The first supporting question, “For what reasons were the U.S. military initially sent to the northern Great Plains?” helps students use sources to unwrap the context of the time and topic being examined. Who were the tribal nations living in Dakota Territory in the mid-19th century? How did they think about the land? Where did they live? What else was going on? Northern Dakota Territory was the scene of intense armed conflict between the Army and various bands of Lakota and Dakota (Oceti Sakowin) between 1863 and 1864. Much of this conflict related to the outbreak of war between the Mdewakanton and Wahpekute Dakota and European American residents of south-central Minnesota known as the US-Dakota Conflict of 1862. Some of the Dakota fled seeking refuge in northern Dakota Territory. Henry Hastings Sibley led the army in pursuit and engaged Native Americans in skirmishes and battles several times in 1863. Most of the Native Americans Sibley engaged with had not participated in the Dakota War and were not hostile toward the army. Then General Alfred Sully joined the pursuit, leading mounted troops up the Missouri River from Yankton. Sully’s troops turned east following a large band of Indian families who were preparing to hunt buffalo along the James River. On September 3, 1863, Sully learned of the camp at Whitestone Hill. He attacked, killing men, women, and children, and taking many more captive. Sully then ordered his men to destroy the tipis, food supplies, and other goods left behind by the fleeing survivors. This period of conflict led to the construction of several army posts beginning with Sully’s Fort Rice in 1864 on the western bank of the Missouri River (30 miles south of present-day Mandan.) Marching from Fort Rice on July 28, 1864, Sully attacked Teton and Yanktonnais (Oceti Sakowin) in the Killdeer Mountains. There was another encounter in the badlands along the Little Missouri River.

Sibley’s and Sully’s expeditions were supposed to punish the Dakota, but by attacking all the Indians they found, whether they were preparing for war or not, they generated ill-will that led to heightened hostilities. Some of the Indians pursued by Sibley attacked a boat full of gold miners returning from the gold mines in July 1863; others besieged a wagon train heading for the Montana gold fields at Fort Dilts in present-day Bowman County in September 1864. Complete the following task using the sources provided to build a context of the time period and topic being examined.

Formative Performance Task 1

Write a summary or outline of why the U.S. government initially sent the military to Dakota Territory. Set the stage for what was going on both in the region and in the United States. What time frame did this happen in? What else was going on? What were the major newspaper headlines (both locally and nationally)? What was going on that people were concerned about? Write a short summary to highlight the reasons the military was sent to the northern Great Plains at this time.

Featured Sources 1

The sources featured below are primary sources. They are the raw materials of history—original documents, personal records, photographs, maps, and other materials. Primary sources the first evidence of what happened, what was thought, and what was said by people living through a moment in time. These sources are the evidence by which historians and other researchers build and defend their historical arguments, or thesis statements. When using primary sources in your lessons, invite students to use all their senses to observe, describe, and analyze the materials. What can they see, hear, feel, smell, and even taste? Draw on students’ knowledge to classify the sources into groups, to make connections between what they observe and what they already know, and to help them make logical claims about the materials that can be supported by evidence. Further research of materials and sources can either prove or disprove the students’ argument.

Read featured sources A-L. In a group or as a class, answer the following questions: What type of sources are they (letters, photos, maps, diaries, etc.)? What kind of information do they contain? Who created each of these sources? Who was the intended audience for each source? Why were these sources created? When were the sources created? What do the sources tell us about Dakota Territory during that time? How do we know? What else can you find? Study these sources to evaluate where the different accounts agree or contradict each other. Do they all include the same type of data? When and where did the conflict take place? What was the reason for the battle? How many people participated in the conflicts described? How many women and children were there? Why might people have different versions of the same event? What conclusions can historians and other researchers draw from these different accounts? Identify specific sentences that support your findings.

