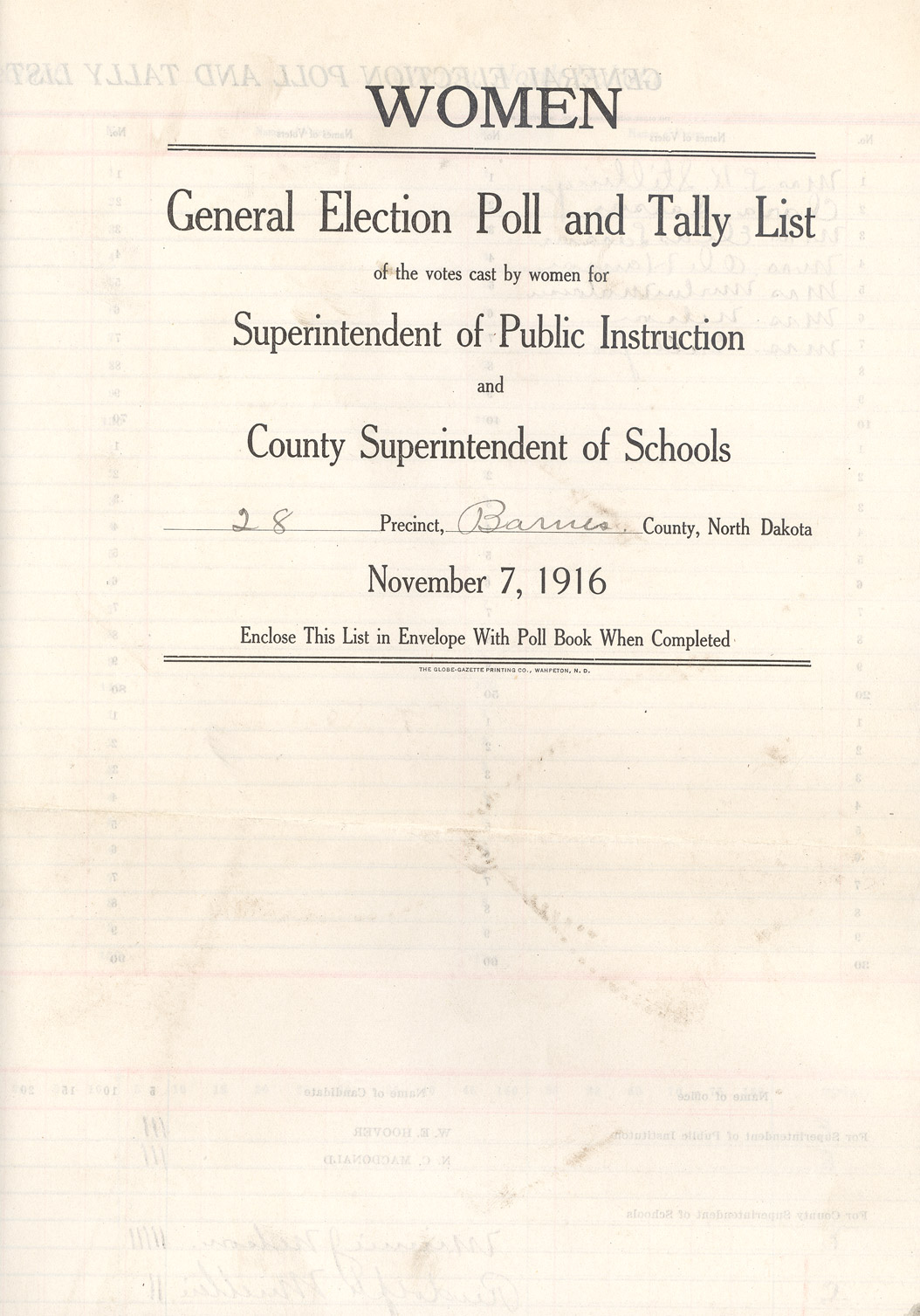

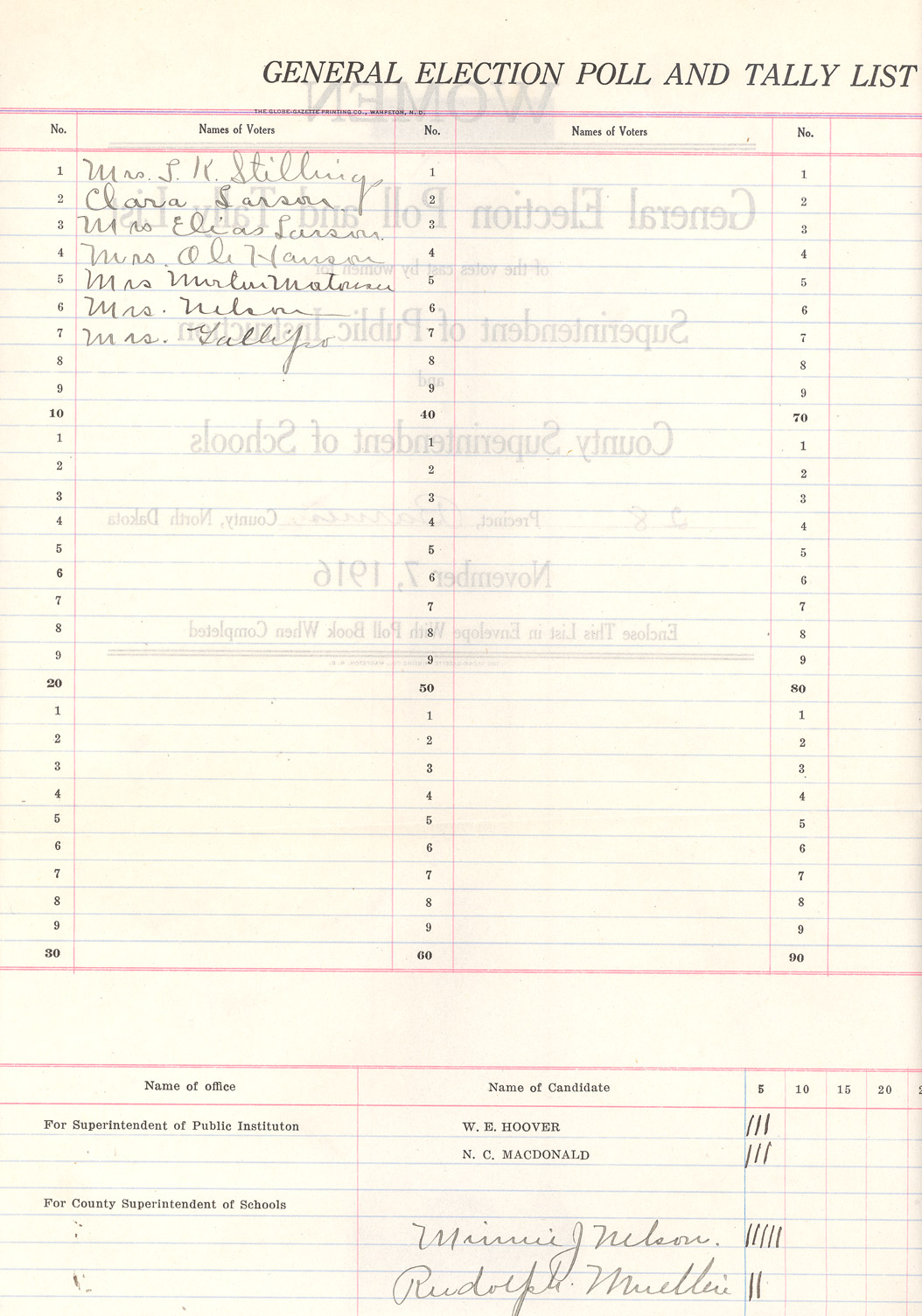

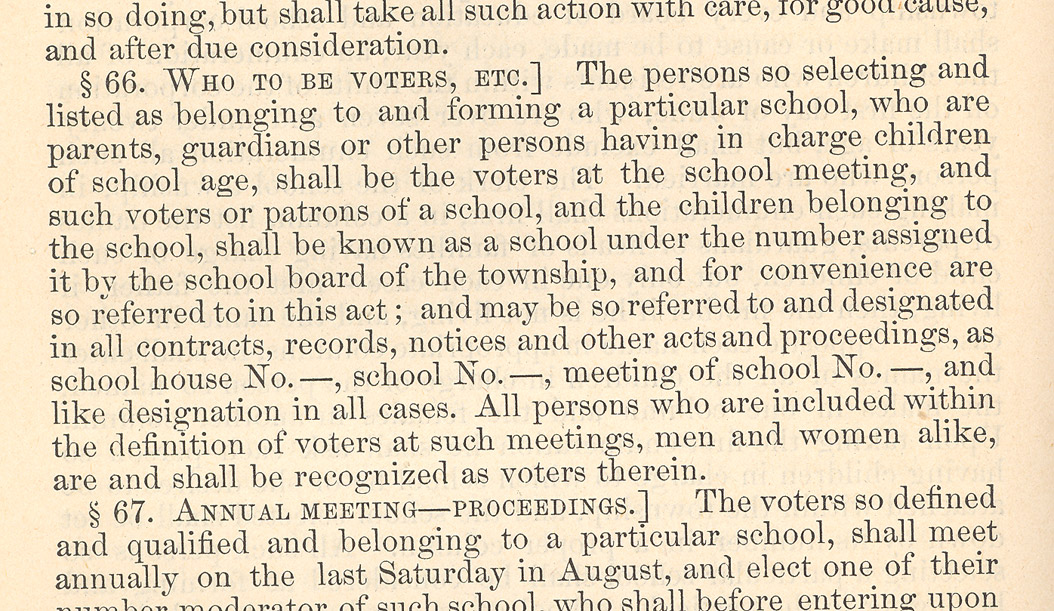

The women of Dakota Territory did not have the right to vote until 1883, even if they owned land or paid taxes. Woman suffrage was an important topic in Dakota Territory and proposals for full suffrage were brought up in legislative sessions from time to time. The women of Wyoming Territory had enjoyed full voting privileges since 1869. Finally, in 1883, the Dakota Territorial legislature cautiously granted school suffrage to women. This meant that women could vote on all local school issues. (See Document 1) When North Dakota became a state in 1889, school suffrage continued and women could vote for state Superintendent of Public Instruction. (See Document 2)

From 1870 to 1912, suffrage was a movement with strong leaders, but few followers. Woman suffrage was a national issue, and many legislators and civic leaders believed that women’s votes would be politically important. Many suffragists believed