Introduction

The cultures of Native Americans on this continent have had an impact on America. Some aspects of the lifeways and cultures of native peoples have been adapted by contemporary American society. Native peoples contributed foods, medicines, and languages to the Europeans with whom they came into contact. Pumpkins, squash, wild rice, and pemmican are examples of foods which were introduced by Native Americans. Animal names such as chipmunk, muskrat, raccoon, and caribou are all Algonquin in origin adopted by American society. Many lakes, rivers, mountains, and states have Native American names.

Traditionally, the Chippewa people were primarily a hunting and gathering society. They hunted various animals for food and clothing. They gathered berries, nuts, roots, vegetables, fruits, and wild rice for food and medicinal purposes. The Chippewa have a legend about mun-dam-in (Corn) which indicates that they were sedentary to a degree. They coexisted in harmony with nature and had a special relationship to animals evident in the structure of tribal society which centered around the clan system. Each clan is symbolized by animals. Their legends describe nature’s phenomena.

There are many factors that facilitated the transition and evolution of the Turtle Mountain people into the unique culture that exists today. The transition of the people from the woodlands to the plains vastly influenced the culture of the Turtle Mountain Chippewa. Food, transportation, clothing, and housing were all adapted to meet the needs of the people and the tribe. In addition, the blending of other cultures greatly impacted their language and lifeways from social structure and language to customs and dance.

Woodland Ways of Living

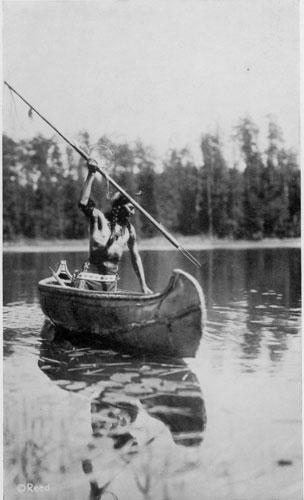

Fishing

For the Chippewa situated along the Great Lakes, the Minnesota lakes and rivers, and the Turtle Mountain lakes, fish were an abundant source of protein. Fishing was often done at night by canoeing the shallow waters and spearing fish. Torches, made of spruce pitch, lit the night waters for the fisherman and attracted the fish to the canoe. On summer nights the torches of the fishermen reflected upon the lakes and glowed for miles. Fish were trapped with basket traps, snares, wires, gill nets, and dip nets. Fish hooks were made of willow twigs. Strips of fish and meat along with berries were dried in the sun. The catch was then stored in six foot deep pits lined with dried grass and timbers. Filled with fish and other meats these pits, or caches, provided provisions for winter.

Hunting

The making of Woodland bows and arrows required a lot of time, patience, skill, and craftsmanship. Arrow shafts were made out of different types of wood depending on what was being hunted. For example, arrows that were used for the waterfowl were made of cedar because they would float. The stalks of Juneberry bushes were used mainly for making arrows. For the fetching of the arrow, feathers were utilized. Each warrior decorated his own arrows with individual markings so anyone would recognize another hunter’s arrow. Bows were made from branches of ash trees, usually four-feet long in length. The fiber used for the bowstring was made of the Stinging Nettle plant or from a material found in the neck of a snapping turtle. A perfected bow made of these materials was capable of driving an arrow completely through an animal as large as a moose.

Transportation

While living in the woodlands, the most useful form of transportation was the canoe. The Chippewa were expert craftsmen at building canoes. Birch bark was used as the outside covering for canoes. The frame was usually made from small strips of cedar wood. The outside lining of birch bark was sewed together with the root of pine trees, and covered with pitch derived from pine or balsam trees. Most traveling was done on foot through the woods, and the canoe was portaged (balanced and carried on the shoulders) from one lake to another.

