The first supporting question, “How did early peoples on the northern Great Plains keep track of time?” helps students use sources to unwrap the context of the topic being examined. Who are the indigenous people that have lived on the northern Great Plains for thousands of years, and how do they think about time? Native Americans used astronomical knowledge to mark time, and seasonal changes had a huge influence on their lives. The Lakota and other tribes kept track of the passage of time and their community history using winter counts (waniyetu wowapi). The annual season was reckoned from the first snow of one winter to the first snow of the next winter.

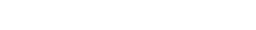

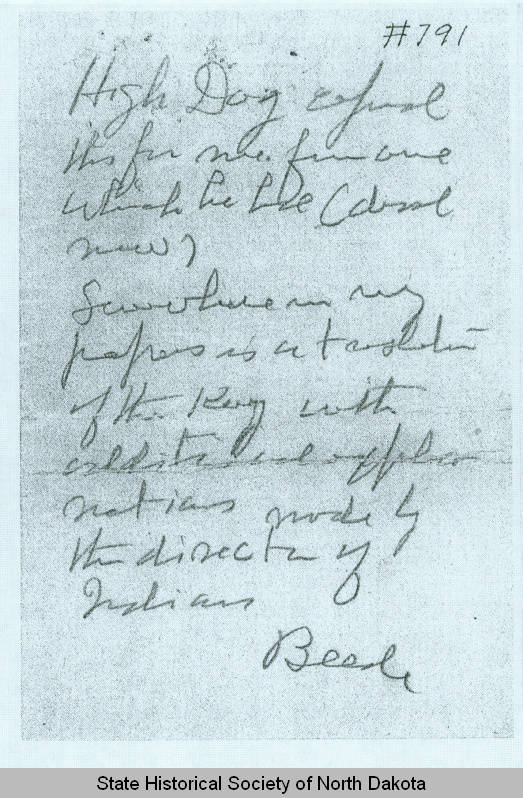

This inquiry includes two winter counts. The count by John No Ears was collected by Major General Hugh Scott, who worked for the Bureau of American Ethnology. High Dog’s winter count was collected in 1912 by Aaron Beede, an Episcopalian missionary to the Lakota. John No Ears’ count, which perhaps followed an older tradition, probably did not include a pictograph. Pictographic winter counts such as High Dog’s used a single image painted on hide, and later, muslin or paper, to remind the keeper of the major events and their importance. The events used to mark the passage of years were kept in the memory of the keeper of the winter count and served as a mnemonic (or mnemographic) device. The keepers chose significant events after consulting with the elders and leaders of his band or village.

The Lakota were not the only tribe to keep winter counts in either an oral tradition or with pictographs painted on hide, muslin, or paper. However, many surviving counts were collected on Lakota reservations. The Lakota were interesting to missionaries, traders, army officers, and government agents because of their long resistance to white dominance and their involvement in the Battle of the Little Big Horn. Because of the large population of Lakota and the great numbers of white people interested in their communities, Lakota counts survived dislocation and loss of tradition. While many Lakota traditions, such as the Sun Dance, were outlawed, the winter count was not, so many winter counts continued into the twentieth century. Complete the following task using the sources provided to build a context of the time period and topic being examined.

Formative Performance Task 1

Create a graphic organizer that identifies milestones in your life and an image or symbol to represent each. Use the graphic organizer to create a poster or timeline that represents major events in your life.

Featured Sources 1

The sources featured below are primary sources. They are the raw materials of history—original documents, personal records, photographs, maps, and other materials. Primary sources the first evidence of what happened, what was thought, and what was said by people living through a moment in time. These sources are the evidence by which historians and other researchers build and defend their historical arguments, or thesis statements. When using primary sources in your lessons, invite students to use all their senses to observe, describe, and analyze the materials. What can they see, hear, feel, smell, and even taste? Draw on students’ knowledge to classify the sources into groups, to make connections between what they observe and what they already know, and to help them make logical claims about the materials that can be supported by evidence. Further research of materials and sources can either prove or disprove the students’ argument.