The Battle of Heart River

In the early 1860s, gold was discovered in the mountains of Montana and Idaho. The Missouri River was the main travel corridor for miners going to and returning from Montana. In July 1863, a Mackinaw boat carrying a couple dozen miners and at least one family was returning from the gold fields, apparently with some amount of gold dust and nuggets on board. While many of the details are not clear, it appears that the miners came into conflict with some Lakota who were camped near the Missouri River opposite the mouth of the Heart River. All the miners were killed in the battle and their boat sank. How the battle started, how many participated, how many were killed, and what happened to the gold dust on board the boat are details that differ depending on the perspective of those who participated.

This battle reveals the extent of conflict in this two-year period in North Dakota’s history. Though there were few settlers in the northern part of the territory at that early date, those traveling through were subject to the anger of Native American people who were being harassed by the army and had suffered major losses due to Sully’s policy of destroying household and personal goods, and food supplies after a battle. The battle of the Heart River was an important element in Sully’s decision to push eastward and attack the first Indian camp he found. In his report, he notes that gold dust in the possession of Indians on the battlefield justified his attack.

The sources featured below are primary sources. They are the raw materials of history—original documents, personal records, photographs, maps, and other materials. Primary sources the first evidence of what happened, what was thought, and what was said by people living through a moment in time. These sources are the evidence by which historians and other researchers build and defend their historical arguments, or thesis statements. When using primary sources in your lessons, invite students to use all their senses to observe, describe, and analyze the materials. What can they see, hear, feel, smell, and even taste? Draw on students’ knowledge to classify the sources into groups, to make connections between what they observe and what they already know, and to help them make logical claims about the materials that can be supported by evidence. Further research of materials and sources can either prove or disprove the students’ argument.

Read featured sources A-L. In a group or as a class, answer the following questions: What type of sources are they (letters, photos, maps, diaries, etc.)? What kind of information do they contain? Who created each of these sources? Who was the intended audience for each source? Why were these sources created? When were the sources created? What do the sources tell us about Dakota Territory during that time? How do we know? What else can you find? Study these sources to evaluate where the different accounts agree or contradict each other. Do they all include the same type of data? When and where did the conflict take place? What was the reason for the battle? How many people participated in the conflicts described? How many women and children were there? Why might people have different versions of the same event? What conclusions can historians and other researchers draw from these different accounts? Identify specific sentences that support your findings.

The Battle of Heart River

In the early 1860s, gold was discovered in the mountains of Montana and Idaho. The Missouri River was the main travel corridor for miners going to and returning from Montana. In July 1863, a Mackinaw boat carrying a couple dozen miners and at least one family was returning from the gold fields, apparently with some amount of gold dust and nuggets on board. While many of the details are not clear, it appears that the miners came into conflict with some Lakota who were camped near the Missouri River opposite the mouth of the Heart River. All the miners were killed in the battle and their boat sank. How the battle started, how many participated, how many were killed, and what happened to the gold dust on board the boat are details that differ depending on the perspective of those who participated.

This battle reveals the extent of conflict in this two-year period in North Dakota’s history. Though there were few settlers in the northern part of the territory at that early date, those traveling through were subject to the anger of Native American people who were being harassed by the army and had suffered major losses due to Sully’s policy of destroying household and personal goods, and food supplies after a battle. The battle of the Heart River was an important element in Sully’s decision to push eastward and attack the first Indian camp he found. In his report, he notes that gold dust in the possession of Indians on the battlefield justified his attack.

Whitestone Hill

Whitestone Hill State Historic Site, located 23 miles southeast of Kulm, Dickey County, marks the scene of the fiercest clash between Native Americans and U.S. soldiers in North Dakota. On September 3, 1863, General Alfred Sully's troops attacked a tipi camp of Yanktonai, some Dakota, Hunkpapa Lakota, and Blackfeet (Sihasapa Lakota), as part of a military mission to punish participants of the US-Dakota Conflict of 1862. Many Indian men, women, and children died or were captured. Military casualties were comparatively light. The Indians also suffered the destruction of virtually all of their property, leaving them nearly destitute for the coming winter. Learn more about the history of Whitestone Hill.