Clothing

bandolier across the shoulders and used the pockets

to carry ammunition. (SHSND 870)

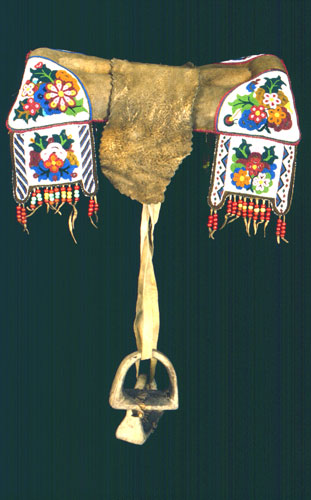

Many articles of clothing were made from the soft tanned hides of deer. The women wore dresses which were designed in two pieces. Women wore leggings that came to the knee. Jewelry was made from small pieces of leather and beads. Most dresses and other clothing articles were intricately decorated with floral designs or diamond shapes. Dyed porcupine quills were often used to decorate belts or jewelry. The women wore braids, and tied the ends with leather strips. Moccasins worn by women were similar to that of men, in that they were often decorated with quills or beadwork. During the 1800s, contact and trade with the U.S. army was established, and women began using trade blankets and calico to make dresses.

Men wore tanned hide breech clothes, leggings, moccasins, and tanned robes. The men’s leggings were worn from the ankle to the hip with a belt-type strap used to secure the leggings. The robe was replaced by army blankets when trade with the U.S. government began. Men often wore braids and fastened the ends with leather ties. The women designed ornamented buckskins for their men with beading and quill work. The tanning of hides was a task performed by the women.

Dwellings

While the tribe was basically stationary, homes varied with the season. The homes they built in the spring were made from birch bark and called wigwams. In the winter, the structural designs of the homes were dome-shaped. The exterior was insulated with snow. The floors of the wigwam were layered with woven mats of balsam branches and covered with furs.

Family Life

The people lived together in extended family units. Each group would settle in an area where their needs were best supported by the environment around them. The land was not owned, but collectively shared by those within a tribal group. The forest was always a source of game for hunting and gathering of berries or plants.

Their daily lives were guided by the seasons. With each change of the climate, a different phase of economic activity occurred. In the spring, those who had spent the winter together would set up camp near maple forests. The springtime work included the activity of maple camp or sugar making. These camps were enjoyed by all those involved in the processing and continue to operate in Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Ontario. Other nearby wintering groups would meet up and cooperate in these festive springtime activities.

Seasons

The Chippewa respect the cycle of seasons. In the fall, the tribe again split into extended family groups. Each group, consisting of about sixteen members, would hunt for a large quantity of food needed to be prepared for the winter’s rations. On these hunts, spiritual leaders went along with family groups to pray for the success of the hunt.

The winter months were spent in wigwams. Snowshoes were imperative for winter travel. But often, the blizzards, deep snow, and cold temperatures confined the families to their homes for weeks at a time. These long hours of winter darkness were spent telling stories, repairing clothes, making fish nets, preparing children for rituals, and long hours of warm, peaceful rest. (MacDonald, 1991, pp. 28-32)

Believing and Lifeways

Ways of Believing

All Ojibway people practiced the time-honored Midewewin religion. The Midewewin, Great Medicine Society, was an organization of medicine healers. The priests of the Midewewin contend that their religion began with their cultural hero Nanabozoho, the Great Hare, by order of the Great Spirit. Members of the Midewewin believe that Mother Earth is a living thing, and that all plants and animals upon her contain a spirit that is part of the Divine Creator. The Chippewa respected the cycle of seasons, the four corners of the earth, and gave thanks. Besides being a religious philosophy, the Midewewin is a practice of preserving the medicinal qualities of plants to aid the people’s longevity. (Greatwalker, 1992) See Appendix for legend of how Nanabozoho brought the Midewiwin to the people.

The ethics of the Midewewin religion are simple, yet comprised the structure of family values. Midewewin philosophy is related to nature. Tribal members lived as one with all life. They honored the “Four Orders of Creation” —physical, plant, animal, and human. Without the earth, plants, and animals, there would not be human life. The Chippewa believed they were the last form of life created on Mother Earth, and lived with respect for all life forms, often calling other forms of creation their elders. Respect was a value they honored. With the teaching of values, proper conduct was inspired. The Chippewa believed a long and balanced life was acquired through following the sacred teachings of the Midewewin.

