One concern of the progressive movement was the quality of food that people ate. Progressives were especially concerned about canned or processed foods such as ketchup and drugs such as cough syrup. Before 1906, processed foods and most pharmaceutical drugs were prepared without any oversight as to purity, quality, or sanitation.

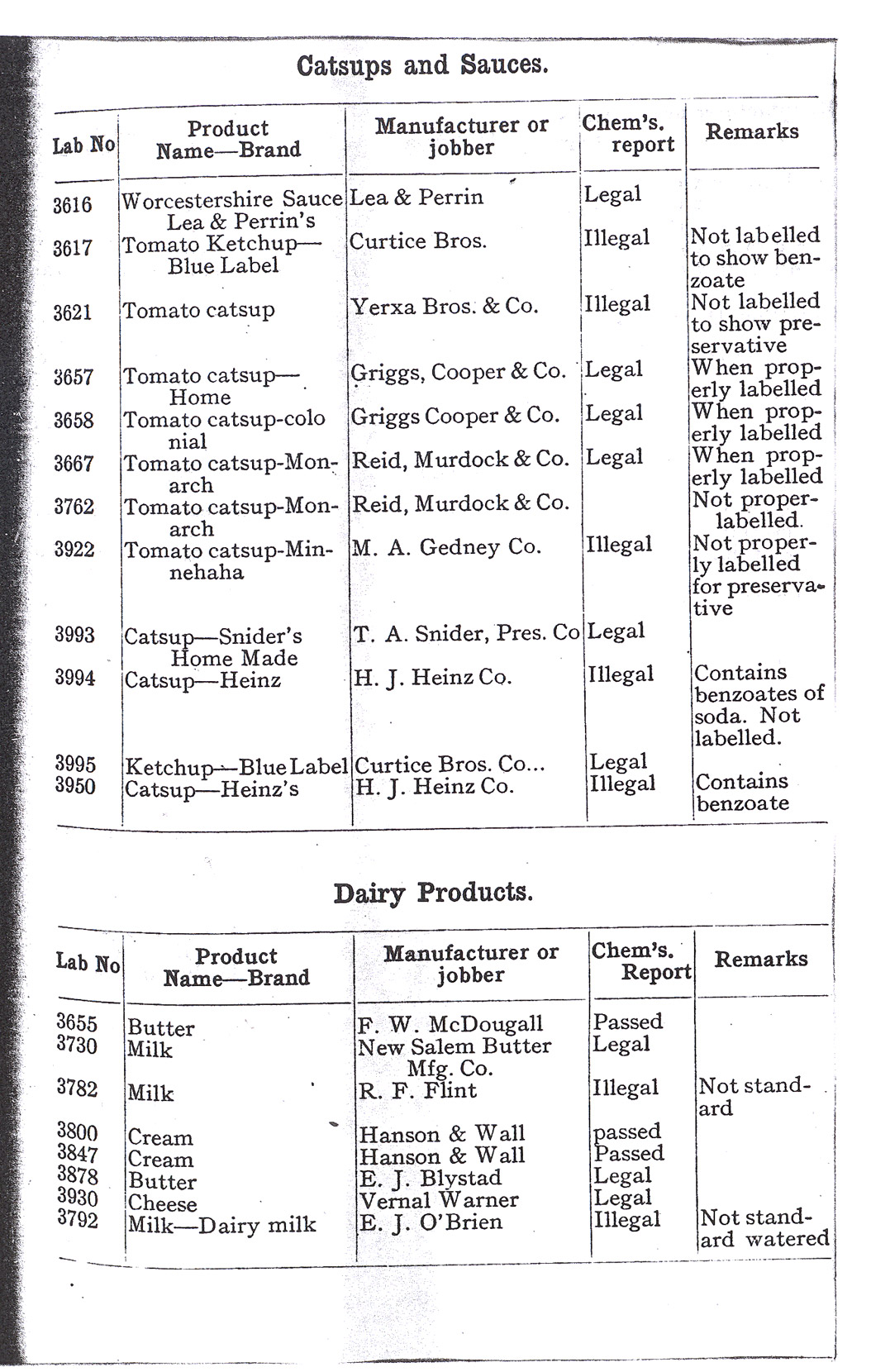

One of the heroes of the pure food and drug movement was Edwin F. Ladd (1859-1925) (See Image 2), professor of chemistry at North Dakota Agricultural College (NDAC) in Fargo. Ladd was born in Maine where he received a very good education. He studied science and agriculture at the University of Maine. In 1890, Ladd accepted a position at the newly organized agricultural college in Fargo (today’s North Dakota State University.)

