History of Oil Extraction

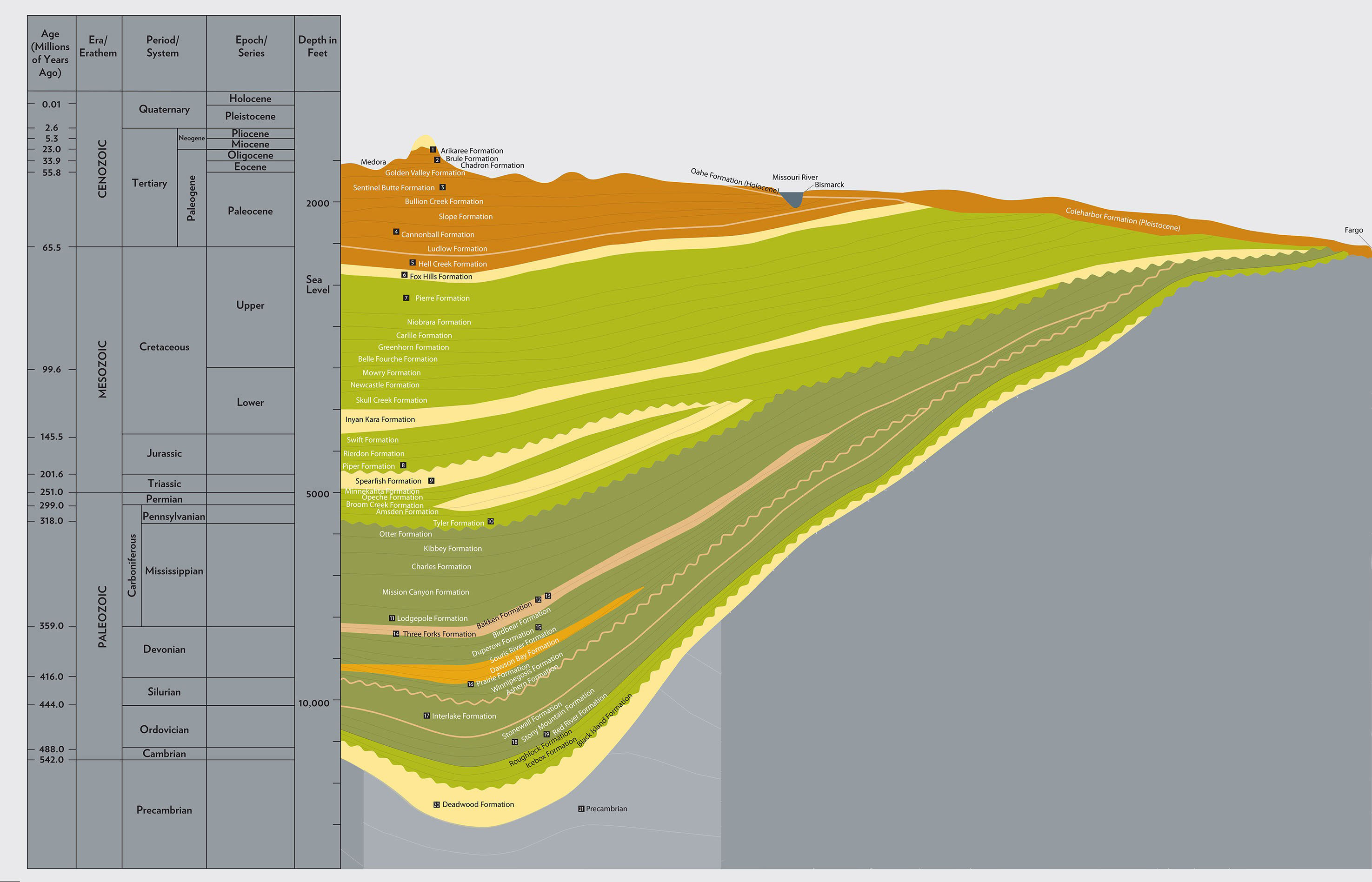

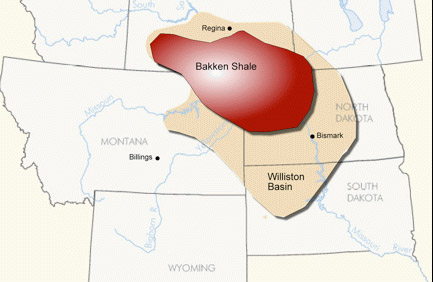

In 1912, a 20-year-old college sophomore named William Taylor ThomTaylor Thom was born in Virginia in 1891. He worked as a page in the U.S. Senate while still in high school. After he graduated from high school, he went to work for the Washington, D.C. Water Development Office. He learned surveying which prepared him for further studies in geology. He attended Washington and Lee University on a scholarship, and then went to Johns Hopkins University where he earned a Ph.D. in geology. After voluntary service during World War I, Thom worked for the U.S. Geological Survey. Later, he became a professor at Princeton University. He continued his study of the geology of North Dakota and Montana for many more years. His work laid the geological foundation for oil development in North Dakota. (known as Taylor) took a job as a surveyor for the U. S. Geological Survey (USGS). Thom was surveying near the Cannonball River in southwestern North Dakota. He found a piece of coral in a stream bed and began to develop a theory that the region had once been part of an ancient sea. He called the geological remains of that sea the Williston Basin. In 1921, Thom, then a geologist with the USGS, prepared a press notice that outlined his idea that the Williston Basin would someday produce oil and natural gas. (See Map 1.)

Over the next 30 years, many test holes were drilled. Some yielded a little oil, but the wells were not technically and economically practical. Thomas Leach, a petroleum geologist, moved to North Dakota in 1936, convinced that the Williston Basin would prove a rich oil field. Leach formed a partnership with Standard Oil and drilled a 10,281 foot deep hole in 1937. There was no oil. Standard Oil pulled out of North Dakota, but Leach continued to look for likely well sites. He leased oil (mineral) rights on thousands of acres.

-Refinery,-American-Oil-Company-036-optimized.jpg)