The practice of the Midewewin instilled values to the individual and the tribe. Such characteristics as sharing, honor, and learning throughout one’s life were attributes of proper conduct. The survival of Chippewa society depended on the success of the tribe as a whole. Cooperation is an important factor to maintain safety and well-being for everyone. Individuals were encouraged to develop personal skills. Through observation, members acknowledged another’s abilities and honored them. In this way, individuals built self-esteem and a strong sense of pride in oneself and in one’s family.

Lifeways on the Plains

The Pembina Band of Chippewa began movement to the Turtle Mountains where they wintered, and eventually adapted to a Plains culture. This included the semi-annual buffalo hunt, which was a common practice of the Plains tribes. The success of the hunt was necessary for the survival of all the tribal members during winter. The Chippewa were expert buffalo hunters. Several generations of hunting and trapping conditioned the Chippewa to become expert marksmen with flintlock rifles. During these expeditions, captains were elected to carry out orders and to oversee the strategic plans. Everyone—men, women, and children—participated in the buffalo hunt. While on the plains, the tepee became the mobile home of nomadic life. This cone-like structure, made from buffalo skins, could be set up in a matter of minutes. It was easy to carry, and could be used as a year-round home. This temporary shelter was extremely important for enabling the hunter to easily move with the grazing herds. The preservation of food was also a problem. Sun-dried buffalo meat was pounded into pieces, mixed with buffalo fat, and molded into balls. Berries were sometimes added for flavor. In later years this food staple, called pemmican, became a major food source for the fur trade, and developed into an economic commodity for the Chippewa. Although the buffalo was important, the Chippewa still continued to fish the rivers and gather wild rice.

At the turn of the 19th century, the Chippewa established a settlement near Pembina. Numerous families had developed small, river-front plots into workable farms, usually around fifteen acres. It was enough to support the extended family’s needs. Gardens were grown, harvested, and traded or preserved for winter. Cattle were also raised and grazed on these family plots. Houses were made of earth (sod). Later, log cabins were the first homes built. When the Chippewa went on buffalo hunts, they continued to live in tepees made from buffalo hides.

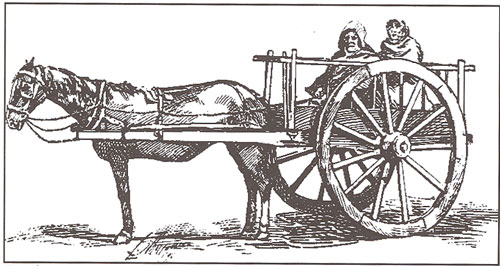

As a result of hunting and trapping in the Red River territory, a unique type of homemade horse and/or ox drawn carriage was developed by the Métis, called the “Red River Cart.” This form of transportation was well-suited for the Red River territory.

Chippewa/ Métis produced this wooden cart. The large “Red River Cart” was effective

for hauling up to 1000 pounds of supplies and rolled easily over the grass-covered prairie.

(Lounsberry, 1917, Volume 1)

Here we see lifeways being adapted to fit the needs of the people. The horse and travois had been utilized for hauling until the Chippewa/Métis produced this wooden cart. The large Red River Cart was effective for hauling up to a thousand pounds of supplies and rolling easily over the grass-covered prairies. The Red River Cart’s trails are still used today. With these carts trade between Pembina and St. Paul, Minnesota flourished. (Howe and Jelliff, pp.98–101) (Gilman et al, 1979, p. 40)

