What we know about dinosaurs, mastodons, and petrified forests depends on the work and study of paleontologists. The study of paleontology goes back more than 200 years. In that time, scientists have learned much about life in the very distant past.

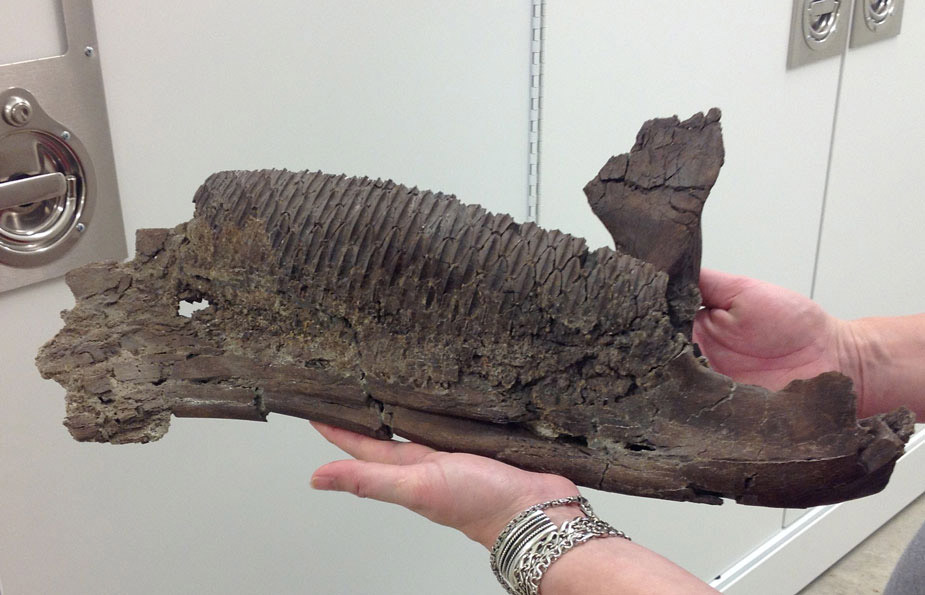

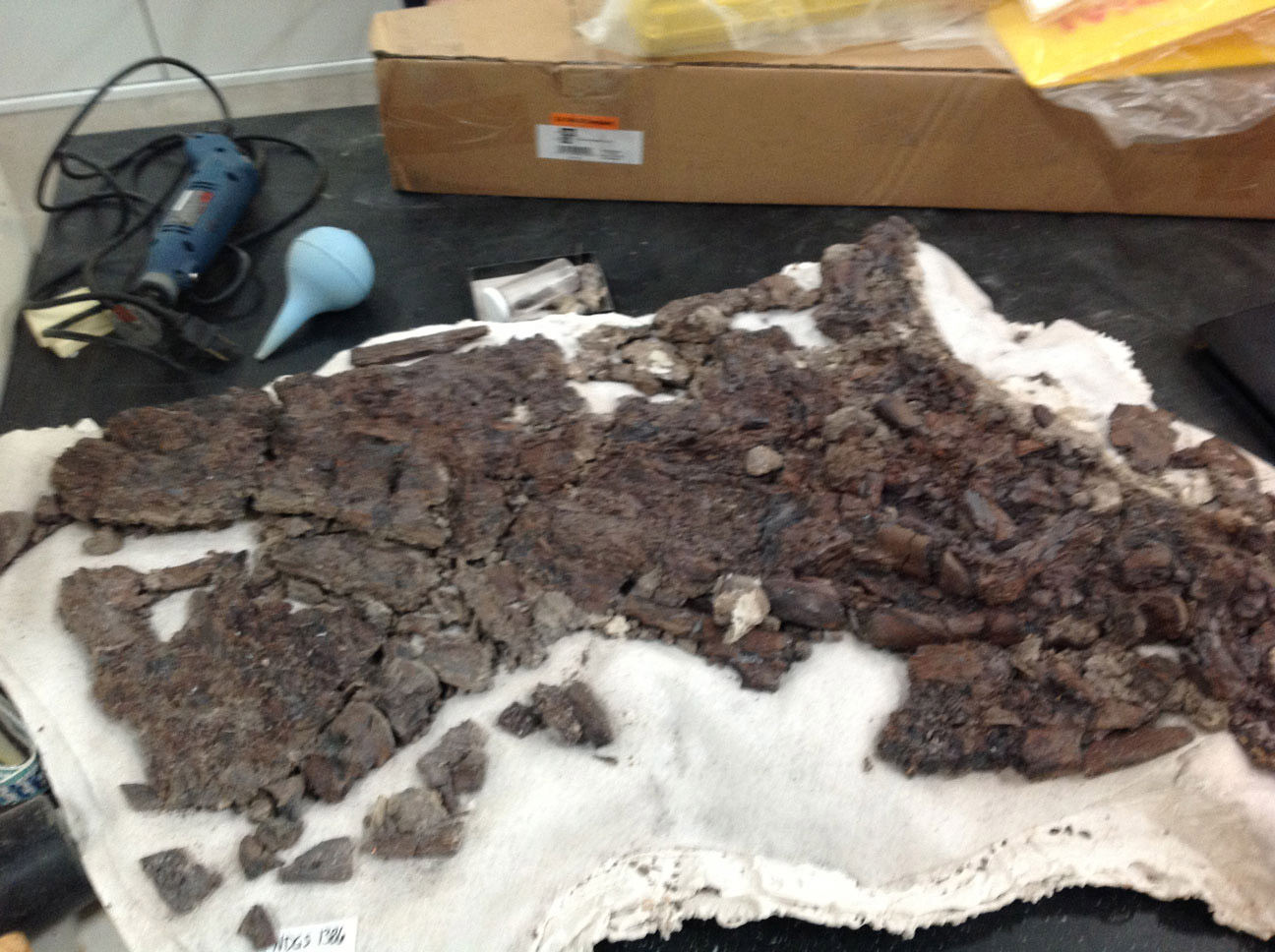

The State Historical Society of North Dakota houses the paleontology laboratory of the North Dakota Geological Survey. The storage cabinets in the laboratory hold thousands (See Image 28.) of pieces of bones and teeth and pieces of rock with fossilized plants and animals captured in them. (See Image 29.)

When someone finds a set of bones or a piece of bone, paleontologists carefully note the exact location and the formation (geological layer) it has been found in.Caution: Don’t try this at home! You can learn a lot about paleontology by studying books and participating in public digs (dmr.nd.gov/ndfossil). However, excavating an important fossil is work that should be done by experienced professionals. If you come across a nice fossil, contact the North Dakota Geological Survey. The formation will help to identify the fossil because certain animals are associated with particular time periods. If the fossil is fragile, the bones will be covered in a “jacket” of Plaster of Paris to protect the bones and to make sure that each bone remains in the same place in relation to the rest of the bones. (See Image 30.)

Once the fossil has been excavated from the rocky formation where the animal died millions of years ago, it goes to a paleontology laboratory where it is cleaned and identified. Paleontologists examine the bones for identifying parts such as spinal processes which are bony points that stick out from the main part of a bone. (See Image 31.) They examine teeth to see if the animal was an herbivore with broad or flat teeth for chewing plants or a carnivore with sharp teeth or serrated edges. Once they have evaluated the fossils for all identifying characteristics, they might be able to name the animal the fossil came from. However, if the fossil does not have strong identifying characteristics, it might be difficult to identify it.

