News

• Disaster: The Spring of 1997

• Focus on Youth in Indian Country

• The ARC Lawsuit of 1982

• Trouble in Medina

• Recent Immigration

• Problem of Outmigration

• Centennial: Party on the Prairie

• Abortion Rights

• Completing Interstate Highways

Disaster: The Spring of 1997

by Barbara Handy-Marchello

The fall of 1996 began with a warning: early snows caused farmers and ranchers to start feeding hay to cattle a month early. Three blizzards struck the state in November and December. By April, the blizzard count had grown to eight. The last blizzard, named Hannah by the Grand Forks Herald, was the worst. It blanketed the state as the Red River (and other rivers) left its banks and threatened the cities and farms.

farms, roads, and much of the city of Grand Forks. N.D. Department of Emergency Services

fire trucks through deep water to get to the scene of the fires, but water pressure in the hydrants was too low to put the fires out.

N.D. Department of Emergency Services

The furnace, air-conditioning units, hot water heaters, and electrical boxes were destroyed by the flood waters. SHSND 2001-P-012-012

It was an unusually harsh winter with severely cold temperatures that caused the city water tank in Elgin to freeze and heavy snows to break down a portion of the Valley City Winter Show building. By January, snow-clogged roads and extraordinary need for feed made it difficult for farmers to feed cattle. More than 20,000 head of cattle, horses, and sheep died in January and February. Dairy farmers, unable to get their milk to a processing plant, dumped 500,000 pounds of milk between January 10 and January 19. To aid the Highway Department, the North Dakota National Guard was employed in clearing snow from highways and country roads. The state began to prepare for widespread flooding with warmer spring temperatures.

In March, the state Emergency Management office, the governor’s office, National Guard, Department of Transportation, and many other agencies as well as private organizations such as the Red Cross and Salvation Army coordinated efforts to prepare for floods. The National Guard built a sandbagging machine that could fill 1,600 to 2,000 sandbags per hour. By the end of March, floodwaters rose rapidly in several counties along the Knife, Cannonball, and Heart Rivers.

Both river flooding and overland flooding affected towns, farms, and highways in early April. Interstate Highway 94 was closed between Casselton and Fargo on April 2. Cities on the Red River reinforced dikes along the river with sandbags. Grand Forks residents noted that the dikes felt “spongy” as they became saturated with melting snow and rising river waters.

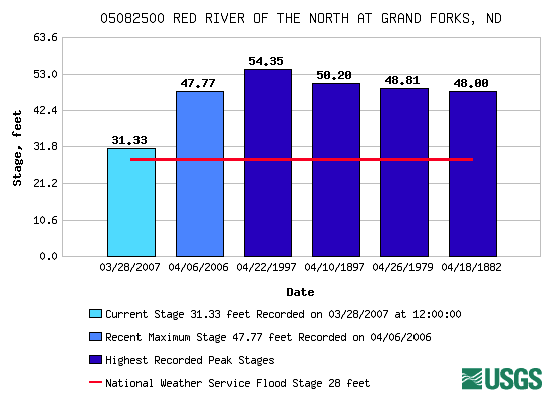

On April 4, the last blizzard struck. Snowfall ranged between 10 and 24 inches across the state adding more than two inches of moisture to already saturated ground and swollen rivers. More than 4,300 power poles and hundreds of electrical transmission towers went down. Thirty thousand homes lost electricity. Some of these homes needed power to run sump pumps and heating systems. Freezing rain and heavy snow broke radio and television towers limiting access to emergency information. People were forced from their homes by lack of electricity and rising flood waters. On April 6, President Bill Clinton issued a Presidential Major Disaster Declaration for the state and the Red River rose to record-breaking levels.

By mid-April, ranchers had assessed their losses. More than 90,000 head of cattle died in the April blizzard. It was calving season for many. They brought calves into their kitchens and living rooms. They dried the calves with hair dryers and wrapped them in warm blankets hoping to save a few. Ranchers cried as they watched their cattle flounder and die in the deep snow. However, as temperatures rose, the state with the help of the National Guard had to work quickly to remove the carcasses of the dead animals to prevent contamination of water sources.

On April 18, evacuation began in Grand Forks. The next day, the city asked residents to leave the city voluntarily as the dikes began to fail. Evacuation centers were set up at the Grand Forks Air Force Base, Mayville, Valley City, and Devils Lake. A mandatory evacuation order was issued on April 20. More than 50,000 people evacuated Grand Forks and East Grand Forks, Minnesota. The city water plant failed and natural gas and electricity services were terminated in much of the city. The university closed early and the lower floors of Central High School filled with water.

Pets could not go to the shelters and were often left behind. Later, after residents were safe, patrols re-entered the city in boats to locate houses with “DOG” or “CAT” signs on the windows. Pets were soon re-united with owners.

On April 19, the flood disaster was compounded by fire. Three city blocks in downtown Grand Forks burned even though four feet of flood waters swirled in the streets of Grand Forks. Fire trucks struggled through flood waters to get to the burning buildings.

By late April, the flood had crested and flood waters began to drop. Fargo began its clean-up operations. The city of Grand Forks faced massive restoration projects. When people were allowed to return to the city, they still had no running water or electricity. Portable toilets were set up in neighborhoods and people stood in line to use them. Electricity was slowly restored to neighborhoods after people replaced electrical boxes, furnaces, and hot water heaters that had been ruined by flood waters that filled basements.

The flat Red River Valley has always been prone to flooding. The 1997 flood mimicked the 1897 flood, but flooding was very frequent in the 1990s and 2000s and the population was much larger. Since 1997, Fargo has faced two more severe, record-setting floods. Both Fargo and Grand Forks have implemented improved flood control systems. Both cities are better prepared now to deal with high water on the unpredictable Red River.

...

Barbara Handy-Marchello is retired from the University of North Dakota History Department. She currently works for the North Dakota Studies program at the State Historical Society of North Dakota.

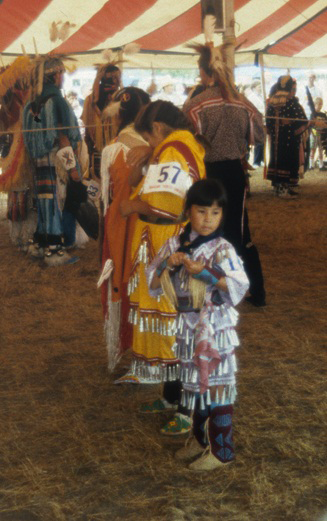

Focus On Youth In Indian Country

By Dakota Goodhouse

The last time a president of the United States met with members of the Lakota (Lakȟóta) Sioux tribe for a cultural exchange was in 1927 when President Calvin Coolidge met the Lakȟóta at Fort Yates on the Standing Rock Reservation. At that time, Coolidge was gifted with the name Matȟó Čhuwíksuya (Bear Rib), in honor of one of the great Huŋkphápȟa Lakȟóta leaders.

Standing Rock Tribal Chairman Dave Archambault (l) and Nicole Archambault (r) at Cannon Ball.

Tom Stromme photo, courtesy Bismarck Tribune

these who had participated in the powwow at Cannon Ball. President Obama is only the third sitting president

to visit an Indian reservation. Tom Stromme photo, courtesy Bismarck Tribune

Eighty-seven years later, on June 13, 2014, President Barack Obama and First Lady Michelle Obama visited Standing Rock Sioux Indian Reservation. Standing Rock Tribal Chairman Dave Archambault II credits former Chairman Charles Murphy for working with the White House Chief of Staff Pete Rouse to arrange the visit.

When the President’s helicopter landed in Cannonball, his first order of business was to meet with tribal youth for a roundtable discussion about the many challenges of growing up on the reservation. The topics of discussion ranged from poverty to homelessness. “The worst is over,” said the President, and remarked that neither he nor the First Lady came from wealth, but said that anything was possible and that “the future holds anything.”

About 4:00 PM the President and the First Lady entered the wačhípi circle to a song of encouragement by the Grand River Singers. The crowd cheered. The President greeted the people in Lakȟóta, “Haú mitákuyapi” (Greetings my relatives). He spoke for 11 minutes about the improving relationship that exists between the federal government and American Indian nations, and giving Indian Country (referring to all the first nations of the United States) the resources to meet the needs of the youth.

The President told the crowd that he supports “returning control of Indian education to tribal nations with additional resources and support so that you can direct your children's education and reform [the] schools here in Indian Country.”

Chairman Archambault honored the President with a star quilt and Mrs. Archambault gave the First Lady a shawl. Dancers, including men, women, and children, danced for the President, exhibiting their living culture. “The pow-wow was a surreal experience. As we sat there, I explained to him the different dances,” said Archambault. When Chairman Archambault voiced his doubt that the President would actually visit Standing Rock, the President replied, “I wouldn’t miss it for the world!”

As a result of his visit, the President invited a group of Lakota young people to visit him in Washington D.C. and play basketball on the White House court. He immediately challenged members of the Presidential Cabinet to do all they can in their power and authority for Indian Country. He also established a native youth initiative with a focus on education.

When the Standing Rock young people traveled to the White House, they saw all the gifts from Standing Rock to the President and First Lady on display. “The Youth realized that the President’s visit meant more to him than just an afternoon on the reservation. He genuinely cared about the youth. And the youth were inspired to become productive members of their communities,” said Chairman Archambault.

...

Dakota Goodhouse is an enrolled member of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe. His research has appeared in the Smithsonian's The Year the Stars Fell, and other publications.

The ARC Lawsuit of 1982

By Dr. Kimberly K. Porter

In 1980, the Association for Retarded Citizens (ARC) of North Dakota filed a lawsuit against the state in order to improve living conditions at the Grafton State Home and its sister institution San Haven. Both institutions served as residential homes for the mentally handicapped. Twenty-three-year-old attorney Mike Williams represented ARC.

of the problems identified by the Association for Retarded Citizens. SHSND 30804-001-08