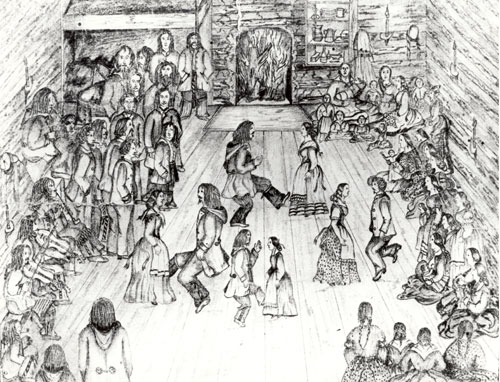

During the time the Chippewa made their home in the Red River Valley, another era of transition occurred. Lifestyles were once again modified to fit the needs of many of the people. The fiddle tune “Red River Jig” is an example of the blending of culture through music and dance. The fiddle was a strong symbol of Turtle Mountain culture for many Turtle Mountain Chippewa. The “Red River Jig” is a tune to which many people dance yet today. Fiddle music, square dancing, jigging, and contemporary country music are all forms of the French influence in dance and music expressions that are seen today.

The first mission came to Pembina in 1818 and many tribal members adopted the Catholic faith. Today, St. Ann’s, at Belcourt, is the largest Catholic parish in North Dakota.

Impact of Reservations

Surviving the early days of reservation life was a test of individual and family strength. Life was simple, yet the struggle to maintain daily needs was a constant battle. The early years of reservation life lacked an economy, agricultural means, and social programs for the hungry. The people were dependent on whatever existence they could produce. The majority of the people lived in extended family homes where parents, grandparents, and other family members resided. During the summer, large gardens were planted, cultivated, and harvested by family members. Wild berries were picked and the women canned fruits, jellies, and made syrup. Some ground and dried berries for future use. The surrounding lakes provided an abundant source of fish. People raised their own chickens, pigs, ducks, turkeys, or cattle for meat. The men and their sons still hunted for wild game including deer, moose, rabbits, and ducks. The family worked together all summer to produce enough food for the extended family to survive the winter. Since the only source of heat in the winter was from burning wood, families worked together throughout the summer to gather the winter supply. Being self-sufficient and adaptive was characteristic of the Chippewa people. Having the ability to be productive was an important family value. The Chippewas were resourceful. Bartering and trading for food and other objects of need was quite common. (St. Ann’s Centennial Book, 1985, 89-101) Baskets made of red willow were made for home use or used for barter. These baskets are unique to the Turtle Mountain Reservation.

Education

Education was an all-inclusive system which continuously reinforced a lifelong process of learning and teaching among the Chippewas. Traditionally, Chippewa children received an education from their family, clans, and extended family. The missionaries were the first to institutionalize education for the Pembina Chippewa.

Through treaties, in exchange for lands ceded, the federal government promised to provide educational services for the Chippewa. The government’s objective was designed to break down the cultures and traditions of Indian people and to urge their adoption of Western culture and economic practices.

Because the Chippewa population was growing faster than the community could accommodate, and schools and teachers were in short supply, children were sent or forced into boarding schools. Many school-age children were transported to Indian boarding schools throughout the United States where they remained for the school year. In some cases students attended boarding schools year round, for up to eight years or more, or until their course of study was complete.

Traditional ways of preparing children to learn and live in their environment were gradually eroded. Within these institutions of education, children were isolated from their families, and forbidden to speak their language or continue their cultural practices. Some children had little or no contact with their families, and as a result, strong familial bonds and family roles and other family traditions were broken and lost. These separations were brought about in many cases because of the economic and social depression of early reservation years. Parents hoped their children would be provided with consistent food, shelter, and education through the boarding school system. However, it was the intent of the government to breakdown their culture and to assimilate them into society.

The first reservation schools were small, one-room log structures, operated by the various religious orders. Boarding schools were built by the federal government and administered through agreements with religious groups. Schools operating on the Turtle Mountain Reservation were primarily run by the Catholic Church. Feelings today are mixed by those who attended boarding schools. Some believed it was a positive experience. For others, religion, rigid rules, and punishment had been imposed upon them. Some believed this practice was devastating and diminished the spiritual and traditional cultural practices which attributed to the spiritual health of native people.

