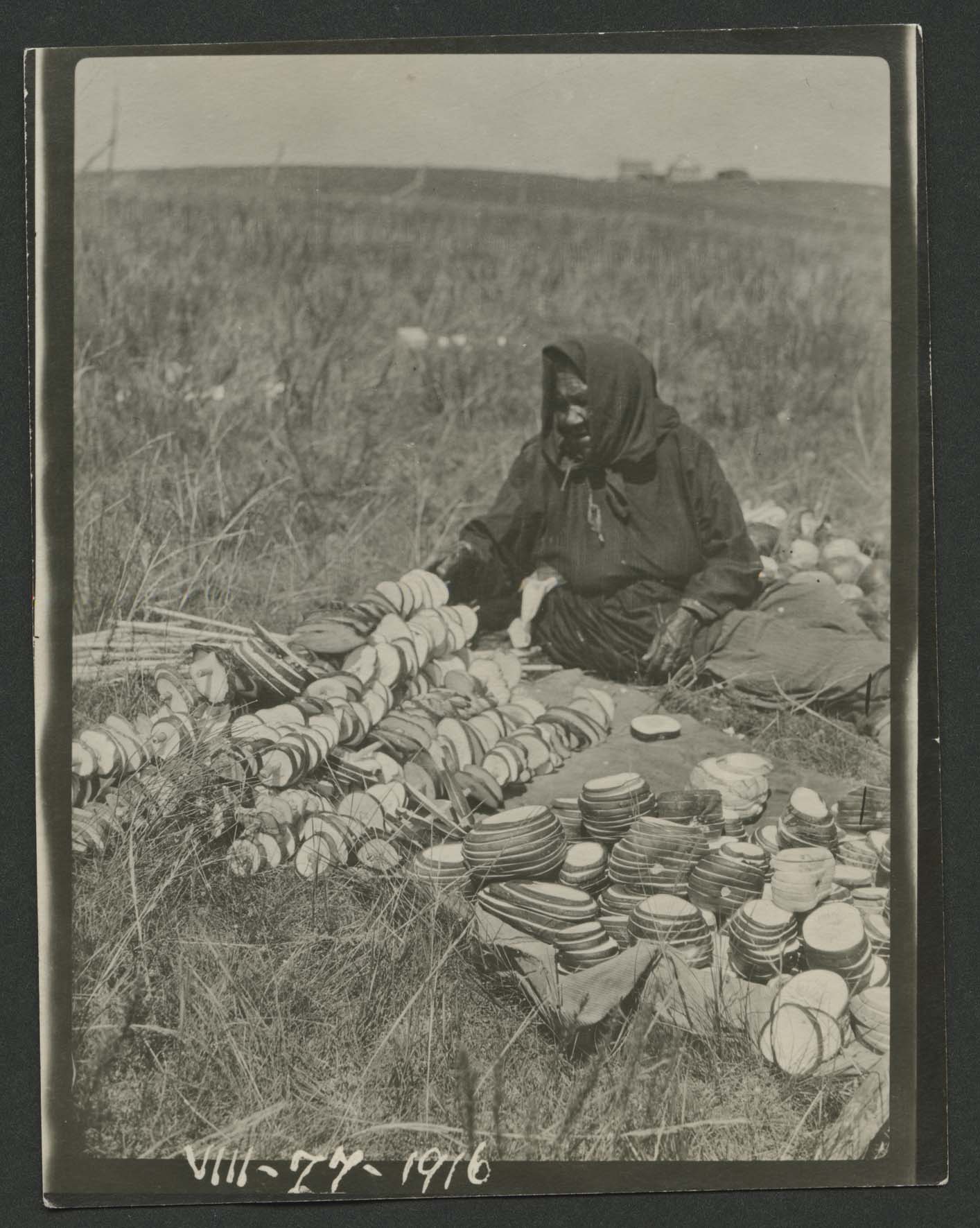

| Source K |

This woman has a string of prairie turnips (Psoralea esculenta). Indian women and children gathered wild vegetables and fruits from the prairies. If not eaten fresh, the vegetables and fruits were dried and stored for winter use. SHSND 0086-0391. |

| Source L |

This woman, of one of the Three Affiliated Tribes, is demonstrating traditional gardening methods. Her hoe is made of a bison scapula (shoulder blade) that is tied to a pole with leather straps. Squash and corn plants are growing behind her. This photo was taken in 1914, but the methods she used would have been the same as when Trobriand was at Fort Stevenson. SHSND 0086-0281. |

| Source M |

Owl Woman drying squash which had been sliced into rings. In winter, these dried pieces of squash (high in vitamin C) will be added to soups and other dishes. This photograph was made in 1916, but the method of drying squash would have been similar to that used in 1870. SHSND 0086-0340. |