When North Dakotans voted in 1918, they found Nonpartisan League (NPL)When studying the Nonpartisan League, it is important to remember that at that time, most of Europe was engaged in a very long and bloody war. Russia had entered the war under the leadership of the Czar Nicholas, but by 1917, Russia faced revolution led by socialists and communists. Russian soldiers left the war front and returned home forcing Russia to withdraw from the war.

World leaders watched the Russian Revolution with great concern. Most considered communism and socialism to be detrimental to their nations’ interests. Americans knew that socialists were sitting in North Dakota’s legislature and empowering the state to own and operate businesses. Many Americans were concerned that North Dakota would become a socialist state. candidates on the ballot again. Despite growing opposition, Lynn Frazier was once again elected governor and other NPL candidates also fared well. The NPL controlled both houses of the sixteenth session of the North Dakota legislature that met in 1919.

Opposition to the NPL came from a new organization with the sole purpose of throwing the NPL out of office. The organization was called the Independent Voters Association or I.V.A. Most I.V.A. members lived in cities and towns. The I.V.A. was led by Theodore G. Nelson, known as “Two-bit” Nelson. Nelson was a former member of the American Society of Equity and the NPL, but he had concerns about socialism and left the NPL to try to defeat the organization.

The NPL legislative caucus was still making decisions under the close supervision of A. C. Townley and League lawyer William Lemke. The NPL legislators began to propose and pass bills that would put the League’s plan into action. New laws set up the State Bank of North Dakota, the Industrial Commission (composed of the governor, attorney general, and commissioner of agriculture and labor), and the State Printing Commission. New tax laws resulted in higher tax revenue (income) because railroads were now taxed at a fair value.

The Bank of North Dakota was to be financed by $2,000,000 worth of bonds. The state had to sell bonds to investors to get enough money to start the bank. There were few investors willing to engage with North Dakota’s socialist experiment, so the bonds did not sell well. (See Image 8)

However, city, county, township, and school district funds were deposited in the state bank. All state, county, municipal, and school agencies were required to deposit all of their funds in the State Bank. By September, these deposits ($8,700,000) amounted to more than the bond issue. Banks around the state also began to make deposits in the State Bank. With these deposits, the State Bank had a successful opening. The State Bank also re-deposited some of its money in small banks around the state which helped those banks and made loans to farmers at 6% interest (the usual rate was 8.7%.)

The Bank of North Dakota also made large deposits of money in the NPL-owned Scandinavian American Bank of Fargo, increasing that bank’s profits and moving more money into Cass County than any other county.

Why is this important? Some of the NPL laws of 1919 were quite successful. The Bank of North Dakota and the State Mill and Elevator met many of the demands that farmers had been making for 30 years. Other laws, such as the State Printing Commission law, led to more conflict within the NPL. With the 1919 legislature, the NPL was able to meet most of the planks in its platform, but it reached too far beyond its platform. Many of the laws seemed too costly, gave too much political control to state officials, and tended to undermine the people’s political powers.

The success of the NPL led directly to the rise of organizations that opposed the League’s plan. After 1920, many League officials faced charges of corruption and many League laws were modified or overturned by subsequent legislatures.

The State Mill and Elevator

In 1886, H. L. Loucks, president of the Farmers’ Alliance complained that under railroad control, farmers were “compelled . . . to pay tribute to the Elevator companies.” In 1893, a group of Valley City farmers petitioned the legislature for relief from millers’ “unbounded greed” which was “greater than they can bear.” (See Document 5) For decades, North Dakota farmers had asked the state to build a terminal elevator,Grain elevators are tall, tower-like buildings, usually located next to railroad tracks, where grain is scooped up for storage in a tall silo. A local or country elevator is where farmers took their grain for storage until the railroad picked up the grain and transported it to a terminal elevator in Minnesota cities of Minneapolis, St. Paul, or Duluth. At a terminal elevator, the grain was either milled (turned into flour) in Minnesota, or it was prepared for export to another country. None of North Dakota’s grain elevators were terminal elevators.

Farmers received a low price for their grain in North Dakota because the grain would be shipped a great distance before milling. Farmers also had to pay storage fees to the elevators. Many farmers believed that a terminal elevator in or owned by the state of North Dakota would give farmers a better price for their grain.

Many grain dealers cheated farmers by giving the wheat a lower grade than it deserved. Many farmers delivered No. 1 Hard Red Spring Wheat to the local elevator. Some greedy grain dealers, however, graded the wheat as Number 2 or Number 3 Hard. The lower grades brought in a lower price per bushel. Farmers wanted the state to establish a grain grading system to ensure that they received the best price for their crops. for grain-trade and railroad regulation, for official grain-grading systems, and for a state-owned elevator. The 1917 legislature passed a terminal elevator bill, but Governor Frazier vetoed the bill.

In 1919, the legislature approved a bill funding the construction of a state mill and elevator in North Dakota. Governor Frazier signed the bill. The bill authorized the North Dakota Mill and Elevator Association to create a “system of warehouses, elevators, flour mills. . . .” The Industrial Commission (the governor, attorney general, and commissioner of agriculture and labor) was to oversee the work of the Mill and Elevator Association.

The bill creating the Industrial Commission faced strong opposition. The bill (House Bill 17) established a state agency with the authority to manage “utilities, industries, enterprises and business projects” on behalf of the state. The law became effective as soon as it was signed by the governor. The Independent Voters Association petitioned to hold a referendum on the law so that voters could approve the law directly. The referendum was held on June 26, 1919.