The sources featured below are primary sources. They are the raw materials of history—original documents, personal records, photographs, maps, and other materials. Primary sources the first evidence of what happened, what was thought, and what was said by people living through a moment in time. These sources are the evidence by which historians and other researchers build and defend their historical arguments, or thesis statements. When using primary sources in your lessons, invite students to use all their senses to observe, describe, and analyze the materials. What can they see, hear, feel, smell, and even taste? Draw on students’ knowledge to classify the sources into groups, to make connections between what they observe and what they already know, and to help them make logical claims about the materials that can be supported by evidence. Further research of materials and sources can either prove or disprove the students’ argument.

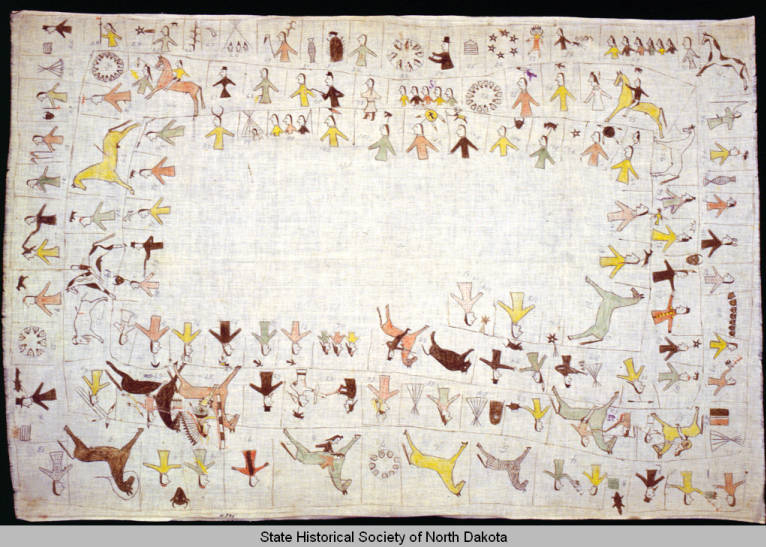

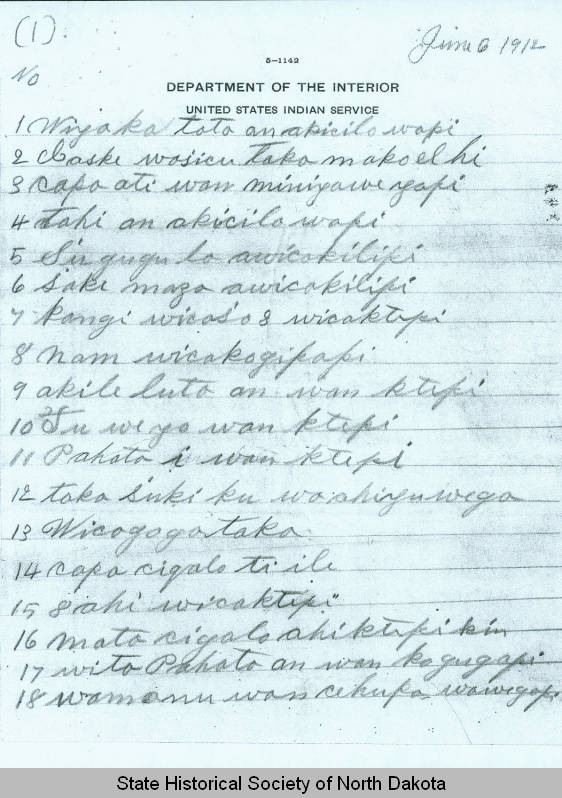

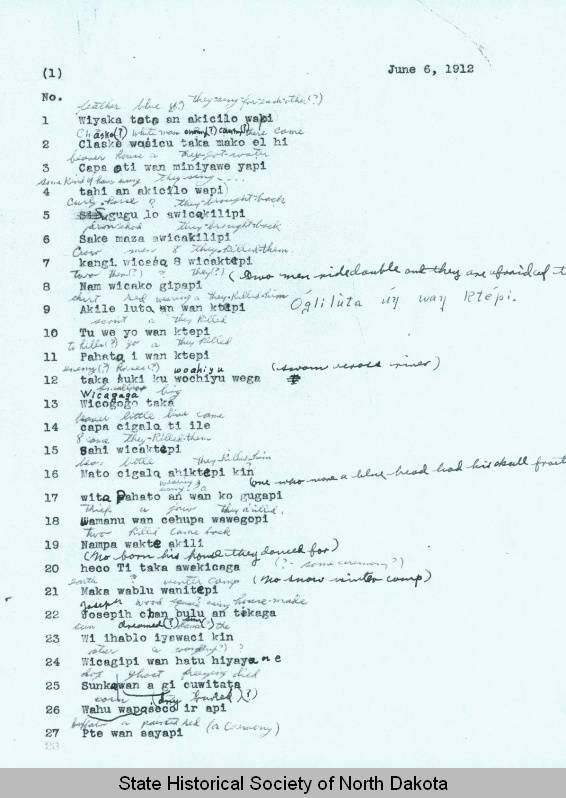

Read Reverend Beede's different versions of High Dog’s winter count from the original handwritten list to the final, fuller, description. How does Reverend Beede's understanding grow as he works through the process of recording, translating, and discussing the pictograph? Beede’s careful process of collecting the terms, translating them, then completing the telling with a longer explanation of the events offers a detailed understanding of Lakota life on the northern plains during a period of cultural transition as well as the influence of the collector (in this case Reverend Beede) on the story-telling process. Other collectors influenced winter counts by requesting copies or purchasing them. What more can you learn about Reverend Aaron Beede, Major General Hugh L. Scott, High Dog, and John No Ears? These men have very different backgrounds and reasons for creating and collecting winter counts. Does that make a difference in the way we understand Lakota history? Identify specific information that supports your findings.

Historians corroborate past events by checking other sources. Can you verify some of High Dog's observations? For instance, 1910 indicates a comet. Was there a comet in 1910? Was there another one in 1912? What else can you learn about 1833 the Year the Stars Fell? What more can you find out about the captivity of Mrs. Fanny Kelley (number 67)? Why did High Dog and other sources refuse to elaborate on some of the glyphs (as in number 83)? Can you match any of the events in John No Ears' count and High Dog's count to each other? What conclusions can historians and other researchers draw from these different accounts?