They received only minimal care from attendants. SHSND 30804-002-02

|

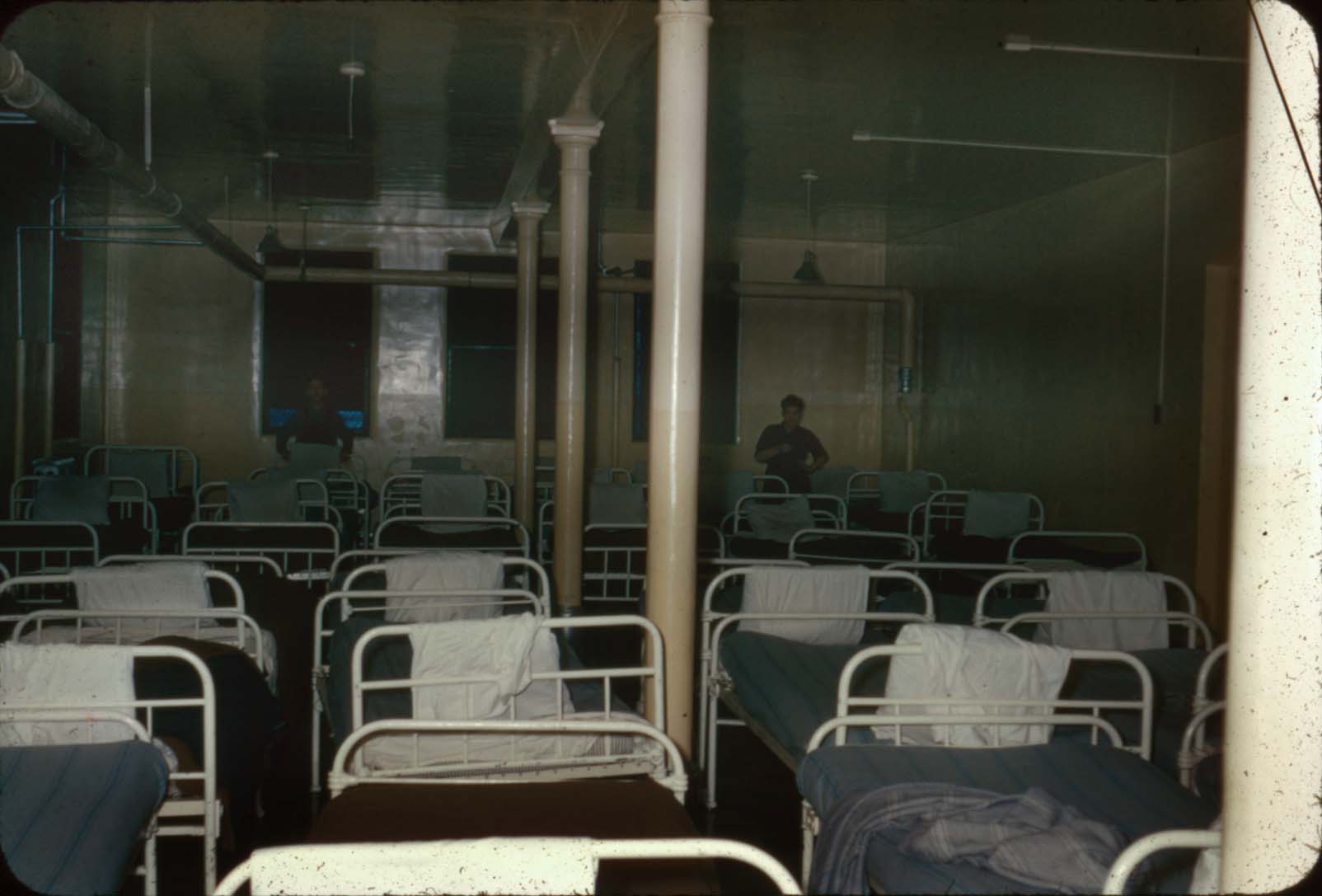

In his video-taped exploration of the facilities, Williams gathered evidence to support hundreds of federal violations. The buildings smelled of body fluids, patients wore dirty diapers for hours, and bored residents frequently pounded their heads or hands against wall in search of stimulation. Many patients wore no clothing; staff found dressing and changing individuals who were not toilet-trained was too time consuming. Some residents existed in mesh cages which kept them essentially bound to their beds.

Overcrowding and untrained staff as well as out-dated attitudes towards the developmentally disabled, combined to make the Grafton State School and the San Haven Institute chambers of horrors. In 1977, an unattended woman was scalded to death by hot bath water; residents suffered broken bones, bruises and neglect at the hands of those hired to assist them. When patients soiled themselves, attendants used stiff brushes to scrub them clean. Patients committed suicide. To control the residents in crowded wards, patients often received tranquilizers they did not need. Others were strapped to boards bolted to walls. Restraint devices kept patients strapped to their beds, toilet bowls, and in otherwise empty rooms.

ARC v. ND commenced in U.S. District Court on January 28, 1982, before Judge Bruce Van Sickle. In the lawsuit, ARC requested that the facility hire more attendants, that attendants be appropriately trained, that medicines be given for illnesses and chronic conditions, and that residents be provided proper dental, medical, and vision care. Moreover, the suit asked that the institutions regularly schedule activities for residents, that residents be allowed to practice the religion of their choice, and that they have appropriate clothing. The ARC also asked that residents be allowed to vote. The ARC asked for other changes including air conditioning, privacy, and fire safety for the residents. The facilities, according to the ARC, denied residents basic civil rights.

The state admitted that problems existed at Grafton and San Haven. The state defended the institutions by saying that it could not provide better care without more funding. When Judge Van Sickle heard this admission of responsibility, he ruled in favor of the ARC. His ruling declared that substandard conditions be improved. Besides ordering the state to comply with ARC’s requests, the judge ordered San Haven closed. Judge Van Sickle required that the number of residents at Grafton significantly reduced. He urged the movement of individuals to community homes scattered across the state. The state appealed, but failed to make a strong case. San Haven closed and most of the residents at Grafton moved into community homes. Conditions at the Grafton State Home improved and the welfare of the residents was assured. Today, the facility is home to less than 10% of the state’s developmentally disabled population.

...

Kim Porter is Professor of History at the University of North Dakota.

Trouble in Medina

By Dr. Kimberly K. Porter

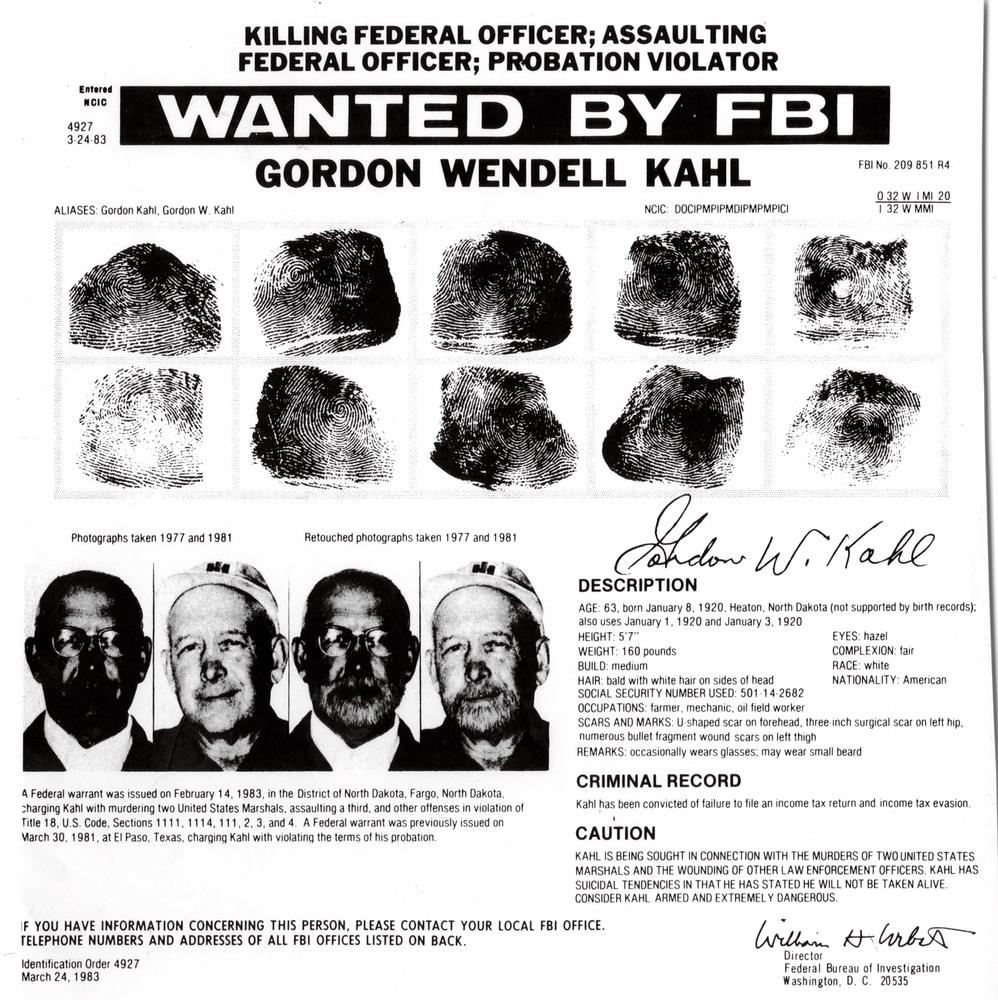

Gordon Kahl (1920–1983) once farmed near Heaton, North Dakota with his wife and children. In the winter, he often went to Texas to work in the oil fields. His oil field paycheck supplemented his farm income, but he wanted to be paid in cash so that he could avoid paying federal income taxes. By the 1960s, Kahl had come to believe that the United States government was oppressive. He continued to avoid paying income taxes. In 1967, Kahl notified the Internal Revenue Service, the agency that collects federal income taxes, that he would no longer pay taxes. He referred to the U.S. government as the “Synagogue of Satan under the 2nd plank of the Communist Manifesto.” Kahl’s views on taxes and the federal government were closely related to his religion and his interpretation of the Bible. Because he refused to pay taxes, Kahl was convicted of income tax evasion and spent eight months in prison. The federal government also confiscated some of his land to cover payment of his taxes.

Kahl was not the only person in the United States to hold radical views of the government. There were many individuals who believed that the people of the United States should still be governed by the Articles of Confederation (1781-1789) and that only Christian, white men should hold power. These individuals formed organizations such as the Posse Comitatus. Many also joined a movement of people who believed that government should never be larger than a township government. Suffering from poor crop prices and hard times in the 1980s, some rural Americans found comfort in these ideas and joined these radical political groups. Gordon Kahl was well-known for sharing some of these views. He also believed that a Jewish conspiracy plotted to take over the United States government.

On Sunday, February 13, 1983, the problems between Kahl and the federal government broke out in violence. During the afternoon, Kahl had attended a meeting in Medina, North Dakota. People at this meeting were interested in Posse Comitatus and the township movement. After the meeting, U. S. Marshals were waiting to arrest him because he refused to pay taxes. Kahl had also crossed state lines to find work which was in violation of his parole.

Kahl, his son Yorie, and follower Scott Faul attempted to avoid the arrest. Kahl and the others were armed. The marshals, also armed, had established a road block just north of Medina to stop Kahl. At the roadblock, both sides opened fire. Marshals Kenneth Muir and Bob Cheshire were killed. Deputy Marshal James Hopson, Yorie Kahl, Medina police officer Steve Schnable and Stutsman County Deputy Sheriff Bradley Kapp were wounded. Deputy U.S. Marshal Carl Wigglesworth survived. Kahl escaped in a police car.

Kahl left North Dakota seeking refuge. He remained at large until June, 1983 when he was found hiding in a private home in Arkansas. The owner of the home held views similar to Kahl’s. Federal agents surrounded the house and County Sheriff Gene Matthews entered the building. Kahl and Matthews apparently shot each other. Both died of gunshot wounds. Outside, marshals continued to fire at the house and set it on fire.

Kahl’s death ended the nation-wide manhunt. Yorie Kahl and Scott Faul were convicted of their part in the shooting at Medina and remain in federal prison. Many North Dakotans still remember the violence that took place at Medina.

Some people think of Kahl as a martyr to his beliefs. Others believe that he was a criminal. However, the death of one man does not kill his beliefs. The ideas that seemed true and important to Gordon Kahl are still found among people who seek truth in the wrong places.

...

Kim Porter is Professor of History at the University of North Dakota.

