All towns and cities were built around streets. When a city was originally planned (platted), streets were laid out first. In larger cities such as Fargo or Bismarck, the main streets were paved with bricks or wood blocks, but in small towns the streets were usually just packed dirt. Residents complained about streets in bad condition and poor quality paving. However, residents also complained about having to pay high taxes for road construction. City engineers, contractors, and citizens debated the proper kind of material for paving city streets. Engineers had concerns about how paving materials would hold up to North Dakota’s hot summers and cold winters.

Bismarck, Fargo, Minot, Grand Forks, Devils Lake and other cities began paving their streets around 1910. The process continued for many years. Some city streets were surfaced with gravel and clay, but main streets were usually paved with brick, or bitulithic – a substance similar to modern asphalt. (See Image 19.) Both Fargo and Minot had pre-automobile pavement of wooden blocks that had been treated with creosote. These, of course, were badly damaged when these cities’ streets flooded. Some cities issued license plates before the state did. Valley City issued license plates to 96 automobile owners in 1909. The licenses cost three dollars and were good for two years. Northwood, Bismarck, and Dickinson also issued license plates in 1910. City plates were used until the state passed a licensing law in 1911. The state highway department did not build bridges until the 1930s, but some towns constructed bridges to draw more traffic and more business to their merchants. The town of Marmarth built a bridge over the Little Missouri River for both local traffic and for travelers on the Yellowstone Highway. Medora also built a bridge over the Little Missouri River. It was paid for “by subscription” meaning that private individuals and businesses contributed to the cost of construction. Many towns saw an increase in business and population as automobiles became more popular. Cars took farm families from small market centers to larger cities to shop, to access medical care and other services, and to market their crops. Many rural families bought cars so that they could shop in larger towns. Small towns like Fillmore and Omemee lost business and population as cars swiftly carried farm families to Rugby or Bottineau to shop. (See Image 20.)

