The Mandan and Hidatsa (Gros Ventres) tribes signed the TreatyA treaty is an agreement between nations. The U.S. Constitution requires that all treaties be approved by the U. S. Senate. Indian tribes were considered “domestic dependent nations” according to a Supreme Court decision in 1831 (Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, 30 U.S. (5 Pet.) 1, 17.) As nations, Indian tribes engaged in negotiations with the United States over their land claims. For ceding (or giving up) most of the land where they had hunted, farmed, gathered plants, and worshiped for hundreds of years, Indians were allowed to keep small portions of their territory. In addition, they received cash and annuities, or goods, that were delivered to residents of the reservation. Sometimes these goods were listed specifically in the treaty. For instance, they might ask for medicine, food, and agricultural equipment.of Fort Laramie in 1851. The treaty required that they give up land and warfare. In exchange, they were to receive payments in the form of goods and supplies worth $50,000 per year. These annuities (payments) were to continue for 25 years.

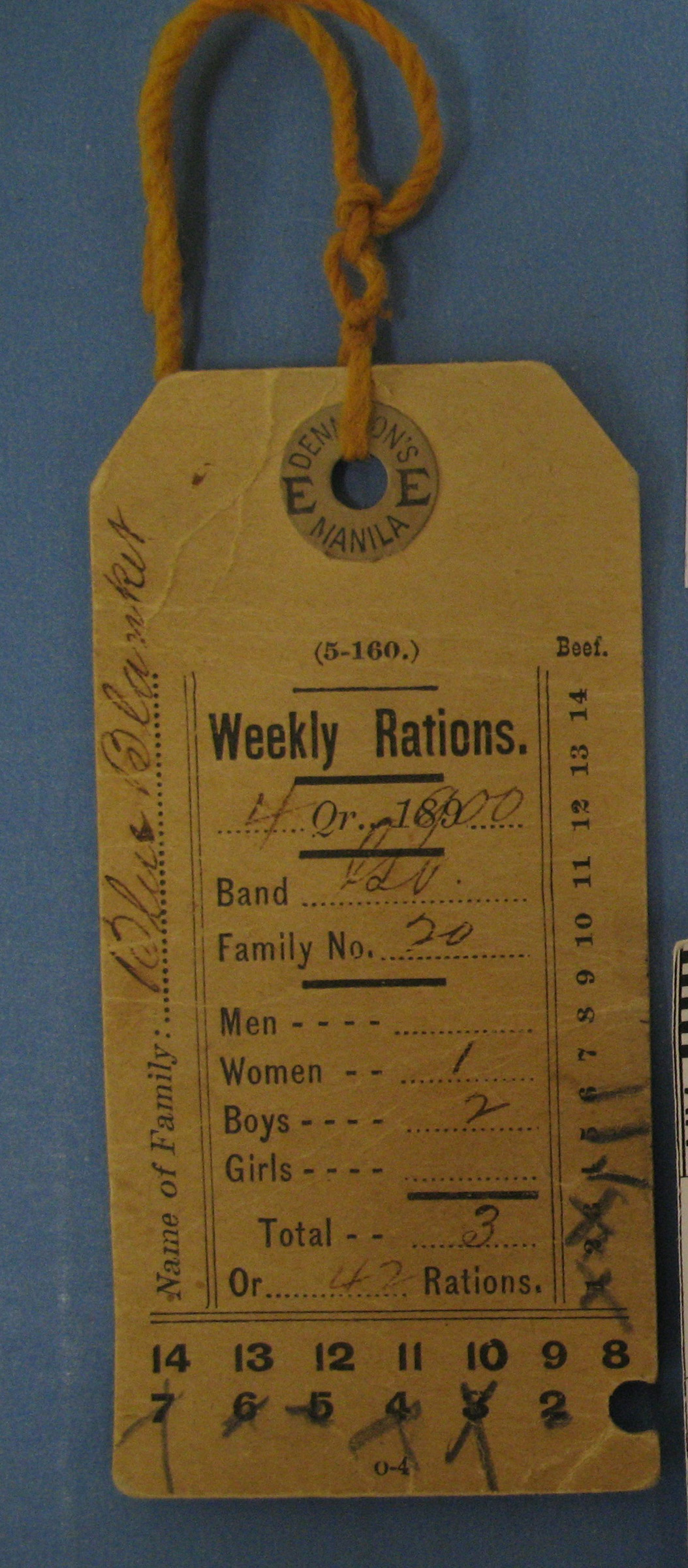

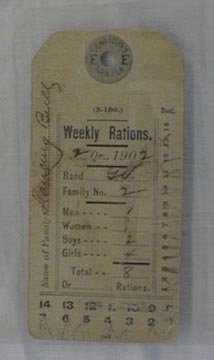

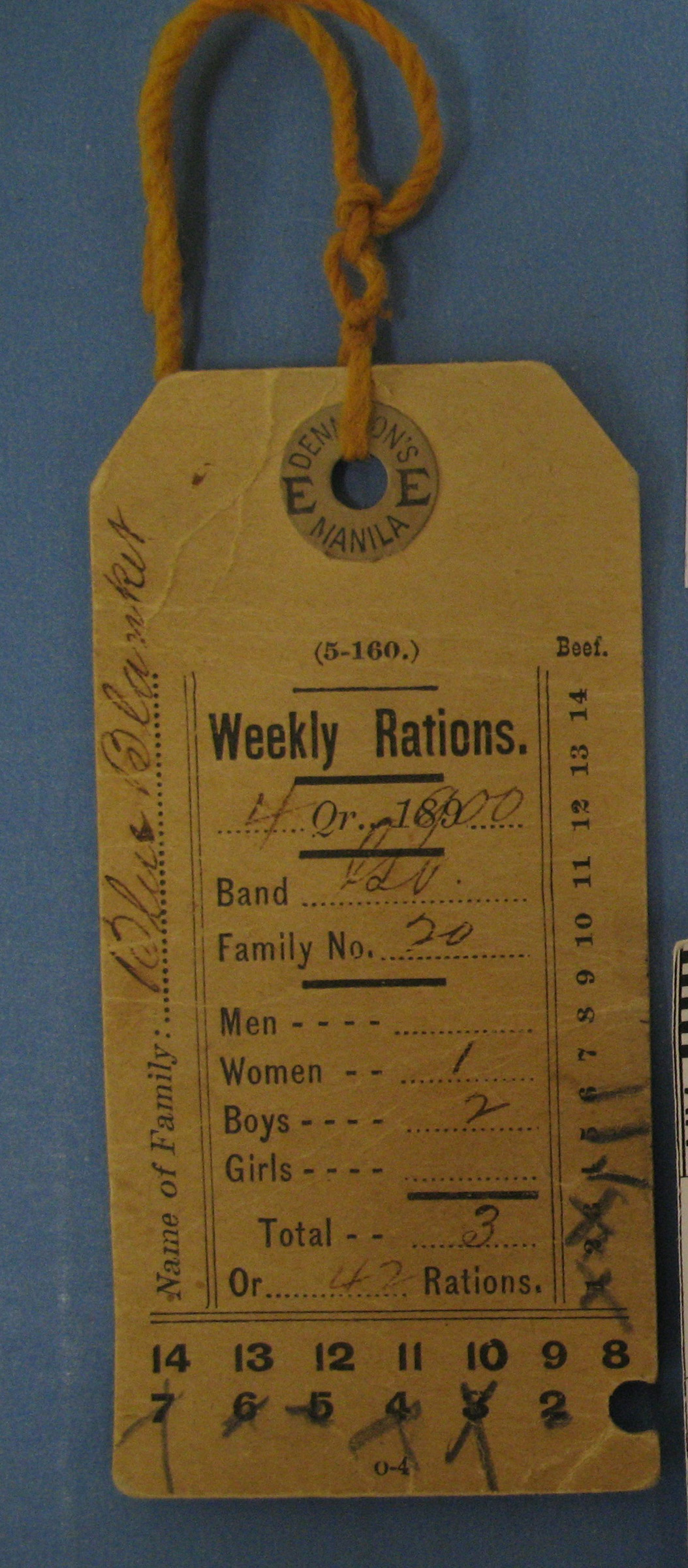

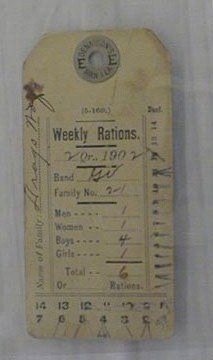

In the beginning, the annuity goods arrived by steamboat two times a year. A few years later, an agent was assigned to Fort Berthold, and he considered it his job to distribute the annuity goods. Each family received rations (or allowances) of food and clothing according to the number and age of people in the family. (See Image 7) A ration was seven pounds of beef, seven pounds of flour, four ounces of soap, four ounces of salt, and one pound of bacon. About 20 years later, the rations were reduced; a beef ration was only five pounds.

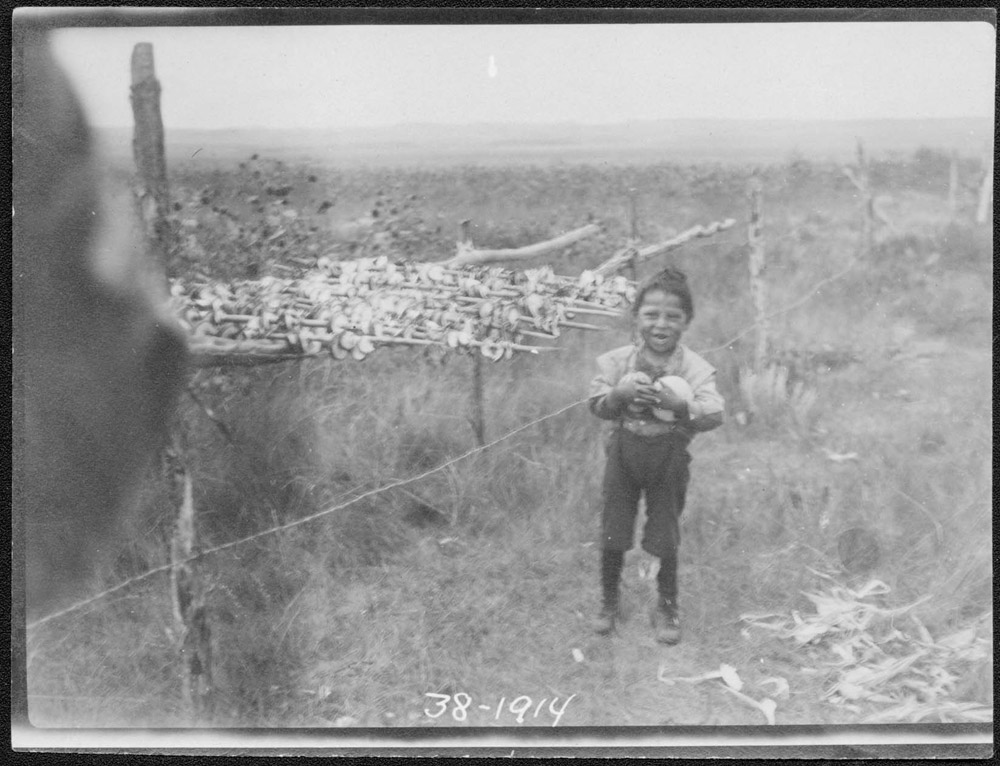

Over the years, the Mandans and Hidatsas signed other treaties. They gave up much of their land and accepted a reservation. Again, they were promised annuities in exchange for their land. As the buffalo disappeared from their land and it became impossible to huntYou might be thinking that if Indians could not hunt bison, they could hunt deer, antelope, and other big game animals. Well, they could, and they did. Wolf Chief (Document 1) mentioned hunting deer and antelope in his letter to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs. However, by 1900, the number of deer and antelope was reduced to a very small number. Too many hunters and ridiculously weak game laws took a big toll on wild game in North Dakota. Hunting regulations on reservations were different than state regulations, but wild game populations were so small that people rarely saw game animals in the early decades of the 20th century. for meat, they came to depend on rations to supplement food from their gardens. (See Document 1)