Recent Immigration

By Sarah Walker

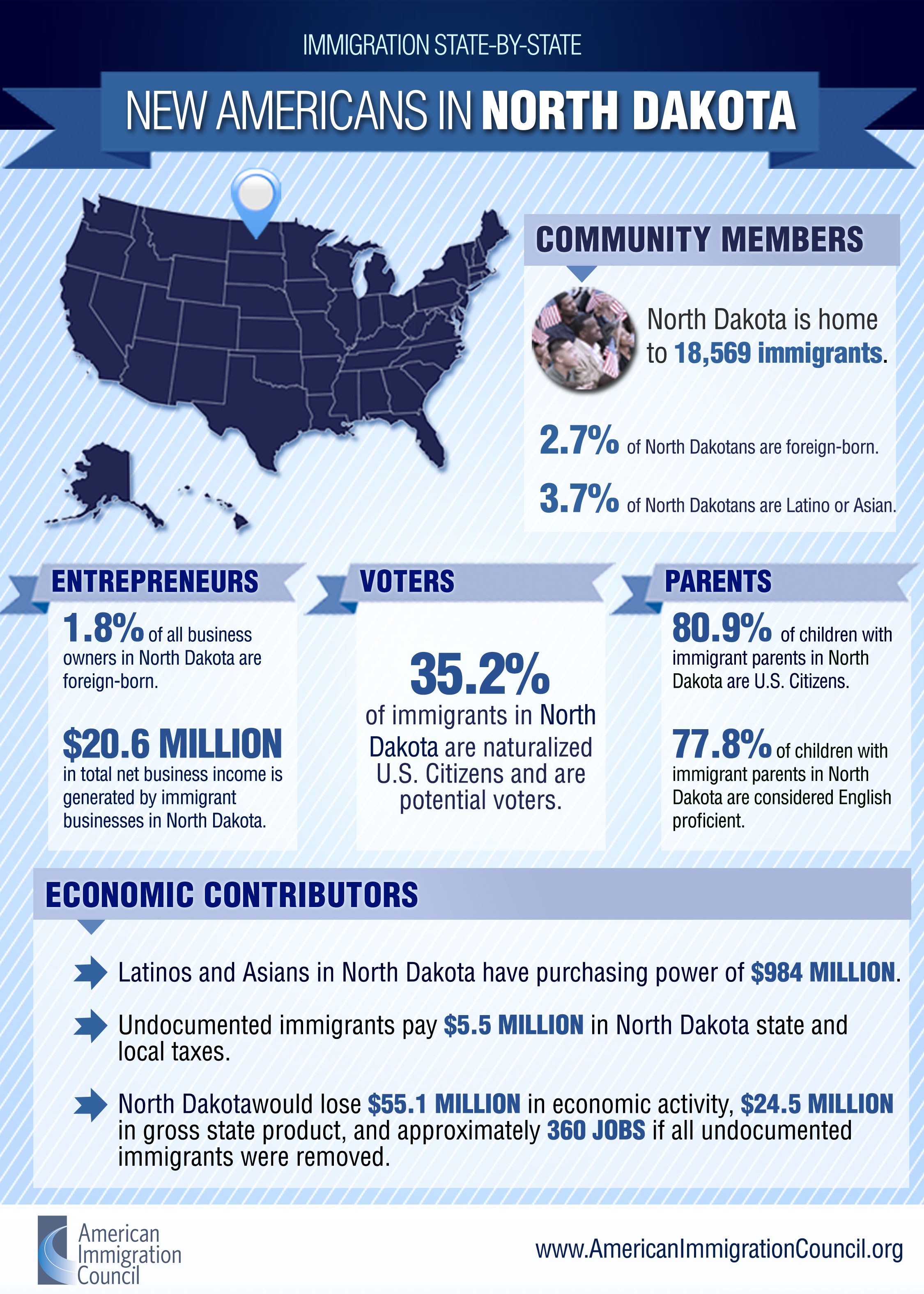

Immigration has long been a relevant topic in North Dakota’s history. Throughout the settlement and development of the land, immigrants have had a profound impact on the customs and culture around them. The reasons these men, women, and children come to North Dakota have remained largely the same, though the details change: they come for the promise of opportunity and to start anew, a theme that links the stories of more recent and earlier immigrants alike.

of the horror of civil war and his forgiving of those who killed his mother. Courtesy J. Musabyimana

Conflicts occurring in some countries have forced many refugees to leave their homes. Often, these individuals faced death every day. They fled their homes, sometimes without any possessions, sometimes without even a simple understanding of the English language. Some have resettled in North Dakota.

The immigrants of the 19th century came primarily from northern Europe. A few came from the Middle East. Recent immigration has broadened North Dakota’s ethnic diversity, increasing the ethnic diversity of our state.

In 1975, a refugee sponsorship program resettled 204 refugees from Vietnam in North Dakota. In the 1980s, Civil War broke out in Somalia. The war continues after two decades, and many Somalis sought refuge. With the help of the United States government and some church organizations, many Somali refugees arrived in North Dakota.

In the early 1990s, the United States welcomed Bosnian refugees as war in Bosnia led to ethnic cleansing in the former Yugoslavia. The United States and private refugee support organizations such as Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Service also welcomed refugees from the civil war in South Sudan. All of these refugees hoped to find work, education, safety and a better life in the United States.

North Dakota’s branch of Lutheran Social Services is one of the private organizations that have brought refugees to North Dakota. This group works with refugees for up to five years. Refugees are first offered orientation classes and help in learning English. Refugees receive aid in finding employment, housing, and education. Lutheran Social Services (LSS) has headquarters in Fargo and offices in other cities around the state. Since 1997, LSS has settled an average of 400 refugees per year in North Dakota.

So many Somali refugees settled here that a nonprofit specifically supporting this community was formed in Grand Forks. Within the first year of its recent formation, the Somali Community of Grand Forks helped about 1200 refugees with employment, language translation services, and cultural integration.

Not all of North Dakota’s new immigrants are fleeing war or disorder. Many came for a good education at one of the state’s universities and stayed to take advantage of job opportunities. About 43.5 percent of the science and math graduates at North Dakota’s colleges and universities are foreign-born. Among students receiving a doctoral degree in engineering, 76.2% were born outside of the United States. In addition, many of North Dakota’s medical doctors are immigrants to the United States.

Immigrants who struggle to learn English or who have not had a good education may find work in manufacturing or in retail positions where English is not important. Many find positions in health care. Some immigrants have opened food shops or cafés featuring the food traditions of their home countries. Between 2006 and 2010, 381 immigrants opened their own businesses in North Dakota.

A recent North Dakota immigrant is Jean de Dieu Musabyimana who came to the United States from his former home in Rwanda. As a child, he saw his mother and grandfather killed in the ethnic war between the Hutus and the Tutsis. Jean’s family was Tutsi but they were sheltered by sympathetic Hutus. Years later, Jean was able to forgive the family of those who murdered his mother. In 2014, Jean asked for and was granted asylum in the United States. Today, he lives in Dickinson and works at Walmart. He also speaks publicly about his boyhood in Rwanda. He has moved to Bismarck and is preparing to enter the medical field.

New immigration to North Dakota continues to occur. According to reports from the U.S. Census Bureau, between 2010 and 2014, 2.9 percent of the population living in North Dakota listed that they were foreign-born persons, and 5.4 percent listed that they spoke other languages than English at home. The addition of these immigrants from varied parts of the world only adds to the diversity and beauty of the fabric composing North Dakota. As long as there is opportunity for development and growth, this percentage should only increase into the future.

Recent immigrants to North Dakota have ample opportunity to establish homes, attend school, work. The settlement of new immigrants in North Dakota is also good for the economy and culture of the state, providing workers and broadening cultural horizons and awareness.

...

Sarah Walker graduated from the University of North Dakota in 2007. She has worked for the State Archives at the State Historical Society of North Dakota since 2008 where she is a Reference Specialist.

The Problem of Outmigration

By Jim Davis

North Dakota has wide open spaces, a low crime rate, and great educational and recreational opportunities. While it is true that winters can be harsh, it is a great place to live. What causes the so many of our young adults to leave the state? For some it is the desire of adventure, others may be seeking a spot in the corporate world, but for most, living in or leaving North Dakota is a matter of “commodity economics.”

required extra workers at harvest time. Wheat and other agricultural crops have remained the foundation of North Dakota’s economy. A good wheat harvest brought

temporary workers and new settlers to North Dakota SHSND 0075-00696

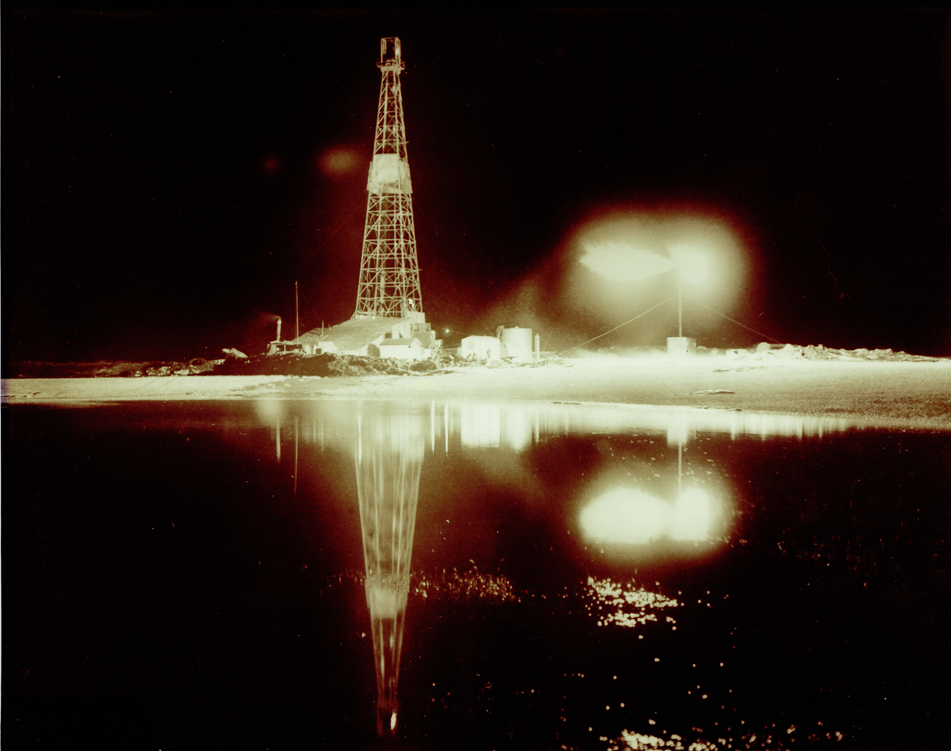

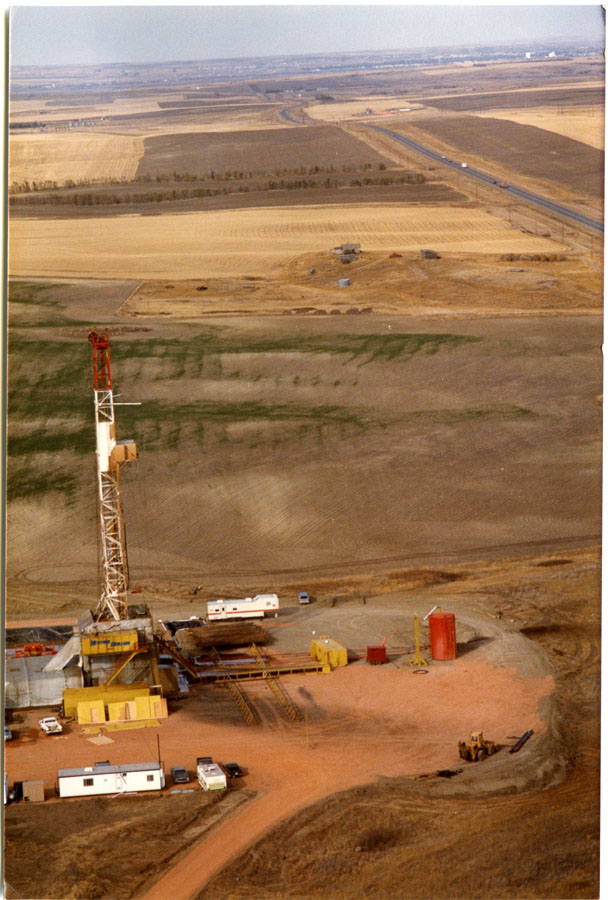

The lights of the rig shine brightly on new-fallen snow. Oil will soon bring new workers to the state. SHSND 10958-59-01

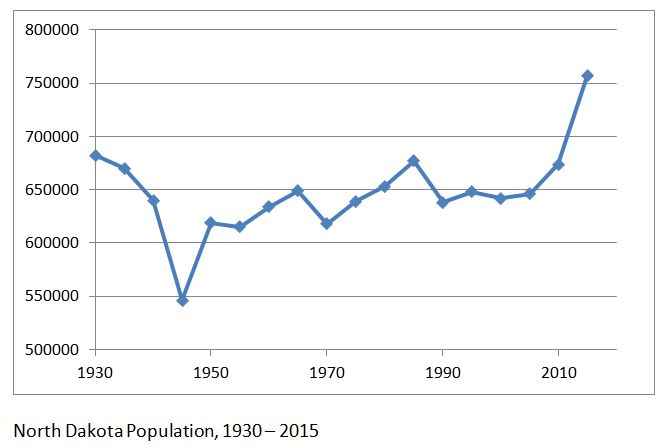

The population reached its lowest point in 1945. Though people returned to the state after World War II, the population did not reach its 1930 level until 2011.