The Bismarck Tribune encouraged its readers to reject the Industrial Commission bill at the special election. Because the Industrial Commission was made up of elected officials, the editors feared that the commission’s work would change every two years. The voters, however, approved the Mill and Elevator Association and the Industrial Commission. The Tribune made a careful analysis of votes, and notified its readers of a growing weakness in the League’s popularity.

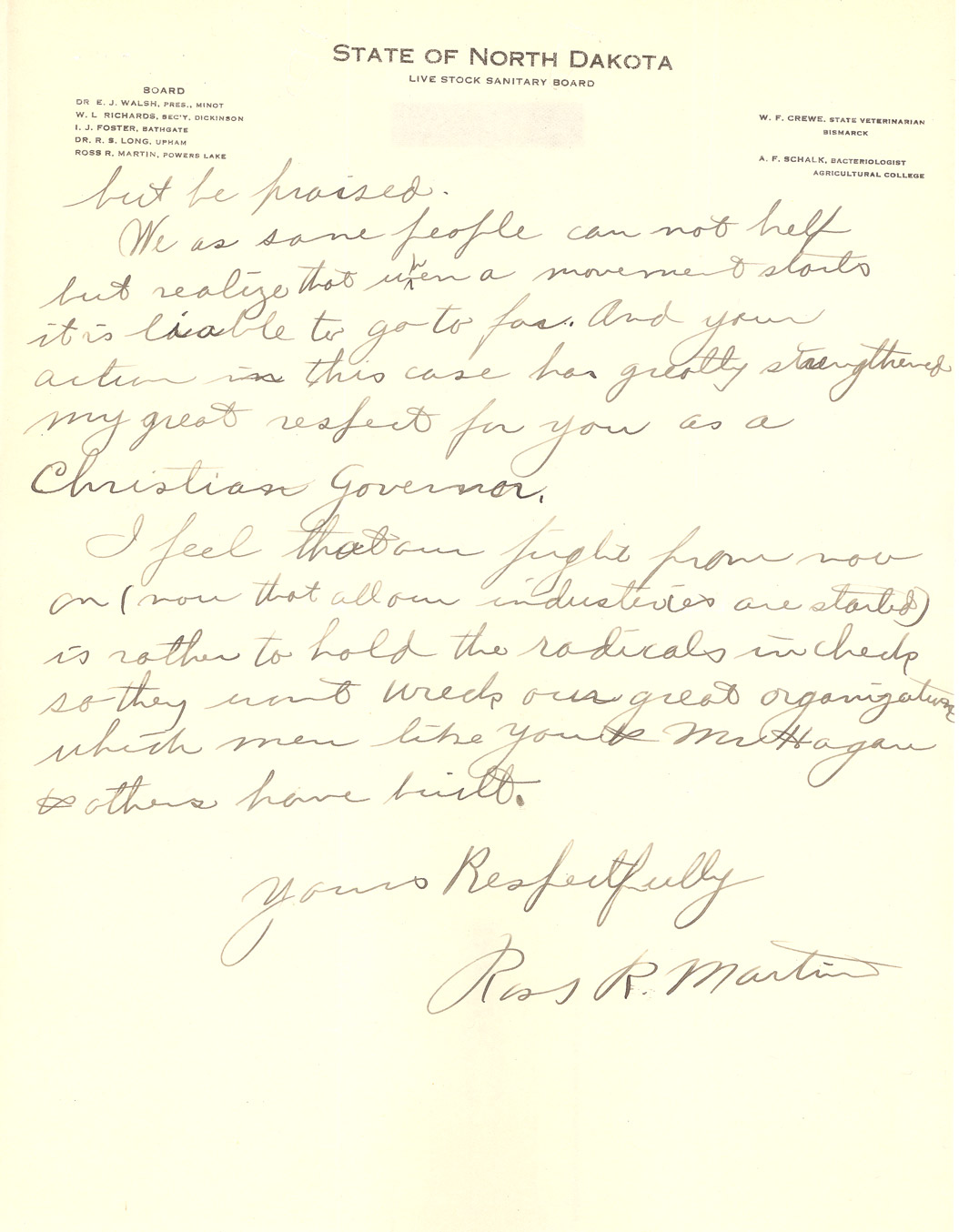

With the support of the people, the state moved ahead to create the State Mill and Elevator. The Mill and Elevator Association purchased an existing elevator and mill at Drake. (See Image 9) This mill was too small and out-dated to meet the farmers’ needs. The Drake Mill operated at a loss for several years and closed in 1924. Opponents of the Nonpartisan League (NPL) used the failure of the Drake mill to criticize the entire NPL program. (See Document 6)

The Mill and Elevator Association selected Grand Forks as the site of a modern, large mill and elevator complex. Construction began in 1919 and proceeded irregularly for several years. (See Image 10) Political events interfered with construction progress, but it finally opened late in 1922. The mill was not profitable for several years due to political events and mismanagement. By the late 1930s, the problems had been solved and the mill began to make a profit. The income from the mill and elevator is paid to the State of North Dakota. (See Image 11)

Why is this important? There are many good economic reasons why the State Mill and Elevator have been important to North Dakota. The agencies are usually profitable. The income has contributed to the state’s good financial condition. Farmers had access to the terminal elevator and state regulation of the grain trade that they had asked for.

Historically, the Mill and Elevator are two of the three institutions (along with the State Bank) created by the NPL during its short term in state government that remain with us today. No other state had ever attempted ownership and management of such large enterprises, so North Dakota was deeply engaged in an economic experiment with no previous model to follow. It is not surprising that the Mill and Elevator and the State Bank both muddled through periods of mismanagement and suffered from political interference before they reached operational “maturity.”