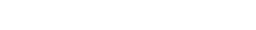

| Source F |

General Alfred Sully

Source: SHSND 10548-VOL3-00006. |

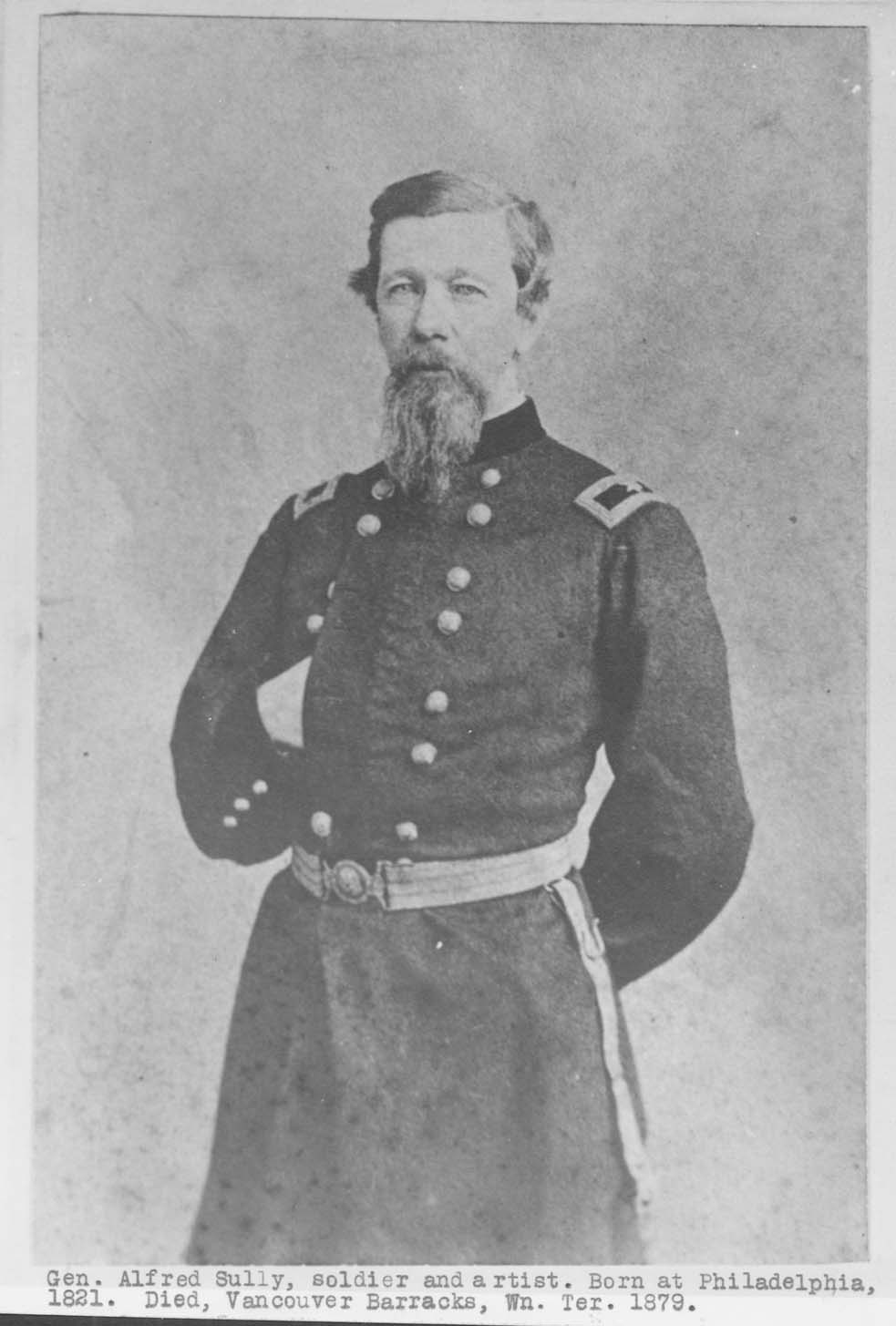

| Source G |

An artist's view of the cavalry charge of General Sully's brigade at the battle of Whitestone Hill. Source: SHSND 10548-VOL1-00003. |

