The Great Plains seemed a strange place to many newcomers. The land had no forests. Many Americans who decided to take advantage of the Homestead Act went to the Great Plains from states with great forests. They had experience in building houses from trees. Trees also provided firewood, wood for furniture, and shelter from the sun and wind.

The lack of trees was evidence that less rain fellThe entire state of North Dakota has an average rainfall of 15.36 inches per year. Ohio has an average of 37 inches per year; Pennsylvania has 40 inches per year; Illinois has 33 inches per year. Even Nebraska (30 inches per year) and South Dakota (17 inches per year) receive more rain than North Dakota. on the Plains than it did in some places like Ohio or Pennsylvania. Some politicians and scientists believed that trees helped to create rainfall. They stated that the solution to the problems of lack of rainfall and lack of lumber for building and fuel was to plant trees.

Senator Phineas W. Hitchcock of Nebraska sponsored the Timber Culture Act, which Congress passed in 1873. This bill allowed settlers to claim an additional 160 acres if they would plant trees on 40 acres of that quarter section. The farmer had eight years to get all the trees planted. The trees had to survive for 13 years. After that time, if the trees were still alive, the farmer would get title to the land.

Farmers found the requirements of this law nearly impossible to meet. If rain did not fall in the year the trees were planted, they died. On the Great Plains, with its semi-arid climate, no one could count on enough rain to raise trees. The law required that claimants plant 2,700 trees per acre. Of those trees, 675 trees per acre had to survive the 13 year period for making final proof. The cost of the trees and the labor necessary for planting required too much of most farmers

Often, farmers and ranchers saw the law as a way to get free use of the land for 13 years. They filed a claim, but did not prove up. In the meantime, they could raise a crop or graze their cattle without investing in land or a house.

About 20 per cent of the homesteaders in all states and territories filed for a Timber Culture Act claim, or tree claim as they were commonly called. Because most of the trees died, few claimants made good on their claims. In northern Dakota Territory, 9,678 tree claims received title. The law went through a few changes to make it more reasonable. The number of acres of trees was reduced to 10. The number of surviving trees required for successful proof was also reduced. Finally, Congress repealed the law in 1882.

Why is this important? The Homestead Act did not grant farmers enough land to make a living on the Great Plains. However, farmers could add land to their Homestead Act claims through the Timber Culture Act. Then they had enough land to raise crops for a good income. With increased income, they could purchase more land. Some “tree-claimers” were allowed to commute their claims (pay cash for the land) after finding that the trees would not survive.

By 1900, farmers and scientists knew that trees would not create more rainfall. But farmers discovered that trees slowed the wind blowing across their farms and protected the crops. Farmers also discovered that a line of trees stopped blowing snow, causing snowdrifts that melted into their fields in the spring. Though the Timber Culture law was a failure, it offered farmers and ranchers the advantage of a little more land for a few years.

