On April 6, 1805, Meriwether Lewis and William Clark were organizing their boats and men for the journey up the Missouri River. They had spent the winter at Fort Mandan near the villages of the Mandans and Hidatsas. Some of the men of the expedition would be taking the keelboat packed with supplies and collected materials back to St. Louis. Both departures were delayed when a messenger arrived bringing word that a delegation of ArikarasToday, the Arikaras are reclaiming their traditional word for themselves: Sahnish. When you read about the Arikaras historically, you will see the words Arikara, Ricaree, Ric Ree, or Rees. In this text, we use the term Arikara because it is consistent with many of the historic records of this time period. were on their way to the Mandan villages..

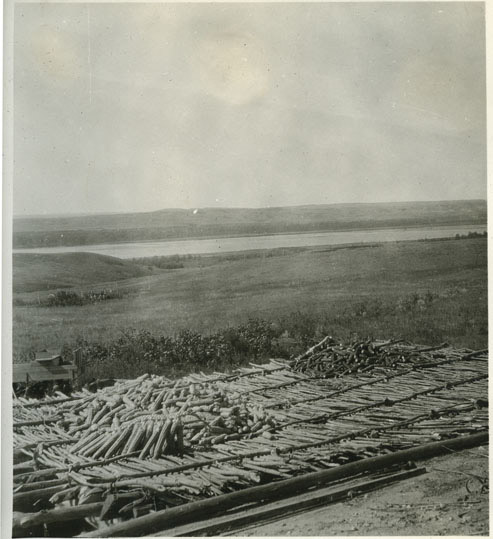

The Arikaras were considering moving their villages to a location near the Mandans and Hidatsas. (See Image 7.) They planned to speak to the Mandans and Hidatsas to find out if they would be welcome and if the three tribes might form an alliance that would provide more protection for all. The Arikaras also asked Lewis and Clark if they could send one of their chiefs back to their main village (in present-day South Dakota) on the keelboat. (See Document 4.)

Document 4. Lewis and Clark Journals at Fort Mandan

Arikaras told Lewis and Clark that the tribe was thinking of re-locating near the Mandans and Arikaras. They had a letter from the trader Tabeau who indicated that some Arikara chiefs (including Ankedoucharo) wanted to travel to Washington, D.C. to meet President Jefferson. Lewis and Clark made arrangements for this journey before they went on. More than one year later as they returned to St. Louis, Lewis and Clark met Joseph Gravelines, the interpreter, on the Missouri River. Gravelines was bringing news about the death of Ankedoucharo to the Arikara village.

[Clark]

7th of April Satturday 1805

a windey day, The Interpreter we Sent to the Villages returned with Chief of the Ricara's & 3 men of that nation this Chief informed us that he was Sent by his nation to Know the despositions of the nations in this neighbourhood in respect to the recara's Settleing near them, that he had not yet made those arrangements, he request that we would Speek to the Assinniboins, & Crow Inds. in their favour, that they wished to follow our directions and be at peace with all, he viewed all nations in this quarter well disposed except the Sioux. The wish of those recaras appears to be a junction with the Mandans & Minetarras in a Defensive war with the Sioux who rob them of . . . property in Such a manner that they Cannot live near them any longer. I told this Chief we were glad to See him, and we viewed his nation as the Dutifull Children of a Great father who would extend his protection to all those who would open their ears to his good advice, we had already Spoken to the Assinniboins, and Should Speeke to the Crow Indians if we Should See them &c. as to the Sioux their Great father would not let them have any more good Guns &c. would take Care to [enact] Such measurs as would provent those Sioux from Murding and taking the property from his dutyfull red Children &c.— we gave him a certificate of his good Conduct & a Small Medal, a Carrot of Tobacco and a String of Wompom [beads] — he requested that one of his men who was lame might decend in the boat to their nation and returned to the Mandans well Satisfied—

This Cheif delivered us a letter from Mr. Taboe. informing us of the wish of the Grand Chiefs of the Ricarras to visit their Great father and requesting the privolage of put'g on board the boat 3000 w of Skins &c. & adding 4 hands and himself to the party. this preposeal we Shall agree to, as that addition will make the party in the boat 15 Strong and more able to defend themselves from the Seoux &c.

Source: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/8419/8419-h/8419-h.htm

The Arikaras had brought with them a letter written by Mr. Tabeau, a trader who lived at the Arikara village. The trader asked permission to send furs down river on the keelboat. He also stated that several Arikara chiefs wanted to travel to Washington to meet President Jefferson. A few days later, the respected chief Ankedoucharo boarded the keelboat. After many delays, the delegation of chiefs from several Missouri River tribes finally arrived in Washington, D.C. in February, 1806.