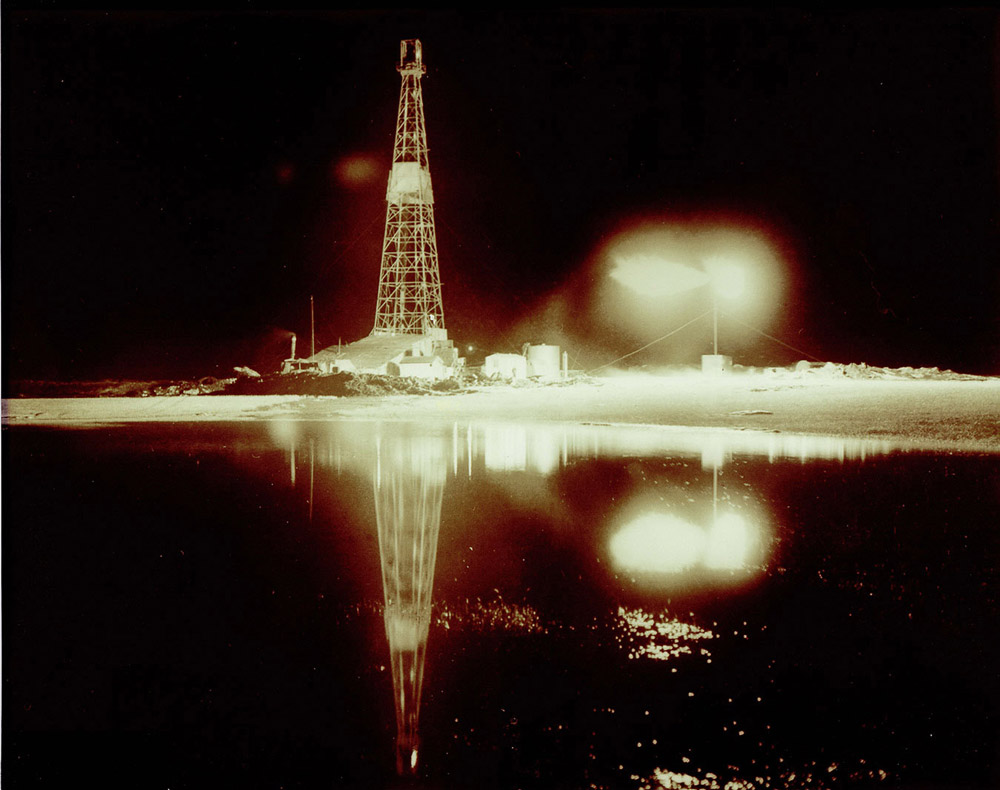

After service in World War II (1941-1945), Leach returned to North Dakota. He formed a partnership with the Amerada Hess oil company to drill in the Nesson Anticline. After months of drilling, the rock was "perforated"Perforating sub-surface rock was similar to fracturing, or “fracking,” shale that is used today to extract oil. Perforating was first used in Pennsylvania in 1864 by A. L. Roberts who invented the Roberts Torpedo. The torpedo was a cast iron shell (much like a cannon shell) that was filled with gun powder. The shell was dropped into a well; a weight was dropped into the well that would strike the gunpowder and cause it to explode. The explosion loosened the rock that held the oil. Oil then would flow from the well. This process was often called “shooting the well.” by explosives more than 11,000 feet below the surface. Finally, on April 4, 1951, Amerada Hess found oil. Following tradition, the well was named for the landowner: Clarence Iverson #1. (See Image 14.) This was North Dakota’s first producing oil well. During the next 28 years, the Clarence Iverson #1 produced 585,000 barrelsOne barrel of oil equals about 42 U.S. gallons. A refinery processes oil into gasoline and other fuel products including jet fuel. One barrel of crude oil can be processed into 19 gallons of gasoline. of oil.

Soon, the entire Williston Basin was busy with oil and gas exploration, drilling, and recovery. (See Document 3.) Within months, more wells were drilled, new mineral leases were written, oil field support companies set up shop in Williston, and plans were made to build a refinery. (See Image 15.) In November, 1952, the Williston Basin oil field produced its one millionth barrel of oil.

