The third supporting question, “What were the arguments for and against women’s suffrage?” helps students use primary sources to unwrap the context of the time and topic being examined.

Complete the following task using the sources provided to build a context of the time period and topic being examined.

Formative Performance Task 3

Research woman suffrage in other states in 1900. Using a blank map of the US, create a key that indicates which states had granted women either partial or full suffrage.

- Do you see any patterns?

- Was North Dakota in line with what other states were doing?

How do we know? What else can you find?

Study the text below and featured sources A-B.

- Which members of the convention favor women’s suffrage, and which do not?

- Which argument seems stronger? Why?

- If suffrage is offered by the legislature, rather than as a guaranteed right in the state constitution, is suffrage at risk of being revoked later?

- Why didn’t the members of the constitutional convention who opposed suffrage for women offer amendments? What was their strategy?

- Does this strategy appear in any other amendment deliberations? How did they turn out? Why?

Featured Sources 3

The Constitutional Convention met on July 4, 1889 to prepare the document that would provide the foundation for governance in the new state of North Dakota. Seventy-five members of the 1889 constitutional convention met in Bismarck from July 4 to August 17. The members of the convention were mostly Republicans and just nineteen Democrats. Fifty-two of the members were born in the United States. F. B. Fancher was elected President of the convention. Fancher later served as governor of North Dakota (1899 -1901). P. 276. The convention was presented a constitution that had been drawn up by Professor James Thayer of Harvard Law School, written at the request of Henry Villard, chairman of the board of the Northern Pacific Railroad. Few questioned that the railroad, which opposed both prohibition and woman suffrage, would have a strong influence in state government. Thayer’s constitution was amended many times before the convention closed on August 17. Among the issues before the convention were the placement of state schools and institutions, child labor, and suffrage for immigrants.

Woman suffrage was another debate that not only had place in this convention, but in the United States as well. By this time, the territory of Wyoming had granted women the right to vote and hold office. Other states and territories had offered women limited suffrage. Women had voted on school issues in Dakota Territory since 1883. The debates concerning full woman suffrage as well as the right of women to hold office tells us a lot about what people at the time were thinking of political and social issues. During the Constitutional Convention, the leadership of woman suffrage was in the hands of Linda Warfel Slaughter of Bismarck. It is not likely that there were any other members of the National Woman Suffrage Association or their rivals, the American Woman Suffrage Association in North Dakota (AWSA). The members of the convention were correct in assuming that there was no widespread “agitation” for suffrage at that time.

On July 8, Henry B. Blackwell addressed the convention. Blackwell was a Boston businessman and supporter of woman’s rights. His wife, Lucy Stone had scandalized the nation when she refused to take Blackwell as her last name when she married. Blackwell and Stone devoted their lives to abolition and rights for women and were founders of the AWSA. The fight for woman suffrage was progressing in the United States and national organizations such as AWSA focused on new states as important battlegrounds for woman suffrage. At the conclusion of his lengthy address to the convention, Blackwell said:

“Give us woman suffrage in the body of the Constitution or a clause empowering the legislature to take that step when the judgement of the public will sustain it.... I trust you will give Woman Suffrage candid and earnest and enthusiastic support.” (p. 41)

Members of the convention agreed that woman suffrage should not be included in the constitution but should be a matter for the legislature to decide. Supporters of woman suffrage were content to let the legislature decide the matter, and opponents asked to have any bill for woman suffrage that passed through the legislature submitted to a vote of the people for ratification. Woman suffrage was often compared to the prohibition clause of the constitution which would be submitted to the people for a vote. Samuel H. Moer, a Republican lawyer from La Moure, suggested that woman suffrage should be handled in a similar manner, and that any bill passed by the legislature for the extension of suffrage should be submitted to the people for a vote.

John W. Scott, a Republican lawyer from Valley City, agreed the question of woman suffrage could be brought to the legislature at any time, and should be ratified by the people. He said:

“I believe that this is a matter of great importance – that the question as to whether or not there shall be woman suffrage is of equally as much importance as anything that will come before the people of this State. I regard it as being a matter of far great importance than prohibition, which we will submit to the people for their acceptance or not…the question is not one that has been sufficiently thought of by the public, or demanded sufficiently by the public for us to take this step at this time. There has been no serious discussion of the question – it has only been agitated by a few, and so far as I am personally concerned I should be willing to leave it to the women of the State themselves, provided they would get out to vote – to leave it to them to say whether or not there should be woman suffrage.” (p. 277)

Robert Pollock, a lawyer from Cass County, noted that the proposition to have suffrage brought before the legislature, rather than including it in the constitution, was favored by the franchise committee. However, Pollock did not favor bringing the vote to the people because the voters who would vote on the issue would not include women. (p. 279)

Lorenzo Bartlett, a farmer from Ellendale, and one of the oldest members of the convention (born in 1829) brought social issues to bear on the debate.