While Ladd’s colleagues thought very highly of him, they also said that he was an “unimaginative” teacher, very stern, and “obsessed with an analytical approach to chemistry.” However, his devotion to high standards in his work served him well as a leader of the pure food and drug campaign.

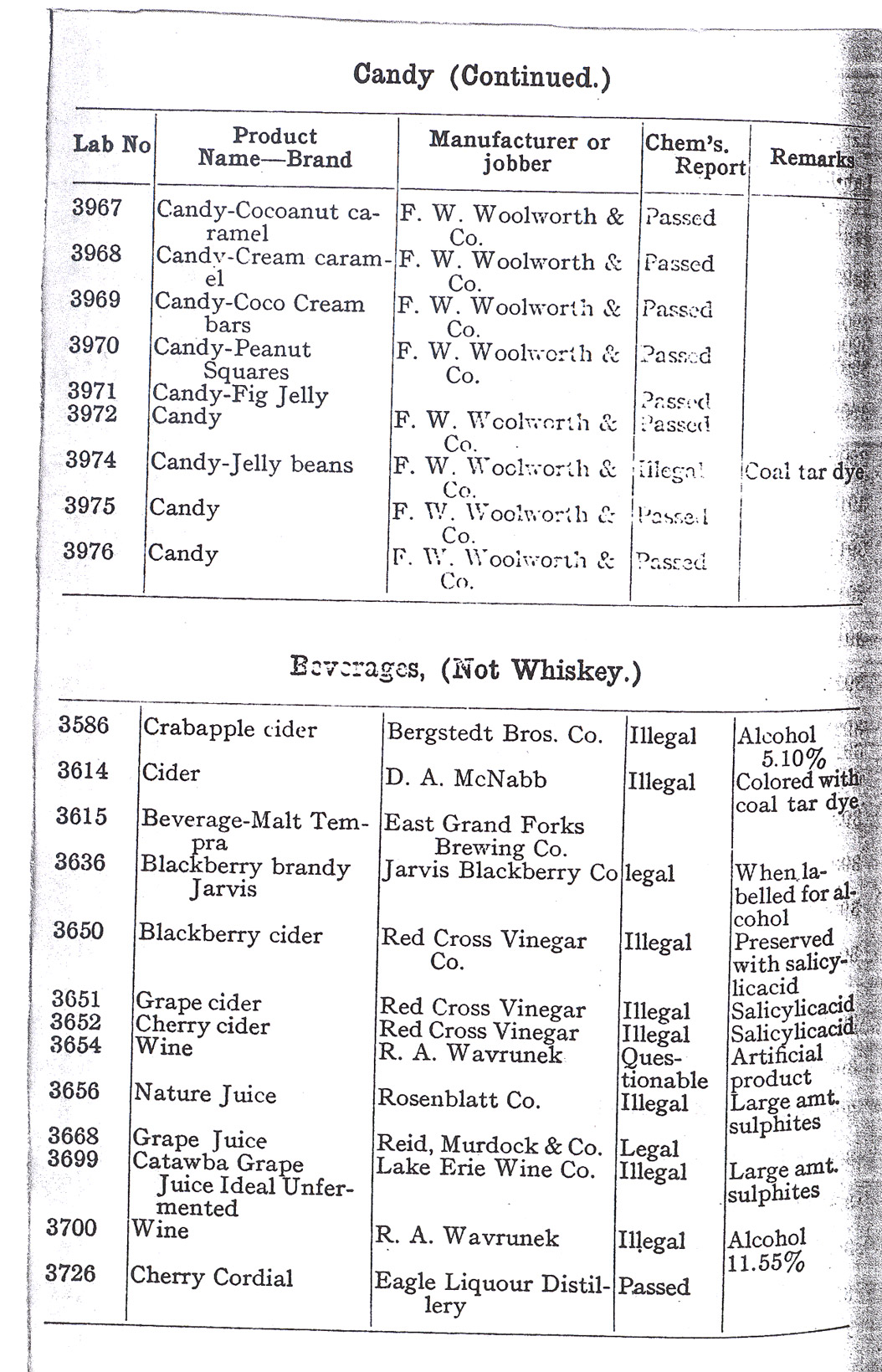

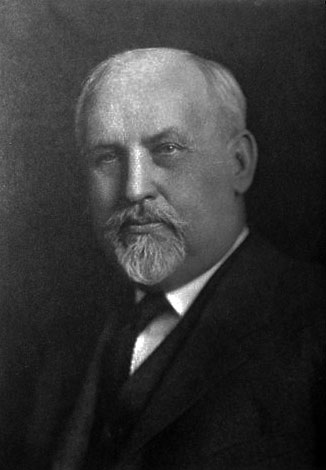

Ladd had studied the food problem in North Dakota and concluded that the state had been a “dumping-ground for the waste food products.” Ladd encouraged the North Dakota legislature to pass the Adulteration of Food Act in 1903. (See Image 3) The law covered only the foods processed in the state. Foods processed elsewhere and shipped into North Dakota were covered by federal law. (See Image 4) The federal Pure Food and Drug Act was not in effect until 1906. (See Document 6)

The state law took a heavy toll on Ladd. He later recalled that for two years after the law was passed, he “did not go to bed a single night without a libel suit or an injunction, or both, hanging over my head. . . .” Nevertheless, both state and federal judges gave Ladd a great deal of support. After Ladd became State Food Commissioner, he declared that food available through merchants in North Dakota had improved in quality. (See Image 5) Food labeling meant that consumers no longer purchased a package of ground pepper that actually contained ground coconut shells. (See Document 7)

Manufacturers were putting preservatives into processed food products with very little concern for the effect of the chemical on humans. In a test for the safety of nitrites added to flour to bleach it to a nice white color, the residue from the mix was liquefied and injected into rabbits. If the rabbit did not die immediately, the substance was considered safe.

Ladd’s work helped North Dakota farmers. North Dakota wheat produced a very white flour, but wheat grown elsewhere often produced a grayish flour. Using the Alsop Process, millers added nitrites to flour to lighten the color. Ladd and other pure food chemists believed that nitrites were an unsafe additive. Ladd testified on his findings in court. As a result, all flour treated by the Alsop process had to be labeled “bleached flour,” before it could be sold in North Dakota.

