Cars held immediate appeal for North Dakotans. Doctors, businessmen, and farmers bought cars, and then bought new or better cars. Some people built their own cars. However, one problem faced drivers that had to be solved by state, county, and city governments. That problem concerned roads. Though cars could travel on wagon trails in good weather, mud and snow stopped cars in the tracks. In North Dakota we have a lot of mud and snow. (See Image 10.)

The push for improved roads came from two surprising sources. Bicyclists had been campaigning for better roads for years. People who toured the country on bicycles or used bikes for everyday transportation in towns and cities wanted better road surfaces and a better system of connected highways. Bicycles, more so than automobiles, required good roads.

Railroad corporations were also asking for better roads. (See Image 11.) Railroads supported the development of better roads and highway systems in order to bring more business to railroads and railroad towns. A railroad executive encouraged states to put more money into roads when he said that railroads were the “arteries of the nation and the roads its veins.” In 1902, the Great Northern Railway sent a “good roads” demonstration train along its line. Where the train stopped, people from nearby towns and farms were invited to observe the newest road building equipment and techniques. Unfortunately, the train toured during harvest season and the weather turned bad. The demonstrations did not draw the expected crowds. After 1900, “good roads” organizations popped up in every state, including North Dakota. (See Document 6.) The organizations emphasized the advantages of auto tourism and the economic benefits to farmers of good roads. In addition, national organizations promoted the development of national highways funded largely by federal money. Some of the earliest national highways cut through North Dakota. One was called the Theodore Roosevelt International Highway, but many locals referred to the road as the T.R. (See Image 12.)

The T.R. highway closely (but not exactly) followed the road that today is U.S.Highway 2 from Grand Forks through Minot to the Montana border. The T. R. through North Dakota was constructed in 1919. However, “construction” meant something very different then. The road was not paved, only graded where necessary. (See Image 13.) The road was marked with signs and shown on Rand McNally road maps. The T.R. signposts had a red band with white borders. The letters T.R. were written in white on the red band. For all of its glory as a national highway, many drivers referred to the road as the “tough and rough” highway.

(See Image 14.) Other national highways included the Red Trail (later U.S. Highway 10 and now I-94) or the National Parks Highway which went through Fargo, Bismarck, and Medora. (See Document 7.) In 1912, some businessmen in South Dakota came up with the idea to build a highway to Yellowstone Park in Montana and Wyoming. The highway was called the Yellowstone Trail (today it is U.S. Highway 12). Travelers along the way stopped in Hettinger, Haynes, or Rhame, to spend the night or have a meal. The trail was marked with posts or stones that had “Yellowstone Trail” written on yellow paint with a black arrow. Sometimes the marker was simply a rock painted yellow. (See Image 15.) The Yellowstone Trail Association encouraged towns, counties, and states to make improvements on the road and provided maps that helped travelers find river crossings and services.

Document 7: Old Red Trail

There were 59,332 miles of public roads in North Dakota by 1906. Of course, many of these were slightly improved wagon roads. Only 205 miles had a gravel surface. The rest were simply areas where the prairie grasses had been scraped away so that wheels ran over dirt. There were few bridges over North Dakota’s rivers and creeks. Drivers crossing major rivers such as the Missouri had to go to a dock where they could find a ferry. (See Image 16.) When drivers approached a small river or a creek, they looked for a crossing where they could drive the car through water to the other side. (See Image 17.)