“...in all my travels wherever I have been, if the question was put to a...crowd of ladies as to whether or not they wanted to vote, they have always said no. The answer to that made by the advocates of the theory [of woman suffrage] is that the ladies are enslaved. They have lived so many years and they don’t know what they do want, simply because they are enslaved. I ask every gentleman here, and every woman here, if by their experience there is true happiness in those families where they are calling for female suffrage. What is your life’s experience? Echo answers every time, that where two parties fight with one another in the same family, that happiness does not follow....Three years ago in St. Paul, the women of America who believed in woman suffrage met in convention and they had a lady reporter that reported that convention. There were there 500 of the most talented women in America. I don’t deny their talent and ability, but I do deny most emphatically that the principle they advocated would bring any happiness into the world. The lady who reported that meeting wrote me and, said she: ‘In their countenances you could see intelligence, but you could also see sorrow and woe. They are anything but happy people, and their countenances show that their homes are not happy.’ Show me one single individual family that is in favor of woman suffrage - I mean those who make a business of it – and how are their children? Do they raise a family equal to those who don’t believe in it? No. That is life’s experience of those who have noticed these things....[A]nd unfortunately it will come in a great many cases, that very moment if the man is a republican the woman will become a democrat, or if the man is a democrat the woman will become a republican. Anything that brings discord and sorrow into the family is not for the best interests of the people.” (p. 280)

Mr. Moer’s amendment – to place the question of woman suffrage to the vote of the people passed 35 to 25.

Ezra Turner (a Republican farmer from Bottineau) offered another amendment that would allow legislature to decide on woman suffrage but deny women the right to hold elective office. Turner argued that if women were not happy when they asked for the franchise, it might be because they were “enslaved” and

“persons who are enslaved are not usually very happy.... Is there any reason why these women should be happy when they are deprived of their just rights and privileges, and are compelled to obey laws in which they have no right to cast a vote or say whether these laws shall prevail? Is it not reasonable that these women should be unhappy when they see their sons dragged from their protection, under the influence of those who are following what they hold to be an unlawful business, dealing out that which destroys the manhood of their sons, and which curses and blights…[At this point Turner was interrupted and reminded to stick to the subject]. Holding these views as I do, I am anxious that this amendment should pass, so that the right of the franchise may by the Legislature be extended to women, but not the right to hold office unless the voice of the people so declare.” (p. 283-284)

Turner’s motion lost.

On the forty-third day of the convention the question of school suffrage for women came forth for debate. Women had had the right to vote on all matters relating to school issues since 1883 under territorial law and a woman, Linda Warfel Slaughter, had held the elective office of Burleigh County Superintendent of Schools as early as 1878. The new constitution had a clause to continue the right of school suffrage for women. However, the details were subject to debate. Lorenzo Bartlett offered an amendment to make the constitution limit school suffrage to “any single woman” instead of “any woman” (p. 573) Rueben Stevens (R., Lisbon) opposed Bartlett’s motion stating:

“I hope this Convention will not offer a premium on old maids.... I haven’t any use for them.” (p. 573-4)

The limited vote suggested some problems. Mr. Moer asked if the amendment meant that women could vote on school issues at the state level, such as state superintendent of schools, or would be limited to local school issues. (p. 574) Eugene Rolfe (Republican from Minnewaukan) asked if women would have to show their ballots to prove that they had voted only on school matters and not on other issues and offices before the voters. If so, their right to a secret ballot would be impaired. (p. 574) William Rowe (Republican from Monango) explained that:

“There can be a separate ballot box for the women, and it will not be necessary for them to exhibit their ballots.”. 574.