Though the state’s “socialist experiment,” as it was called in the 1920s, is in our past, the three experimental institutions remain viable. Today, other states are looking carefully at North Dakota’s experiment to see if their states might also profitably engage in state ownership of some institutions.

More on the history of the state mill and elevator: http://history.nd.gov/archives/stateagencies/millandelevator.html

The Newspaper Bill

Long before the Revolutionary War, Americans learned the power and importance of a free press. So important was the press to a free democracy, that the members of the constitutional convention wrote the idea into the first amendment to the Constitution of the United States in 1789. The first amendment reads:

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

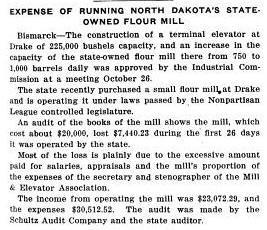

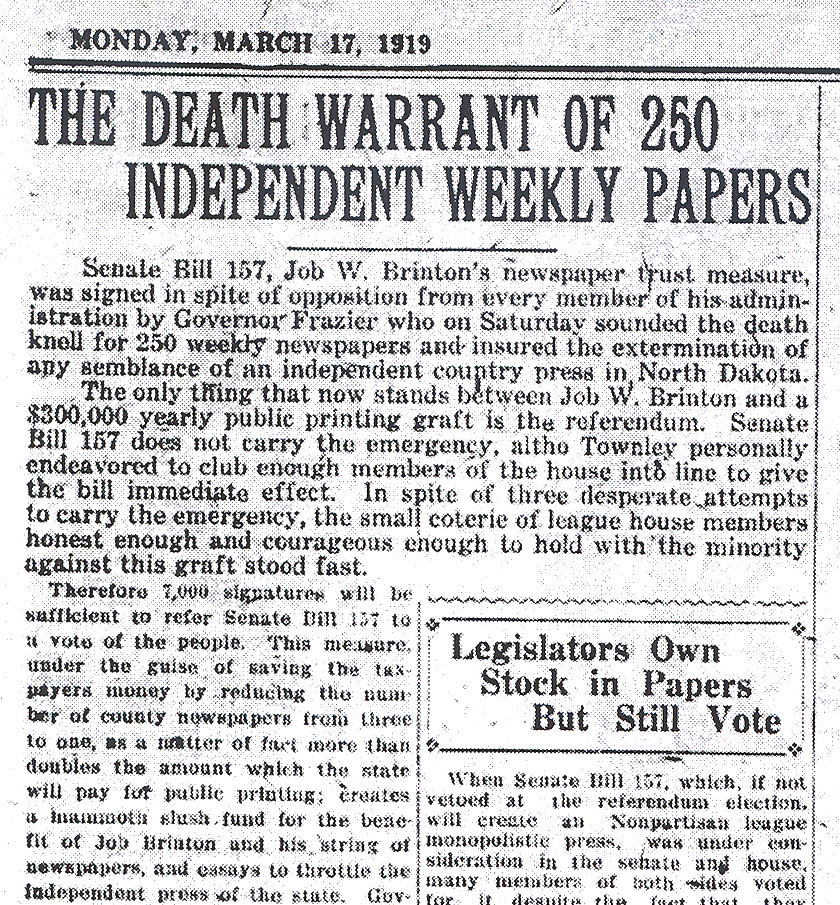

In North Dakota, freedom of the press was restrained by a law passed by the 1919 legislature that was dominated by the Nonpartisan League (NPL). (See Document 7) Senate Bill 157, also called “Job W. Brinton’s newspaper trust measure,” was signed by Governor Lynn Frazier over the objections of Attorney General William Langer, Auditor Carl Kositzky, and Secretary of State Thomas Hall. (See Document 8) Senate Bill 157 created a State Printing Commission which was to choose an official newspaper for each county. The official newspaper would earn as much as $20,000 each year printing official state, county, and city notices. (See Document 9)

