For many North Dakotans, the potential for developing irrigation was the key issue in damming the Missouri River. The original plan for irrigation met some obstacles. Missouri River water was supposed to be sent through canals to irrigate farm land in northwestern North Dakota. However, the subsoil in the northwestern part of the state was composed of dense glacial material that was unfit for irrigation. The Bureau of Reclamation had to come up with a new plan.

The plan, called the Garrison Diversion, was submitted in 1957. North Dakota farmers were told that irrigation would increase farm income by a total of $55 million per year, increase trade statewide by $144 million each year, and bring 95,000 more people to the state. Everyone would benefit according to the estimates of the Bureau of Reclamation.

Image 6: The McClusky Canal was the final piece of the Pick-Sloan project. The canal was supposed to distribute irrigation water from Lake Sakakawea to one million acres of farm land, but the project was too expensive and impractical. Many farmers resented having the canal cut through their farms, often cutting off direct access from one part of the farm to another. Today, the canal will be part of a system that transports Missouri River water to the Red River Valley. In this photograph taken in the 1970s, Pearl Wall herds cattle with canal construction in the background. SHSND 21081-08.

There was, of course, one small concern. Engineers estimated that the Diversion would be very expensive. The Bureau’s plan called for 6,773 miles of canals extending from a few main canals. The system would be built over 60 years. There would also be eight reservoirs, dozens of urban water systems, pumping stations keep the water moving, and 9,000 miles of drains. The total estimated cost was $529 million dollars. This estimate did not account for inflationWhat is inflation and how does it work? Inflation happens when the cost of goods (things like food or cars) and services (such as a mechanic’s labor charge) increase. In the U.S. economy, we can expect some inflation. An economy that has no inflation is considered stagnant which is not desirable. Deflation (which is usually called depression) happens when the price of goods and services falls. Inflation can be unhealthy for the economy if the cost of goods and services increases much faster than the value of the dollar. If we account for inflation, the Bureau’s estimate of $529 million in 1960 would be $4.05 billion today. over the 60 year period of development.