| Source H |

From Sully’s Official Report on the Battle of Whitestone Hill Major House, according to my instructions, endeavored to surround and keep in the Indians until word could be sent me; but this was an impossibility with his 300 men, as the encampment was very large, mustering at least twelve hundred warriors. This is what the Indians say they had, but I, as well as everybody in the command, say they had over fifteen hundred. These Indians were partly Santees from Minnesota; Cutheads from the Coteau; Yanktonnais, and some Blackfeet who belong on the other side of the Missouri. And as I have since learned, Uncapapas, the same party who fought General Sibley and destroyed the Mackinaw boat. Of this I have unmistakable proof from letters and papers found in the camp and on the person of some of the Indians, besides relics of the late Minnesota massacre; also from the fact that they told Mr. LaFromboise, the guide, when he was surrounded by about two hundred of them, that ‘they had fought General Sibley, and they could not see why the whites wanted to come to fight them, unless they were tired of living and wanted to die.’ Mr. La Fromboise succeeded in getting away from them after some difficulty, and ran his horse for more than ten miles to give me information. ...He reached me a little after 4 o’clock. I immediately turned out my command. The horses at the time were out grazing. At the sound of the bugle the men rushed with a cheer, and in a very few minutes saddled up and were in line. I left four companies and all the men who were poorly mounted in the camp, with orders to strike the tents and corral all the wagons, and starting off with the Second Nebraska on the right, the Sixth Iowa on the left, one company of the Seventh Iowa and the battery in the center, at a full gallop, we made this distance of over ten miles in much less than an hour. The Battle On reaching near the ground I found that the enemy were leaving and carrying off what plunder they could. Many lodges, however, were still standing. I ordered Col. W. R. Furnas, Second Nebraska, to push his horses to the utmost, so as to reach the camp and assist Major House in keeping the Indians corralled. This order was obeyed ..., the regiment going over the plains at a full run.... The Nebraska took to the right to the camp, and was soon lost in a cloud of dust over the hills. I ordered Col. D. S. Wilson, Sixth Iowa, to take to the left, while I, with the battery, one company of the Seventh Iowa, Captain A. J. Millard, and two companies of the Sixth Iowa, Major TenBroeck commanding, charged through the center of the encampment. I here found an Indian chief by the name of Little Soldier, with some few of his people. This Indian has always had the reputation of being a good Indian and friendly. I placed them under guard and moved on. Shortly after I met with the notorious chief, Big-Head, and some of his men. They were dressed for a fight but my men cut them off. These Indians, together with some of their warriors, mustering about thirty, together with squaws, Indian ponies, and dogs, gave themselves up, numbering over one hundred and twenty human beings. About the same time firing began about a half mile ahead of me, and was kept up, becoming more and more brisk until it was quite a respectable engagement. A report was brought to me, which proved to be false, that the Indians were driving back some of my command. I immediately took possession of the hillocks near by, forming a line, and placing the battery in the center on a higher knoll. At this time night had about set in, but still the engagement was briskly kept up, and in the melee, it was hard to distinguish my lie from that of the enemy. The Indians made a very desperate resistance, but finally broke and fled, pursued in every direction by bodies of my troops. I would here state that the troops, though mounted, were armed with rifles, and according to my orders, most of them dismounted and fought afoot until the enemy broke, and when they remounted and went in pursuit. It is to be regretted that I could not have had an hour or two more of daylight, for I feel sure, if I had, I could have annihilated the enemy. As it was I believe I can safely say I gave them one of the most severe punishments the Indian have ever received. After night set in the engagement was of such a promiscuous nature that it was hard to tell what results would happen; I therefore ordered all the buglers to sound the ‘rally,’ and building large fires, remained under arms during he night, collecting together my troops. The next morning early I established my camp on the battlefield; this was the 4th [of September], the wagon train under charge of Major Pearman, Second Nebraska, having in the night been ordered to join me, and sent out strong scouting parties in different directions to scour the country to overtake what Indians they could, but in this they were not very successful, though some of them had some little skirmishes. They found the dead and wounded in all directions, some miles from the battlefield; also immense quantities of provisions, baggage, etc., where they had apparently cut loose their ponies from ‘travois,’ and go off on them; also large number of ponies and dogs, harnessed to ‘travois,’ running loose on the prairie. One party that I sent out went near to the James River, and found there eleven dead Indians. The deserted camp of the Indians together with the country all around, was covered with their plunder. I devoted this day together with the following [day], the 5th, to destroying all this property, still scouring the country. I do not think I exaggerate in the least when I say that I burned up over four hundred thousand to five hundred thousand pounds of dried buffalo meat as one item, beside 300 lodges, and a very large quantity of property of great value to the Indians. A very large number of ponies were found dead and wounded on the field; besides a large number was captured. The prisoners, some one hundred and thirty, I take with me below, and shall report to you more specially in regard to them. Kingsbury, pp. 293-294. |