Document 1: Wolf Chief’s Letter

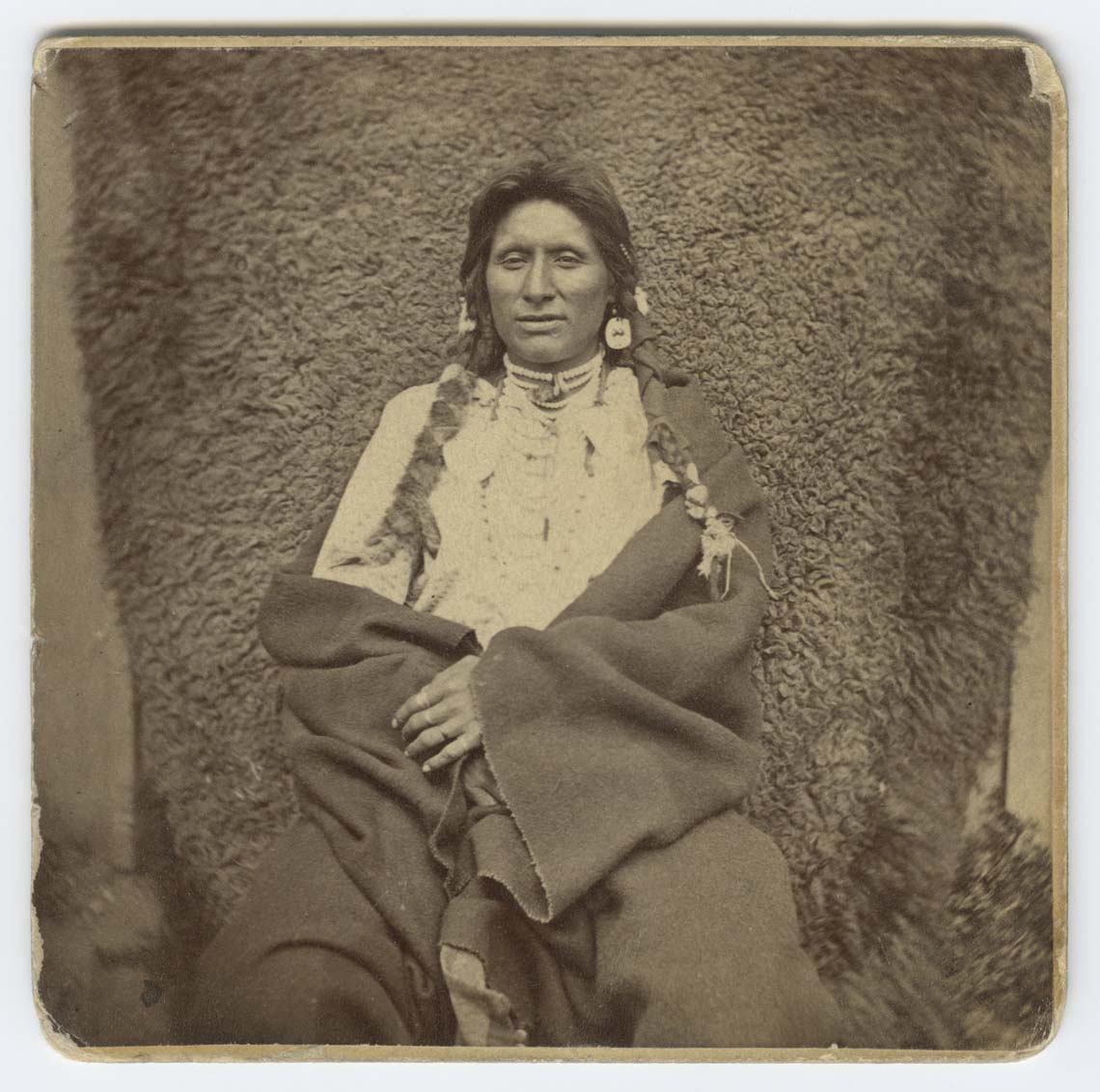

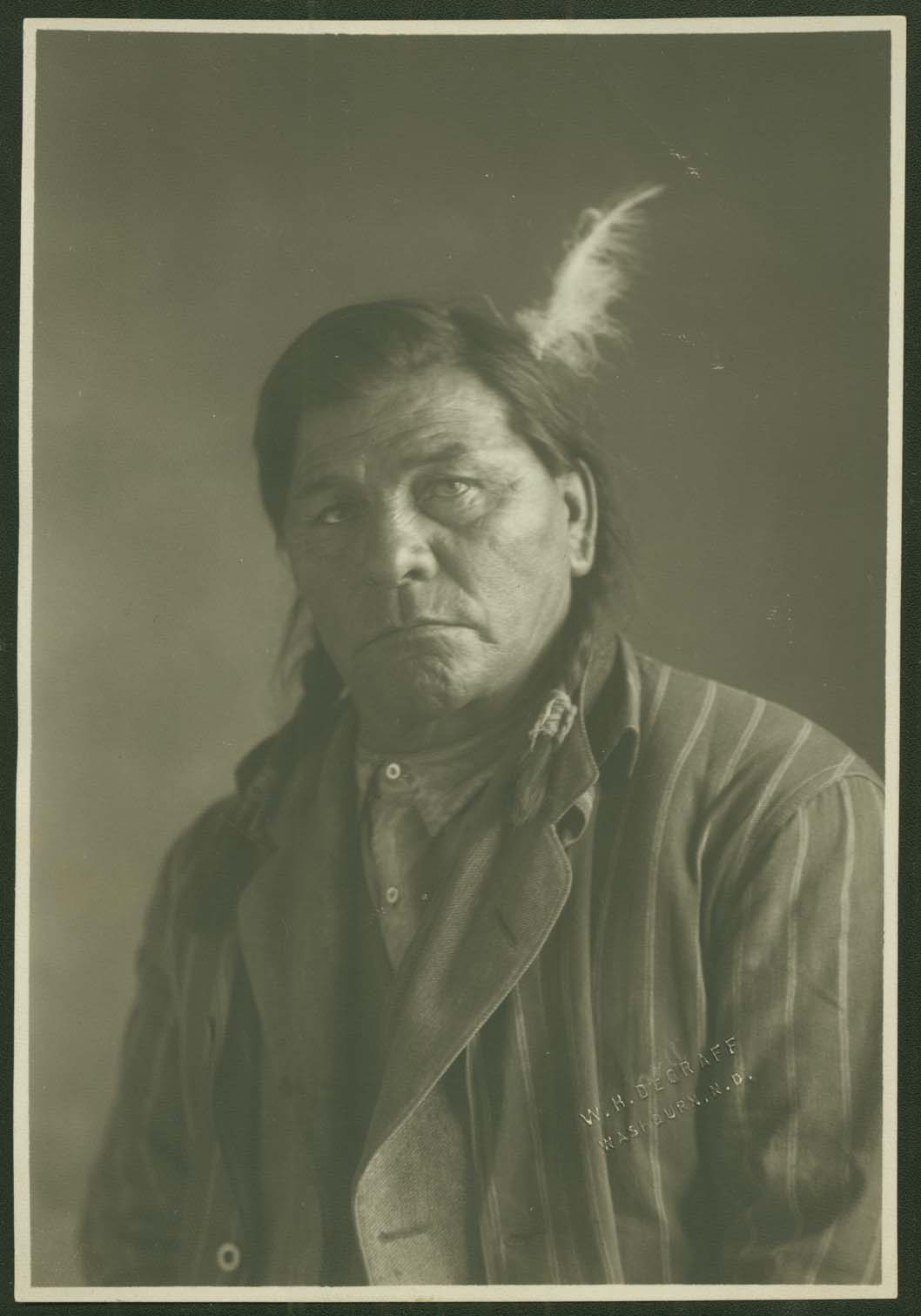

Wolf Chief was born to a Hidatsa family in 1849. (See Image 8) He grew up with his sister, Waheenee, also known as Buffalo Bird Woman. As he grew to manhood, the Hidatsas lived on the Fort Berthold Reservation. The Hidatsas (or Gros Ventres as they were then known) were encouraged to live in wood frame houses instead of earthlodges. Reservation agents instructed the people to find work other than hunting, trading, and gardening. Wolf Chief decided to open a small store. As a Native American living on his own reservation, he did not have to have a trader’s license to operate his store.

However, he did have to follow federal regulations. Regulations did not allow him to sell ammunition. The letter was written only two months after the Massacre at Wounded Knee and the death of Sitting Bull, the Lakota leader. Wolf Chief was trying to be very clear that the Mandans, Hidatsas, and Arikaras lived peacefully on their reservation.

Wolf Chief saw hunger on the reservation. Government rations did not supply enough food. Wild game meat would have been very welcome if the Hidatsas could buy ammunition for hunting. (See Image 9)

Fort Berthold Agency, N. D.

February 17th, 1891

Dear Great Father and

Gen. T. J. Morgan Commissioner of Indian Affairs

Washington, D. C.

My Dear Friends,

Dear Sir,