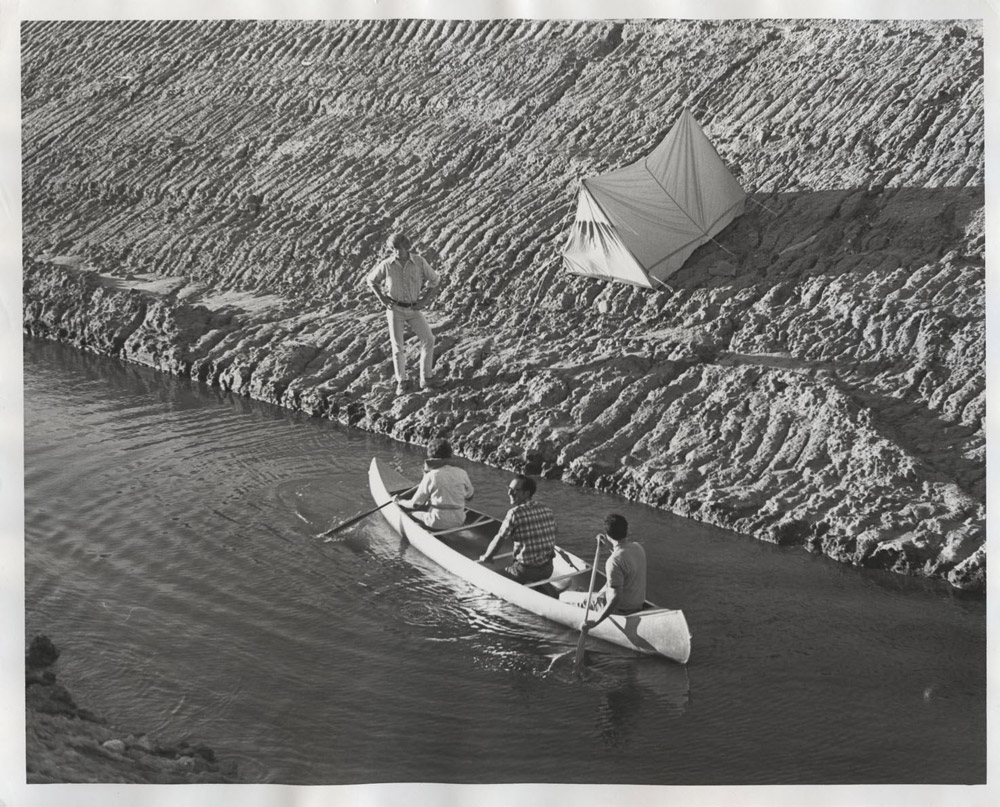

Image 7: Recreation was part of the plan for the McCluskey Canal. This group explores the possibility of canoeing and camping on the canal in the 1970s. Few people found the canal an appealing place for recreation. SHSND 21081-08.

In previous projects, the Bureau of Reclamation asked the water users (farmers) to pay for the costs of construction over many years. Irrigation on dry land could increase crop production three times over, but farmers resented the high price. The Bureau also planned to bill cities for their water usage, and some of the costs of construction would be paid by power generating plants (whose customers would have to come up with the payments.)

Under the Garrison Diversion Plan, only a small portion of North Dakota’s farm land would have access to irrigation water. The plan at the peak of operation would irrigate about one million acres, or about five percent of North Dakota’s crop land. Soil tests, however, indicated that there were other locations in the state where the soil was unsuitable for irrigation.

Image 8: The McClusky Canal can irrigate about 75,000 acres of farm land. Though irrigation turned out to be a disappointing part of the Pick-Sloan project, the McClusky canal has also transported water for city and industrial use. SHSND 2013-P-017-0586

Not only was the cost of the irrigation plan high compared to the potential benefits, but fewer acres were planted for crops during the 1950s. A federal farm program called Soil Bank encouraged farmers to “rest” their cropland. North Dakota farmers put about three million acres into Soil Bank. In addition, economists believed that if crop prices rose a little bit, or if new agricultural methods increased crop production, irrigation would not be necessary. On close examination, the Bureau of Reclamation’s vision for irrigation of crops in North Dakota did not add up to a great improvement in farm production.

The project stalled while all of the problems were discussed. In 1965, Congress finally authorized a new development--the Garrison Diversion Unit. Under the new plan, the Diversion would develop municipal, rural, and industrial water supplies, fish and wildlife habitats, and recreation. The Diversion would also irrigate up to 250,000 acres.

Construction began on this new project in 1968. (See Image 6.) The McClusky canal was built to carry water away from Lake Sakakawea. However, in the mid-1980s, new environmental and economic concerns arose. The plan was revised again. The new version of the project placed a priority on drinking water and industrial use, environmental protections, and recreation. (See Image 7.) The cost rose to $1.2 billion.

In 1990, President George H. W. Bush declined to renew funding for the Garrison Diversion Unit. In 2000, the Dakota Water Resources Act (yet another name for Garrison Diversion) revived the plan with more emphasis on urban, rural, and industrial water use and environmental protections. (See Image 8.) Today, the Garrison Diversion and the state of North Dakota is preparing a project that will deliver Missouri River Water to the Red River Valley. This water supply will allow for greater population and industrial growth in Fargo, Grand Forks, and other cities in the eastern part of the state.

Why is this important? The Garrison Diversion did not keep the promises of the Pick-Sloan project to North Dakotans. On the other hand, the people of North Dakota did not whole-heartedly support the plan. In the past, North Dakotans had adjusted their economies and expectations to the resources available to them. North Dakotans were not prepared for the Bureau’s big vision and the high price was too much. More than 50 years after the plan was first presented, people are still debating its value and practicality.

However, water needs in North Dakota have changed a great deal in recent years. Urban water use and the need for water in the oil fields are placing new demands on Missouri River water. The conversation that started in 1957 and construction of some canals will continue even though the specific details about water needs will change from time to time.