| Source I |

Kingsbury The following historical report on the Battle of Whitestone Hill was written by George Kingsbury in History of Dakota Territory Vol 1 (Chicago: The S. J. Clarke Publishing Company, 1915), 289-290. Sully’s fighting force numbered about fifteen hundred men and he had reduced his wagon transportation to seventy-five. In fifteen days he had reached Long Lake Creek. Here Sully learned from an old decrepit Indian, that was found on the prairie, that Sibley had met the Indians only a short distance from the camp, and a detachment of troops were at once dispatched to ascertain whether the old Indian’s narrative was reliable. The detachment found Sibley’s camp and the battle field just as described and learned further that the Indians had been driven [west] across the Missouri, but had recrossed three days after Sibley left, opened the caches where their goods were stored, and had gone east probably to overtake and harass Sibley’s rear. Sully immediately started in pursuit. This was on the 1st of September, and on the 3d, late in the afternoon, his scouts discovered one encampment of eight hundred to one thousand hostiles. The troops were then hurried forward, leaving a suitable guard for the supply train, and after a sharp ride of eight miles came upon a recently deserted Indian camp, the occupants having fled upon the approach of the troops; another mile brought the fugitive in full view; the troops galloped forward, and the battle opened without any formalities, our soldier pouring in a deadly fire upon the enemy, which was valiantly returned. The Indians appeared to the soldiers in the twilight of evening as a dark struggling mass of beings, yelling, shouting, shooting and groaning. The Indians were now mainly concentrated in a narrow ravine, quite shallow, each side of which was flanked by the troops, who kept up a galling and destructive fire as long as it was possible to distinguish an Indian from a soldier. Orders then came to cease firing fearing the troops might fire into their own ranks, so intense was their fighting ardor, and the men bivouacked on the field. At daylight the following morning Sully expected to resume the battle but the enemy had quietly faded away during the night, abandoning everything that would impede his flight. The battlefield presented a soul-sickening sight. All the slain soldiers, nineteen in number, were horribly mangled and scalped, some of them tomahawked, indicating that they had been helplessly wounded, and some killed with the merciless hatchet during the night. Intermingled with our dead were the bodies of the Indians and horses, all a ghastly field to look upon, while for miles were tepee poles, folded lodge skins and thousands of packs of dried buffalo meat. No attempt was made to follow the fugitives, as they had evidently scattered in every direction, but a scouting party was sent out as a measure of precaution, and during the day Big Head, the chief, was captured and a large number of squaws and children and quite a number of braves. This scouting party was surprised on one occasion by running into a numerous body of fugitives, who came very near surrounding them, and were able to kill four of the cavalrymen before the captain was able to extricate his command from its perilous situation. Sully had lost twenty-three in killed and thirty wounded, one of the wounded of the Nebraska Second dying a little later. A force of 200 men was detailed to gather up and burn the abandoned supplies of the Indians, saving what was necessary to subsist and shelter the Indian prisoners. Two entire days were consumed in this work, which shows the large quantity of stores, lodges, etc., destroyed. Sully estimated that the Indian loss would reach one hundred and fifty as learned from his prisoners, and the wounded were much more numerous. |