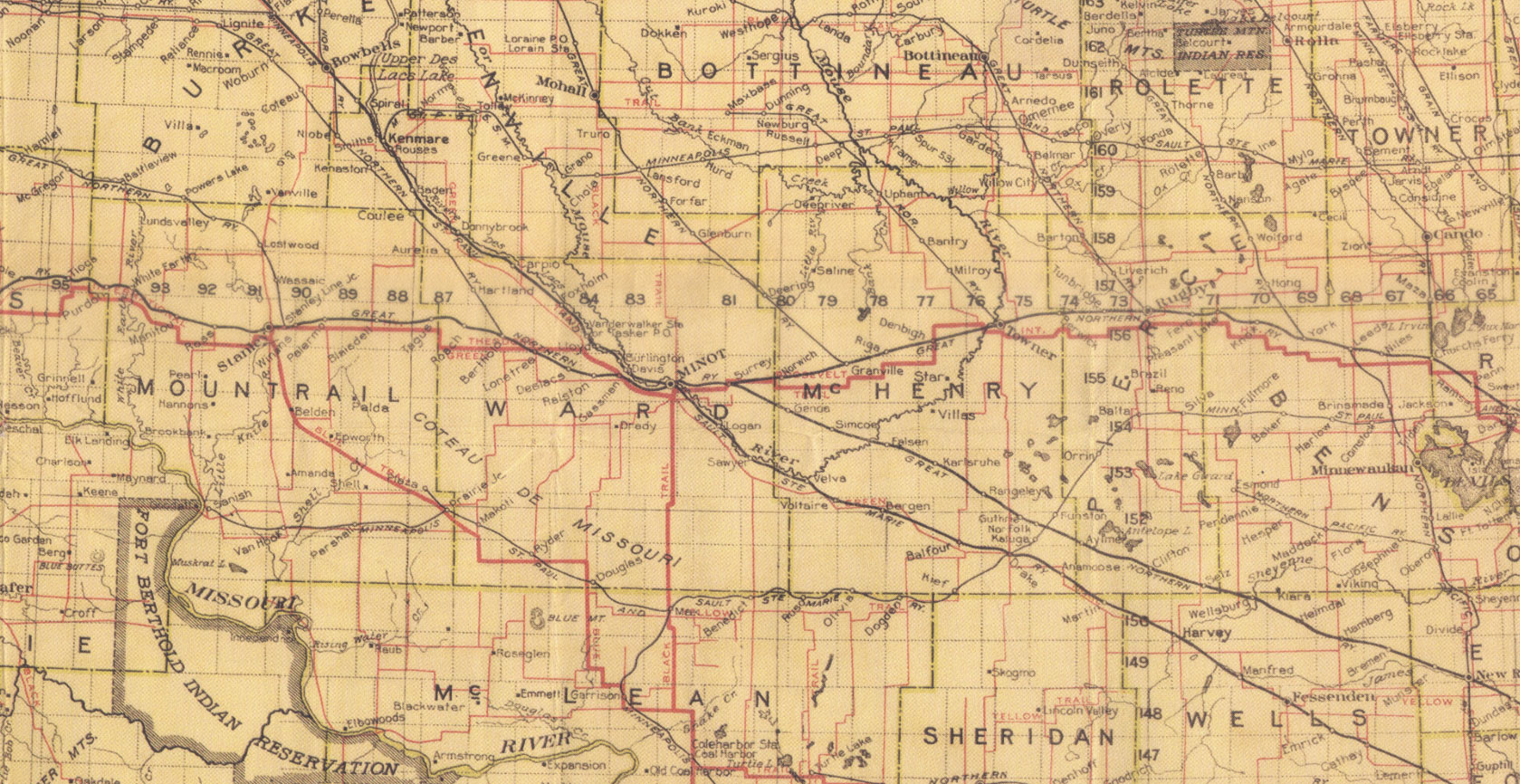

North Dakota established the State Highway Department in 1917. Between 1917 and 1924, the state built 2,366 miles of highways and linked them to highways in bordering states. In 1924, the Highway Department began to issue state highway maps. State highway construction received a boost in 1921 with the Federal Highway Act. The federal government took responsibility for some highways that crossed state lines, such as U.S. highways 2 and 12. However, the economic downturn of 1920 put limits on the highway budget. By 1927, only 10 miles of state and federal highways in North Dakota were paved and 1,338 miles were graveled. The rest of the roads remained dirt trails or graded dirt roads. In 1921, the Green Guide, an important source of travel information, pronounced North Dakota to be “well supplied with good roads.” (See Map 1) Most residents knew that the Guide overstated the case when it announced that “prairie soil makes a wonderfully durable and easily maintained road, under moderate traffic.” Had the Guide admitted that prairie soil also makes a great mud puddle after a moderate rain, travelers would have been better informed about highways in North Dakota. (See Image 18.)

Why is this important? Many North Dakotans, especially farmers, thought that automobiles might be a passing fad. They were reluctant to pay taxes to support the building of improved roads. However, railroad support for improved roads, the enthusiasm of car owners, and the development of highway associations led to the improvement of roads in North Dakota. The roads connected towns which benefitted from increased business. Farmers benefitted because roads made their long trips to town with grain or cattle much smoother and faster. By 1920, no one believed that cars would disappear. Highways were literally the road to the future.