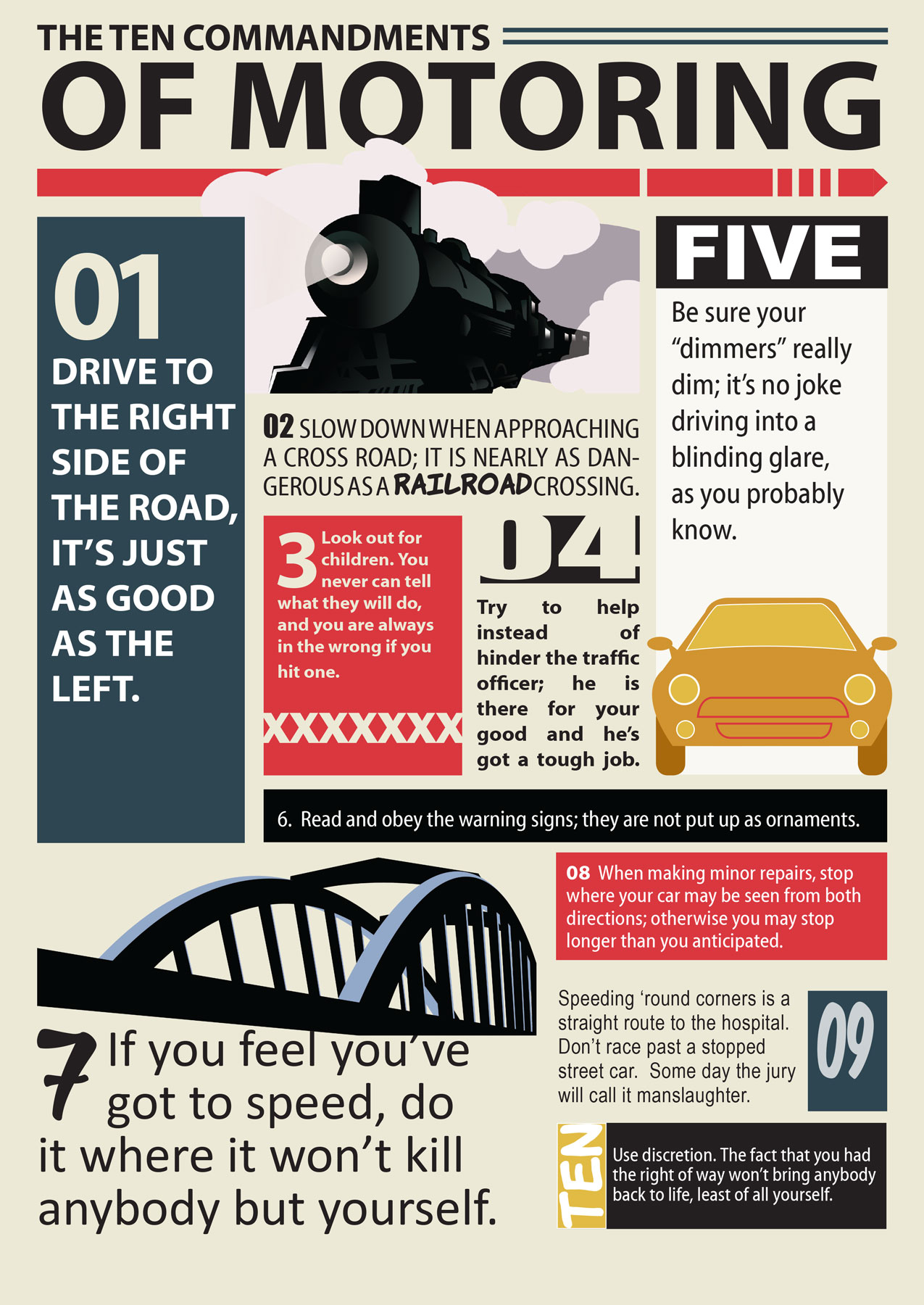

Minot residents soon took steps to adapt their city to automobiles. By 1925, Minot had 5.5 miles of paved streets. Three major highways intersected in Minot: the Theodore Roosevelt Highway (today this is U.S. Highway 2), the North Star or Great Green Trail (today’s U.S. Highway 52), and the International (or Black) Trail (today’s U.S. Highway 83). These highways brought local traffic and tourists from others states to Minot. With hundreds of local drivers as well as visitors on the highways, Minot needed to control traffic. Early in 1920, the city placed a traffic signal at Main and Central, but drivers did not pay attention to the lights. A second traffic light was installed in 1939, at 4th and north Broadway. Still, drivers had to be cautioned to be patient while waiting for a light to signal their turn to enter the intersection. Pedestrians also had new lessons to learn about cars on city streets. Careless drivers who hit pedestrians were generally not charged with a crime; it was only an “accident.” However, the old rule about pedestrians having the right-of-way on city streets was about to change. (See Document 8.)

By 1921, cities all over the country were training pedestrians to watch for cars. Some cities started “jaywalking” campaigns. The word “jay” was commonly used to describe a rural person who didn’t understand city ways. Cities were purposefully labeling people who crossed streets without looking for traffic as “country bumpkins.” To promote new ideas about pedestrians and cars, cities asked the Boy Scouts to stand at street corners and hand out fliers to encourage pedestrians to wait for an opening in traffic, or wait for the light to change. (See Document 9.) By the 1930s, cars controlled city streets and “jaywalkers” had learned to watch for traffic.