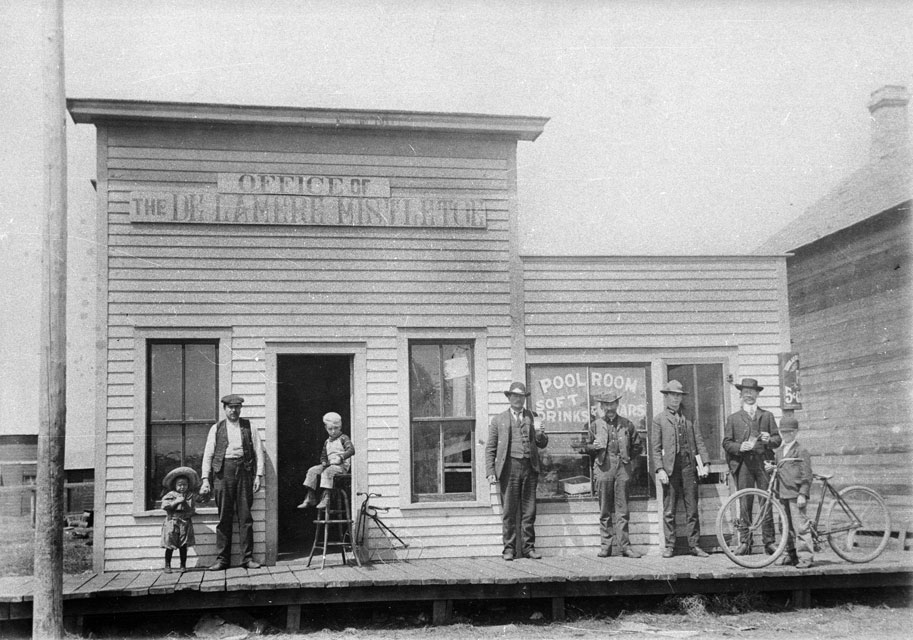

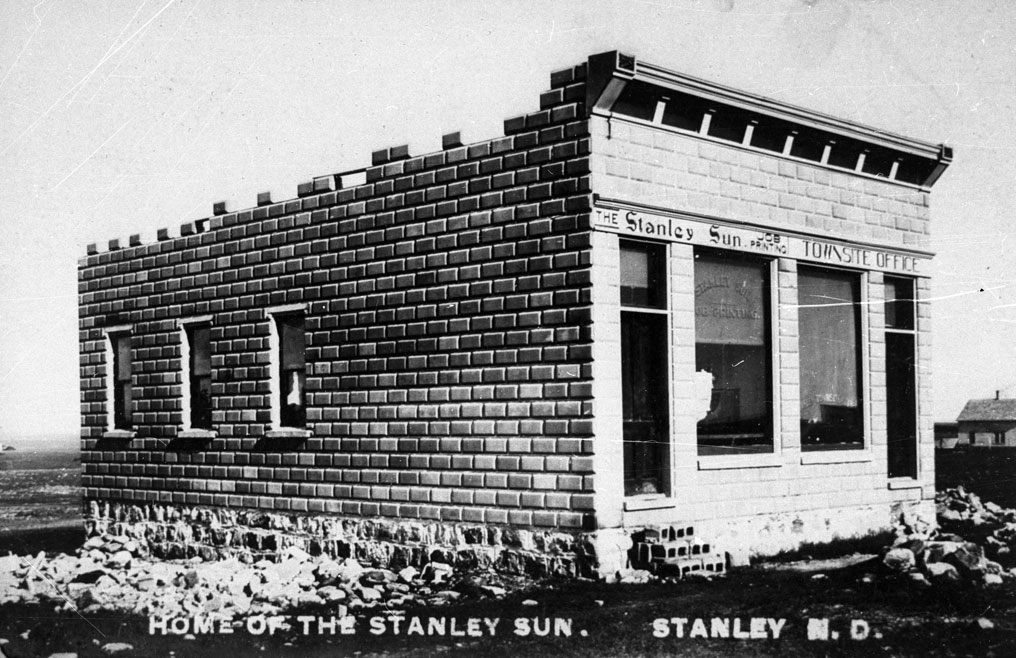

Before the passage of this bill, each county had three official newspapers. (See Image 12) In the lightly populated counties of North Dakota, the regular income from printing official notices paid the bills for many newspapers. It would be difficult for a newspaper to remain in business if it did not print official notices.

The commission chose newspapers that were either owned by the NPL or favored the NPL policies. Many legislators owned stock in NPL newspapers, but did not excuse themselves from voting on the bill. (See Image 13)

The bill was very effective. By the end of 1919, 61 weekly newspapers had gone out of business. Within five years, more than 200 newspapers had ceased publication.Many small-town and county newspapers published official state notices and notices of homestead proofs. When a person claiming land under the Homestead Law had met all the requirements of the law, he or she had to put a notice in three editions of the local newspaper. Both official state and county notices and homesteader proof notices kept many small newspapers in business. No doubt, many of these newspapers would have gone out of business as the printing of homesteader proofs ceased in the early 1920s. (See Image 14) Though some Leaguers claimed that the bill would save the state money, the Bismarck Tribune argued that the funding of the State Printing Commission, headed by J. W. Brinton, would cost the state more than the former system of paying for official notices.

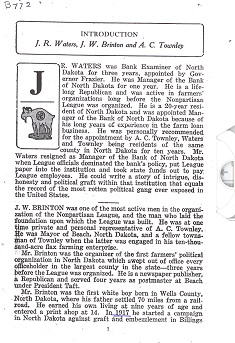

Job Wells Brinton, who would serve as a member of the Printing Commission, had been the outspoken editor of the Beach newspaper, the Golden Valley Chronicle. He had championed farmers’ interests in his newspaper.Brinton’s concern for farmers’ rights was sincere. On May 21, 1915, Brinton (mayor of Beach and editor of Golden Valley Chronicle), wrote an editorial critical of the competing newspaper, the Beach Advance which had published an article on farmers. This editorial was written just two months after the founding of the Nonpartisan League. He wrote: This newspaper [the Beach Advance] – if it can be called that – has called the farmers “pinheads”, “woodheads”, “bulletheads”, etc., when they did not agree with and support the political activity of this particular [newspaper]; now they are calling the farmers “dummies” because they are organizing a produce company and a farmers’ store. . . . If it were not for the “dummy” farmers referred to by this businessmen’s paper, so-called, who make up the different boards of directors and stockholders in the elevator companies, creameries, cheese factories, produce companies and numerous other farmer organizations, including farmer stores, the county would not have any of these enterprises doing business today. You can rest assured they were not promoted by business men nor supported by such newspapers as the Beach Advance. The country wants more “bonehead” farmer organizations, more “woodhead” farmers in politics and more “dummy” farmer-made laws, if the Advance uses the correct terms when speaking of the farmers. – [signed J. W. Wells,] Mayor of Beach, Golden Valley Chronicle, Friday May 21, 1915, page 1. Brinton challenged public officials to recognize the value of farmers’ political and economic contributions to their communities. While working in Beach, he had met and befriended Arthur C. Townley. (See Document 10) He became an early organizer for the NPL in western counties and worked very closely with Townley on League issues. In 1917, he organized the Consumers United Stores, another League program.

