The second supporting question, “How have extreme weather events affected how North Dakotans live their lives?” helps students use sources to unwrap the context of the time and topic being examined. The climate of the Great Plains is semi-arid. That means that the precipitation varies greatly between dry (arid) and wet, and various degrees in between. Most rain tends to fall during the early growing season which is beneficial to crops. However, rainfall is characteristically unreliable. Winter snows melt into the ground forming an important source of subsoil moisture for crops and providing water to re-charge aquifers (underground pools of water). Snow cover also helps to keep the ground from freezing to a great depth which allows farmers to get crops seeded in April and protects the roots of trees, shrubs, and perennial plants. Because of these substantial swings between wet and dry, the northern Great Plains are subject to several extreme weather events including droughts, fires, floods, blizzards, and tornadoes.

The grasslands have few obstacles to slow the wind. Though wind blows year-round on the Plains, winter winds bring the most severe weather conditions when combined with snow. Wind drives snow into deep drifts in coulees and alongside, downwind of, shelterbelts. Anything that will break the power of the wind will also form a drift. Even houses and barns will form a windbreak, causing drifts to form downwind of houses. This means that if the wind blows from the north, drifts form on the south side of the building. North Dakota’s location on the northern Great Plains also means that bone-numbing cold can descend from the arctic, sometimes bringing large quantities of snow with it. The National Weather Service defines a blizzard as a winter storm with 4 criteria: winds of at least 35 miles per hour (mph); snow blowing across the ground or falling from the sky; visibility of ¼ mile or less; lasting at least 3 hours. Temperature is not a criterion for a blizzard, but temperatures generally fall below freezing. Often, the clear skies which follow a blizzard mean below zero temperatures.

Though flooding can occur almost any time of year, typically North Dakota’s most devastating floods occur in late March or early April. Severe floods generally follow winters of heavy snows and unusual cold. Though all of North Dakota’s rivers and creeks can flood, the Red River of the North which forms the eastern boundary of the state is most prone to recurrent floods. There are two primary reasons for this. First, the elevation of the ground is low, and the topography is level. Second, the river drains north, and the water is flowing into areas that may not have thawed yet, creating a natural damming effect with the remaining snow and ice. The Missouri was dammed in the 1950s which controls most of the severe flooding on that river, but the Red continues to flood regularly causing damage to urban property and to farms in the broad flat valley of the Red. Complete the following task using the sources provided to build a context of the time period and topic being examined.

Formative Performance Task 2

Study the Featured Sources below. What do they tell us about severe weather events experienced in North Dakota? Select a severe weather event, such as floods, blizzards, fires, tornadoes, or droughts, and create a poster about how it has impacted the lives of people living in North Dakota, the state’s economy; and key industries.

Featured Sources 2

The sources featured below are primary sources. They are the raw materials of history—original documents, personal records, photographs, maps, and other materials. Primary sources are the first evidence of what happened, what was thought, and what was said by people living through a moment in time. These sources are the evidence by which historians and other researchers build and defend their historical arguments, or thesis statements. When using primary sources in your lessons, invite students to use all their senses to observe, describe, and analyze the materials. What can they see, hear, feel, smell, and even taste? Draw on students’ knowledge to classify the sources into groups, to make connections between what they observe and what they already know, and to help them make logical claims about the materials that can be supported by evidence. Further research of materials and sources can either prove or disprove the students’ argument.

Examine Featured Sources A-V. In a group or as a class, answer the following questions: What type of sources are these (letters, photos, maps, diaries, etc.)? What kind of information do they contain? Who created them? Who was the intended audience? Why were they created? When were they created? How do we know? What else can you find?

Blizzards

North Dakotans are used to winter blizzards though the weather service records indicate that typically there are only 3 or 4 severe blizzards each decade. Considering the irregular precipitation of the northern Great Plains, residents have come to expect blizzards at any time between late October and late April. There are many memorable blizzards. The January 12, 1888 blizzard destroyed what was left of the open range cattle industry in North Dakota and killed 112 people. The blizzard of March 15, 1941 came through quickly and with little warning. Thirty-nine people died, most of them trapped in their cars.