In the late 1890s and early 1900, the federal government constructed several schools known as day schools on the Turtle Mountain Reservation—Greatwalker School, Dunseith Day School, Roussin School, and Houle School. The Dunseith Day School is the only remaining day school in operation. After 80 years of educational service to the community, the Dunseith Day School opened a new facility in 1993.

Day schools and boarding schools did not meet the needs of all Chippewa youth. In the l930s a plan for a consolidated school system began. In l931, a new elementary school was built. The early transportation system consisted of eight bus routes and 429 pupils. The first high school was created on the reservation beginning in 1938, when the 9th grade was added. In 1940, the next grade was added and each year thereafter until 1943 when the first high school graduation was held. That year five girls received diplomas. (St. Ann’s Centennial Book, p. 150) It was part of the Turtle Mountain Community School system which has continuously expanded, and today accommodates more than 1,800 children. In 1974, St. Ann’s, which had operated as a mission school in early reservation days, was assumed under the tribe as a contract school, and renamed the Ojibwa Indian School.

Throughout the history of educating Chippewa children, the federal government has provided assistance through various programs and pieces of legislation. The Tribal Controlled Community Colleges Assistance Act was of major importance in implementing the Chippewa’s higher educational goals. This public law authorized Congress to fund community colleges on reservations. Turtle Mountain Community College (TMCC) opened its doors in l972. It was one of the first six tribally controlled community colleges established in the nation. In l984, the college was granted full accreditation status by the North Central Association of Colleges and Schools. The college celebrated its 20th anniversary in November l992. In 2003, TMCC was renewed accreditation status as an accredited two-year community college and its success prompted community requests for movement toward a four year institution of higher education.

Flu Epidemic

During 1918 and 1919, the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa was severely hit by a flu epidemic. Many believed this flu epidemic was directly related to the end of World War I and soldiers returning from Europe. Several young men from Rolette County were either inducted or volunteered into the armed services during World War I. American soldiers returning from European duty were possible carriers of the flu epidemic. Covered wagons carried off the bodies of dead, and sometimes whole families were struck down. Devastated by death, homes that were known to have the flu were quarantined by the local police. Doctors were under contract and visited the area twice weekly. Because the reservation lacked adequate medical staff, people had to care for themselves and their sick family members. (St. Ann’s, p. 224)

Customs

Important values were taught through the family or kinship system. Each family member had specific roles and responsibilities. In the extended family, the grandparent or elders shared their knowledge and wisdom with the family. Knowledge and wisdom were learned through their life experiences. It was the responsibility of the elders and clan members to see that the young were taught the old customs, serving as teachers and role models. Parents and young adults provided the family with the necessities for survival as well as teachings. Mothers of the family were responsible for the care of the infants and for teaching of skills such as cooking, sewing, tanning, setting up of wigwams, chopping wood, and other domestic chores. Fathers of the family were responsible for teaching values and morals to the children through life experience or story telling. Fathers taught survival skills by preparing their sons for hunting and warfare. Throughout the stages of growth, children were prepared physically, mentally, spiritually, and socially for adulthood. (Warren, 87) (Kitchi Gami, pp. 276-277)

Throughout one’s life, individuals participated in many types of family and social events. During the course of one’s life an individual was instructed and prepared for each stage of life. As one stage of life was successfully completed, a time of preparation began for the next stage. One learned the value of self-sacrifice through fasting, whether it is for a vision, or a young girl entering adulthood.

Naming

As an infant, a child is usually without a name for some time. The father of the newborn child had the responsibility for giving a name. The father determined the name through observing his dreams. If unsatisfied with his dreams, he could request assistance of an elder or friend to dream the name for him. The day the name was given, the parents provided a feast for family and friends.