Reuben Stevens (Republican of Lisbon) said that it would be:

“absurd to say that women are entitled to vote for school directors and not for school superintendent and other school officers. If they are entitled to vote for school director as they are now allowed to do under our territorial laws, it is on the principle that they are entitled to have something to say in the government of our common schools.... Whatever little education I have I owe to my mother, and not to my father. I say the women of this country are interested more in the subject of education than the men, and I say they should be entitled to vote on this question, and if they vote on any branch of it, they should vote on all of it.” (p. 575)

The measure passed. Women were to have separate ballots and the right to vote on state superintendent of schools. While North Dakota gave women the right to vote on school issues, the legislature refused to grant an extension of the franchise until 1917 (under the Non-partisan League). This advance was still not complete, and women did not have full suffrage until the 19th amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1920.

Tuttle, R.M. Official Report of the Proceedings and Debates of the First Constitutional Convention of North Dakota, Assembled in the City of Bismarck, July 4th to August 17th, 1889. Bismarck: Tribune, State Printers and Binders, 1889. Available online.

| Source A |

First All-Women Jury in North Dakota: In 1923, three years after full suffrage was granted to all women citizens of the United States, Burleigh County impaneled an all-woman jury. North Dakota law included women voters in county jury pools. Women voters could be excluded from jury duty only if they applied in writing to be excused. Some of the women in the photo of this rare event, were among the leading women of Bismarck and Burleigh County. The bailiff, Linnie Hedstrom, is the wife of Sheriff Albin Hedstrom and daughter of Linda Warfel Slaughter. SHSND 0091-0243.https://statemuseum.nd.gov/database/photobook/index.php?content=photobook-itemdetails&ID=PH_I_146525&CollectionNmbr=00091&PBID=84215 |

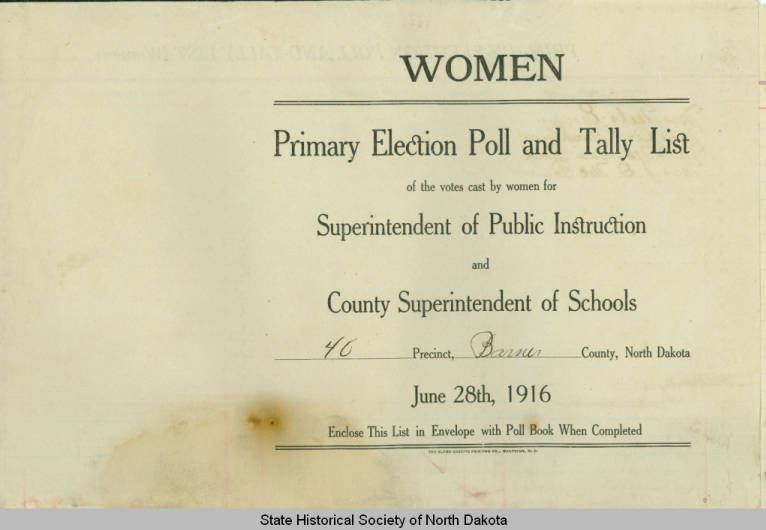

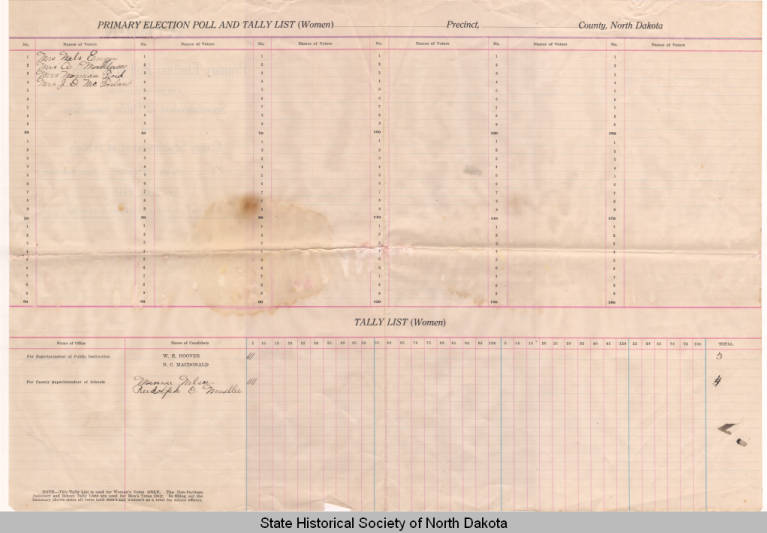

| Source B |

Women’s Suffrage Documents

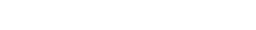

This letter, addressed to Linda Warfel Slaughter in 1887, indicates the excitement the writer felt at voting in a school election. SHSND Mss 10003.