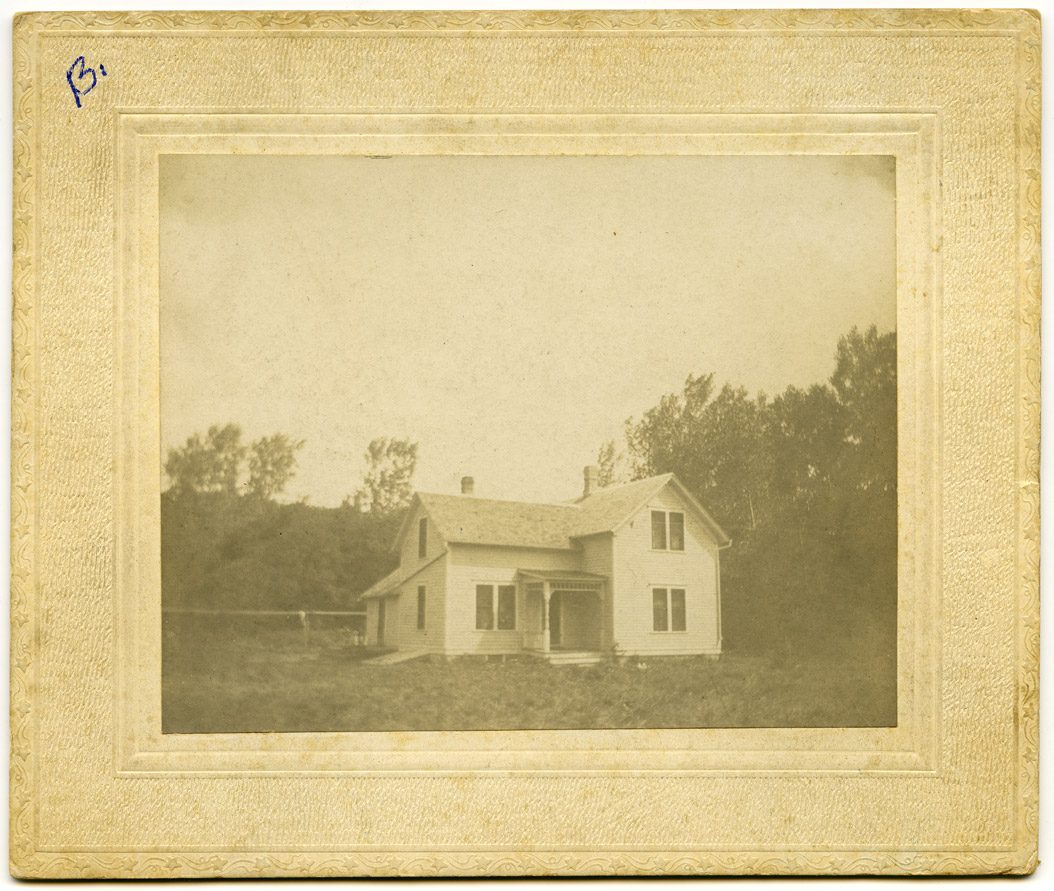

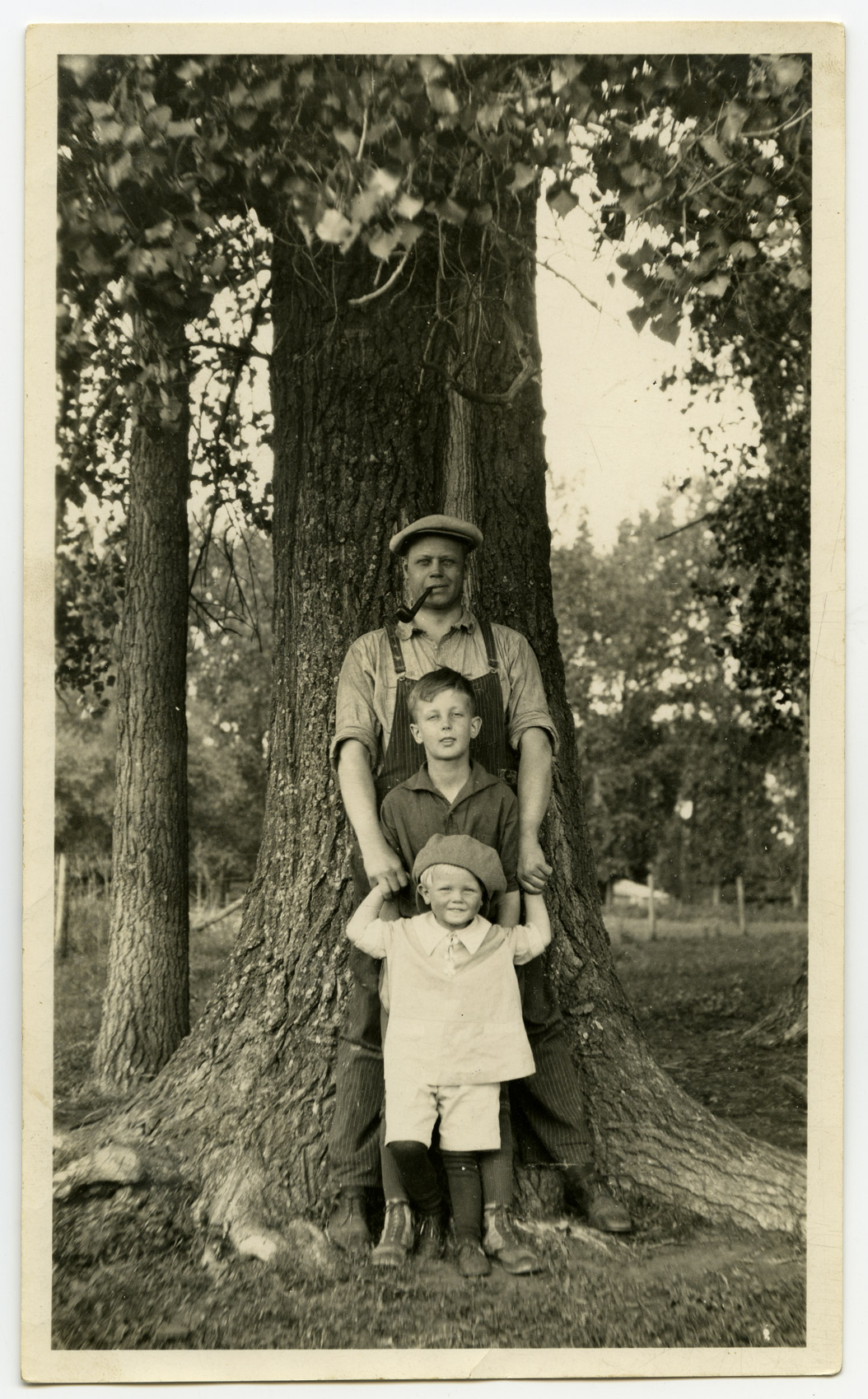