Puberty

Young women and men underwent initiation rites at the age of adolescence. They entered puberty. When a girl matured into womanhood, she retreated to a lodge that her mother prepared. She was secluded for four days and four nights and also fasted at this time. Sometimes a sister or other relative would bring her a small amount of food. During the first summer of her womanhood, a test of discipline and patience was achieved by forbidding her to eat fresh fruit, vegetables, or berries. Yet, she was responsible for gathering these foods for her own feast. In this way she displayed discipline and patience.

At adolescence, young men would begin fasting in an attempt to obtain a vision. The young man was left alone for several days while he fasted and prayed. If successful, the dream or vision he received was symbolic throughout his life. The dream or vision was interpreted to the young man by a circle of elders. When the young man killed his first animal, he prepared a feast. The elder interpreters were invited to the feast. The elders conducted prayers asking Kitchi Manito to bless the young man and his family.

Courtship and Marriage

The courtship of young women and men was a family event. If a young man wanted to court a young lady, he would have to present himself to the elders as he entered the lodge. After visiting with the elders of the family, he could then make his way to the center of the lodge and visit with the girl. Speaking was done in a low tone. The mother or grandmother acted as a chaperone. If the young man was sincere, he would bring the family a gift, usually of meat. If the parents accepted the gift, they were giving consent to the young man’s intentions. Then the couple was allowed to spend time together. The young couple could live with the wife’s family until they built a lodge of their own. When a young person considered marriage, they followed the unwritten law that no one could marry of the same clan. This was forbidden by society as a whole. (Densmore, 1929/1979, pp. 72-28) (Warren, p. 42)

Death and Burial Rites

In times of death certain tasks were performed for the burial. The body of the dead was washed and dressed in their finest clothing. Their hair was neatly braided and several beaded articles were left on the body. The face of the dead was painted brown. The blanket and moccasins were also streaked with brown paint. Articles that were significant in that person’s life were placed with the body. Articles such as a tobacco pouch, medicine bundle, or pipe, could be placed with the deceased. The Chippewa believed this was the last journey so only provisions for a few days were left with the dead. They believed that the hereafter would provide all. The Midewewin priest performed a last ceremony for the deceased. On the fourth day after death, the body was wrapped in birch bark and secured with strips of basswood cord. The body was placed in a shallow grave with the feet pointed toward the west. The direction west represented the direction of the spirit’s journey. Mourning was made evident by the appearance of the person mourning. Sometimes the hair was cut short, or if left long, they let it hang freely without braids or ties. They wore shabby clothes and avoided social events.

The drum is used by the Chippewa for spiritual and social gatherings. Tobacco continues to be used in many spiritual rituals. It is used as an offering to Kitchi Manito in prayers and is used when taking something of the earth for food or medicine. Sage, sweet grass, and cedar are used in ceremonies. Eagle feathers are used in many ceremonies and are symbols of honor. (Mishomis, pp. 80-82) The pipe is an important part of the Midewewin. It is used as a symbol of peace for all tribes and nations. See Appendix for legend which tells how the Ojibway received the pipe.

Modern Culture

Culture in Transition

Cultural Renaissance

In 1883, Secretary of the Interior Henry M. Teller, with the support of some Christian religious organizations, established a “Court of Indian Offenses,” which forbade all public and private traditional religious and cultural activities such as the Sun Dance. The Sun Dance was widely practiced after the Chippewa moved to the plains. Although the Sun Dance and other religious practices were forbidden, and punishment for such conduct was severe, the Sun Dance was a yearly event at Turtle Mountain until 1904. Thereafter, it was held secretly. Religious freedom was not fully restored until Congress passed the Religious Freedom Act in 1978. For the first time in almost 100 years, native people were given the same religious freedoms enjoyed by other American citizens.