that women’s votes would contribute to keeping North Dakota a “dry,” or prohibitionist, state. Suffragists also believed that women’s votes would contribute to a more moral and serious atmosphere at the polls. However, important and powerful business interests worked against woman suffrage, including the political “boss” of North Dakota, Alexander McKenzie. In addition, many men considered woman suffrage a joke.

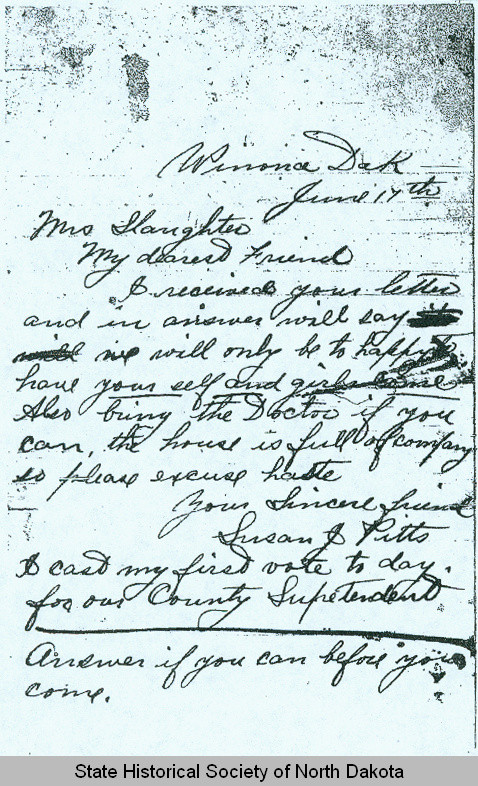

During the early territorial period, the leader of woman suffrage was Linda Slaughter.Linda Warfel Slaughter held elective office before she was able to vote. She was first appointed, and later elected, county superintendent of schools for Burleigh County. She held the office for four terms. She campaigned against as many as four men, but she won the office every time she ran for election. Slaughter was well-educated and an experienced teacher and school supervisor. She was vigorous in her efforts to educate Burleigh County children. Because she was a woman, her right to hold office was challenged. However, in 1874, the territorial Supreme Court said that there were no restrictions against a woman holding office, even though she could not vote for herself.

Ironically, Linda Slaughter declined to run for superintendent of schools after her last term ended in 1883. That was the year that the territorial legislature granted women the right to vote in all school matters. (See Document 3) By the time of statehood, Elizabeth Preston Anderson became the most important leader of woman suffrage. (See Image 1) Neither woman raised a ruckus over the issue. There were no suffrage parades or hunger strikes in North Dakota as there were in other states. Slaughter represented the National Woman Suffrage Association in North Dakota. Elizabeth Preston Anderson was president of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) in North Dakota. The WCTU’s most important concern was to maintain the prohibition clause in the state constitution. Incidentally, the members of the WCTU supported woman suffrage.

