Historians often use documents, words written on paper, to examine the past. Objects can be used as historical “documents,” too. Toys are one way of looking at childhood in the past to find out more about what society valued and the role that children were expected to play in their families and communities.

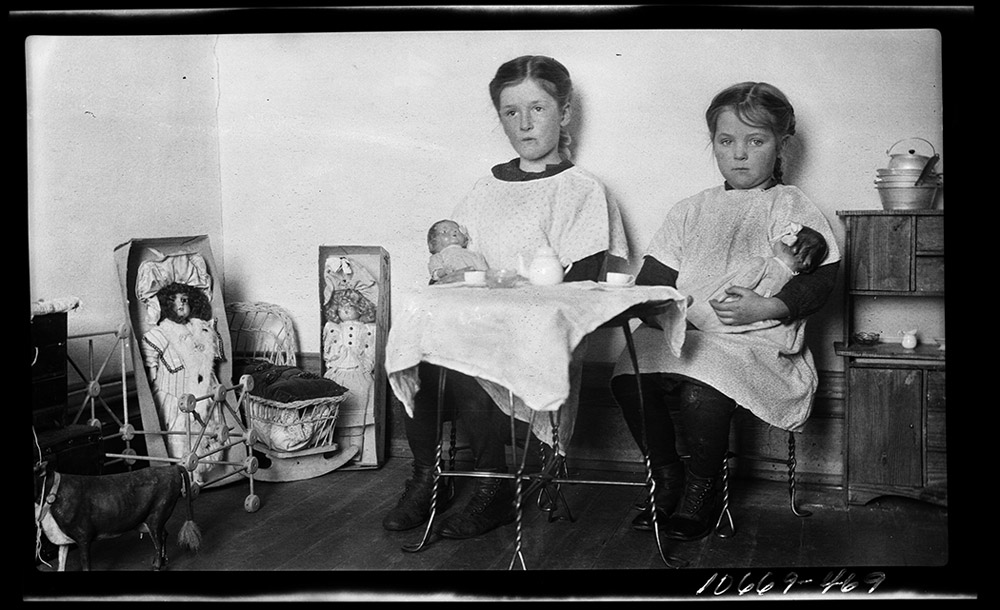

Toys are often gendered. This means that they are usually directed specifically toward boys or girls. Gendered toysToy designers usually have a clear idea about how a toy should be used, how it will be marketed, and what parents can expect when they give a toy to their children. However, children often re-imagine a toy by ignoring the goals of designers, marketers, and parents by using toys in some other way. For instance, a little girl might use a truck to transport her dolls and all of their clothing around the house becoming, in her imagination, a truck driver instead of a “mommy” to her dolls. are designed to teach boys and girls about the roles they will have as adults. For hundreds of years, toymakers, parents, and teachers assumed that men performed certain kinds of jobs and had a certain role in the family. (See Image 3.) The same assumptions were made about girls and women, but the jobs and roles were different from men’s.

Toys also reflect economic changes in society. For instance, 19th century boys often wanted to be train engineers, but little boys in the late 20th century wanted to become astronauts. Toys were made to meet the ideals of the time period.

Toys explain many things about childhood, but children who grew up in poor families often did not have new or expensive toys-or perhaps any toy at all. (See Image 4.) Poor children made dolls from rags filled with straw. Many children had home-made wooden building blocks or small, hand-carved trains. Children found ways to play games and make toy objects from things they found near their homes. Ward Wilson, remembering his childhood in Valley City during the 1930s wrote:

The hills and ravines taught us all kinds of things we did not learn in school. The creative juices of childhood flowed more freely without the [manufactured toys] of the more prosperous times before and after the ‘30s. We kids learned to use all the opportunities that surrounded us in our town and in our hills, river, and vacant playground lots. The fun was generated by us, and it was real!

Jim Oberfoell who grew up in a sod house in southwestern North Dakota in the 1930s had similar memories of growing up without toys:

Star formations in the sky were my companions. I made up names for them because we had no books on such. Many years later, I learned that what to me was a boy with a kite on a string was actually Orion.

In the late 20th century, some toymakers responded to new ideas about roles for men and women at work and at home. Male figures, usually called “action figures,” were marketed as toys for little boys. These action figures were much like dolls, but many people still did not like the idea of boys playing with dolls. However, boys could imagine an acceptable adult male role through action figures. Little girls’ dolls changed, too. Girls played with “Barbie” dolls that were full-grown women figures, not babies. Barbie reflected adult roles for women that involved careers outside of the home. (See Image 5.)

Society changed a great deal between 1920 and 2000. However, the important fact of childhood remained constant: children learn about life through play with toys or in a world of made-up toys and games. Toys helped teach children what they needed to know when they grew up.

Why is this important? Childhood play and toys are one way to study the history of social and economic elements of society. Toys as objects document the history of childhood, but to fully understand how children experienced their world, we need to understand how children played with their toys. Children imposed their own views on toys and games. As they re-imagined their toys, children re-interpreted gender roles and the social levels created by wealth. The child’s world is always a world of possibilities.

Sources: Ward Wilkins, “And Some Went Hungry”: A Town Kid’s Memoir of the 1930s (2002); Jim Oberfoell, “Childhood inside a sod house,” Bismarck Tribune 9 October 2011, page 10A.