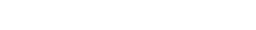

One of North Dakota’s tragic blizzard stories is about a young girl named Hazel Miner who died in a blizzard on March 16, 1920. Hazel, the 16-year-old daughter of William and Blanche Miner, had gone to school with her younger brother Emmet (11) and sister, Myrdith (8) on Monday March 15. They drove a horse-drawn sleigh from their farmhouse 2 ½ miles north of the rural school. In the afternoon, a blizzard came up and the children’s father rode his horse to the school to bring the children home. Mr. Miner hitched the sleigh horse and then went to get his saddle horse from the school barn. In the meantime, the sleigh horse started out of the school yard and took what the children thought was the road home. Mr. Miner could not find them in the blizzard, and they could not hear him call above the wind. Instead of heading north to their home, they headed east. Mr. Miner went home and with his wife went back out to look for the children. The sleigh crossed the road and came to the gate of a farmyard which they could not enter because of a big drift. They drove a few yards further, and then the sleigh tipped over into a ravine. Though a haystack and a farmhouse were nearby, they could not see their way to shelter. After the sleigh tipped, Hazel tried to keep the wind off the children by holding the sleigh blankets for shelter, but the wind kept blowing the blankets down. Finally, she pulled the blankets over the smaller children and lay down on top of the blanket to keep it in place and to keep the younger children warm. Hazel talked to Emmet and Myrdith through the night and told them to keep moving their feet. She punched them to keep them awake and kicked off the snow that was seeping in under the blankets. Sometime during the night, Hazel died. When a search party found the sleigh the next morning, Emmet and Myrdith were still alive. Hazel’s love, clear thinking, and brave actions saved her brother’s and sister’s lives. After her death, Hazel became a national hero. Articles were published in newspapers and magazines, and songs were written about her. Hazel Miner’s courage was honored with a statue that stands in front of the Oliver County courthouse. The statue was commissioned by former Governor L. B. Hanna in 1936.

The blizzard of March 2, 3, and 4, 1966 may have been the worst recorded storm to hit North Dakota because of its long stay across the state, snowfall accumulation, and high wind speeds. This blizzard came with plenty of warning from the weather service, but no one had experienced a blizzard of this power and duration. It began about noon on Wednesday March 2. The State Highway Department requested travelers to stay off the highways, and by Thursday, cities were asking businesses to close and for residents to stay off city streets. Visibility in the open country, and even in farmyards, was reduced to zero for 11 hours, and zero to 1/8 mile for another 19 hours. By Friday night, the winds had reached 70 mph with gusts in some locations to 100 mph. The wind blew the snow about leaving parts of some highways clear, but other stretches had drifts that were 20 to 30 feet high and hundreds of yards long. The actual snowfall varied but reached from 20 to 35 inches in places. During the storm, Highway Department volunteers attempted to rescue travelers stuck in their cars. They managed to get to a few of them, but many remained trapped until Friday evening when the storm finally let up. Only the northwestern corner of the state was spared the destructive power of this storm.

Despite the warnings, some travelers were caught in the storm. Two of these were couples trying to get to the Dickinson hospital in time for the birth of their child. One child was born in a farmhouse before the couple was able to get to Dickinson; the other was born after the couple’s car got stuck twice in town, and the mother and father had to walk the last few yards to the hospital. Three trains, one carrying 500 passengers, were stalled by deep drifts near New Salem. All three trains eventually had to be dug out of the drifts by men with shovels because the drifts were too deep for snowplows mounted on work engines. Five North Dakotans died in the storm (18 died throughout the storm’s path in three states). Three of the victims were men who died of heart attacks while trying to shovel or walk in the storm. Two victims were young girls who had left their farm homes to tend to livestock in the barn but lost their direction in the blizzard’s swirling snow and wind and walked away from the house and barn into the pasture.

The economic impact of the storm was enormous. Official records show that 74,500 head of cattle, 54,000 sheep, 2,400 hogs, and numerous other livestock perished in the storm. Some of these were in open fields where snow blinded them, causing them to drift into fences where they died; others died in barns that were covered with snow drifts and sealed so tightly that the livestock suffocated; some died in barns that collapsed under the weight of the snow. City businesses shut down and many buildings were damaged by heavy snow. Blizzards cost money. Farmers, cities, individuals, and state agencies pay extraordinary costs to repair the damage from storms. State Highway Department officials complained that they did not have enough trucks and bulldozers to move the snow after the storm stopped, because of the great expense of buying and maintaining such equipment. The livestock killed in the blizzard of 1966 was valued at $12,000,000. The Red River flood that followed this blizzard cost $7,900,000.