Commodities are goods which are bought or sold on the open market. Throughout its history, the economy of North Dakota has been tied to commodities, especially wheat and oil. These commodities have not only defined the lifestyle of the people of the state, but have had a profound influence on its population. The rise and fall of grain prices on the commodities market can affect the long term stability of North Dakota’s economy and create a population outmigration. It is the boom and bust cycle in oil country that creates the most dramatic swings in our population.

When the tracks of the Northern Pacific Railroad crossed the Red River in 1872, thousands of immigrants sought the fertile prairies of Dakota Territory. Wheat was “King” and by 1930 the population of North Dakota climbed to a peak of 682,000. But drought and a prolonged poor national economy during the Great Depression of the 1930s wreaked havoc on the Plains. Crops dried up, livestock died by the thousands from lack of feed and, with no other source of income, many famers could not pay their taxes or mortgages and lost their land. Over 60,000 people left the state during the next two decades.

In April of 1951, oil was discovered near Tioga ushering in a new era and a new commodity for North Dakota’s economy. Oil field jobs brought on a huge influx of workers to operate the rigs. In the months immediately following the discovery of oil, workers were arriving at the rate of 200 to 300 per day. While most worked in the oil fields, some found work at the refinery in Mandan or at the Garrison Dam as it neared completion. The oil found in the deep strata of shale rock proved difficult and expensive to extract. When crude oil prices dropped on the commodities market, drilling nearly stopped altogether. Jobs were lost, businesses were abandoned, and the workers moved on.

There was a short period of time when construction work helped to raise North Dakota’s population. During the 1960s, North Dakota’s population was affected by Cold War tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union. New jobs were created when the Grand Forks and Minot Air bases were established. Workers were needed to build the bases and the Intercontinental Ballistic Missile bases and silos. Construction on Interstate highways and Highway 2 (also related to missile systems) also created new jobs. Outmigration paused during this construction boom. But even with this limited prosperity, by 1970, the population had shrunk to 617,000. But an agricultural boom was on the horizon.

In the early 1970s, the global wheat trade strengthened. Worldwide crop failures, coupled with the devaluation of the US dollar, sent prices for wheat soaring to new highs. The new-found prosperity created agricultural jobs which supported banks, railroads, small town merchants, and many other businesses. The outmigration of college graduates slowed down, and many people who had left the state returned home to their roots. Farmers were encouraged to plant as much as possible. Farmers borrowed heavily to purchase additional land and modernize equipment.

However, overproduction of wheat eventually caused a rapid decline in the price. By the early 1980s, many farmers had failed to repay loans and they were forced off their farms. These displaced farmers sought jobs in urban areas outside the state.

In 1973, the Arab oil embargo caused motorists to have trouble locating gasoline. Gas was rationed among the service stations. The embargo forced oil prices to rise which encouraged more oil extraction in the North Dakota oil fields. Another oil boom was underway. The result was a population increase of over 30,000 people. However, and the North Dakota Legislature put a heavy tax on oil production.

However, the decade of the 1980s proved to be as volatile as earlier decades. By 1982, OPEC (Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries) had flooded the market with oil. The price of oil dropped. Low prices together with North Dakota’s oil extraction tax encouraged oil producers to limit drilling. Oil workers were forced to go elsewhere in search of jobs. Once again, the oil patch was deserted. Business in oil towns slowed down. Buildings stood empty.

North Dakota saw little growth in the 1990s, however less outmigration occurred as more effort was put into introducing a wider variety of manufacturing jobs. Then, a new technique in oil production known as “fracking” allowed for a resurgence in oil production in the 2000s. Once again, the population of the “oil patch” swelled dramatically. Frantic activity was ongoing as oil prices topped $50 per barrel and went as high as $90. But in 2016, with the cascading fall in the price of oil, production dropped by 70% leaving thousands of oil rig workers and those in supporting businesses out of work. A new wave of outmigration began, showing that “commodity economics” still plays a significant role in living in North Dakota- or leaving. Both young and old leave the state when jobs are scarce, but it is the young people who are missed the most.

...

Jim Davis holds degrees from Lake Region Junior College and University of North Dakota. He has worked for the State Archives and Historical Research Library of the State Historical Society of North Dakota since 1980 where he is currently Head of Reference.

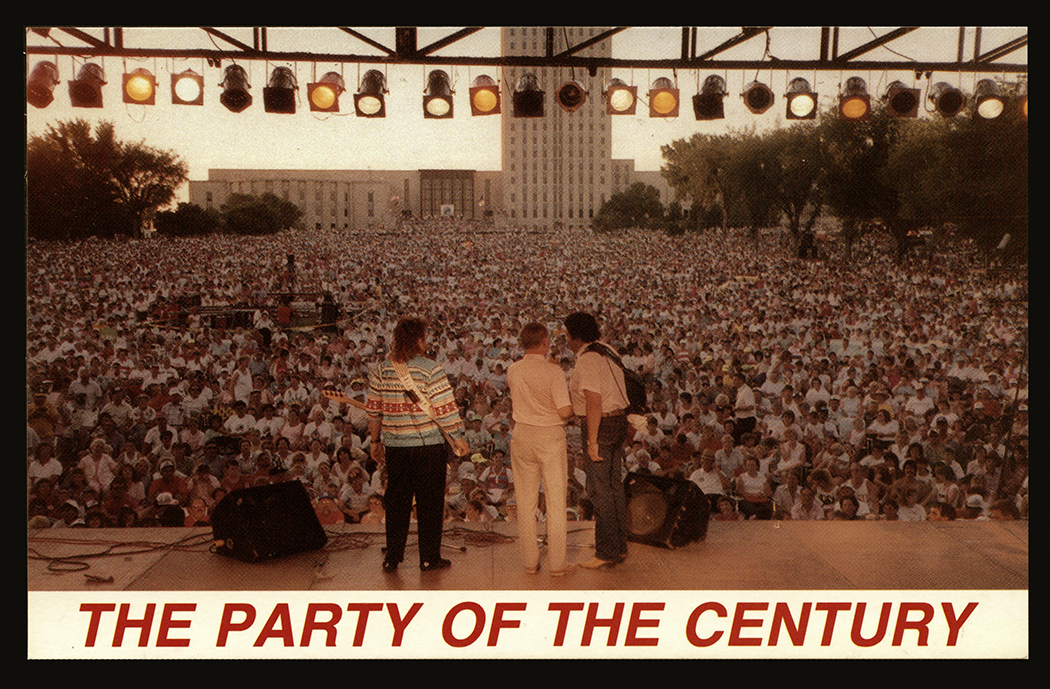

Centennial: Party on the Prairie

By Barbara Handy-Marchello

North Dakotans began to think about celebrating the state’s 100th anniversary in the 1970s. In 1981, the state legislature established and funded the North Dakota Centennial Commission led by former Governor Arthur Link.

who were members of the Centennial Commission. The official centennial flag flies on the car along with the state and U.S. flags. SHSND 10943-77

represents the American Indian peoples of North Dakota. SHSND 00853-0004

Centennial Decade of Trees project. SHSND 31843-box11-folder 4-0005

The commission made plans to celebrate the anniversary on several important dates in cities around the state. The biggest celebration was on July 4, 1989 in Bismarck. The celebration marked the 100th anniversary of the Constitutional Convention which wrote the state’s constitution. An estimated 100,000 people came to Bismarck for the Party on the Prairie.

Centennial events were funded largely by the sale of official commemorative items such as medallions, coins, and belt buckles. Other items were produced by vendors who made dolls, quilts, china cups, and other things. Any vendor who used the Centennial logo paid a royalty of seven percent to the state. The income from sales of commemorative items totaled $2,058,437 or 57% of the centennial budget.

Though the celebration officially ended on November 2, 1989, Statehood Day, the Commission arranged for the state to have a long-term, living legacy of the centennial. The North Dakota Centennial Decade Trees Project was initiated when President George H.W. Bush came to North Dakota to plant an American Elm tree on the state capital grounds. Over the next 10 years, the commission planned to see thousands of trees planted. The trees would “carry the centennial spirts well into the second century of statehood,” according to Governor Link.

Governor George Sinner said that “the state’s Centennial was really a celebration of the people, by the people, and for the people.” North Dakotans could take “pride in the quality of life here.”

...

Barbara Handy-Marchello is retired from the University of North Dakota History Department. She currently works for the North Dakota Studies program at the State Historical Society of North Dakota.

Abortion Rights

From 1910 to 1972, most abortions (the medical termination of a pregnancy) were illegal. Many states allowed abortion only to protect the life of the mother. During those years, women sometimes resorted to illegal or self-induced abortions when they felt it was necessary. Some women died from these procedures.

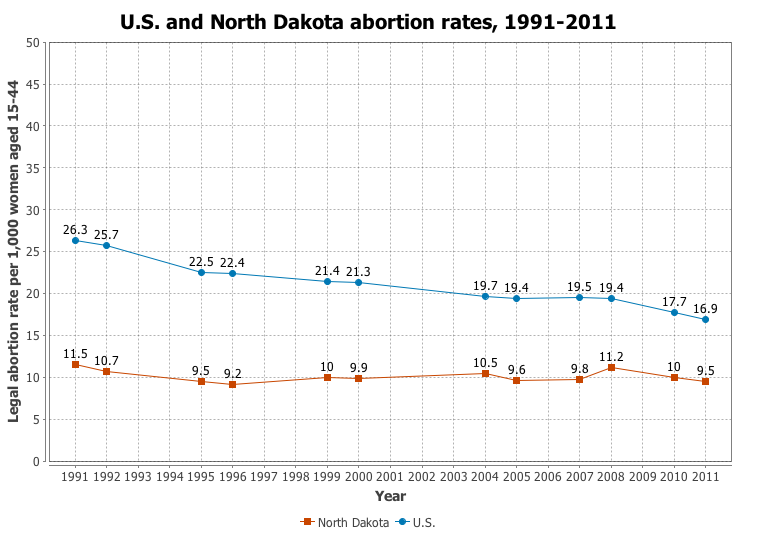

has been less than half the national rate. However, North Dakota’s abortion rate has been fairly steady

for the past 20 years. Courtesy, State Facts about Abortion, North Dakota, Fact Sheet, New York: Guttmacher Institute, 2015 Link

People with differing views raise their voices in support of the right to legal abortion. Courtesy, Red River Women’s Clinic

Many women and men believed that abortions should be legally available. It was necessary to challenge the laws prohibiting abortion through the court system. In 1972, a woman identified by the false name (to protect her identity) Jane Roe filed a lawsuit in the state of Texas. The lawsuit was heard at different levels of state and federal courts. In 1973, the case, known as Roe v. Wade, was heard by the Supreme Court of the United States. The Court decided (7 to 2) that a woman’s right to privacy as protected by the 14th amendment to the U. S. Constitution included the right to an abortion. As a result of this decision, 46 states changed their laws on abortion.

In 1972, a year before Roe v. Wade, an initiative on abortion rights was presented to North Dakota voters on the ballot. The initiative failed by a vote of more than three to one. Nevertheless, when Roe v Wade was decided by the Supreme Court, North Dakota had to allow abortions within certain limits. For the most part, these medical procedures were performed in doctor’s offices. In 1981, the Women’s Health Organization (WHO) opened a clinic in Fargo.

The clinic had a difficult time finding a place to rent and staff to hire, but when it opened, there were patients. There were also many North Dakotans who believed that abortion was immoral and should be made illegal again. The challenges to legalized abortion in North Dakota took two paths.

The most persistent challenges were directed towards the WHO clinic, which by 1990 was the only place to obtain a legal abortion in North Dakota. Protesters marched in front of the clinic and sometimes harassed the staff. In 1991, a group from other states came to Fargo with the intention of putting the WHO clinic out of business. Many of the protesters were arrested; the clinic remained open.

The other challenges came through the legislature. Between 1990 and 2015, more than 1000 bills were introduced to regulate, outlaw, restrict, or reduce access to abortions. Some of these bills were approved by legislators: of these some were vetoed by the governor, some were referred to the voters and did not pass. The bills that did become law did not ban abortions, but regulated them. Some laws that presented major obstacles to legal abortion were challenged by abortion providers.