Brinton owned several League newspapers. He stood to gain personally from Senate Bill 157. He probably saw it as a means of uniting people behind the League. His interest in supporting farmers was sincere. However, by 1919, Brinton had accused Townley of embezzling NPL funds. Along with other League officials such as Bank of North Dakota Manager J. R. Waters and Attorney General William Langer, Brinton publicly accused Townley of embezzlement and fraud.

Why is this important? The Nonpartisan League often overstepped the legitimate concerns of a political organization. The case of Brinton’s Law is a good example of the League abusing its political power. This law is one of many instances which caused many League members to doubt the quality of leadership in the League. Brinton, Langer, and others eventually helped to form organizations to reduce the control of the NPL over state government.

Brinton’s Law shows how a good idea can go bad if the people who put that idea into action do not remember fundamental constitutional and democratic principles. The 1921 and 1923 legislatures did not have a majority of NPL members. Both legislatures amended Senate Bill 157 (Chapter 187, 1919 Laws of North Dakota) to allow voters to choose the official county newspaper. Though the undemocratic qualities of Brinton’s Law were removed from the law books, North Dakota never again had as many newspapers as it had before 1919. In 1910, there were 344 newspapers (both daily and weekly) published in North Dakota. Today, North Dakota has ten daily newspapers and 80 weekly newspapers.

Letters to Governor Frazier

The governors’ files in the State Historical Society of North Dakota are filled with letters from citizens who ask the governor for help in solving a problem. Governor Frazier, the NPL governor (1917 – 1921) received many letters from citizens who were members of the NPL or expected the NPL governor to take their side in their battles against the railroads or coal mines.