During blizzards, as schools close to the delight of children, businesses shut down and the residents of North Dakota take a small, at-home vacation from their daily routines. However, blizzards also take time and effort as people try to live through and recover from them. In the Blizzard of 1966 snow removal took the lives of three men; men working for the Highway Department risked their lives to rescue stranded travelers on the highways. Two weeks after the blizzard, Ida Kellogg (Featured Source B) was still exhausted, still drained by worry, and still fearful that she and her boys might have died in the storm while trying to save their livestock. Snow is part of winter routine on the northern Great Plains. Rather than drive people away or prevent the development of towns and cities, people learn to adapt to the usual cold and snow of winter and to accept unusual storms such as that of March 1966 as part of life in the semi-arid north.

Flooding

Hydrologists and weather forecasters look at 5 conditions that often lead to severe spring flooding:

- An unusually wet fall preceding winter. This leaves the ground saturated with little room for additional moisture to be absorbed.

- An unusually cold winter. Deeper frost is slow to thaw and prevents the ground from absorbing moisture.

- An unusually heavy accumulation of snow during the winter.

- A late, cool spring, with a sudden warming trend. A late spring allows for further accumulation of snowfall and cool temperatures prevent periodic thaws. Sudden warming means a rapid melt of the winter’s snow.

- Heavy rain throughout the river’s drainage area during the thaw. Warm rains not only add to the moisture levels, but also melt snow rapidly.

In 1920, Representative Douglas M. Baer of North Dakota brought the Red River of the North to the attention of Congress. In his speech, he requested $25,000,000 in funding for the Army Corps of Engineers to develop a plan for flood mitigation on the Red. He argued that the Red had routinely destroyed the Valley’s wheat crop. Along with ND State Drainage Engineer Herbert A. Hard, Baer pointed out that flooding in 1915 had resulted in $15,000,000 in agricultural losses; the two floods of 1916 had cost $20,000,000; and the 1917 flood had cost $15,000,000. Baer’s proposal for controlling floods on the Red included ditches, channel improvement, and impounding dams on the Red’s tributaries.

Early in April 1950, the Red was again rising to flood stage. The flooding began to reach Pembina on April 17. The temperatures had reached 50 degrees earlier in the week. By April 20, floodwaters covered the railroad tracks and undercut the railroad ties. The main road, Highway 81, was under water in several places. The water kept rising and reached a crest of 51 feet 8 inches on April 30, nearly 10 feet above flood stage and exceeding by one foot the previous flood record set in 1897. Eighty homes (283 people) were evacuated; some houses collapsed under the pressure of water against the foundation. In addition, the Pembina city well cracked leaving the water supply contaminated. In May, heavy rains again caused the river to rise. Army duck boats arrived to remove residents and their belongings. Some buildings were protected by sandbags, but the locker plant, which had remained dry during the initial flooding, began to take on water despite its sandbag dike and plastic lined walls. On May 13, just before the flood’s crest, Red Horse Johnson, owner of the Pembina Locker Plant, had to ship the contents of 400 frozen food lockers to Fargo until the waters receded. A locker plant was a business where people could rent cold storage for food when home refrigeration was less common. The Coast Guard transported the food by boat to the Great Northern Railway which took the goods to Fargo. The second crest exceeded the first crest reaching 53.125 feet on May 13. As the waters slowly receded, the residents of Pembina held a parade of Army and Coast Guard boats and small motorboats led by a man walking through the water in his Shriner’s garb. American flags brightened the parade, which was held on Armed Forces Day, May 20.

The flood of 1950 was one of the worst on record in terms of record crests and water quantity in the stream. The Red was above flood stage at Grand Forks from April 9 to June 4. The damage amounted to nearly $31,000,000. Pembina County recorded the highest property damage and the most individual families experiencing loss. Seven people were injured in Pembina County, and one died in Grand Forks County. Once again, North Dakotans adapted to the periodic trials the climate presents. The parade at Pembina suggests a strong spirit of cooperation among residents to cope with the inevitable floods of the great river.