In March 2013, the North Dakota legislature passed the most restrictive abortion law (House Bill 1456) in the United States. The law made abortions illegal if the doctor detected a fetal heartbeat. Fetal heartbeats can be detectable by ultrasound at six weeks.

The only abortion clinic in North Dakota (the Red River Valley Women’s Clinic) filed suit challenging the constitutionality of the law in July 2013. U. S. District Court Judge Daniel Hovland ruled the law unconstitutional. The state carried the lawsuit to the Supreme Court. On January 25, 2016, the justices of the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear the case. That means that the lower court’s ruling was allowed to stand. The law, H.B. 1456, would not go into effect.

Another legislative effort to eliminate legal abortion in North Dakota was referred to voters in 2014. The “Human Life Amendment” was defeated by voters at the November elections.

Today, the only abortion provider in North Dakota is the Red River Valley Women’s Clinic in Fargo. In addition to abortions, the clinic provides other services such as pregnancy testing and birth control counseling. The clinic performs about 1,200 abortions each year. Organizations that oppose abortion as a solution to a problem pregnancy provide counseling to patients at several clinics around the state.

...

Completing Interstate Highways

By Dr. Kimberly K. Porter

Two Interstate Highways cross North Dakota. Interstate 29 parallels the Red River on the eastern side of the state and Interstate 94 runs east-west across the southern third of the state.

and Interstate 29 were completed in North Dakota, the population was still quite small. Driving on the interstate

highway was pleasurable for North Dakotans because the highways were well-made, there were few reasons to stop,

and traffic was very light. This view of I-94 was taken from a bridge in central North Dakota. SHSND 32256-C-01193

danger areas and to transport missiles to the missile fields in North Dakota, South Dakota, Wyoming, Montana, and Nebraska. SHSND 2009-P-25-09

good highways connecting the state’s major cities to recreation areas such as the badlands. SHSND 32256-C-1212

The nation’s interstate system was a plan that came from President Dwight Eisenhower’s office. Congress passed the National Defense Highway System Act of 1956. This law funded the construction of the interstate highways.

The highways were designed and built in the time of the Cold War when the United States was concerned about nuclear war with the Soviet Union. The interstate highways were designed to move large numbers of people out of cities in case of war. The highways were also designed with limited access and wide lanes to move military weapons.

In the fall of 1960, Interstate 29 was completed to the Canadian border, becoming the first highway to connect with a foreign country. In 1961, Interstate 94 was opened to traffic from Dawson to the Red River. North Dakota’s interstate system was completed in 1977 providing excellent highways for North Dakota residents and tourists.

...

Kim Porter is Professor of History at the University of North Dakota.

Opinion

Where We Are Now

North Dakota built its towns, schools, and other institutions on a land-based, farming economy. Most of the people who lived here were hard workers with European heritage. Rich in fertile soil, but short on population and industry, North Dakota has had a pretty steady, reliable, if not exciting economic and social history. This picture of North Dakota prevails through the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s.

Early oil production made a small blip North Dakota’s radar screen. Here – then gone. Towns in oil-rich counties and reservations leaped at the promise of growth, but were disappointed by the shuttering of oil operations in the early 1980s. These towns returned to the quiet existence of small farm communities.

But change had begun, and though progress was slow, it would not go away. Our population gained new cultural features with the airmen assigned to Grand Forks and Minot Air Force bases, students and staff at the state’s universities, and refugees seeking a peaceful life in the United States. The coal industry grew with exciting new technologies. Nevertheless, we protected the land even as we developed coal industry, so former coal mines could be returned to agricultural purposes. Our confidence in the land was strong; the land would always sustain us.

But suddenly, around 2008, everything changed. Oil came back BIG, and it coincided with a severe economic depression in the rest of the nation. Sleepy North Dakota towns became the destination of Americans from everywhere and all walks of life. Oil production revenues filled the state treasury with billions of dollars.

Of course, agriculture had always had its ups and downs. Drought, insects, excessive rainfall and flooding periodically harmed crop production. Some years, blizzards killed thousands of cattle or drought forced ranchers to sell their livestock. Poor market prices for crops or livestock were a recurring challenge for farmers. On the other hand, farmers diversified their crops and modernized their operations in order to manage and stabilize their income. In good years and bad years, farm families lived within their means and remained on their farms.

Having always been good at saving money (because we never knew when that rainy day would come), our state bank accounts were usually “in the black.” After 2009, however, oil revenue brought a huge surplus. We seemed to have more money than we could spend.

North Dakotans were excited and awed by this success and wealth. We cautiously welcomed newcomers with different accents, habits, and skin color. We re-built our roads for oil traffic and enlarged schools and hospitals. We enjoyed prosperity while the rest of the nation struggled.

Just as quickly, a few years later, oil production closed up again. And now, we understand that, like the rest of the nation, we will struggle with periodic economic upsets on a much larger scale than we had experienced with an economy based on agriculture. We adapted well to exuberant prosperity and a new vitality of our people. Now, our task is to adapt to the rock and roll of an economy that grows and shrinks in world markets. A tough job, but our experience suggests it is not beyond our ability. Just like our ancestors, we have the ability to adjust to both prosperity and loss.

Political News

• North Dakota Indian Affairs Commission

• Tribal-State Relationship

• Lowering the Voting Age

North Dakota Indian Affairs Commission

By Dakota Goodhouse

In 1949, the North Dakota Legislature created the North Dakota Indian Affairs Commission (NDIAC). The first responsibilities of the NDIAC were to help American Indians find work in agriculture or other businesses, to coordinate federal and state programs for American Indian tribes and individuals, and to evaluate the need for state and federal aid programs.

In the early years of the NDIAC, the commission encouraged American Indians to assimilate or adopt Anglo-American cultural ways. Commissioners believed that assimilated Indians would work and live in the general population and engage in business and social relations with non-Indians. In addition, the commission was interested in “termination policy” which favored closing reservations and making the land available to the states.

In 1952, Congress decided to abolish the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa reservation. The NDIAC, which was composed entirely of non-Indians, supported termination even though executive director John B. Hart expressed doubts about the policy. Even though Congress terminated the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa, the tribe challenged and successfully reversed that decision to retain their recognition and rights.

Over the next few years, NDIAC turned away from termination and assimilation to investigate many important issues, including an effort by the federal government to determine a new and more specific definition of who an “Indian” is. The commission also considered how off-reservation American Indians access the benefits of all North Dakota citizens, such as medical care, education, housing, and employment.

The NDIAC changed with the needs and growing power of the tribal nations. In 1959, the tribes of North Dakota were given a voice on the NDIAC board. The chairmen of the Three Affiliated Tribes, the Standing Rock Sioux, the Devils Lake (now Spirit Lake) Sioux, and the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa were appointed to the commission. In 1963, Governor William Guy appointed Hans Walker, Jr. of Three Affiliated Tribes to executive director of the commission. He was the first American Indian to hold the position. The presence of American Indian leaders on the commission was a long-sought step toward self-determination of Indian tribes.

The NDIAC continued to improve the relationship between the state of North Dakota and the four Indian nations within the state. In 1999, the 50th anniversary of the commission, the NDIAC updated its goals to include “work for greater understanding and improved relationships between Indians and non-Indians” and “to assist tribal groups in developing increasingly effective institutions of self-government.” To promote those goals, the NDIAC co-sponsored the University of North Dakota’s Writers Conference, which featured Native American authors and film makers, and brought their work in contact with the general public.

Today, the commission’s work includes promoting educational awareness and opportunities, economic advantages, improved health care, the pursuit of cultural traditions. The commission also supports a legislative effort to adopt a requirement for educators to have at least one college course in American Indian Studies to teach in North Dakota.

...

Dakota Goodhouse is an enrolled member of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe. His research has appeared in the Smithsonian's The Year the Stars Fell, and other publications.

The Tribal-State Relationship

by Dr. Birgit Hans

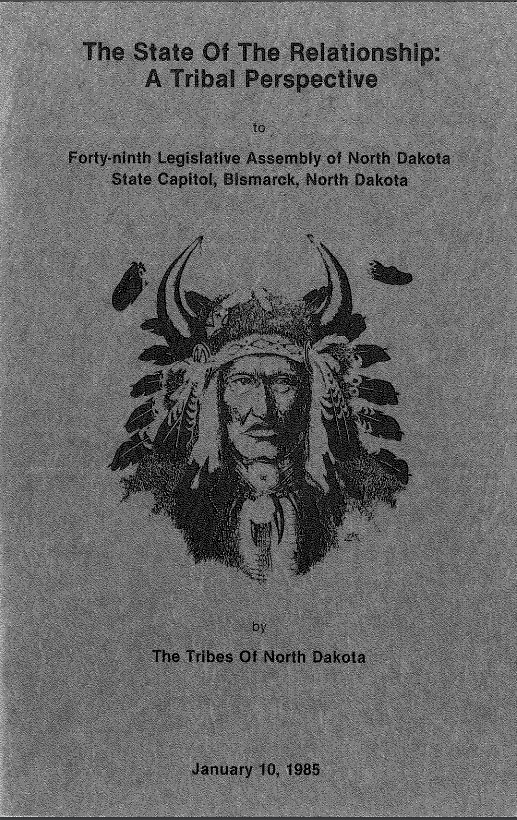

In 1985 the members of the North Dakota legislature listened to the first “State of the Tribal-State Relationship” address delivered by the Honorable Russell Hawkins, Chair of the Sisseton-Wahpeton Sioux Tribe. Hawkins described the problems faced by American Indians of North Dakota. Since then, one of the tribal chairpersons of the Five Tribal Nations in North Dakota has delivered such an address at every legislative session.

The first tribal chair to address the North Dakota Legislature on the state of tribal-state relationships was the Honorable Russell Hawkins, Chair of the Sisseton-Wahpeton Sioux Tribe. Courtesy, United Tribes Technical College

Every “State of the Tribal-State Relationship” address has placed high value on the sovereignty of tribes and their governmental relationship with the state government. Tribal sovereignty grew from treaties the tribes signed with the federal government. Sovereignty was affirmed by the United States Supreme Court in two landmark cases. In both Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831) and Worcester v. Georgia(1832), the Supreme Court recognized tribes as sovereign because the U.S. government had negotiated treaties with them. In other words, the tribes had the power of a nation to govern themselves and to deal with other nations on an equal basis. According to these two court decisions, American Indian nations have the same rights as states. However, during the course of the 19th century, tribes lost much of their sovereign power to the U.S. government. In the 20th century, the tribes began to reclaim their right to sovereignty.

By emphasizing sovereignty in the biennial speeches to the North Dakota legislature, tribal representatives strengthen the idea that American Indian nations and the state of North Dakota are equal under the U.S. Constitution. Tribal governments make decisions that affect tribal members on the reservations.

In the 2015 address the Honorable Dave Archambault, chairman of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, said: “We ask that North Dakota reconsider its approach to its government-to-government relationships with the five Tribal Nations, and bear in mind that although tribes embrace elements of a shared history, each tribe is also unique.” He indicated that the recognition of tribal sovereignty is still and issue for the state. It is important, he noted, that agreements between tribal governments and the state take into account geographic, economic and historic differences among tribes.

Although non-Indians in North Dakota find it difficult to recognize tribes as unique and complex cultures, there have been some successful cooperative endeavors in the last ten years. Take, for example, the compacts regarding gaming on reservations. The State of North Dakota has a separate compact with each tribe concerning regulation of gaming at tribal casinos. These compacts have benefitted the rural population of the state by creating employment opportunities for Indians and non-Indians alike. The recurring statements about the sovereignty of tribes do not exclude arrangements that are mutually beneficial to both the tribes and the state of North Dakota.

Unfortunately, the social and economic issues that make these government-to-government negotiations between tribal and state governments so important have remained essentially the same through the decades. These issues include education, unemployment, substance abuse, lack of health care, housing needs, infrastructure, and water management. In recent speeches, the tribal chairmen have outlined problems caused by oil and gas development.