In North Dakota, certain fossilized animals are fairly common. Fossilized parts of Edmontosaurus and Triceratops are relatively common, while Tyrannosaurus rex is pretty rare. There are fewer examples of animals of the Oligocene Epoch. It was a period of high erosion and few remains of animals were able to withstand the forces of erosion.

Because the fossils are fragile and a fossilized skeleton might be incomplete, one of the tasks of paleontologists might be to reconstruct fossils for display. (See Image 32.) The paleontologist may repair the fossil or replace it with a copy. There areThe paleontologist who makes displays at the Paleontology Lab in the North Dakota Heritage Center is Becky Barnes. She uses her education and interests in anatomy, paleontology, art, and ceramics to make casts and sculptures of ancient fossils. She studies fossilized bones in the collection and pictures of fossils in books to determine the exact shape of the fossils. She carves foam to make sculptures of fossils or makes silicone molds to produce copies of fossils. several possible ways to present a fossil for display. The parts of the fossil that are sturdy enough to be on display in a museum might be joined with artificial parts that were sculpted by a skilled paleontologist. Sometimes fragile bones are encased in material to make a mold from which a perfect copy is made. Another method is to sculpt a new bone from foam or other materials. These sculptures and casts are lightweight and can be displayed without damaging the original fossil. (See Image 33.)

Why is this important? When we enter a museum where fossils of ancient animals are displayed, we would love to see the actual bones of a real dinosaur. However, the problems of display include the difficulty of supporting the weight of a fossilized dinosaur, the possibility of damage to a rare fossil, and the common problem of missing parts. Paleontologists would like you to enter a museum display to learn more about the animals and plants that inhabited Earth at different times. From those displays you can learn more about how the Earth has changed over the past 500 million years.