As traditional societies evolve and change, so have the Turtle Mountain Chippewa. A time of individual religious freedom is being restored. Although the majority of the Turtle Mountain Chippewa are of the Catholic faith, growing numbers of people are practicing traditional ceremonies. Today you may see a traditional ceremony at a funeral, marriage, blessings, graduations, and inaugurations. The people are entering a time of revived interest in tribal teachings. Elders who have preserved traditional customs, and who have maintained spiritual and cultural practices, are passing on these practices through modeling and through oral history. Many young people are exploring their ancestral roots. Today there is a rediscovery of what was lost, taken away, and forbidden.

The Culture Today

St. Ann’s Day

A gathering of spiritual unity, prayer, and healing takes place during the last week in July. For more than a hundred hears on the Turtle Mountain Reservation, the Catholics have celebrated this annual celebration in honor of their patron, Saint Ann. The people’s faith and its origin are eloquently expressed by the “Centennial Poem,” which can be referenced in the Appendix. The dedication to St. Ann’s Day celebration is evident in the community involvement. Many people who are enrolled members but live off the reservation, return home yearly to participate in the St. Ann’s Day activities.

“La Bonne Anee”

New Year’s, “La Bonne Anee” (we are looking for a better year), a French word for saluting the New Year, is a special celebration that is enjoyed by the Turtle Mountain Chippewa. It is a time of feasting, dancing, singing, and socializing. In a narrative written about the Chippewa Christmas and New Year celebrations on the Turtle Mountain Reservation, the following description was provided:

The New Year Celebration is one that has been practiced since the era of French influence in the 1800s. Years ago, this event began on New Year’s Eve and extended until January 6th, All Kings Day (if a baby boy was born on January 6th, King was added to his name). If you stood outside, you could hear sleigh bells ringing through the cold night air as families gathered at the homes of their elders (parents or grandparents). Traditionally they would go from house to house to toast the New Year, and enjoy the feast. Upon arrival to someone’s home you can hear the expression “La Bonne Anee,” and receive a kiss and a handshake from everyone in the house young and old. The custom of kissing and shaking hands is an expression of good wishes for the coming year . . . The feast included foods such as le’ boulete (ground beef made into meatballs, rolled in flour and boiled), bangs (fried bread dough), flat galette (a flattened bread), potatoes, pork, confitre —berries in sauce, beef, turkey, homemade pies, (touquiere pie—a ground pork meat pie served with cranberries, and pouchin (boiled cake). (Memories of Christmas and New Years on the Turtle Mountain Reservation. Bercier, M., Laverdure, P. and Davis, R., Culture Department, Turtle Mountain Community School, 1975—In part from an interview with Fox, Irene, 1994, August)

Besides feasting, there would be square dancing, jigging to fiddle music, and the singing of French songs. Furniture would be pushed out of the way so that the dancing could begin. This tradition of going from house to house, to feast and party, is still practiced today. Although the celebration no longer continues until the 6th of January, family and friends make their rounds on New Year’s Eve and New Year’s Day. Usually the eldest female within a family prepares the meal. Friends and family members start arriving around midnight, and the flow of visitations continues until midnight on New Year’s Day.

Annual Social Events

The Powwow (Pauwaw, Pauwau)

The concept of the pow-wow has always been misunderstood. The first (American Indian) word Europeans associated with Indian dancing was the Algonquin word pau wau. The Algonquin definition actually referred to Medicine Men and Spiritual leaders and meant “He Dreams.” When the Europeans first saw the natives dance, they believed that all dances were referred to as Pau wau. This term was eventually accepted as a collective term by the Europeans to refer to dancing. A form of this word is still used today.

Today, many members of the Turtle Mountain Band follow the pow wow circuit. Pow wows are usually about three-day events. These annual celebrations are a time of dancing, singing, feasting, praying, teaching, learning and laughing. This time is considered to be a time of remembering the past, the old ways, and also a time of dreaming for the future. Area residents travel throughout the United States and Canada, participating in these events. Annual celebrations locally include the Little Shell Pow Wow, New Year’s Eve Pow Wow, Turtle Mountain Community College Graduation Pow Wow, Mother’s Day Pow Wow, School Club Pow Wows, and Veterans Day Pow Wow.