Oil companies continued to extract oil from the Williston Basin. During the 1980s, however, oil went "bust."Many industries go through “boom and bust” cycles. When prices are good and demand is high, the industry experiences a boom. When prices fall which happens when demand is low, the industry goes bust. Extractive industries like oil or coal experience these cycles on a regular basis. In 2009, the North Dakota oil industry entered the boom phase of a cycle. The price of oil dropped from $40 a barrel in 1981 to $10 a barrel in 1986. Oil companies closed their offices and laid off workers. The producing wells continued to pump, but towns like Williston and Dickinson felt a great loss as people moved out and schools and houses stood empty.

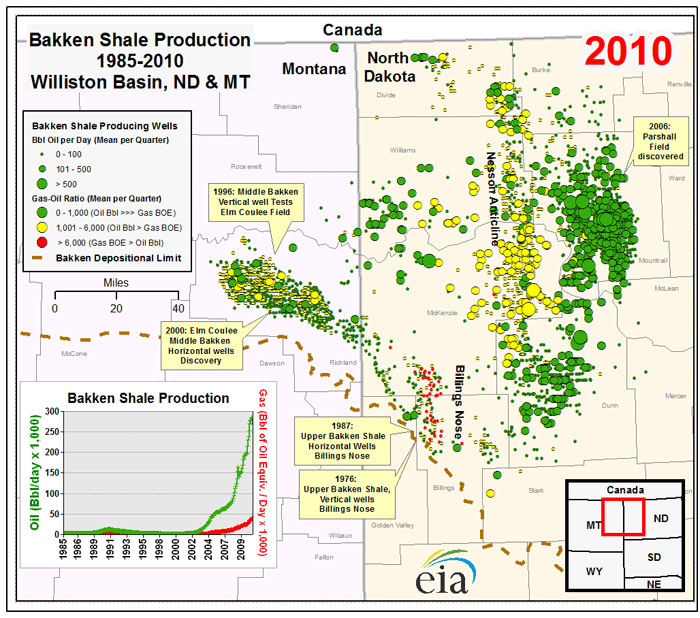

By 1990, the price of oil had recovered, but the next boom cycle would not hit western North Dakota until some vital technological improvements made oil extraction more profitable. (See Image 16.) The first of these changes is called horizontal drilling. In this process, a drill burrows straight down for about 10,000 feet (nearly two miles), and then a slightly curved piece is added to the drill bit that turns the drilling in a horizontal direction. The new technologies were applied to an oil-bearing layer called Bakken located about 10,000 feet below the surface. (See Map 2.)