In 1916, Edwin Ladd was appointed to the position of president of North Dakota Agricultural College. By that time, he had gained a very favorable reputation among the people of the state for his work in protecting the food supply of North Dakota.

In 1920, Ladd, a Republican with the support of the Nonpartisan League, was elected to the U. S. Senate. He died in 1925 of kidney failure while still serving in the Senate. Governor Lynn Frazier described Ladd as “one of the foremost workers for pure-food legislation” and “a citizen . . . universally loved and respected.”

Document 7: Food Summarized by Years for 1641 Samples

|

|

Per cent Adulterated |

||||||

|

Food Type |

1902 |

1903 |

1904 |

1906 |

|||

|

Jellies, preserves, etc. |

100 |

30 |

48 |

18 |

|||

|

Catsups (ketchup) |

100 |

25 |

57 |

36 |

|||

|

Canned corn |

88 |

28 |

14 |

6 |

|||

|

Canned peas (American) |

50 |

38 |

4 |

0 |

|||

|

Tomatoes |

40 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|||

|

Lemon extract |

70 |

47 |

34 |

16 |

|||

Chart of Adulterated Foods. This chart summarizes Ladd’s studies of some foods over several years. Professor Ladd claimed that the North Dakota food laws and the federal Pure Food and Drug Law improved the sanitation and quality of foods. Adapted from: North Dakota Agricultural College Experiment Station Bulletin No. 69, 1906.

Why is this important? Edwin Ladd’s work as a chemist was important to both the state and the nation. He worked closely with Dr. Harvey W. Wiley of the U. S. Department of Agriculture in a campaign to get a Pure Food and Drug law passed in Congress. His success with the North Dakota Adulteration of Food law led to the passing of similar laws in other states. His popularity in the state resulted from his concern for the quality of food that ordinary North Dakotans ate. His work to curb the excesses of food processing corporations was in step with the issues brought forth by the Nonpartisan League. He became, through his commitment to his work, one of the most famous North Dakotans of his day.