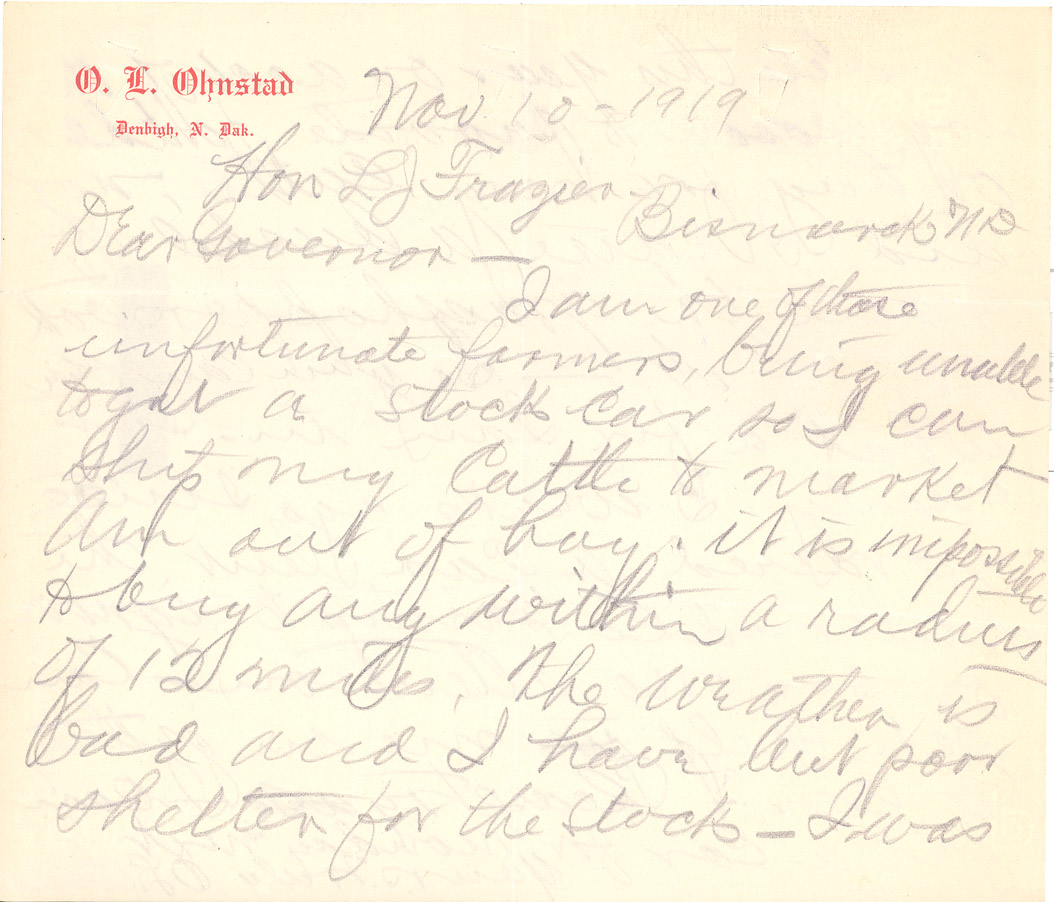

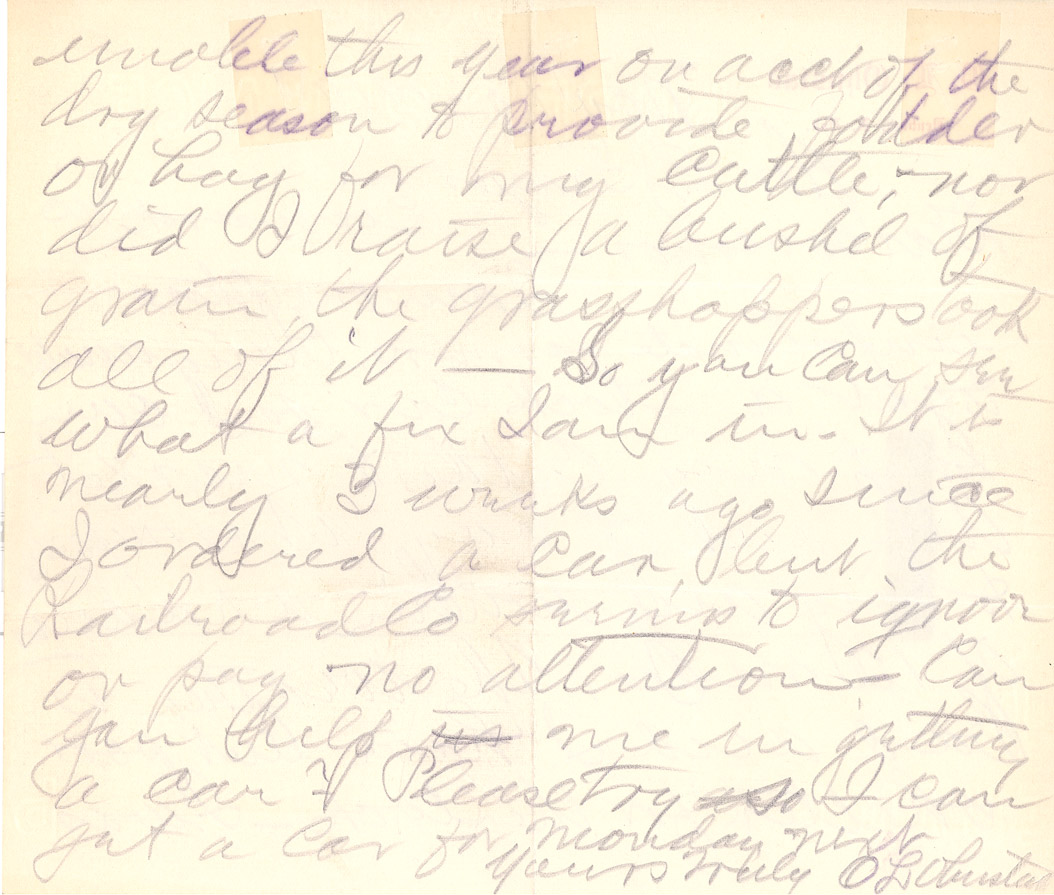

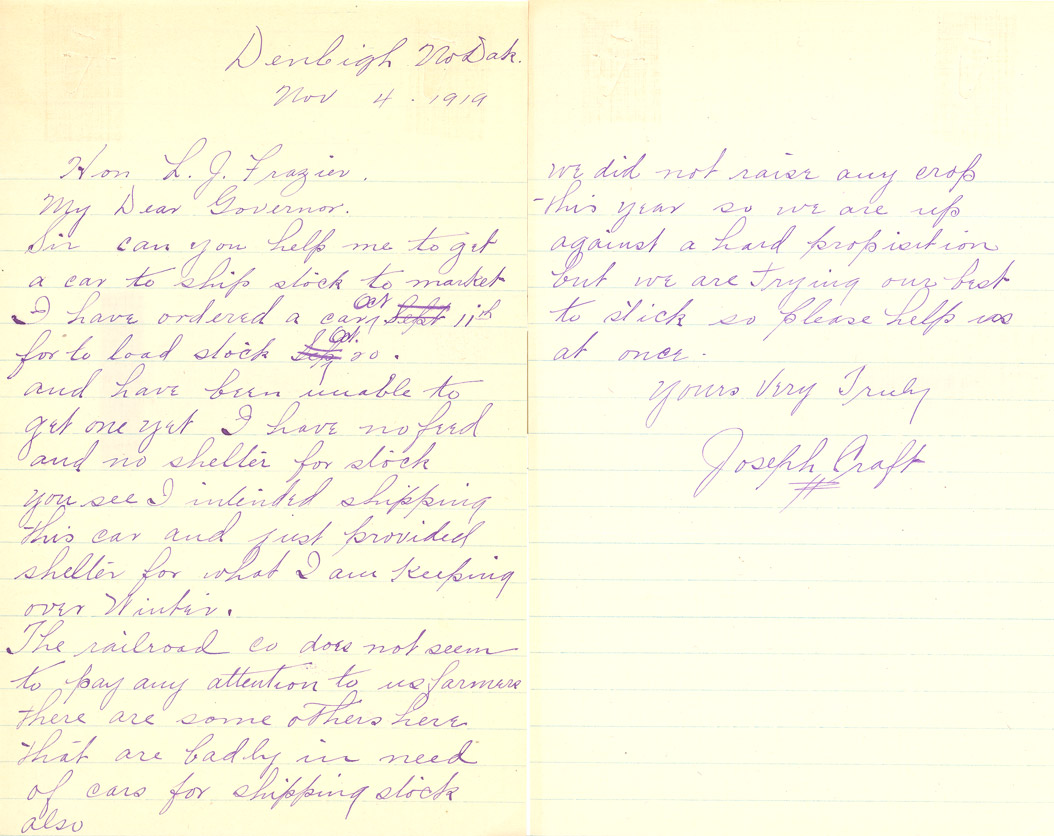

Two of these letters addressed to Governor Frazier in 1919 were written by farmers who were trying to arrange for a cattle car to ship their excess livestock by rail to another location. The railroads had not sent a car (as was the common procedure in 1919) and the men had no feed for their livestock. As the starving animals lost weight, the farmers lost money.

