The Great Depression presented a set of challenges to North Dakotans that, at times, seemed to be completely overwhelming. The Great DepressionAn economic depression is defined by any combination of negative (non-growth) economic activities. A depression might occur because real estate or land values decrease or wages decrease. The price of goods (automobiles, for example) or services (mechanical repair of cars) might decrease. On the other hand, the price of automobiles might stay the same, but if wages decrease and people can’t afford to buy cars, automobile manufacturers will lose money and lay off workers. In a serious depression such as the Great Depression of the 1930s, almost every economic factor was depressed. Factories closed or laid off workers, sales in everything but groceries diminished, and land values dropped. People bought necessities such as food and medicine on credit. Grocers could not pay their own bills because they did not have cash coming in to the store. An economic depression tends to have ripple effects throughout a community which makes it very difficult to “fix” the causes of the depression. was the result of a complex of problems that could not be easily solved. Each problem seemed to generate more problems. Every thoughtful effort to find a solution failed. In addition, the economic problem was complicated by an extended and intense drought. It is no wonder that so many North Dakotans simply gave up.

To understand the impact of the Great Depression (1929-1940) on North Dakota, we need to understand the situation of both farmers and bankers in the 1920s. During World War I (1914-1918), the price farmers received for wheat, beef and other farm products (commodities) rose above the cost of production. Farmers enjoyed having extra income. Many farmers borrowed money to buy more land. However, after the war, agricultural prices fell. In 1930, farmers received about 60 cents per bushel for wheat which was 17 cents less than it cost to produce a bushel of wheat. (See Image 1.)

In addition, drought began to appear in the 1920s. About every third year, drought limited crop and hay production. Grass pastures dried up, and cattle did not have enough feed. Farmers needed to sell more agricultural products to make up for low prices, but because of the drought, they had less to sell.

At the same time, counties were raising taxes on real estate and farm land. Taxes more than doubled by 1922 and did not decline very much during the 1920s. Low agricultural prices and high taxes tended to make the value of farm land fall. A farm that was worth $41 per acre in 1920 was worth about $13 in 1940. Farm land values had dropped by 68 per cent.

As the tax burden increased and prices fell, farmers turned to banks to make up the difference between their income and their needs. Banks lent money to farmers based on the value of their land. This type of loan is called a mortgage. If a farmer had 100 acres worth $40 per acre, a bank would usually lend the farmer a little less than the total value ($4,000). The farmer had to repay the loan by making payments every year. If the farmer failed to repay the mortgage loan, the bank could foreclose on the mortgage which means the bank could take title to the land. (See Document 1.)

North Dakota banks were chartered by the state or by the national government. State banks could open with only $10,000 in assets (cash). In 1920, there were 898 national or state banks in North Dakota. Banks made money by charging interest on loans. They used the money deposited in checking and savings accounts to make loans. It was important for banks to make sure that they had enough cash on hand and that the total amount of loans did not exceed 60 per cent of the deposits in savings and checking accounts.

Unfortunately, North Dakota banking laws were not strict. Banks made too many loans during the 1920s that could not be repaid. Farmers who had little income began to draw their savings out of the banks. Bank deposits decreased, and banks foreclosed on de-valued farm land. As banks lost money, they had to borrow money from large Minneapolis banks to maintain their cash levels. Those loans had to be repaid with interest. Unable to make payments, 99 banks went out of business in 1923. The banks could not collect on mortgages, and their depositors could not get their money out of the bank. More banks closed over the next few years. By 1933, 573 North Dakota banks had closed. Farmers could not borrow money; many lost their farms. (See Image 2.)

