There is no doubt that Great Depression of the 1930s brought very hard times to North Dakota. Even those considered relatively well-off had to make great sacrifices and manage their money carefully. The eastern part of the state did not experience drought as severe as that in the western part of the state. Many farmers were able to harvest a small crop. However, Fargo attracted people who left their farms because the farm could no longer support the family. In the state’s largest city, people went hungry, struggled to pay their bills, and became deeply discouraged.

-optimized.jpg)

Frieda Oster left her farm home to study business in Fargo. Because she was not married, she was able to find a job as a bookkeeper at a clothing store. She rented a cheap room in a private home, but still had trouble paying her bills. On March 17, 1937, she had only “53¢ to live on until 1st” of April. In 1938, she sat down and cried when she realized she could not pay her grocery bill of $9. Had Oster married, it is likely that her employer would ask her to give up her job.

Frieda Oster held a job that required education and skill. Women without skills worked as housemaids (domestics) or waitresses for as little as 20 cents an hour. There was a state law requiring employers to pay women at least $14 per week, but many employers simply ignored the law. One café owner paid waitresses $4 per week plus meals. Employers could get away with such abuses of the law and their workers because their employees had few options.

Some federal employment programs included women. The WPA hired women to sew clothes for the poor. Women participated in the WPA pottery program and the writers’ program. The CCC, however, purposefully excluded women. Many employers would not hire a married woman. These employers assumed that only one person in a household was entitled to a job and that should be the man. Many people thought that a married woman should not take a job that a single woman or a man needed.

Throughout most of American history, charity was a local responsibility. (See Image 14.) In North Dakota, township governments provided fuel, food, and sometimes other expenses to poor families. Several counties maintained homes for the poor and disabled. Churches and other charitable organizations such as the Red Cross also contributed to the support of the poor.

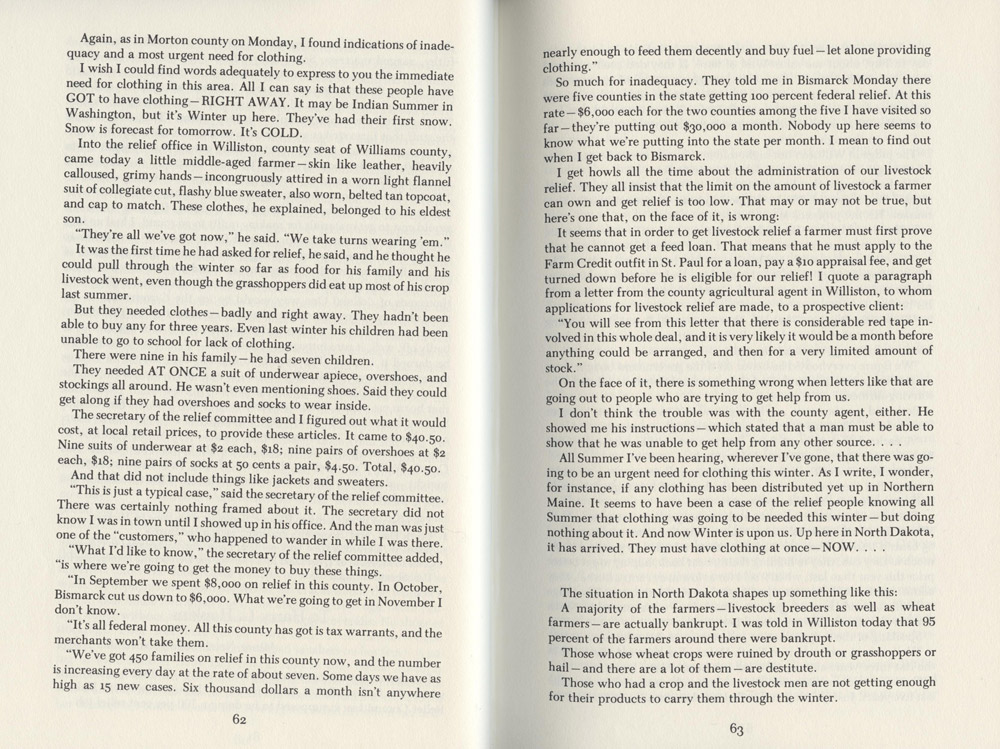

As the depression deepened, local resources were exhausted. (See Document 4.) The counties could not collect the taxes needed to fund relief (support of the poor). Churches soon spent all of their charitable funds helping the poor. Still, there was not enough food, clothing, and fuel to help all the families that needed it.

After Franklin Roosevelt was elected president, he encouraged Congress to pass several bills to provide direct charity (relief) and to create jobs, to support farmers, and to stabilize the economy. The Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) distributed funds to the states to be used to provide direct relief of food, clothing, and fuel to needy people. (See Document 5.)

North Dakota formed a Relief Committee to distribute federal relief funds. (See Image 15.) The funds were slow to arrive, and many local committees did not have a good plan for distributing food and clothing. Even though the Depression was widespread and suffering was great, many people still believed that somehow the poor had brought their problems on themselves. Members of relief committees often restricted funds to those who seemed worthy of charity. (See Document 6.)

Private charity continued to provide for the poor when possible. Northwood (Grand Forks County) residents worried about the farmers in western North Dakota who had been having hard times since the early 1920s. In September, 1931, Northwood folks decided to fill a railroad car with potatoes to send to western North Dakota. In Northwood, where the drought had not been as bad, potatoes were a crop they could share. The newspaper announced: “We who have abundance to eat should be . . . glad to send a little aid to the unfortunates who had no crops at all and little or no garden produce.” One month later, Northwood sent seven train cars full of potatoes to the Red Cross in western North Dakota where they were distributed just before winter set in. Another railroad car full of vegetables was sent to Minot. The people of Northwood took pride in their contributions and were grateful that they had surplus to share.

Why is this important? In the United States and in North Dakota, citizens have had long discussions on the issues of poverty and charity. While most people believe that Americans should not suffer in poverty, they also believe that in the midst of abundance, everyone should be able to take care of themselves. Americans and North Dakotans have been engaged in a long debate about whether charity is the proper solution to poverty.

The Great Depression puts poverty into historical perspective. The history of the 1930s tells us that sometimes people are overwhelmed by economic forces they cannot control. The Great Depression also suggests that we cannot always expect farm land to be productive in the face of severe climate distress. Questioning some of these assumptions is a healthy process in a democracy. Unfortunately, there are no easy answers.