Joseph Craft uses a phrase which identifies him as a member of the NPL. In his last sentence, he says “we are trying our best to stick.” (See Document 11 and Transcription) The NPL used the phrase “We’ll stick,” especially as the organization came under fire from the Independent Voters Association and other opponents. “Stick” also means that Mr. Craft was facing desperate times. The summer of 1919 had brought little rain to the farms, so there was no feed for the livestock and little in the way of crops to sell. If Mr. Craft was unable to sell his cattle, he might have to leave his farm. (See Document 12 and Transcription)

Document 11 and Transcription

Denbigh NoDak.

Nov 4 1919

Hon L. J. Frazier.

My Dear Governor.

Sir can you help me to get a car to ship stock to market I have ordered a car Oct Sept 11th for to load stock Sept Oct 20. And have been unable to get one yet I have no feed and no shelter for stock you see I intended shipping this car and just provided shelter for what I am keeping over Winter.

The railroad co does not seem to pay any attention to us farmers there are some others here that are badly in need of cars for shipping stock also.

We did not raise any crop this year so we are up against a hard propisition but we are trying our best to stick so please help us at once.

Yours Very Truly

Joseph Craft

#

Document 12 and Transcription

O. L. Ohnstad

Denbigh, N. Dak. Nov 10 – 1919

Hon L. J. Frazier –

Bismarck ND

Dear Governor –

I am one of those unfortunate farmers being unable to get a stock car so I can ship my cattle to market Am out of hay. It is impossible to buy any within a radius of 12 miles. The weather is bad and I have but poor shelter for the stock – I was unable this year on account of the dry season to provide fodder or hay for my cattle, nor did I raise a bushel of grain the grasshoppers took all of it – So you can see what a fix I am in – It is nearly 3 weeks ago since I ordered a car, but the Railroad Co seems to ignore or pay no attention – can you help us me in getting a car – Please try so I can get a car for Monday next