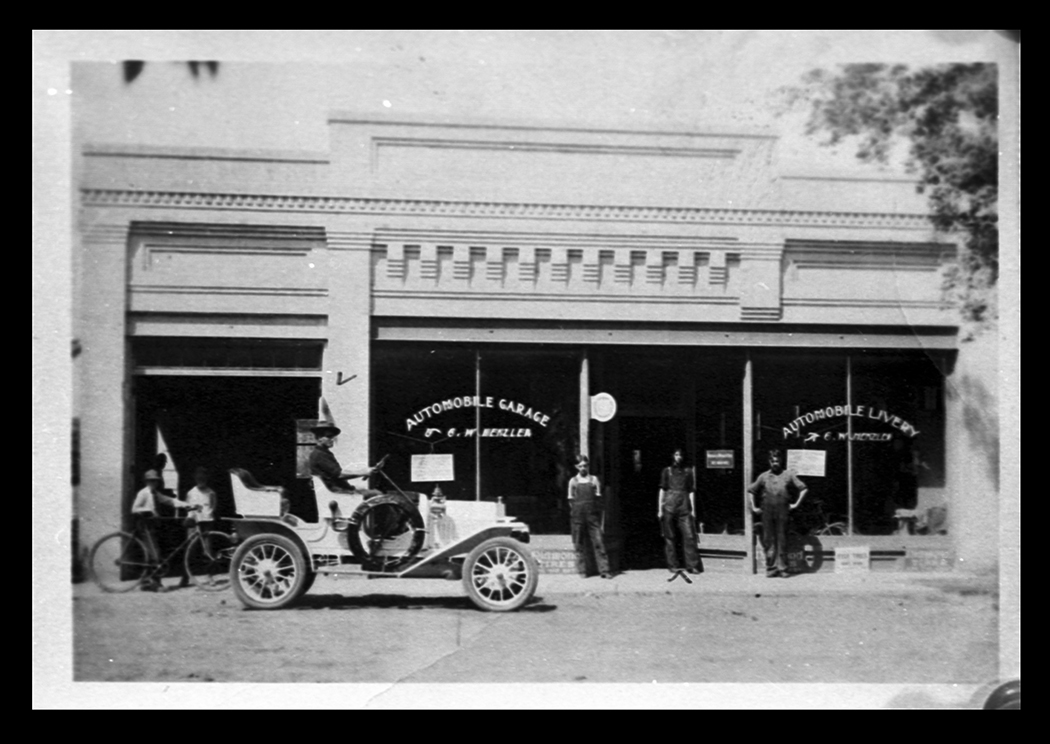

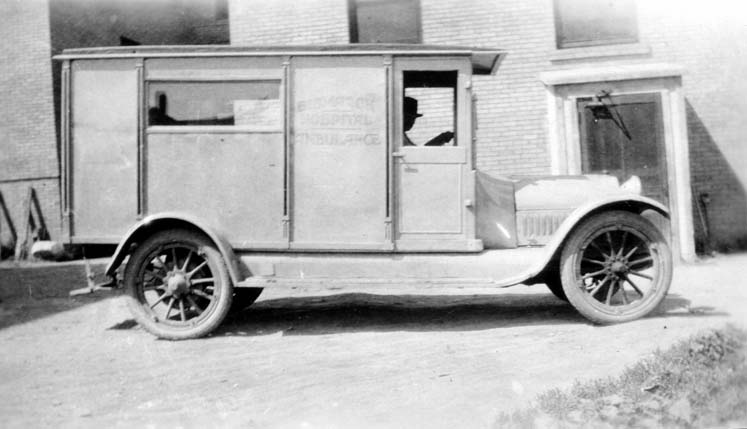

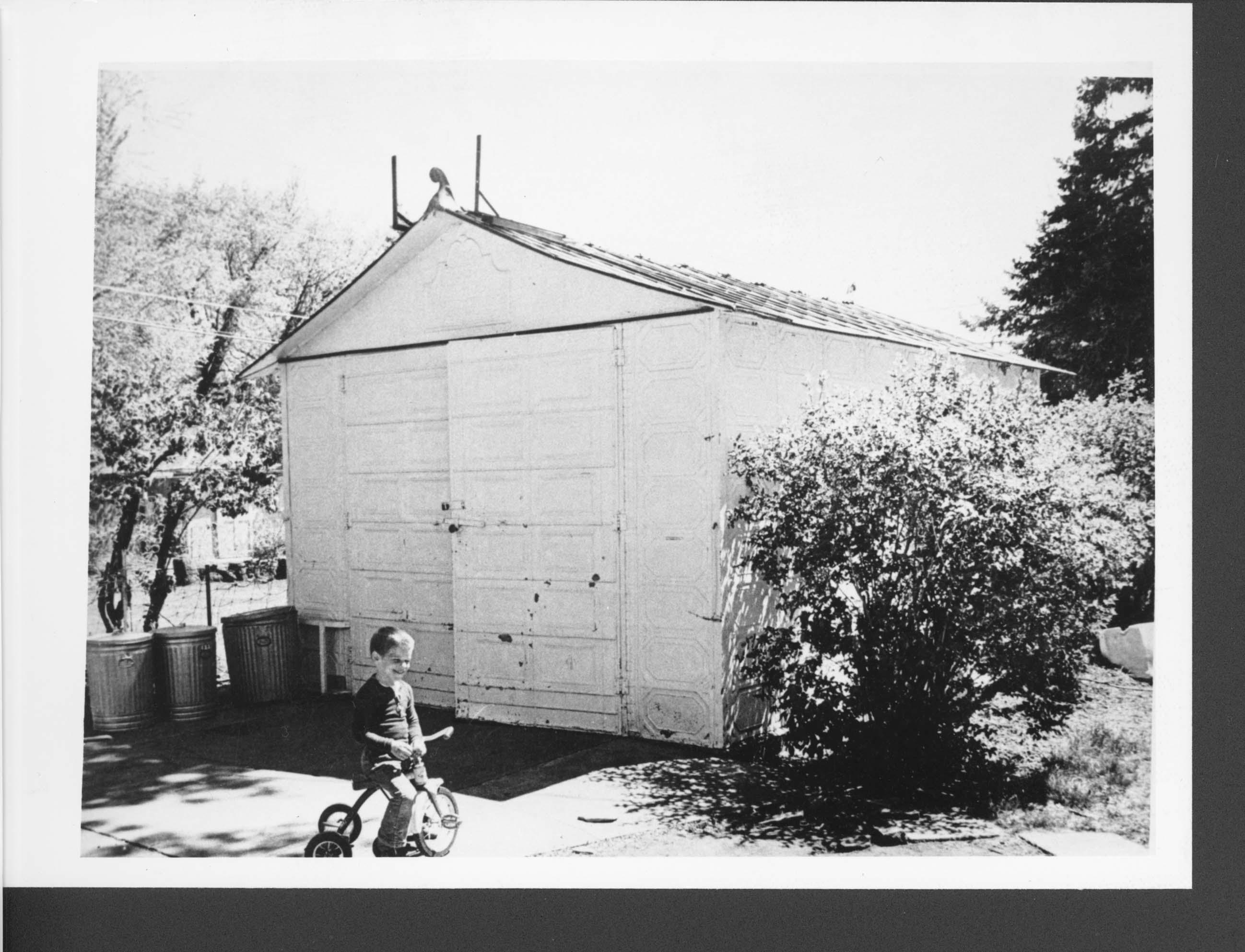

Cities found many advantages in the new gasoline powered vehicles, particularly ambulances and fire trucks. (See Image 21.) By 1910, fire engines were quickly replacing horse-drawn fire carts. Automobiles left city streets cleaner than horse-drawn vehicles. As city residents gave up straw-filled barns for automobile garages,In 1912, a Fargo business developed garages for homeowners who owned cars. The Rusk Auto House was a pre-fabricated, build-it-yourself, garage made from embossed tin and wood panels. The panels were shipped from Fargo to buyers around the state to be constructed on site.

The Rusk Auto House was not the first garage manufactured in North Dakota. Jacob J. Richter of Wahpeton had designed and patented a garage in 1911. However, the Rusk Auto House easily took over the market. Fargo Cornice and Ornament ceased manufacturing Rusk Auto Houses in 1915 when war in Europe (World War I) made it difficult to buy sheet metal. Fargo Cornice manufactured about 50 Auto Houses before 1915. Many can still be seen in several communities as well as the State Museum in Bismarck. the fire danger diminished. (See Image 22.) All cities enjoyed greater business opportunities that came with people traveling in cars.

Why is this important? Automobiles transformed city landscapes quickly. Owners of cars urged cities to pave the streets and install parking spaces. Private homes built garages to store automobiles. People traveled by car from rural areas to larger towns which caused smaller towns to lose business. School children rode busses to bigger schools in larger towns. Gradually, cars brought about growth in larger towns while small towns began to lose population and business.