| Source J |

From Colonel Furnas’ Official Report The Indians are now destitute of supplies, clothing, and almost everything else, they having abandoned all except their clothing and arms. Kingsbury, p. 296. |

| Source K |

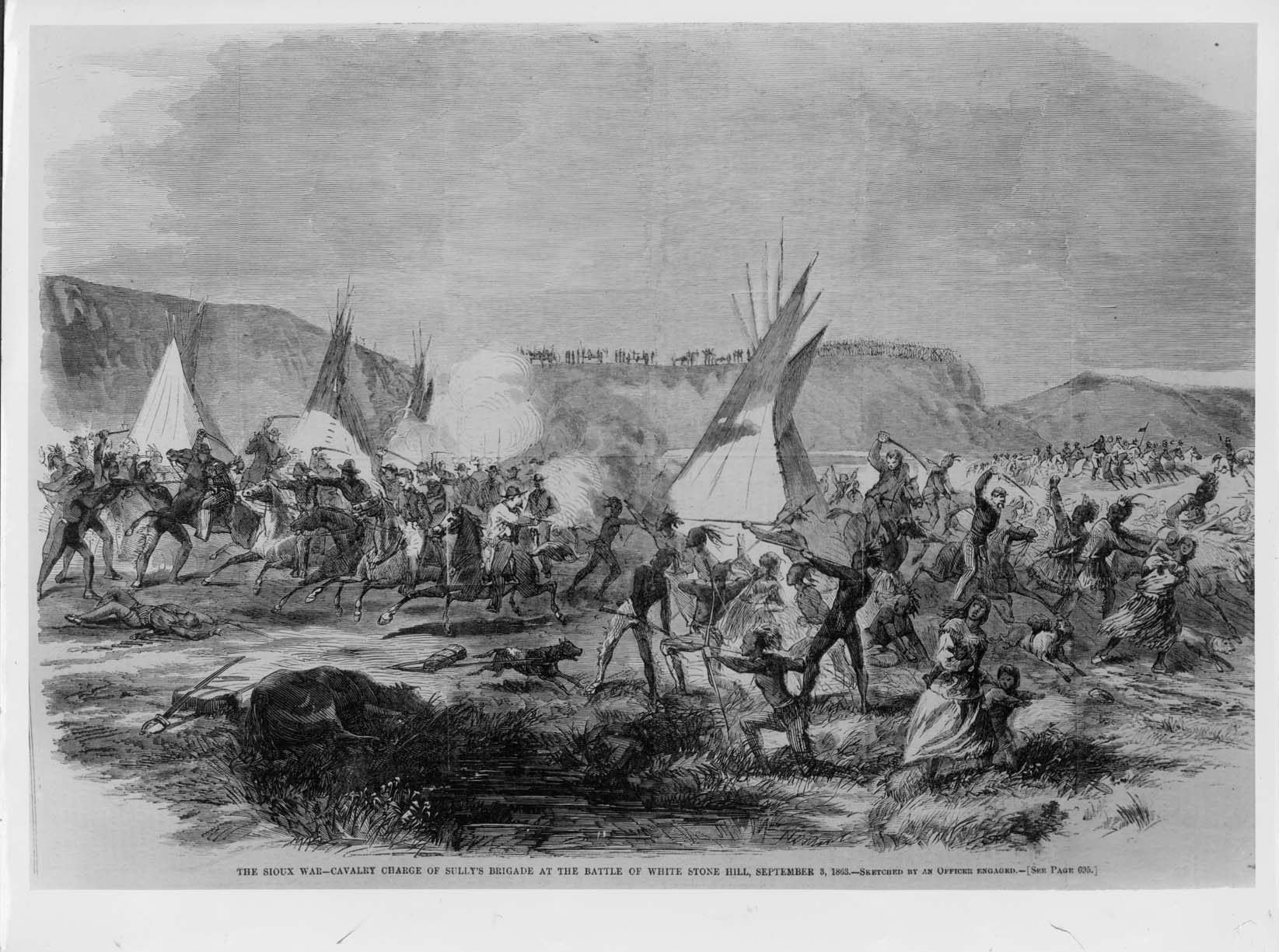

James M. Thomson Thomson, a private of Company F 6th Iowa Cavalry, kept a diary of his experiences in what he identified as the “Three Year War with Indian in Dakota.” Most of his entries are brief one or two line notes in pencil. His entries concerning the Battle of Whitestone Hill included a great deal of detail taking up five pages of his pocket-sized diary.

http://www.digitalhorizonsonline.org/digital/collection/uw-ndshs/id/3140 September the 3 [18]63 We marched 20 miles to Camp no 32 Still the 3 63 We marched about 40 miles until 3 o’clock P M when we discovered a camp of indians when we was ordered to dismount and examine our arms which was soon done and we was mounted again soon and ordered to aproach the camp which was soon exacuted and when come near hand we seen there was more Indians than we could easy handle so we dispatched to the main body of the brigad which was 10 miles distant all this time the Indians was busy packing up and getting ready to leave[.] in about 2 hours we discovered the reinforcements coming double quick and we was then ordered to pursue the Indians which was about quarter of a mile distant retreating as fast as they can[.] but we soon headed them and turned them back to the reinforcments and got them [corralled] then and we marched up to them and fired on them but they soon returned the complemint and stampeded our horses and killed 3 of our men and wounded 6 names as follows. A Baldwin and it was so dark that we could not see and we picked up the wounded and formed a hollow square and laid on our arms all night[.] at day light the next morning we heard that all the forces had retreated a mile and a half so we got the dead [men’s] weapons and [carried] the wounded to camp so there was skirmishing for 2 days and 2 men killed and one of our men wounded in the head with an arrow[.] the total amount killed is 15 men and 20 wounded and 150 indians killed and about 100 [ponies] killed and 200 captured and 150 prisoners taken[.] This is called the battle of whiteStone hill. SHSND Mss 21020 |