I have received your letter dated Jany 17th And I was very glad to hear that I can trade in Indian Country without license. But I am sorry that I can not sell any fixed ammunitions. I believe every body in this reservation wished to have me sell cartridges not that we want to fight anybody but because we use them in hunting. You need not be fraid of us. We are taking up White mans ways. We dont hunt all the time neither most the time, but we [do] some farming hay making, [selling] dry bones cutting wood and all that. but in such time as this when we can not plough, make hay sell wood and bones and [with] the rations cut down [reduced] we need some thing to make our living somehow then antelop, deer and other games we can hunt and make part of our livin.

I am sure that you have a very poor knowledge of the Indians in this reservation. If I take you to visit an Indian family of a husband, wife and child on Sunday evening next day after rations day we see now that he get fifteen pounds of flour and few ounces of each coffee and sugar for forteen day. Do you think they will not consume them till at the end of forteen days? We cannot, and no one can, you know that we can not get living in no way but hunting, and we depend upon rations but they are very little indeed. You know that you cannot live on 5 lbs of beef and flour for 14 days, and work every-day. I would not asked you this if we can find some [work] to make our living. Tak[e] Whites the ration all fair long as we can find some work to help along. Please consider the matter not in the interest of any White-men, but in the interest of the Indian of this reservation. I rather think that the section 31 applies only to the license traders.