The “State of Tribal-State Relationship” speeches emphasize that what affects American Indians on reservations also affects the rural population of North Dakota. It is therefore in the best interest of both the state and the tribes to work as partners. As the Honorable Charles W. Murphy, former chairman of the Standing Rock Sioux, said in his speech in 2005: “Our Tribal-State relationship will flourish through cooperation, respect, and communication. We’ve been working on that for the past 20 years and we must continue doing so in the future.”

...

Birgit Hans is Professor of Indian Studies at the University of North Dakota.

Lowering the Voting Age

By Lloyd Omdahl

While interest in lowering the voting age to 18 had been expressed in earlier years, it took the wrenching experiences with the Vietnam War and violent draft protests in the late 1960s to force the nation to respond to the argument that “Old Enough to Fight” also meant “Old Enough to Vote.”

his chosen candidate in 1972. McGovern lost to Richard Nixon.

SHSND 1986.00241.00119

By the time the issue rose in Congress, support for 18-year-old voting had solidified and both the Senate and the House exceeded the two-thirds vote requirement and submitted the proposal for the Twenty-sixth Amendment to state legislatures. However, before the states could act, a lawsuit was filed and the scrutiny of the Supreme Court was invoked.

Ever since the adoption of the Fifteenth Amendment guaranteeing the right to vote to former slaves in 1870, legal consensus held that constitutional amendments were required to alter voting rights. This interpretation was confirmed in 1920 by the adoption of the Nineteenth Amendment guaranteeing women the right to vote.

In March of 1970, however, advocates of lowering the voting age had concluded that the amending process was too slow. The war was hurting young people in the present and it would take years to complete the tedious amending process. So Congress passed an ordinary statute lowering the voting age.

This law was immediately challenged. In Oregon v. Mitchell, the Supreme Court ruled in December 1970 that Congress had the authority to set the voting age for federal elections, but the states made the rules when it came to state and local elections.

The decision created an untenable situation for states administering elections. The decision meant that states would be required to conduct two separate elections – one for president and members of Congress and a separate one for governor, legislatures and local officials. Because states did not wish to implement an election process wrought with confusion or added expenses, they were eager to ratify the Twenty-sixth Amendment to restore a single election process.

While previous amendments had required years to adopt, the required number of 38 states adopted the Twenty-Sixth in 1971. It took only three months, the speediest adoption of all amendments.

While support for an amendment lowering the voting age at the federal level had been building for years, the states were not idle. Georgia lowered the voting age to 18 in 1943 followed by Kentucky in 1955. Alaska and Hawaii entered the Union in 1959 with 18-year-old voting.

North Dakota was not idle. Three years before the national initiative, the 1967 legislative session proposed a constitutional amendment lowering the voting age to 19 and submitted it to the electorate for a vote in the September 1968 primary.

A core of young people across the state led the campaign. One of the leading activists on behalf of the proposal was Kent Conrad (later U.S. Senator) who reported that 50 to 60 activists, mainly from the Bismarck area, raised $15,000 to $20,000 and distributed supporting literature at every gathering of crowds across the state. However, when the votes were counted, the measure lost 61,813 (51%) to 59,034 (49%). Conrad attributed the margin of loss to a sensational auto wreck immediately preceding the election in which three young people were killed due to youthful indiscretion.

The issue of lowering the voting age was not without political implications. Both Republicans and Democrats speculated about the political beneficiaries of a lowered voting age. Even though Republican Presidents Dwight Eisenhower and Richard Nixon endorsed the idea, it was Democrat Ted Kennedy who introduced it in Congress.

Local politicians also were concerned about college students taking over city governments and legislative races when their connections to local communities were tenuous at best. This concern led to long-running battles over the definition of “residence” for voting purposes.

Even though young voters have not delivered on the claim that their involvement would result in higher turnover of elected officials, some jurisdictions are now looking at lowering the voting age to 16. In 2013, Takoma Park, Maryland, was the first local government to adopt the proposal.

Though North Dakotans appeared to support a lower voting age, the state never ratified the Twenty-sixth Amendment. The ratification process started in March 1971, in the middle of a biennial North Dakota legislative session. By the time the 1973 session rolled around, 43 states had already fulfilled the three-fourths requirement for ratification. Consequently, North Dakota remains as one of seven states that didn’t bother to ratify the Twenty-sixth Amendment.

...

Lloyd Omdahl is a former Lieutenant Governor of North Dakota (1987-1992) and a retired professor of Political Science at the University of North Dakota.

Environment & Energy

• The Bakken Oil Field

• Coal Creek Station

• Coal Mine Reclamation

• Diverting and Feeding the Red River

• Water Lifelines

The Bakken Oil Field

By Clarence Herz

North Dakota first produced petroleum in what was then referred to as the Nesson Anticline in the Williston Basin in April of 1951. However, petroleum production later fell dramatically from a 1967 peak of over 25 million barrels of oil to a little more than 20 million barrels in 1972. In 1973 political forces and war in the Middle East changed American policy toward petroleum.

to a fast-paced industrial area. SHSND 10958-26-118-6

North Dakota between 2009 and 2015. Courtesy Mr. Granger Creative Commons

In 1973 the Arab-Israeli War broke out between Israel and the Arab nations of Egypt and Syria. The United States, under President Richard Nixon, backed and re-supplied the Israelis while Russia supported the Arab nations. As a result of the United States’ involvement the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), led by its Arab members, instituted an oil embargo against the United States, the Netherlands, Portugal, and South Africa.

The OPEC embargo shocked global petroleum markets and the price of oil quickly rose from $2.90 ($13.90 today) a barrel before the crisis to $11.65 ($55.90 today) by January 1974. In response the United States instituted policies of conservation. The highway speed limit was lowered to 55 mph and U. S. oil producers were encouraged to increase petroleum production. This led to an increase in activity in the Williston Basin as the price of oil again made it profitable to produce oil in North Dakota.

Petroleum production, now driven by higher prices, led to the second North Dakota oil boom from 1974 to 1984 in the Williston Basin. This boom was driven by petroleum markets which were largely controlled by OPEC. In 1973, North Dakota drillers completed 134 new wells, but in 1974, that number jumped to 240 and climbed to 260 in 1977.

While the market for petroleum remained high, the boom continued and production once again began to climb. In 1984, 3,698 wells produced nearly 51 million barrels of oil annually. However, the nationwide market for petroleum fell once again in the mid-1980s and the boom ended. In North Dakota, the boom ended abruptly. Thousands of oil workers and their families left the area practically overnight. The number of producing wells declined. Williston, Watford City, Dickinson, and Belfield, once home to workers from throughout the United States, were now blighted by abandoned mobile homes, empty houses, and incomplete construction projects. The cities had heavy debt burdens related to their previously booming growth.

The 1986 oil bust affected western North Dakota for decades. Throughout the late 1980s and the 1990s production of petroleum in North Dakota rose and fell only slightly. During this time, petroleum companies continued to search for better and cheaper ways to produce oil in the Williston Basin, but little would change without a technological breakthrough.

Technology in the Williston Basin had not changed in fifty years. Companies drilled vertical wells into the producing formation, perforated the well by setting off explosives to break open the rock. Oil workers then added some acid or hot oil and waited to see what kind of production they would get. That all changed when companies began drilling horizontal wells in the late 1980s. Meridian Oil was the first to drill horizontal wells into the Bakken formation beginning with their 1987 well the MOI Elkhorn 33-11H.

Having succeeded at drilling horizontal wells companies still faced geologic problems unique to the Williston Basin. The most complicated problem was what geologists refer to as tight oil. Tight oil is the term used to describe petroleum that consists of light crude oil contained in petroleum-bearing formations of low permeability, such as sandstone. Permeability is a geologist’s term that refers to how easily oil can flow through the pore spaces in rock or sediment. The rock in North Dakota’s Williston Basin does not easily permit the flow of fluids. Vertical and horizontal wells in the “low perm” wells found in the Williston Basin produced little petroleum in relation to the cost associated with drilling the well.

Continental Resources drilled its first horizontal well in 1995, but was not satisfied with the results. The company continued to explore ways to extract oil from the rock. In March 2004 Continental finally drilled a commercially successful well. This well, the Robert Heuer 1-17R, was drilled horizontally and fractured. When working a fracture-stimulated well, workers pump sand, water, and chemicals down the drill hole under extremely high pressure to force the sand into the pores of the rock. The fracturing materials force the light crude oil out of the rock in quantities that are economically advantageous to the oil company.

Continental’s Robert Heuer 1-17R well kicked off a new oil boom based on fracturing technology. The boom lasted from 2004 until 2008 when a global financial crisis caused petroleum prices to fall. Many producers sold their holdings and left the area.

The region, referred to as the Williston Basin for nearly fifty years, now came to be known as the Bakken. It was named for the geological layer or stratum where producers were finding oil about 10,000 feet below the surface. The Bakken formation was named for Henry O. Bakken, a North Dakota homesteader who once owned the land where the second producing oil well was drilled. Bumper stickers and t-shirts began appearing throughout the oil patch proclaiming North Dakotans were “Rockin’ the Bakken.”

In 2009, as oil prices were recovering, Brigham Petroleum drilled a well that far exceeded all previous production records kicking off the “boom to end all booms.” North Dakota’s petroleum industry was in the news daily as thousands of companies, job seekers, thrill seekers, roughnecks, roustabouts, and criminals flocked to the region looking to capitalize on North Dakota’s good fortune.

Man camps (housing units for workers) sprang up across the western prairies as companies struggled to find housing for their employees. Cities and towns in the Bakken struggled to provide space and services for a growing number of students, criminals, and sick people. Between 2009 and 2014 the Bakken was big news across the state, region, country, and world as petroleum production continued to climb, finally exceeding 1 million barrels per day in the spring of 2014.

The old adage what goes up must come down held true for the Bakken as prices slowly declined. from 2014 to 2016 producers continued their exodus from the state leaving doubt as to what the Bakken would look like in the future. By January 2016, oil prices had fallen below $30.00 per barrel for the first time in decades causing all but the most dedicated producers to pack up and leave the Bakken.

...

Clarence Herz, originally from Linton, is a graduate of North Dakota State University. He is currently working on a Ph.D. dissertation about the North Dakota petroleum industry from 1917 to the present.

Coal Creek Station

by Cathy A. Langemo

Located 50 miles north of Bismarck is North Dakota’s largest power plant, Coal Creek Station. Owned by Great River Energy (GRE) which is headquartered in Minnesota, the plant’s two units can generate 1,210 megawatts each. Unit 1 started generating electricity in 1979 and Unit 2 in 1980. With more than 200 employees, Coal Creek is one of the largest employers in McLean County.

Coal Creek plant burns about 22,000 tons of lignite per day or about eight million tons per year. The plant used coal mined nearby at the Falkirk Mine.

Great River Energy is a member-owned electric cooperative. Its 28 member cooperatives distribute electricity to about 650,000 homes, businesses, and farms in Minnesota and Wisconsin through a network of high-voltage transmission lines.

Protecting the environment has always been a priority at Coal Creek Station. John Weeda, a GRE executive says, “Our mission at GRE is to . . . provide our members with reliable, affordable wholesale power in an environmentally sound manner.” The cooperative has invested in equipment costing $200 million to clean the plant’s emissions. With this equipment, the plant has become one of the cleanest coal-fired power plants in the region.

Coal Creek Station also reduces emissions through a patented coal refining project called DryFiningTM. Since lignite contains a high percentage of water, reducing the water content of lignite increases the amount of heat (BTUs) that the coal can generate. Dryfining also reduces the amount of sulfur and mercury in the plant’s emissions by as much as 40 percent. Since 2009 when Coal Creek began using Dryfining, the plant’s overall efficiency has improved by 4 percent.

Great River Energy has found other ways to improve the efficiency of its plant by harnessing some of its by-products to new uses. The plant burns coal to produce electricity, but it the process produces excess heat. Since 2007, that heat has been re-directed to the Blue Flint ethanol plant located next to the Coal Creek power plant. Blue Flint uses waste heat from Coal Creek to process 18 million bushels of corn into 50 million gallons of ethanol each year.

Another by-product is fly ash. This is a particular type of ash that could “fly” from the smoke stacks, but GRE removes fly ash from its emissions to use in other purposes. When fly ash is added to concrete, it fills in tiny spaces and mixes with water to make a stronger, more durable concrete that can be used in buildings and highways. Fly ash can also be used to stabilize soil in erosion-prone locations.