| Source L |

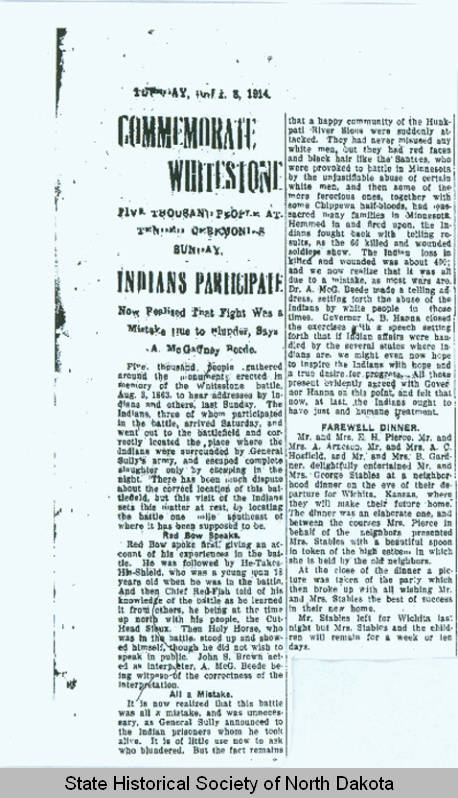

Bismarck Tribune

In September 1914, fifty-one years after the Battle of Whitestone Hill, the state commemorated its bloodiest battle with a gathering at the memorial. The newspaper account states what the official reports and earlier histories failed to note – that the battle was launched against Indians who had nothing to do with the Dakota War of 1862 and who were not preparing for war at all. Below is the newspaper account printed in the Bismarck Tribune on 9 September 1914. http://www.digitalhorizonsonline.org/digital/collection/uw-ndshs/id/3131 Commemorate Whitestone Five Thousand People Attend Ceremony Sunday Indians Participate Now Realized That Fight Was a Mistake Due to Slander, Says A. McGaffey Beede Five thousand people gathered around the monument erected in memory of the Whitestone battle, August [sic] 3, 1863, to hear addresses by Indians and others last Sunday. The Indians, three of whom participated in the battle, arrived Saturday and went out to the battlefield and correctly located the place where the Indians were surrounded by General Sully’s army, and escaped complete slaughter only by escaping in the night. There has been much dispute about the correct location of this battlefield, but this visit of the Indians sets the matter at rest, by locating the battle one mile southeast of where it has been supposed to be.  |

Frontier Scout

During the Civil War (1861–1865), General Alfred Sully led troops into northern Dakota Territory in pursuit of Dakota Indians (Oceti Sakowin) who had rebelled against their agency and nearby farmers in southern Minnesota during the US-Dakota War of 1862. Sully needed accommodations and a base of operations in Dakota Territory and for a short time housed his troops at the former American Fur Company post, Fort Union. In the summer of 1864, his troops built Fort Rice on the banks of the Missouri River about 30 miles south of present-day Mandan, North Dakota.

Shortly after Fort Rice was constructed, six companies of new recruits arrived. These were members of the 1st U.S. Volunteers (1st U.S.V.). The 1st U.S.V. comprised former Confederate soldiers recruited from the Union military prison at Point Lookout, Virginia in 1864 to serve in the Union Army. Commonly called “galvanized Yankees” after the process to coat metal with zinc to protect it from rusting where the underlying metal is unchanged. This was a derogatory way of describing soldiers who change sides during war. The use of former prisoners of war as Union soldiers was not a new idea, but it was controversial. Though members of the 1st U.S.V. briefly engaged in Civil War military action at Elizabeth City, North Carolina, General Grant feared that if they were captured by Confederate troops they would be executed as deserters. Therefore, the regiment was sent to New York City where the men boarded trains for Chicago. At Chicago, 6 companies (600 men with laundresses and officers) were sent to St. Louis to board the steamer Effie Deans to steam upriver to Fort Rice. The river was low that year and the boat could not run the entire distance, so the soldiers had to march the last 270 miles of the trip. Without wagons to carry supplies or tents for shelter, the march constituted great hardship. They reached Fort Rice on October 17, 1864. The galvanized Yankees of the 1st U.S. Volunteers were mustered out of service on November 27, 1865. Those who returned to the South met a cool welcome because of their service with the Union Army and few found adequate employment. Some returned to the West or re-enlisted in the Army.

To provide some entertainment and to relieve to some extent their feeling of remoteness from the states, the men in Sully’s command published a newspaper titled, Frontier Scout. The first four issues of the newspaper were published while the troops occupied Fort Union (volume 1, number 1 has not been located). After a delay of nine months, fifteen more issues were published at Fort Rice. Publication continued until October 1865. At Fort Rice, as at Fort Union, the newspaper helped the men remain connected to events at the post, in the region, and in the states, and it eased the loneliness of what many of them considered to be “Siberian exile” (volume 1, number 15) on the northern Great Plains. Indeed, the sentimental tone of many of the articles suggests a longing for more familiar and comfortable surroundings.

As you read through the issues of the Frontier Scout, note the details about the soldiers’ health (June 22 & June 15, 1865), and an article about Indian Policy (“Indian Im-Policy,” August 10, 1865). Think about how the isolation of the post and the circumstances of the Civil War might have shaped the soldiers’ way of thinking about the Native Americans they encountered on the northern Great Plains.

| Source P |

Volume 1/Issue 2, July 14, 1864 to Volume 1/Issue 14, October 12, 1865 |

Learn more about early military activity in North Dakota by visiting the North Dakota Heritage Center & State Museum, the numerous state historic sites including military forts, battlefields, and the Sibley and Sully expeditions of 1863, and the Civil War Era in North Dakota curriculum.