Please I want to hear [from] you soon. Today we Mandan have come all together and we want you all Great Chief in Washington to help us. And the Washington All Big Chief Shall not be forgotten.

Please Very soon write me

Very truly you friends

Mr. Wolf C. Chief

[also signed by] Mandan, Crow Breast, Little Bear, Red Shield, Many Crow, Bear heart, not good, Short Bull, Running Wiles, Ded Drum, good Bunch, Charging Enemy, Bear Tail, Two Chief, White fingernail, Mandan Son Star.

The distribution of the annuities caused some problems. The reservation agent, an employee of the U. S. government, distributed the goods. This was not the traditional way of making gifts among the Mandans and Hidatsas. Before the Mandans and Hidatsas lived on a reservation, gifts were given by courageous hunters, thrifty and skilled women gardeners, or wealthy members of the tribe. The gifts were given as a way of making friends and bringing families close together. When the federal agent gave gifts, these traditions were not honored, and community ties were weakened.

Government agents knew that distribution of annuities was designed to break down traditions. That is what they wanted to do. Many government officials, reservation agents, and missionaries believed that Indians had to lose their old traditions before they could learn the culture of Anglo-Americans. The new culture included sending people to live on their own farms instead of a village. Dancing, membership in societies, and traditional religious ceremonies were outlawed. Participation could be punished by spending time in jail.