During the winter of 1996-1997, eastern North Dakota experienced heavy snowfalls and deep cold. Early in April, the eighth blizzard of the season, nicknamed Hannah by the Grand Forks Herald, struck, paralyzing the state, and bringing deep cold once again to the Red River Valley. On April 18, 1997, the Red, reaching a crest of 54.35 feet, breached the dikes at Grand Forks flooding the city, destroying the water plant, and starting an electrical fire that gutted the downtown business district.

Over the years some minor improvements have been made, including the building of Baldhill Dam on the Sheyenne River in 1950 to help control floods on one of the Red’s largest tributaries. However, despite a succession of engineers and water development councils discussing the problem for decades, the Red still floods frequently. Flooding along the Red is often severe because the valley is predominately level, so farmland, towns, and rural homes are all at risk. The water also takes longer to drain away as the river flows north, where conditions may be colder, and the river still remains frozen farther north.

| Source A |

|

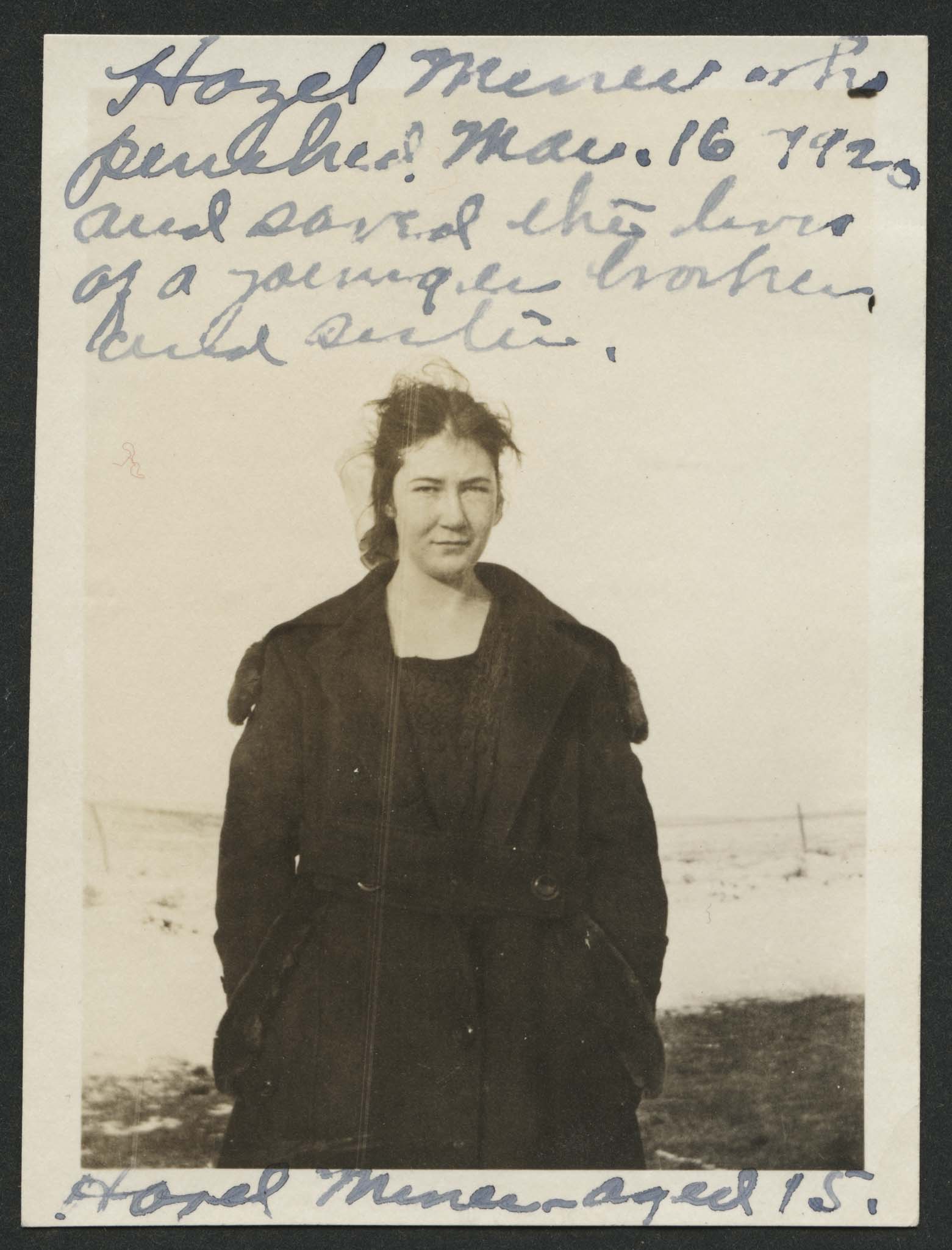

| Source B |

Shortly after the blizzard of March 2, 3 and 4, 1966, Ida Kellogg of Monango (Dickey County) wrote to a friend in Minneapolis describing the three-day storm and how her family survived it. SHSND Mss 20272 http://www.digitalhorizonsonline.org/digital/collection/uw-ndshs/id/3753 |