| Source A |

High Dog Count

High Dog was the keeper of this winter count, but he probably did not start either the pictograph or the count, which likely began before 1798. He might have inherited the role of winter count keeper or might have purchased the right to it. In either case, the keeper would have chosen the symbol for the year after consulting with the leaders and elders of the tribe. The winter counts demonstrate not only the method of remembering the history of a people, but of the cultural transition that took place during the 19th century. Beede described the economic importance of the winter count and other artifacts of the Lakota past in his letter (dated June 9, 1917) to State Historical Society of North Dakota Museum curator Melvin Gilmore. Beede purchased items from Lakota men and women including High Dog's winter count for which he paid $8.00. Today, its value is beyond reckoning because of its explanation of the Lakota past. SHSND Museums 791. http://www.digitalhorizonsonline.org/digital/collection/uw-ndshs/id/3134 |

| Source B |

Aaron McGaffey Beede.

SHSND C0295. |

| Source C |

Beede’s Handwritten Account of the High Dog Winter Count

http://www.digitalhorizonsonline.org/digital/collection/uw-ndshs/id/3135 |

| Source D |

Beede’s Typed Transcript of His Handwritten Account

http://www.digitalhorizonsonline.org/digital/collection/uw-ndshs/id/3135 |

| Source E |

Beede’s Account Typed and Translated From Lakota to English

http://www.digitalhorizonsonline.org/digital/collection/uw-ndshs/id/3137 |

| Source F |

Key to the High Dog Winter Count, Expanded by Interviews with Native Americans

http://www.digitalhorizonsonline.org/digital/collection/uw-ndshs/id/3138 |

| Source G |

John No Ears’ winter count does not have a pictograph (Greene and Thornton, 2007: 45). This typescript copy was apparently typed by State Historical Society of North Dakota museum curator Melvin R. Gilmore from the original written recorded by Major General Hugh L. Scott. Gilmore’s notes are signed M.R.G. Though Scott’s interpretation is not as thorough as Beede’s, this count has the advantage of having the Dakota words printed along with the English translation. Many events signifying Lakota history in No Ears’ count can be corroborated with High Dog’s winter count. SHSND Mss 20167. |