Fracturing wells is not an entirely new technique, but once it was applied to the Bakken oil layer after 2000, North Dakota oil wells began to produce profitably. (See Map 3.) In 2007, drilling in the Bakken surged. The demand for workers, materials, and support systems grew rapidly. (See Document 4.) Fracturing also called for the use of a mix of water, salt, chemicals, and sand to fracture the rock and to keep the fractures open. Fractured, or “fracked” rock allows the oil to flow toward the well.

Document 4. Oil Statistics

The significance of the Bakken oil formation can be measured statistically. These numbers show growth in production over the last sixty years, and show how technological advances such as fracturing and horizontal drilling have raised production.

Today, the average Bakken oil well will probably produce 615,000 barrels of oil over a lifespan of 45 years. It costs about $9 million to drill and complete a well, but over the years, the well will produce $20,000,000 in net profits.

You can keep up with oil production by checking out the Active Rig Count statistics published by the Oil and Gas Division of the Department of Natural Resources https://www.dmr.nd.gov/oilgas/riglist.asp

|

Year |

Number of Producing Wells |

Total Oil Produced per Year (barrels) |

Average Barrels Produced per Day per Well |

|

1951 |

1 |

26,196 |

72 |

|

1960 |

1551 |

21,993,603 |

39 |

|

1970 |

1624 |

22,006,300 |

37 |

|

1980 |

2401 |

40,446,550 |

46 |

|

1990 |

3579 |

36,723,443 |

28 |

|

2000 |

3340 |

32,735,106 |

27 |

|

2010 |

5355 |

113,065,328 |

58 |

|

2012 |

8373 |

243,246,417 |

80 |

Why is this important? The combination of fracking and horizontal drilling means that oil exploration and drilling in North Dakota is no longer financially risky business. More than 99% of the wells drilled in this manner will strike a good source of oil. It took decades for Tom Leach to find a good source of oil in the Clarence Iverson #1. Today, oil companies can count on success nearly every time they drill a new well. History tells us that technology and the demand for oil will keep western North Dakota oil fields active for many more decades. The Bakken is just the beginning. The Three Forks, a formation just below the Bakken, is already beginning to produce oil.

Concerns in the Bakken

There is a downside to everything, and the Bakken, for all of its advantages, has some serious downsides. North Dakotans are trying to figure out how to live with the costs of prosperity.