The Coal Creek Station is a great success story. Its innovative and environmentally sound practices have brought numerous awards including two Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) awards in 2005 and 2006. Today the plant faces new challenges in the Clean Power Plan, a federal plan to reduce carbon emissions by 45 percent in coming decades.

...

Cathy A. Langemo, owner of WritePlus Inc. in Bismarck, is a writer, editor and researcher. Her true passions are genealogy, history and historical preservation.

Coal Mine Reclamation

by Cathy A. Langemo

Coal mining has been a major industry in North Dakota since the early 1900s. By the 1930s, the underground mines had closed and all mines were operated as open or strip mines. Currently, operating mines include the Dakota Westmoreland Corporation’s Beulah Mine south of Beulah, the Coteau Properties Company’s Freedom Mine northwest of Beulah, the BNI Coal Limited’s Center Mine south of Center, and the Falkirk Mining Company’s Falkirk Mine near Underwood.

Prior to 1960 little was done about reclaiming the mined lands in the state. The coal spoil piles and some structures remain today as evidence of disturbance of the earth’s surface. However, Basin Electric Power Cooperative (BE), a power supplier to electrical cooperatives in eight states, took an early interest in reclamation. The first fuel supply contracts written for BE include provisions for mine reclamation. BE was the first utility company in the U.S. to voluntarily reclaim mined land.

Today, surface mining and reclamation operations are governed by both state and federal laws. The North Dakota Legislative Assembly enacted the state’s first mine reclamation law in 1969, which became effective January 1, 1970. Between 1969 and 1977, the North Dakota Legislature passed several laws concerning reclamation. The first law required only that the spoil piles (where the mine waste was dumped) be leveled and re-seeded to grass. Later laws asked mine companies to save the topsoil and subsoil that were originally removed from the mine site and re-spread these materials in approximately the same contours the land had before mining. Since 1977, the Federal Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act have assumed federal oversight on North Dakota’s reclamation laws and enforcement.

In 1980, it cost about $5,583 to reclaim an acre of mined land, but costs continue to rise. Costs involved in reclaiming mined land include pre-mining and life-of-mine studies, mapping the landscape, mining and reclamation equipment, and fuel and maintenance services. By 2009, the cost to reclaim one acre had risen to $6,500. The cost of reclamation is applied to the cost of coal which increases the cost of generating electricity.

Reclamation requires a careful plan and mapping of the site before digging begins. The process requires proper handling of topsoil and subsoil. These two layers are removed separately, stockpiled and accurately marked for later return in their original order and location. The topsoil and subsoil layers are seeded to prevent erosion while the mining goes on. Draglines excavate remaining materials covering the coal seam. These materials, called overburden, are also preserved.

The law requires that land be returned to equal or better productivity than before mining and requires special equipment and labor, such as seeding, mulching and fertilizing. The most expensive lands to reclaim are wooded draws, with their trees, shrubs and sloped areas. Cropland is the least expensive to reclaim.

Following reclamation, former mine sites take on the appearance of the original landscape. It may take a few years for reclaimed land to mature, but North Dakota’s commitment to reclamation means that the land will continue to be productive and beautiful after mining.

...

Cathy A. Langemo, owner of WritePlus Inc. in Bismarck, is a writer, editor and researcher. Her true passions are genealogy, history and historical preservation.

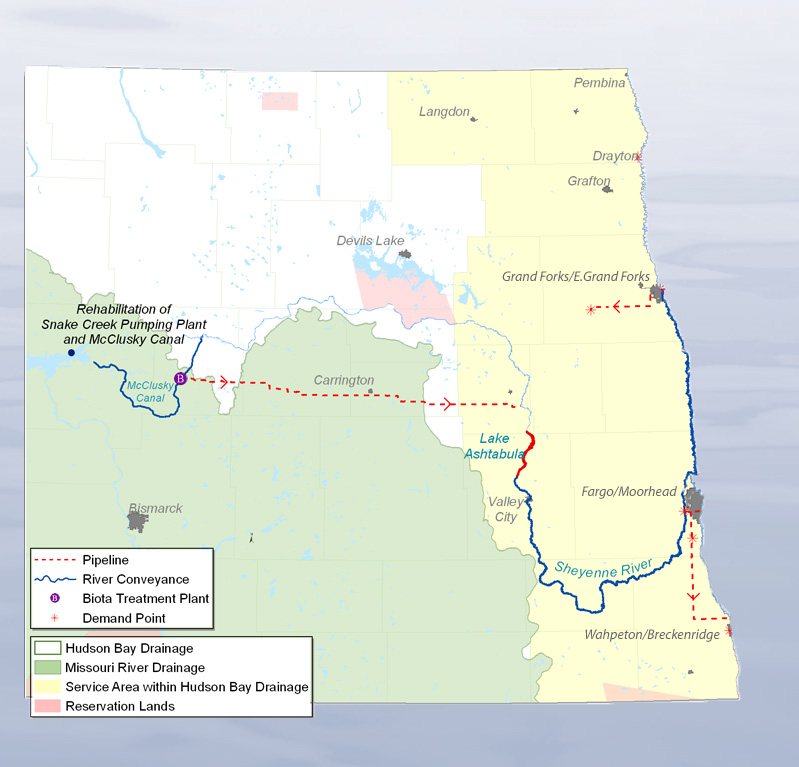

Diverting and Feeding the Red River

By Barbara Handy-Marchello

In the 1870s, the city of Fargo was sited at the perfect place. The Red River offered water for domestic, industrial, and agricultural use as well as transportation. The Red River’s tributaries – the Wild Rice, the Sheyenne, Maple, and Rush rivers – contributed to economic and population growth in the area.

The citizens of Fargo have fought many floods, but the river’s water level is unreliable in a drought. Courtesy, North Dakota State Parks

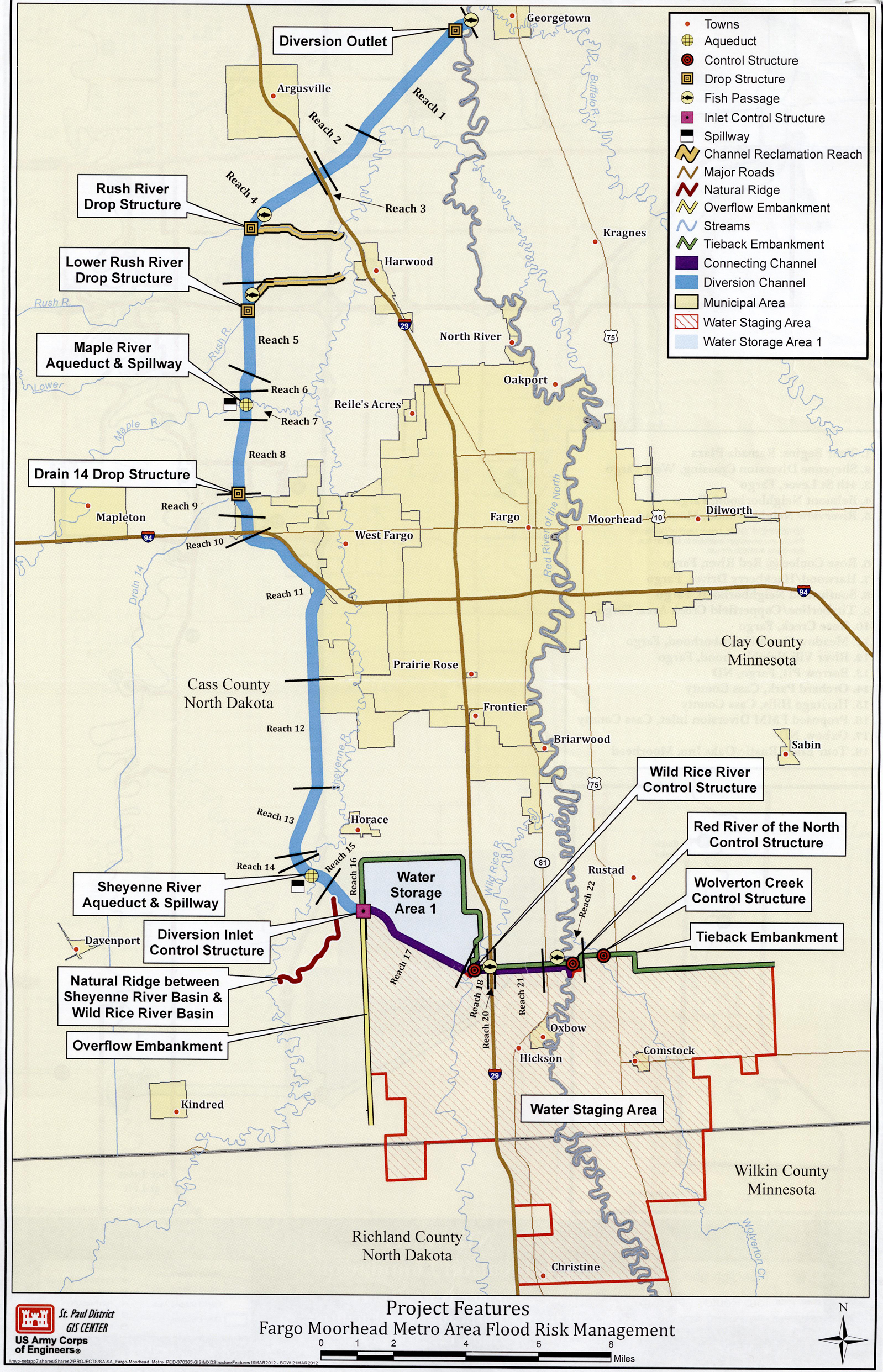

aqueducts that will be built on the west side of West Fargo. Army Corps of Engineers map

that will bring water to Lake Ashtabula. Lake Agassiz Water Authority map

Periodic flooding challenged the city’s residents and its economy. From time to time, engineers tried to find an upriver location for a dam to control floodwaters, but the shallow valley did not present a good dam site. Residents learned to cope with flooding. However, increased frequency of flooding since 1993 along with higher flood levels and the loss of flood plain to development, stirred more thinking about flood control.

The flood of 2009 crested at 41 feet and nearly inundated Fargo. Officials had to find a permanent solution to flooding. The project would require the support of the Army Corps of Engineers and involve both North Dakota and Minnesota. Engineers designed a plan for a diversion channel to take water to the west of Fargo. The Corps agreed to the plan. The cost was estimated at $1.8 billion.

Congress authorized the diversion project in 2014. The Army Corps of Engineers (ACE) expects to begin construction in 2016. In the meantime, the cities of Fargo and Moorhead have been working on a series of flood walls or levees to minimize recurring flood damage. The cities have also purchased and removed homes that were likely to be flooded. The new open space allows the river to overflow without causing damage.

The enormous cost of the project will be divided among the federal government and non-federal governments. The federal government will pay 45% ($800 million) of the cost. The remaining $1 billion will be divided among Minnesota (10% or $100 million) and North Dakota (90% or $900 million). North Dakota’s share may be divided fifty-fifty between the state and the city of Fargo in partnership with Cass County. Each would pay about $450 million. The state has appropriated $175 million as of 2016. Fargo and Cass County have approved a sales tax that will fund their portion of the costs.

The flood diversion channel will prevent flooding in Fargo, West Fargo, Harwood, and nearby housing developments. The flood of 2009 cost the city of Fargo between $40 and $50 million. In addition, 100,000 people left work or school to fight the flood. Some businesses closed or lost work costing workers their paycheck. The proponents point out that the diversion will allow the city to continue in its normal functions when the Red River rises.

There are some who oppose the diversion as it is planned. Those living upstream of Fargo (south of Fargo) have concerns about having more floodwaters than previously that would submerge farm fields, houses, roads, and cemeteries. In 2011, the ACE revealed that planned floodwater storage in fields in Richland County and southern Cass County would, indeed, add water to farm fields in a storage system that uses roads to collect and hold excess water in a major flood event. There is also some concern that once the river has been diverted, migrating fish will encounter more obstacles.

