When cars began to appear in North Dakota, little thought was given to women’s ability or right to drive. Women were happy to have an automobile in the family and were often willing to make sacrifices to buy one. Many people, however, assumed that men would actually operate the vehicle.

Nevertheless, women did learn to drive. (See Document 12) They had to be physically strong enough to turn the crank on the front of the car to start the engine and able to change tires (flats were very common). (See Image 33.) If those minimum standards were met, women could (and did) drive as well as men. There were no age limits and no tests for drivers until the 1930s. In 1908, twelve-year-old Esther Nichol drove a car to make deliveries for her father, a butcher in Souris. Her father wanted her to deliver meat to the cook cars in the fields during wheat harvest. She drove a friction-drive Frykman car (made in Souris) that did not have a transmission and transferred energy from the engine to the wheels via a chain. (See Image 34.) Esther later remembered:

“When I was twelve I learned to drive in that high wheeler. I wasn’t strong enough to crank it, so a neighbor went with me and we made the rounds of the ‘cook cars’ at threshing time delivering fresh meat. Of course our part of North Dakota was level but when we went to Lake Metigoshe in the Turtle Mountains, many times the chain would come off and we’d have to back down and put on the chain on the back wheel somewhere!”

The car was equipped with a bright searchlight so that Esther could return home after dark. Frank Jaszkowiak built automobiles in Bismarck in as early as 1902. His wife considered automobiles useless, or so she told the city tax assessor who wanted to place a taxable value on the car as personal property. She may have considered her husband’s machine a waste of time and money, or she may have been trying to avoid a tax assessment when she told the tax assessor that her husband’s cars “were of no practical value." (See Image 35.)

A little girl was probably the first victim of an auto accident in 1901. For about 20 years after cars appeared on North Dakota’s streets, pedestrians continued to believe that their safety was the automobile driver’s concern. When 10-year-old Clara Summerhauser rode her bicycle on a Grand Forks street in 1901, she was unaware that she should have been watching for Dr. Henry Wheeler dashing about in his expensive new car. Dr. Wheeler struck the girl on her bike and she was knocked unconscious. She recovered a few days later. The slow speed of early automobiles probably saved her life. The car that struck Clara Summerhauser had been built by Dr. Wheeler himself. He had paid $1,000 ($28,011 today) for an automobile kit. He was a popular young man and drove the car around town to attract the attention of young women. For many women, riding in Dr. Wheeler’s car was a social event worthy of notice in the Grand Forks newspaper. Cars had a particularly strong impact on social relations among young people. For decades, a young man courted a girl by calling at her parents’ home. The visits were supervised and young couples were seldom alone unless the parents (especially the mother) approved. When young men began calling on women in their own cars, however, the couple might have driven to another town for a movie, a dance, or to the countryside to be alone. Girls riding in cars with their dates challenged old traditions of parents controlling their daughter’s social life – and her reputation. While changing social traditions is a very slow process, dating couples driving in cars coincided with social changes that came about because of World War I and the campaign for woman suffrage. (See Image 36.)

.jpg)

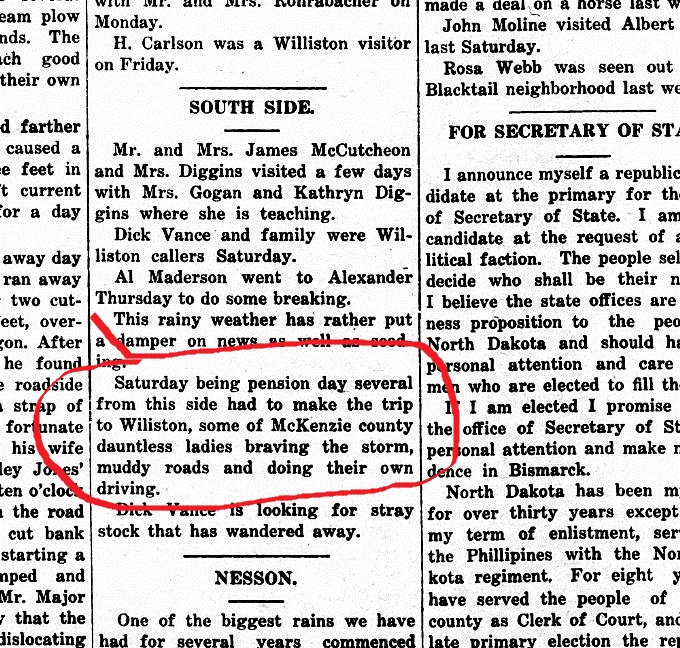

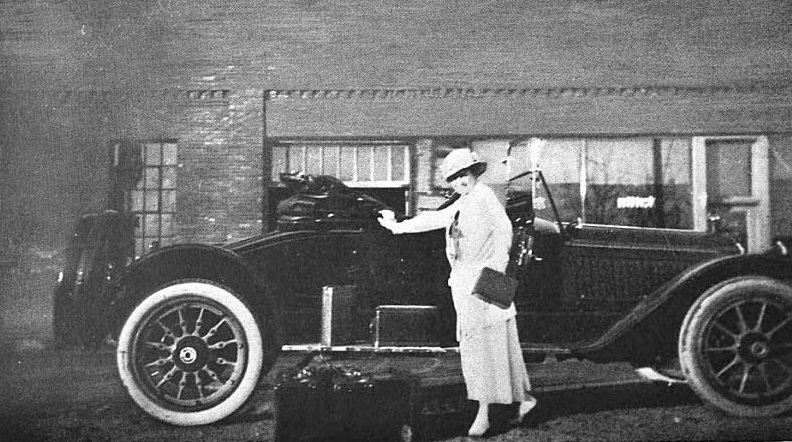

Automobile travel across the state and across the country was increasingly popular with men and women. After a trip from Bismarck to Massachusetts in 1916, Edith Wakeman Hughes wrote a book about her experiences. (See Image 37.) They met people all over the country, on country roads, and in the cities they visited. Edith was in charge of the route and the choice of hotel, while her husband was always the driver. She, perhaps unwittingly, contributed to the stereotype of women as “backseat drivers” by making it her job to keep an eye on their speed. (See Document 13.)

Why is this important? Whenever we study the past, we should ask if events or ideas of a time period affected men and women differently. In studying the early impact of cars on work and social life, we see that cars gave both women and men greater mobility and new economic opportunities. However, the social impact of cars for women was very different than for men. Today, we think nothing of women riding in or driving cars, motorcycles, race cars, tractors, and trucks. But, before 1940, women driving cars or riding in cars with men was part of the discussion about the changing place of women in American society.