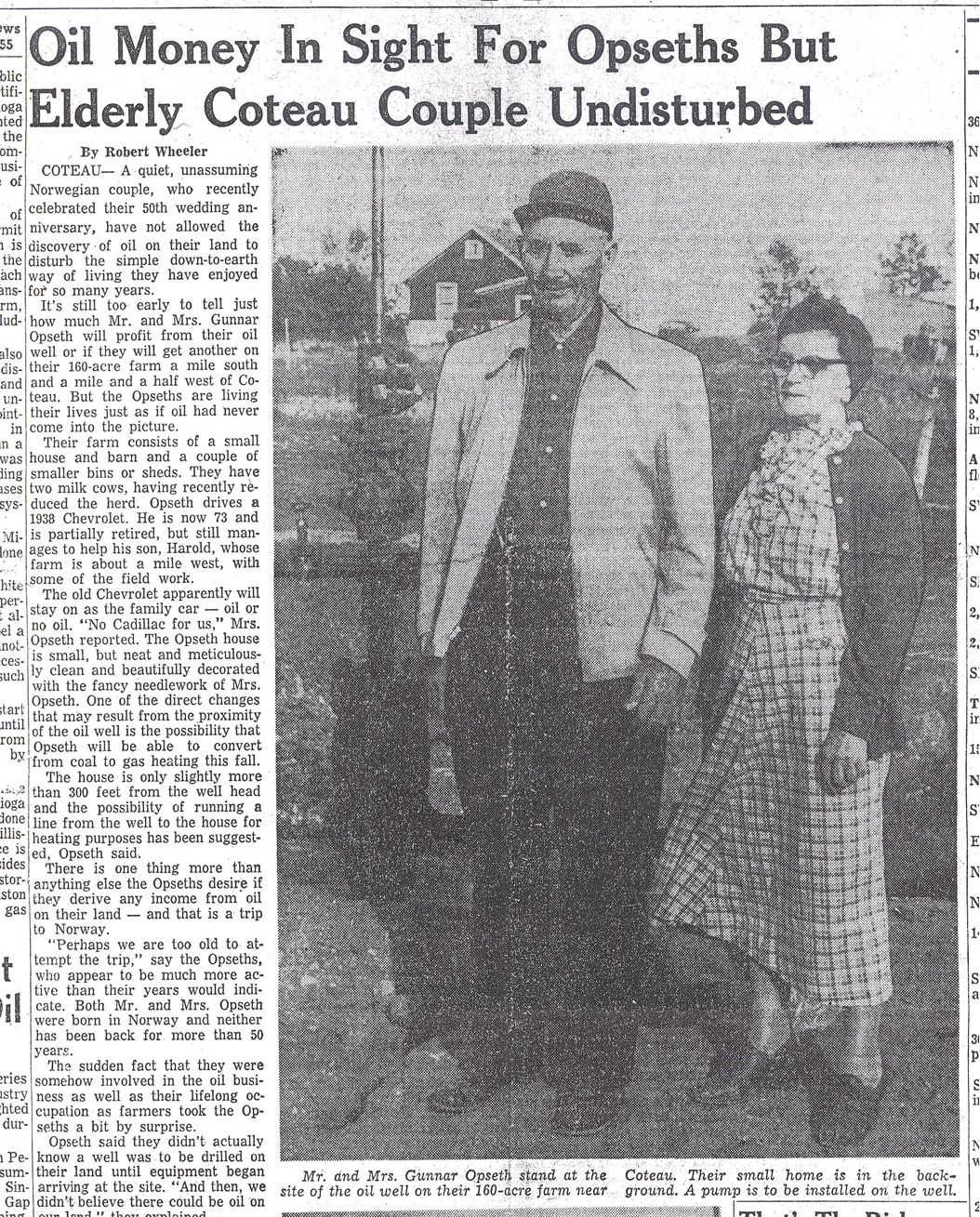

Landowners in the Bakken oil region, many of whom are ranchers or farmers, have had their operations and lives disrupted by oil drilling. If landowners do not also own mineral rights, they may look out the window one day and see a drilling rig on their land. Each well requires hundreds of truckloads of equipment, water, chemical, and sand. Noisy drilling takes place day and night for a week or more until the well has been completed. The dust raised by the trucks settles on pasture grasses that cattle eat. A few ranchers have reported problems with respiratory and digestive health in cattle and dogs.

Traffic accidents and oil well accidents have increased in the western part of North Dakota as the Bakken oil field has developed. Gravel roads, paved county roads, and state highways were built for light traffic and occasional heavy trucks. These roads are not adequate for the high speeds and heavy loads of oil field trucks. In parts of McKenzie County, the county has given responsibility for road upkeep to oil companies because the county budgets could not keep up with the need for improved roads.

Bakken area residents are also concerned about water. Ranchers fear that oil activity could contaminate their wells. The North Dakota Health Department has not found any contaminated well water. In addition, oil companies argue that fracked wells (wells developed by hydraulic fracturing) are safely cased in cement and break the shale rock two miles below the surface. Fracked oil wells are far deeper than water wells. Nevertheless, ranchers worry that careless construction might lead to a break in a well casing that could cause well water contamination. Without clean water, ranchers cannot continue to raise cattle.