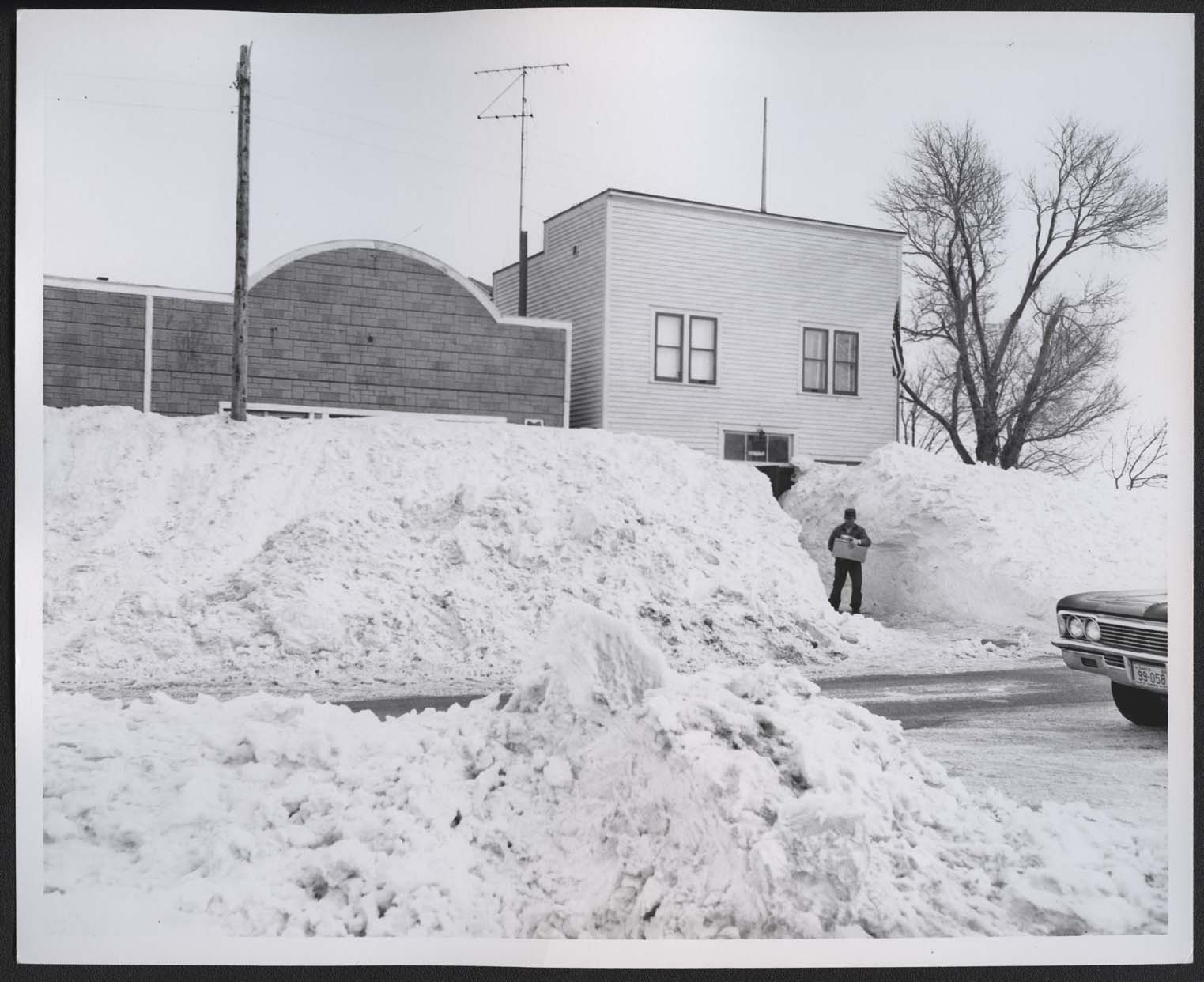

| Source C |

Hague’s main street shows the hardship that the blizzard visited on towns. Snowpack caused by drifts and street clearing appear to be more than 8 feet high. Access to stores is limited. Photo dated March 9, 1966. SHSND C1473. |

| Source D |

The Blizzard of 1966 hit south central North Dakota very hard. Near Linton, this Northern Pacific Railroad engine was severely damaged by snow. This photograph was taken three days after the blizzard ended. SHSND C1469. |

| Source E |

Sebastian Krumm’s house near Hague had snow to the rooftop. Krumm had to shovel snow from the roof into the attic to get out of the house. The roof began to crack under the weight of the snow so Krumm used household furniture to brace the roof against the weight of the snow. The car in front of the house where the men (including Krumm and National Guard troops) are shoveling was crushed by the weight of the snow. Only Krumm’s dog enjoyed the results of the storm; he ran up the drifts, over the roof, and down the other side. Photo dated March 9, 1966. SHSND C1475. |

| Source F |

Even snow removal equipment became stuck in the snowdrifts. Here National Guard Sergeant Adams and his crew use shovels to free a bulldozer on March 8, 1966. SHSND C1472. |

| Source G |

Nearly 140,000 head of livestock died in the storm. Some died in barns, others were in pastures as this animal was. SHSND C1477. |

| Source H |

This view of the bridge over the Red River at Pembina indicates how high the water got in May 1950. SHSND 2009-P-014-39. |

| Source I |

Red Horse Johnson’s Locker plant was located in downtown Pembina. It is the white building in the center of this image with an open door and octagonal window. SHSND 2009-P-014-01. |

| Source J |

As the flood waters rose, Johnson wrapped the base of the locker plant with black plastic and built a sandbag wall around the building. SHSND 2009-P-014-45. |

| Source K |

Johnson stands in front of the locker plant. The water has risen a little higher. SHSND 2009-P-014-46. |

| Source L |

Red Horse Johnson looks out from the boarded-up door of the locker plant. He soon had to take all the frozen food from 400 lockers and transfer it by boat and then train to a locker plant in Fargo. SHSND 2009-P-014-48. |