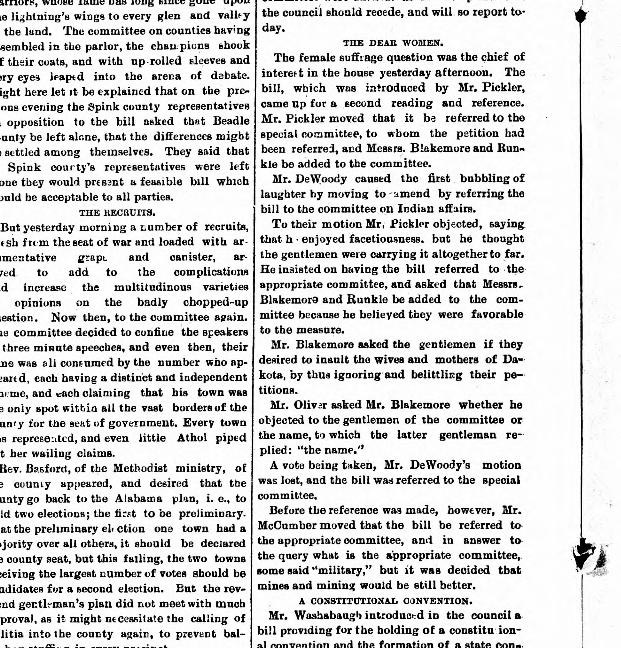

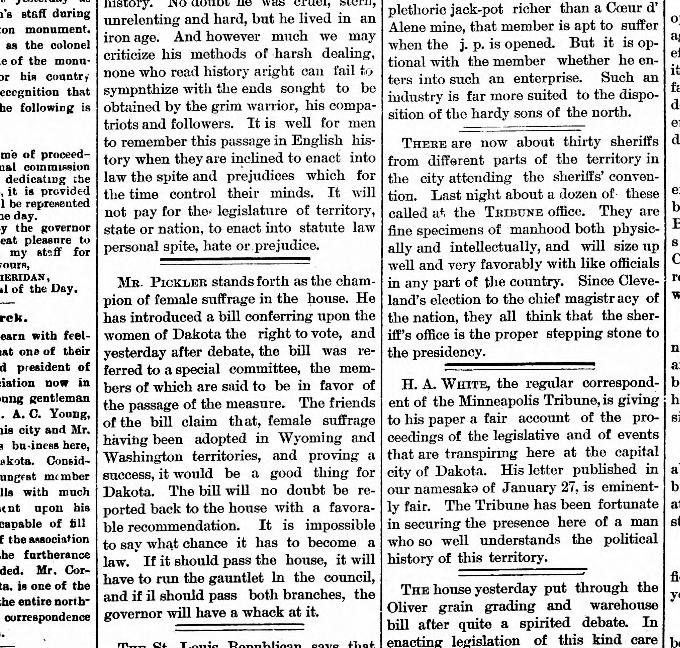

In 1885, a bill granting women full suffrage was introduced into the legislature. A few legislators viewed the bill favorably. Newspaper editors in the northern part of the territory supported the bill. Many letters written to the Bismarck Tribune urged the legislators to approve the bill. (See Document 4) However, other legislators treated the bill as a joke. In an effort to discredit women’s arguments for equality, they tried to refer the bill to the Indian Affairs committee. This move, though a joke, demeaned both women and Indians.Legislators who opposed woman suffrage often linked women’s voting rights with the expansion of suffrage to Indians and African Americans who usually did not share in the benefits of democracy. This bill passed both houses of the assembly but was vetoed by Governor Pierce.

A woman suffrage bill was introduced at the last territorial legislature in 1889. This time, Mrs. Anderson was watching the events in the legislature very closely. She recalled one of the arguments raised by a legislator against the bill. He said: “If that bill becomes a law, every Norwegian woman in the state will vote and there won’t be a white woman in the state that’ll vote, and the result will be that in a few years not a man can be elected to the legislature unless he’s a Scandinavian.” Of course, today we understand that Scandinavians are light-skinned people, but in the 19th and much of the 20th centuries, immigrants were often not classed as “white” people.

Mrs. Anderson was also present in 1893 when the state legislature was often at odds with the first Democratic governor, Eli Shortridge. In 1893, a bill to grant woman suffrage passed both the state senate and house on the last day of the session. The speaker of the House refused to sign the bill. Mrs. Anderson believed that Governor Shortridge would sign the bill. However, the bill was “lost” on the way to the governor’s office. (It was not the only bill “lost” in that noisy and unproductive session.) The House then expunged the record. This means that the House removed all notice of the bill from the minutes of its meetings. If witnesses had not remembered the event, no one would know that North Dakota nearly legalized woman suffrage in 1893.

Why is this important? Some members of the state legislature said that they could not support woman suffrage until women in substantial numbers asked for the right to vote. Their argument suggests that voting is not an inherent human right, but a gift of government to the governed.

The founding documents of the United States state otherwise. The Declaration of Independence declares “that Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.” The Preamble to the Constitution begins with the phrase: “We the People.”

The major legal question was not whether these documents considered women less than human, but whether women’s rights were covered by their husbands’ rights. Even single women were under the care of their fathers and brothers. When women asked for political equality, they were also asking for the right to govern their own business, legal, and social affairs.