While flooding is a periodic concern for the residents of Fargo, the opposite problem may also arise. As the city grows, it will need a dependable source of water for domestic, commercial, and industrial use. The city currently relies on the Red River, but in times of drought, the water supply may not be adequate.

The Lake Agassiz Water Authority was created by the state legislature to address the need for a stable water supply for the cities and counties of the Red River Valley. The current plan is to move water from the McClusky Canal (part of the Garrison Diversion system) through a buried pipeline to Lake Ashtabula then to the Sheyenne River. The Sheyenne empties into the Red and will make adequate water available as necessary. The water will be treated as it is taken from the McClusky canal to prevent the transfer of living creatures (biota) from one water system to another.

Flood protection and water transfer will help assure growth and prosperity in Fargo and the Red River Valley for decades into the future.

...

Barbara Handy-Marchello is retired from the University of North Dakota History Department. She currently works for the North Dakota Studies program at the State Historical Society of North Dakota.

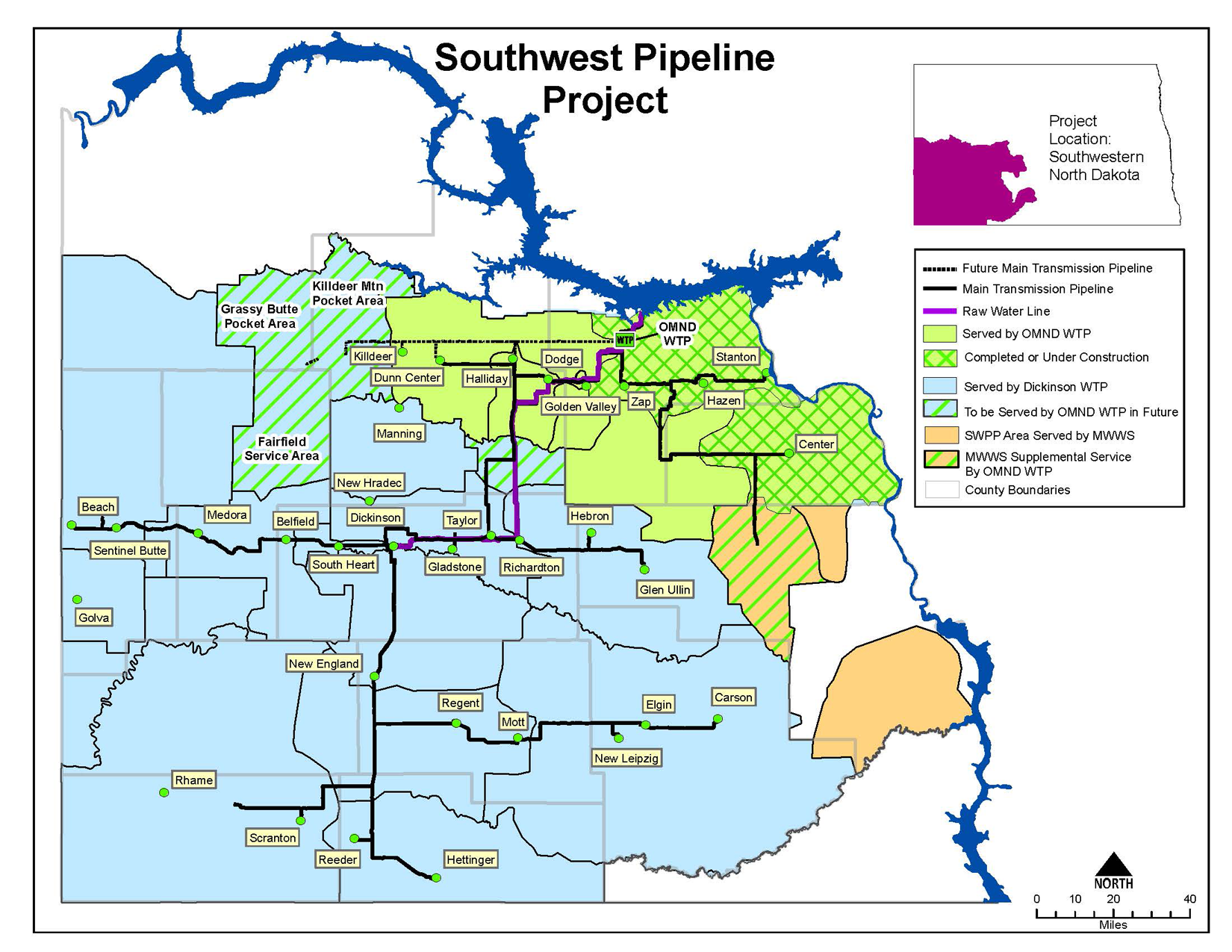

Water Lifelines

By Barbara Handy-Marchello

For decades, North Dakotans living in the 12 counties south and west of the Missouri River often drew dark, unpalatable, sometimes unsafe water from their taps. Many families purchased drinking water in town and hauled it home. Cattle sometimes refused to drink the water. Well water in the southwest portion of North Dakota was high in mineral content which corroded hot water heaters, toilets, and pipes. Brown stains made porcelain sinks and bathtubs unsightly and white clothes came out of the washer with a dark tint.

The towns and farms of southwestern North Dakota now receive good quality water from the Missouri River through these pipelines. SWA map

The operation of this system has been slowed by legal challenges from Canada. NAWS map

In 1981, the legislature funded a plan to draw water from Lake Sakakawea and deliver it to towns, rural water systems, industries, and mining operations. The plan was known as the Southwest Water Pipeline Project (SWPP). After four years of work on the design, construction began in 1986. In 1991, the legislature made a change to the SWPP by creating the Southwest Water Authority (SWA). The SWA manages the SWPP and distributes water through the pipeline to rural, industrial, and urban water users. Today, with all the legal pieces in place, the SWPP is owned by the state of North Dakota and administered by the State Water Commission through the Southwest Water Authority.

The pipeline was planned for growth. Engineers calculated water delivery potential to 150 percent of the rural users and 150 percent of the town water use in 1985. Ultimately, the growth of water demand exceeded those estimates. In 1995, the SWA sold less than 700 million gallons. In 2010, sales reached 1.6 billion gallons. The SWA expected water sales to reach 2.6 billion gallons in 2015. Much of the growth in water sales between 2010 and 2015 was related to oil development including the household water needed by oil field workers and their families.

The cost of water development is high. By 2015, the SWPP had absorbed more than $275 million. Construction of pipelines continues and the SWA is currently working on a second water intake station at Renner Bay on Lake Sakakawea.

Today, the Southwest Water Authority provides water to 58,000 residents. They live on 5,350 farms or in one of 32 communities. The water they drink is taken from Lake Sakakawea and treated at one of the water treatment plants either in Dickinson or north of Zap. A third plant is under construction. Businesses also buy raw (untreated) water from SWA which they pick up with their own trucks at water depots. One of those depots is in Dodge. Much of the raw water is used by oil fracking companies.

The Southwest Water Pipeline has brought good quality water to homes and businesses. In 2015, SWA water competed with other water suppliers in the state and won the title of “Best Tasting Water.” Competing with other states and Canadian water suppliers at Berkeley Spring, West Virginia in 2015, SWPP earned fourth place in the water taste test. SWPP water routinely ranks in the top 10 for water taste in the United States and Canada.

The Southwest Water Authority is managed by Mary Massad who notes that the SWA is a long-term project and not likely to be completed soon. Massad said, “A high-profile, high-demand project such as the SWPP will eventually be completed, but our job here at Southwest Water Authority to manage, operate, and maintain the project will never be done. . . . We must maintain and continue to implement the ND Department of Health and Environmental Protection Agency’s stringent drinking water standards, as well as continue to connect those who are still patiently waiting to receive quality water.

The Southwest Water Pipeline is not the only major water project in North Dakota. A large pipeline serving northwestern North Dakota was authorized by the state legislature in 1991 and began construction in 2002. It is known as the Northwest Area Water Supply or NAWS. The first step was to build a 45-mile pipeline from the Missouri River to Minot where the water would be treated for human consumption. This line was completed in 2009. NAWS now serves several small communities near Minot. It was a great help to communities which faced the problem of replacing aging water systems. Treated water of superior quality from Lake Sakakawea replaced water that contained high levels of iron, sodium, arsenic and other undesirable minerals. In order to meet the goals of NAWS, the Minot water treatment plant had to be upgraded.

NAWS is designed to service a project area of 81,000 people, (63,000 in urban areas). In 2013, NAWS users required about four million gallons of water per day. However, oil-driven population growth suggests a greater need than originally considered. Eventually, the NAWS project will be able to deliver a maximum of 26 million gallons per day.

NAWS, however, has been troubled and delayed by lawsuits. The Canadian Province of Manitoba sued over the movement of various kinds of biological materials (biota) from the Missouri drainage to the north-flowing Souris drainage. The Canadians believed that the transfer of biota over the two different water systems (interbasin water transfer) was not natural and possibly environmentally dangerous. U.S. courts that heard the case asked NAWS to conduct a new environmental impact statement (EIS). Multiple filters in the water pipelines were installed to prevent biota transfer.

The state of Missouri also filed a federal lawsuit over NAWS use of Missouri River water. Missouri claimed that NAWS would deplete water quantity in the river and deny Missouri its legal right to Missouri River water.

These lawsuits stopped construction for a time and the final outcome is still pending. However, about 240 miles of pipeline has already been buried and some towns such as Kenmare are already seeing benefits of the new water system.

The water pipeline projects in western North Dakota have brought excellent quality water in adequate quantities for industry, ranching, and household use to a dry country. Rick Scheid, a rancher who uses water from the Southwest Water Pipeline, appreciates the water he began to use in 2013. He said, “You can tell the water is a lot clearer and not as high in sodium. It’s good water, and I’m happy with it.”

...

Barbara Handy-Marchello is retired from the University of North Dakota History Department. She currently works for the North Dakota Studies program at the State Historical Society of North Dakota.

Sports & Outdoors

• Title IX and Girls' Sports

• The Outdoor Heritage Fund

• Private Lands Open to Hunters

• Bird Watching

• Youth Hunts

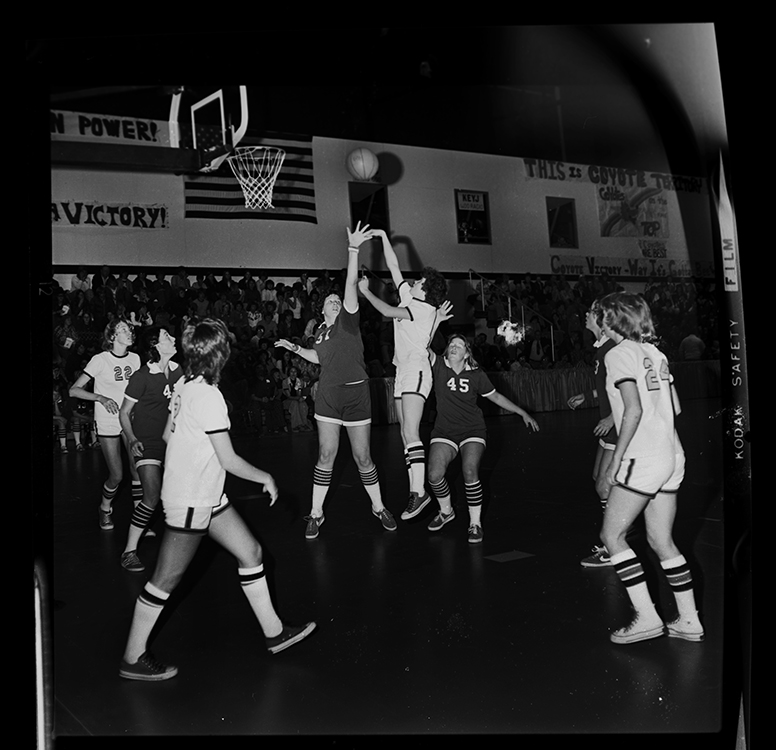

Title IX and Girls' Sports

by Cathy A. Langemo