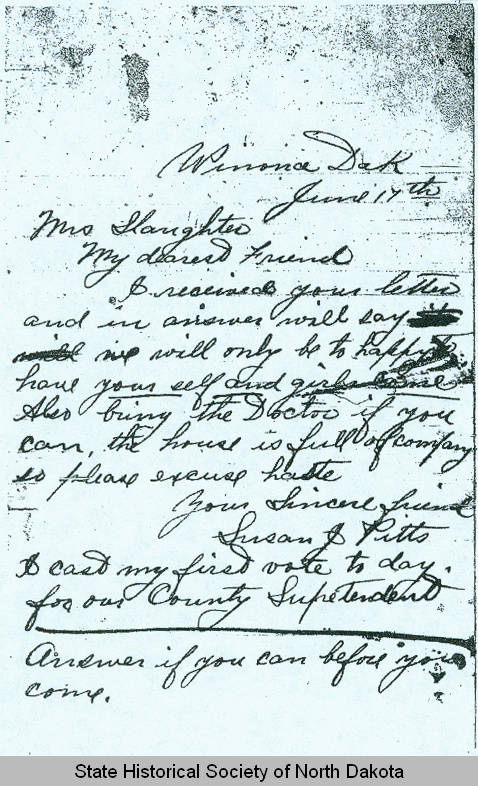

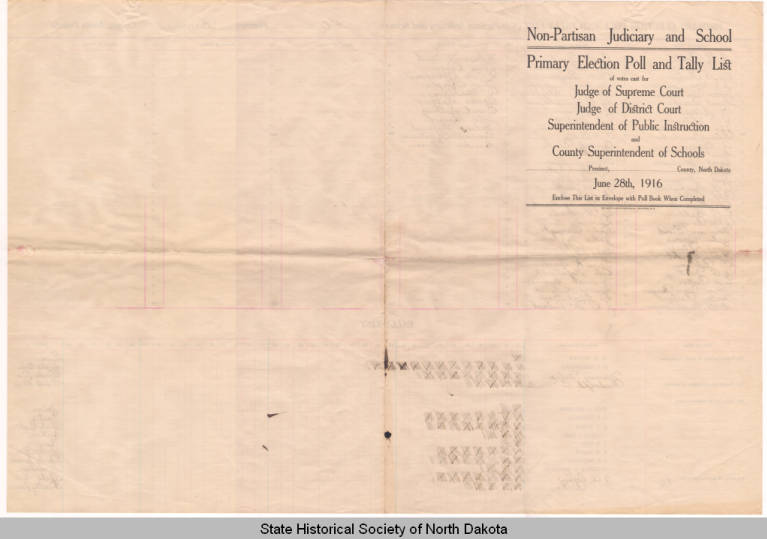

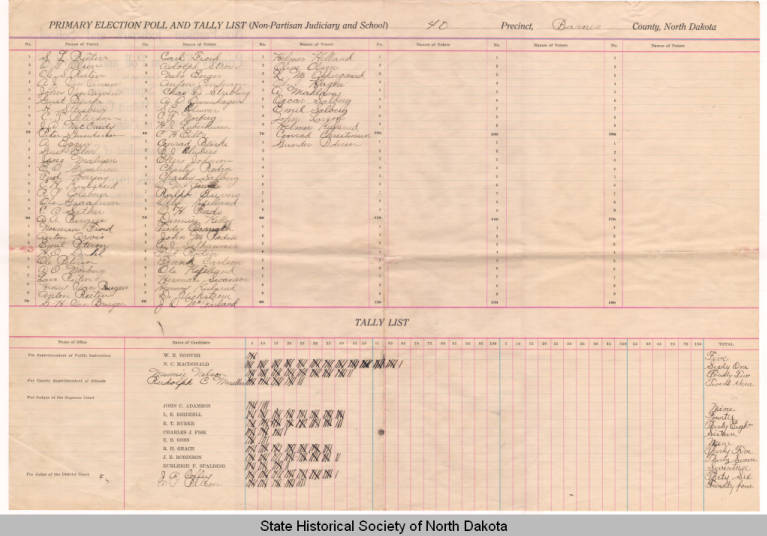

These two documents are the front and backside of ballots used by men and women, respectively, to vote in the primary election of June 1916. Note the difference in the ballots. Women could not vote for judges in 1916. How many women voted compared to the number of men? http://www.digitalhorizonsonline.org/digital/collection/uw-ndshs/id/3122 |

Learn more about women’s suffrage in North Dakota.