The Mandans and Hidatsas, however, tried to incorporate traditions with the new ways. On the day that annuities arrived, members of these tribes gathered together. (See Image 10) This was a time for renewing friendships. At the distribution, they sat in circles as they did in a traditional ceremony. They maintained, as much as possible, some cultural traditions in the face of change.

Why is this important? Annuities and rations were a legitimate payment for loss of hunting land, buffalo, and the important traditions of the Mandans and Hidatsas. Many of their traditions were linked to their hunting and gardening economies. When those were changed or destroyed, the people of Fort Berthold came to depend on rations for their food supply. The federal agent also taught them to raise livestock and crops and to sell their products in nearby markets. However, when drought, grasshoppers, or disease caused a crop failure, they depended on rations to make up the difference.

The Families

After the Mandans, Hidatsas, and Arikaras signed a treaty in which they gave up some of their land, they were to receive payments for that land in the form of annuities or supplies.Annuities included food, farm equipment, fabric, blankets, cooking pots, and other things they needed to live on a reservation. Among these things, food was the most important item. They no longer lived in villages where they would garden along the low banks of the river. They could not leave the reservation to hunt bison and other large game animals. They no longer had an effective system of sharing food that protected the poor, elderly, ill, and disabled from starvation. Annuities were essential part of the transition to reservation life.

The distribution of rations was recorded for each family on a “ticket.” The agent either punched a number or crossed it off as a family received its rations. Each family was to receive a fixed amount of beef, flour, and other goods each quarter (or three month period) based on the number of adults and children in the household.Using the ration tickets and information available on the Indian Census (available at Ancestry.com) we can learn a little about each of these families.

Dancing Bull, a Hidatsa, was born in 1851. (See Image 11) In 1902, he was 50 years old and worked as a farmer. His wife was Different Snake, age 42. They had been married for thirteen years. Different Snake had given birth to seven children; only four survived. The three oldest children, Julie (age 12), Fannie (age 8), and Jackson (age 6) attended school. The youngest, Walking Bull, at four years old, was still too young for school. Because these children were counted on the ration ticket, it is likely that they attended the Day School, rather than a distant boarding school. Dancing Bull’s household also included his mother Long Hair, his mother-in-law Walks Along Good, and his niece Mary Rabbit Head (age 20). The census tells us that Dancing Bull and Different Snake could not read, write, or speak English, but their children were learning English in school. (See Image 12)

Blue Blanket was a divorced woman with two sons. She had borne six children, but only two survived.She was 35 years old in 1900. Though the ration ticket says that she was Hidatsa, the census says that her mother was Mandan and her father was Sioux. She should have been recorded as a Mandan woman, but the federal agent might have called her Hidatsa if her husband had been Hidatsa. Blue Blanket’s oldest son was Norman Yellow Eagle who was eight. He attended school ten months of the year. (See Image 13)

Drags Wolf and his wife, Prairie Dog Woman, had four sons and two daughters. (See Image 14) The three oldest children, Edward, Truie, and James Drags Wolf had been assigned their father’s name as their last name when they started school. (See Image 15) Their three younger siblings, Rolls in Clay, Rolls Medicine, and Corn Silk did not have a last name listed on the census. Like their ancestors, they had a special name that identified them; no last name was necessary. Of course, their names were written in the English translation in the census, but it is unlikely that their families called them by these English names. Drags Wolf and Prairie Dog Woman had been married for 13 years. Drags Wolf was a farmer.The census taker did not name an occupation for Prairie Dog Woman. (See Image 16)

Why is this important? The people of Fort Berthold retained their dignity in spite of federal control of reservation life in that time period. By reading and analyzing the federal ration records and expanding our knowledge with photographs and other sources, we see people in families with growing children. We know they worked to support their families at farming and other jobs. The people of Fort Berthold found a balance between the traditional lives of their parents and the future that belonged to their children. The ration tickets are one piece of evidence we use to reconstruct the lives of people who lived through this important transitional period for American Indians.