In addition to possible contamination, ranchers worry that oil drillers who use well water for fracking will deplete the aquifers (OCK wih furs) that ranchers depend on for their water supply. Many ranchers prefer the oil companies to take their water from Lake Sakakawea as some oil companies do.

Flaring of natural gas imposes a different kind of problem. Every oil well produces some natural gas. This gas is processed for home heating and cooking. There are not enough pipelines in North Dakota to carry the Bakken’s natural gas to processing plants, so excess gas is flared on site. [flare-3] This means that a small pipe carries the gas away from the well. The gas is lit and burns off. About one-fifth of the Bakken’s natural gas is flared at the well. North Dakota is making plans to capture and use more natural gas. In the meantime, the flares are so bright they create light pollution which can be detected from outer space. Images 18 and 19.

Perhaps the greatest concern about the Bakken oil fields is the oil, chemical, and salt (also called brine) spills that have occurred. [Document 5] Every oil well site (sometimes called a pad) has to have a berm, or a raised ring, around the site to prevent spills from running off the oil pad into the nearby soil. When the Missouri River flooded in 2011, some of these berms were overtaken by flood waters. Accidental oil spills have contaminated some farm land. These can be cleaned up by removing the contaminated soil, but it may take months, even years, to finish the job. Spills of salt water produced by fracking can destroy the productivity of the land for years. Chemical spills can contaminate waterways and groundwater. There were 1,100 spills of different amounts involving oil, brine, and chemicals in the Bakken region of North Dakota in 2011.

Disposal of fracking wastes continues to be a problem. In early 2014, there were 400 saltwater disposal wells in the Bakken oil fields. The salt water that is used in fracking is removed as the drilling is completed. It is then injected into wells several thousand feet below the surface. The demand for saltwater disposal wells currently exceeds the number of wells available.

“Socks” present another disposal problem. Filter socks are large filter bags that capture silica dust during fracking. As the water that was poured into the well during fracking returns to the surface, the socks capture the solids in the wastewater. The wastewater may include salt, metals, and other chemicals. About one-third of these materials are radioactive because of naturally occurring radioactive materials (NORM) in the strata (layers of sediment below the earth’s surface) the wells enter. Tons of filter socks are used daily, and, so far, there is limited disposal space in North Dakota. Most drilling companies send the socks to a disposal plant in Colorado, but there have been several incidents of illegal and unsafe “dumping” of filter socks in western North Dakota.

Document 5. Oil, Brine, Chemical Spills

A website that supplies information on oil field (and other) incidents is managed by the North Dakota Department of Health, Environmental Health Division: https://deq.nd.gov/WQ/4_Spill_Investigations/Reports.aspx

The problem of disposal of fracking wastes continues to be a problem. In early 2014, there are 400 saltwater disposal wells in the Bakken oil fields. The salt water that is used in fracking is removed as the drilling is completed. It is then injected into storage wells several thousand feet below the surface. The need for saltwater disposal wells currently exceeds the number of wells available.

“Socks” present another disposal problem. Filter socks are large bags that capture silica dust during fracking. As the water that was poured into the well during fracking returns to the surface, the socks capture the solids in the wastewater. The wastewater may include salt, metals, and other chemicals. About one-third of these materials are radioactive because of naturally occurring radioactive materials in the strata the drills enter. Tons of filter socks are used daily, and, so far, there are no disposal facilities in North Dakota. Most drilling companies send the socks to a disposal plant in Colorado, but there have been several incidents of illegal and unsafe “dumping” of filter socks in western North Dakota.

Why is this important? Recent development of the Bakken oil fields has proceeded at a very rapid pace. Residents in and out of the oil patch wonder how we might gain control over the problems that seem at times to overwhelm the advantages. However, North Dakotans have met and solved many problems over the thousands of years people have occupied the northern Great Plains. Drilling for oil in the Bakken oil fields presents North Dakotans with a new set of problems. We can solve oil field problems of waste disposal, clean water, flaring, and human safety in the same way we have resolved problems in the past. We apply community efforts to create political change and technical and scientific advances.