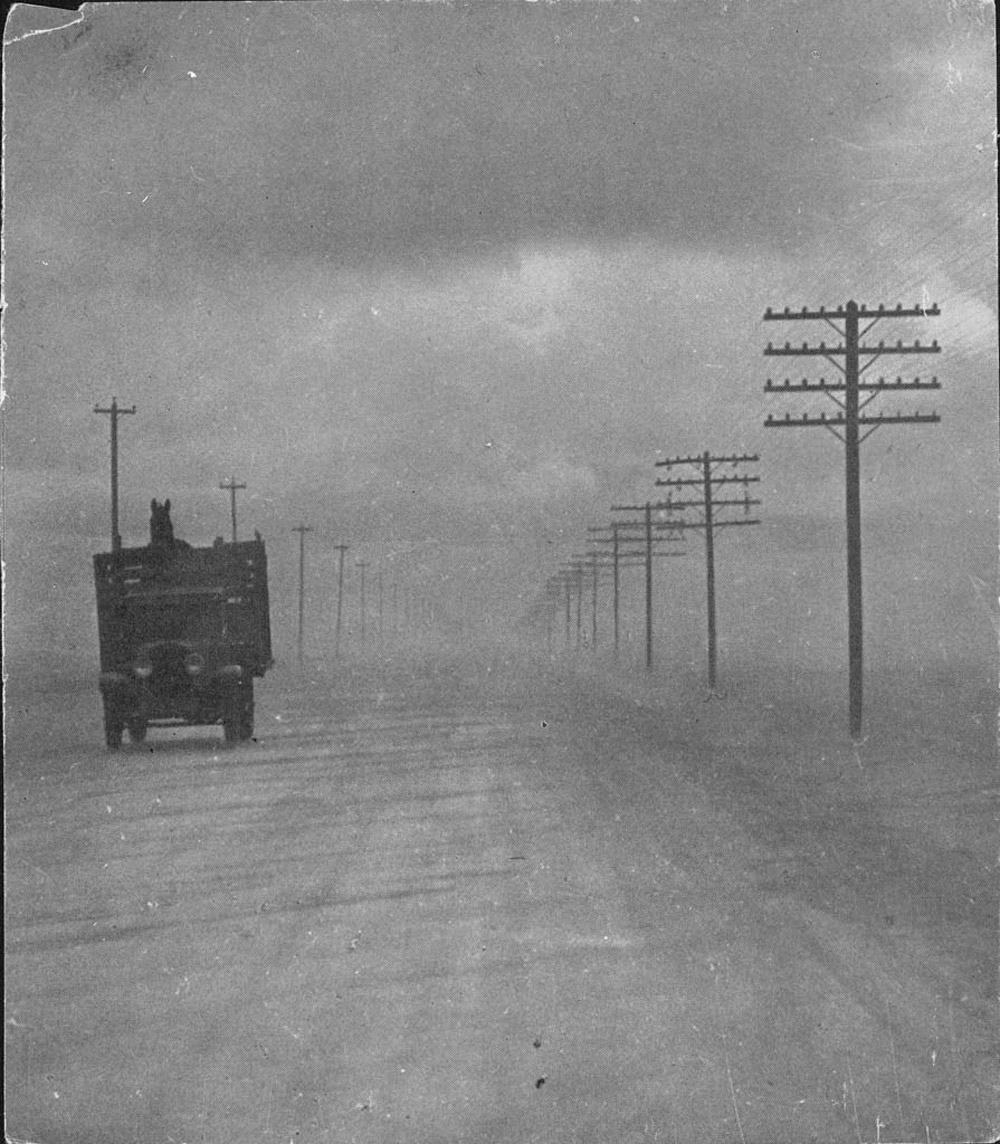

The Great Depression of the 1930s coincided with a long, intense drought in the Great Plains. (See Image 3.) Most of North Dakota suffered serious drought during the 1930s. When a little rain came along, it was often not enough to make up for the many months of drought that came before the rain. Crops dried up, and hay would not grow. (See Image 4.) Some farmers made hay with thistle to feed their cattle even though cattle won't eat thistle unless they are very hungry. Because there was no rain to wash away the grasshopper eggs, many farm crops were completely destroyed by clouds of grasshoppers. The grasshoppers were so hungry that they ate brooms and clothes on the clothesline once they had finished with the crops.

All of these factors contributed to making the experience of North Dakotans in the 1930s among the worst in the nation. By 1929, the North Dakota per capita (each person) income was $375. This was a little more than half of the national average of $703 per year per person. Low income, heavy debt, and very cold winters were more than many people could withstand. The populationThe population of North Dakota reached a peak in 1930 and then began to fall. During the ‘30s, more than 80,000 people left the state and the population continued to drop over the next several decades. The 2010 census indicated a count of 672,591 people. The growth was attributed to the oil boom. The census estimates that in 2013, the population of North Dakota reached 723,393, surpassing the population peak of 1930. dropped during the 1930s and did not recover until 2013.

Why is this important? When farmers began to settle North Dakota in the 1870s, it seemed they could not fail. The soil was fertile, banks offered cheap loans. Wheat was king. There were some hard times, but the best farmers were tough enough to pull through until the economy improved.

By 1930, it appeared that it was a mistake to be so optimistic about farming in North Dakota. A long drought or a spell of bad farm prices was enough to make even the best farmers fail. In the 1920s and 1930s, the combination of low prices, poor crops, and bad weather drove many farmers off the land.

Those who continued to farm saw many changes. They participated in federal farm programs. Farmers developed new methods of farming to conserve moisture and restore fertility to the soil. Some banks reopened in 1933 with stricter lending rules and better supervision from the state. Fewer people lived and worked on farms as farms became larger and more productive.