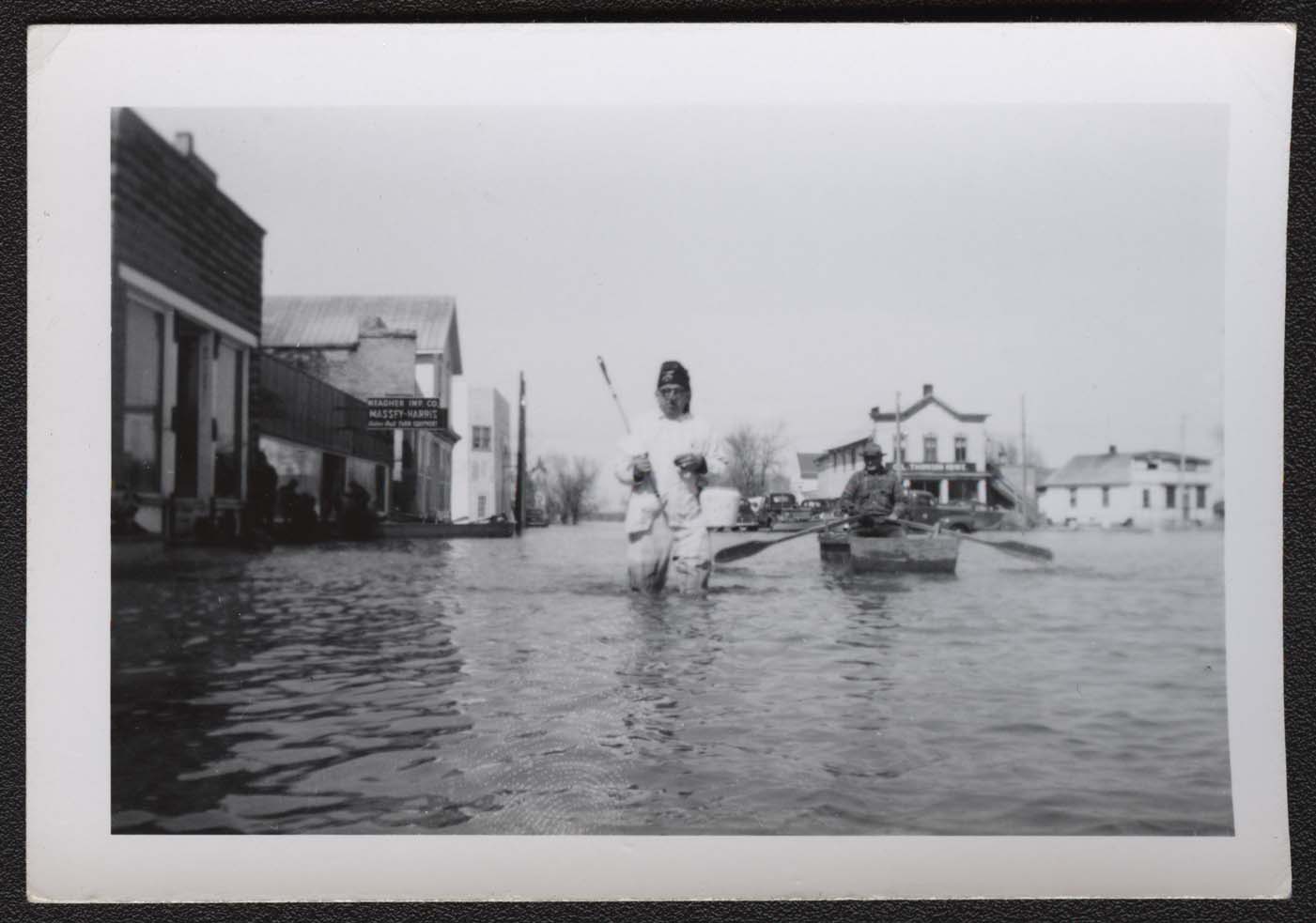

| Source M |

In honor of Armed Forces Day, May 20, 1950, residents of Pembina held a water parade led by a Shriner in dress uniform. SHSND 2009-P-014-29. |

| Source N |

These parade participants wore fancy hats and decorated their rowboat with a cardboard cutout of a hula girl. SHSND 2009-P-014-49. |

| Source O |

Parade watchers had a good seat on top of the sandbag dikes. The walk to the parade route required hip waders. SHSND 2009-P-014-51. |

| Source P |

The flood waters remained high for several weeks. Mr. and Mrs. Bud Feldman carry on with ordinary life as they hang their laundry out to dry while standing in a boat. SHSND 2009-P-014-20. |

| Source Q |

1997 Flood The following photographs were taken by workers for the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). FEMA (Federal Emergency Management Agency) collection. SHSND DR 1174-ND Red River Flood 1997 SA 32189.

In the spring of 1997, Grand Forks reinforced its dikes and added sandbags on top of the dikes to try to prevent flooding. The dikes gave way and the river entered city neighborhoods and downtown businesses. Grand Forks 005. |

| Source R |

The river reached the rooftops on some Grand Forks and East Grand Forks homes. IMG0066. |

| Source S |

After evacuation, rescue crews of city firefighters, police officers, and National Guard troops checked houses to be sure everyone was out and to rescue dogs and cats that had to be left behind if people were evacuated by boat. Grand Forks 015. |

| Source T |

Businesses were damaged by floodwaters. Restaurants and other businesses that sold food had to rebuild and completely disinfect or replace all of their equipment. IM0006. |

| Source U |

In order to completely dry out a house and prevent mold formation within the walls, homeowners had to remove and dispose of dry wall, paneling, cupboards, and woodwork. Grand Forks 025. |

| Source V |

Some neighborhoods were filled with things that floated in on the river, but after the waters receded, every home had to throw out anything that was destroyed by the flood. Some things were contaminated by dirty floodwater and could not be made safe by washing. Grand Forks 0003. |