Yours truly O L Ohnstad

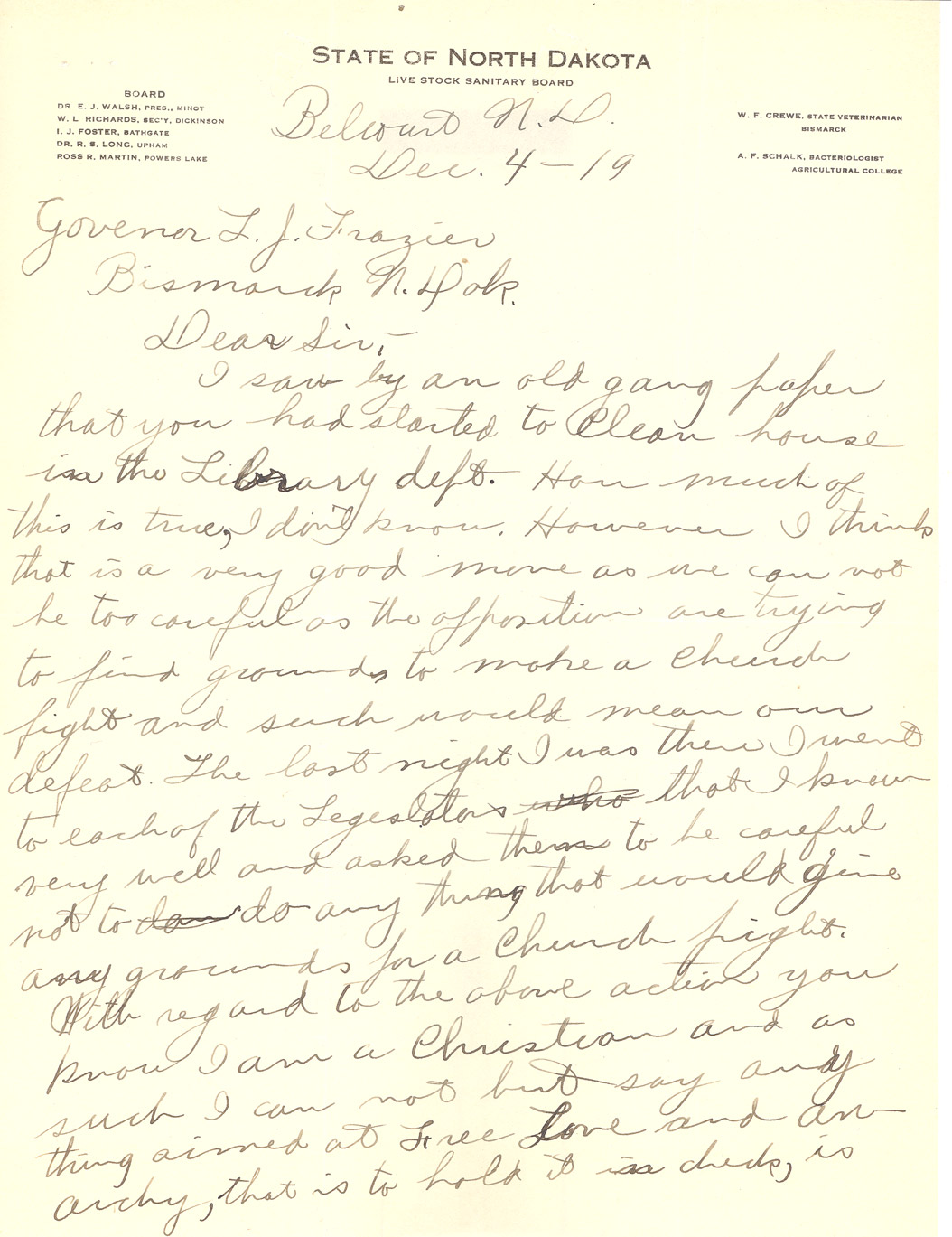

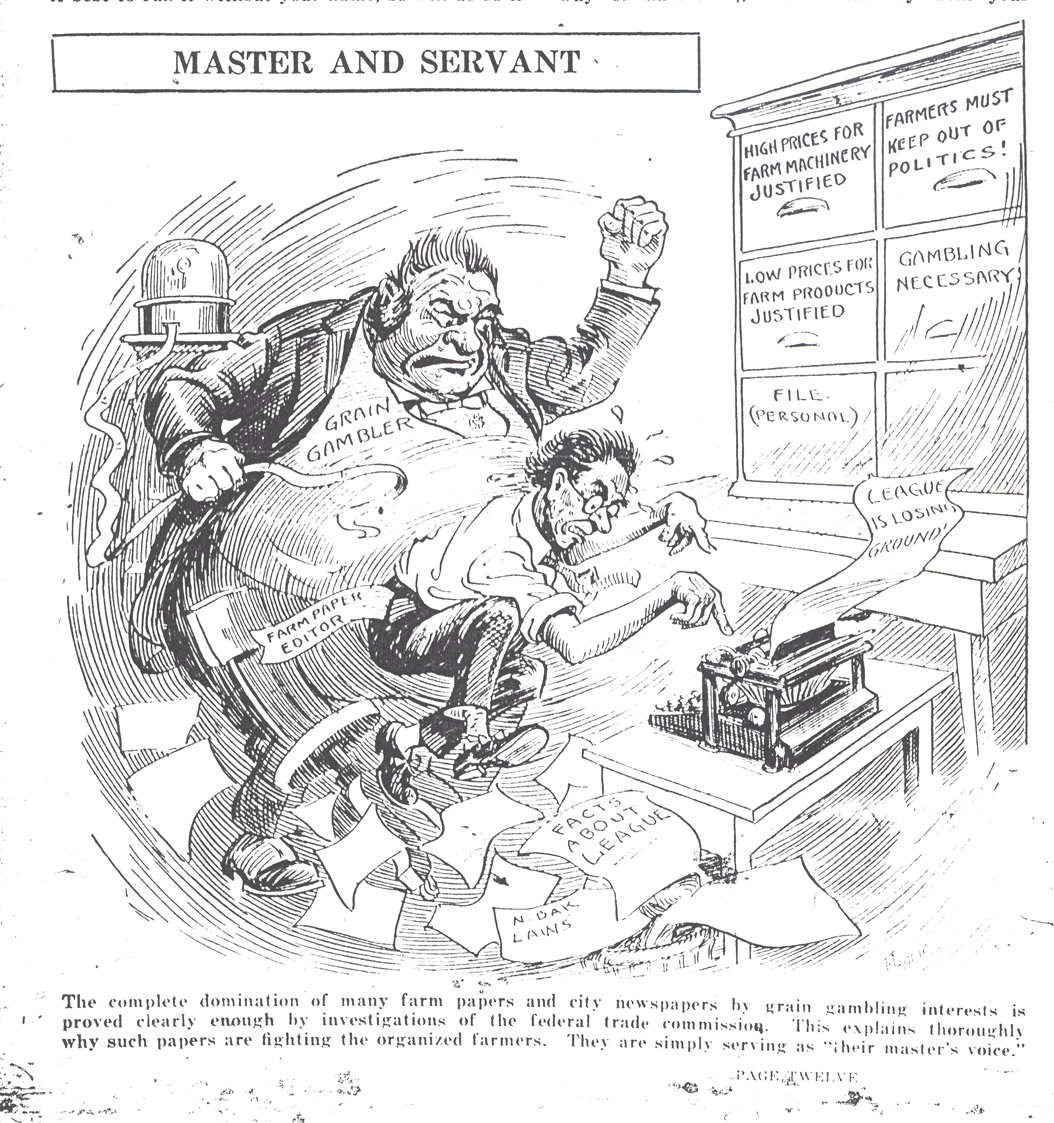

Document 13 and Transcription

Belcourt N.D.

Dec. 4-19

Governor L. J. Frazier

Bismarck N. Dak.

Dear Sir, -

I saw by an old gang paper that you had started to clean house in the Library dept. How much of this is true, I don’t know. However I think that is a very good move as we can not be too careful as the opposition are trying to find grounds to make a church fight and such would mean our defeat. The last night I was there I went to each of the legislators that I know very well and asked them to be careful not to do any thing that would give any grounds for a church fight.

With regard to the above action you know I am a Christian and as such I can not but say any thing aimed at Free Love and anarchy, that is to hold it in check, is but be praised.

We as sane people can not help but realize that when a movement starts it is liable to go to far. And your action in this case has greatly strengthened my great respect for you as a Christian governor.

I feel that our fight from now on (now that all our industries are started) is rather to hold the radicals in check so they wont wreck our great organization which men like you Mr. Hagan & others have built.

Yours Respectfully

Ross R. Martin

The third letter is from an NPL member who worries that opponents of the NPL will attack the organization as un-Christian. (See Document 13 and Transcription) Governor Frazier has recently acted to remove a book in the state library that advocated “free love.” He defends the NPL and Governor Frazier by stating that the organization is not about “Free love and anarchy.” He also praises Frazier as a “Christian governor.” (See IVA)

These letters have been scanned from the files of Governor Frazier and transcribed as they were written. Spelling and grammar errors have been retained for historical accuracy.

Source: SHSND 30153, File 1.