Ankedoucharo and the other chiefs met with President Jefferson. They spent a couple of months touring Washington, Philadelphia, Boston, and New York. AnkedoucharoAnkedoucharo is the name that was used to identify an Arikara man more properly called Piahito. Piahito, or Eagle Feathers, was a leading man of the Arikaras. Ankedoucharo means “village chief,” and that is the name that was used on his journey to eastern cities. Because the historic record usually refers to him as Ankedoucharo, we will use that name in this text.

By all accounts, Ankedoucharo was an intelligent, well-mannered man who challenged the idea popular at the time that all Indians were primitive savages. He spoke 11 American Indian languages in addition to hand sign. He took with him to Washington a map that he had painted on a tanned bison hide showing the Missouri and Platte Rivers, tributary streams, villages, and mountains. The map also identified “four mines of Platina [silver], several of copper, and a volcano.” Newspaper Editor Samuel Mitchill wrote that Ankedoucharo’s map was “pleasing proof of the Geographical Knowledge of these self-educated people.” Ankedoucharo won respect and friendship during his tour of the states. We don’t know what caused his death made a strongly favorable impression on the people he met.

On April 7, 1806, about one year after leaving home, Ankedoucharo died and was buried in Richmond, Virginia. President Jefferson was informed and quickly set about composing a letter of condolence to the Arikara people. Joseph Gravelines, an interpreter who had traveled to Fort Mandan with Lewis and Clark, was sent to deliver the letter to the Arikaras along with some gifts. (See Document 5.) The Arikaras were angry about the death of the leader. Jefferson’s letter did little to sooth them.

Document 5. President Jefferson’s Letter to the Arikaras

In April, 1806, President Thomas Jefferson wrote a letter to the Arikaras of Ankedoucharo’s village. He asked interpreter Joseph Gravelines to deliver the letter and some gifts to the Arikaras. Jefferson also asked Gravelines to instruct the Arikaras in agriculture. Jefferson did not seem to understand that the Arikaras were already agricultural experts. Gravelines was unable to reach the Arikara village until September 1806.

He (Chief Ankedoucharo) consented to go towards the sea as far as Baltimore and Philadelphia. . . . The chief found nothing but kindness and good will wherever he went, but on his return to Washington he became ill. Everything we could do to help him was done but it pleased the Great Spirit to take him from among us. We buried him among our own deceased friends and relations. We shed many tears over his grave.

The death of Ankedoucharo began a period of troubles between the United States and the Arikaras. The Arikaras felt that Ankedoucharo’s death had not been properly explained. They remained distrustful of the government and of fur traders for many more years. In 1823, bad feelings resulted in war.

On June 2, 1823, the Arikaras attacked boats belonging to General William Ashley. Ashley was trying to establish a huge trading and trapping operation in the Rocky Mountains and depended upon the Missouri River as a transportation route. When Ashley’s boats reached the Arikara village near the Grand River (in present-day South Dakota), the Arikaras attacked, using guns Ashley had given them. Twenty of Ashley’s men died and nine were wounded. The Arikaras took Ashley’s trade goods from the boats.

Government officials were angry and set out to punish the Arikaras. Though the Arikaras had been occasionally allied with Teton Dakotas, the Tetons decided to join the Army in this fight. The U. S. Army reached the Arikara village on the lower Missouri River with soldiers, cannons, and 800 Teton warriors in August, 1823. The Tetons went first into battle against the Arikaras, but the Tetons doubted that the Army would win. They took corn from the Arikaras’ fields and then refused to fight more for an Army they considered weak.

The next day, the army attacked sending cannonballs flying into the fortified village. The Arikaras discussed a truce, but during the night the entire population of the village slipped away with their horses, dogs, and household goods.

Hostilities did not end, however. Bad feelings remained between the Arikaras and government agents and fur traders for many more years. It was not until 1837, when the Arikaras, badly weakened by the smallpox epidemic, settled into a village near Fort Clark. They were now prepared for a more peaceful relationship with the government. A few years later, Arikara men became trusted scouts for the US Army.

Why is this important? The Arikaras had been involved in the Teton Dakota trade network, but this was often not to their advantage. Considering those circumstances, the Arikaras might have welcomed trade with Americans as promised by Lewis and Clark. However, once they learned of the unexplained death of Ankedoucharo in a strange place, they could not offer their trust and loyalty to the United States.