Wold’s Grove

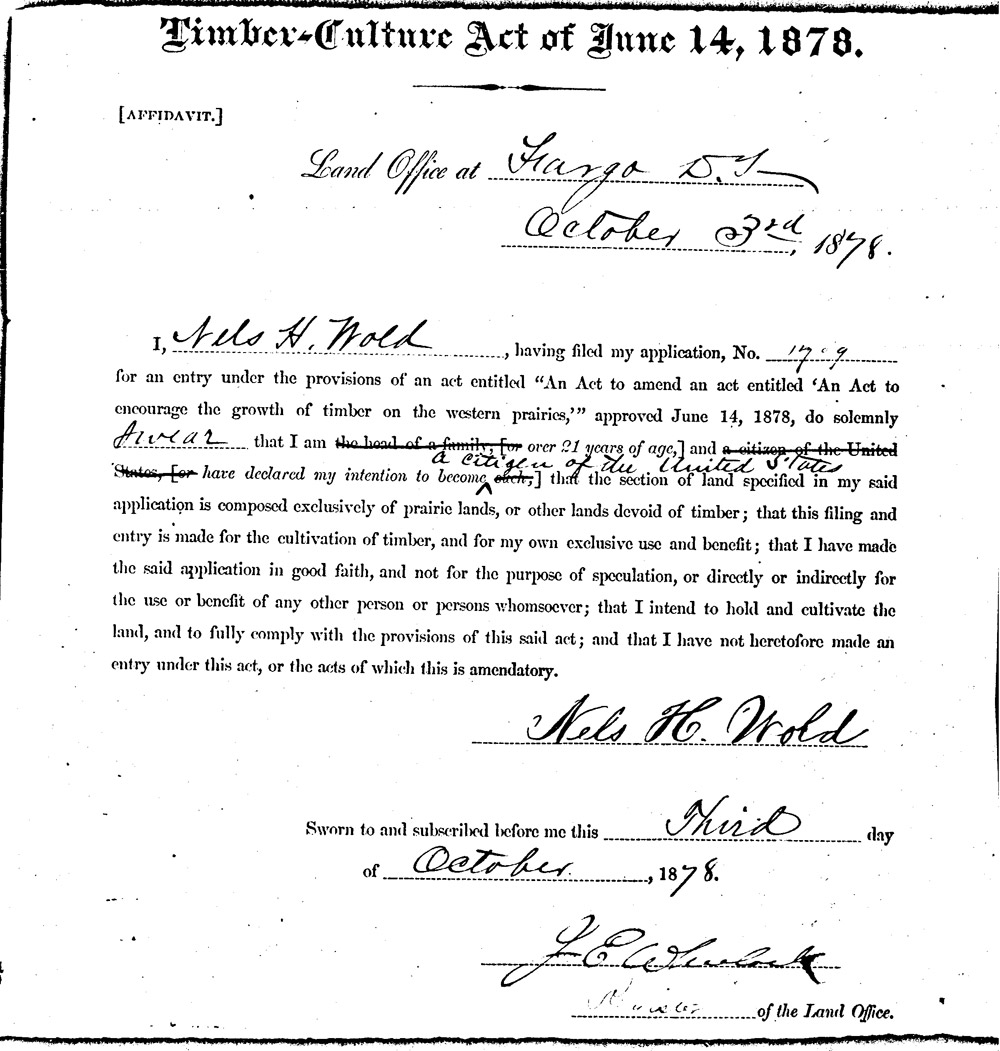

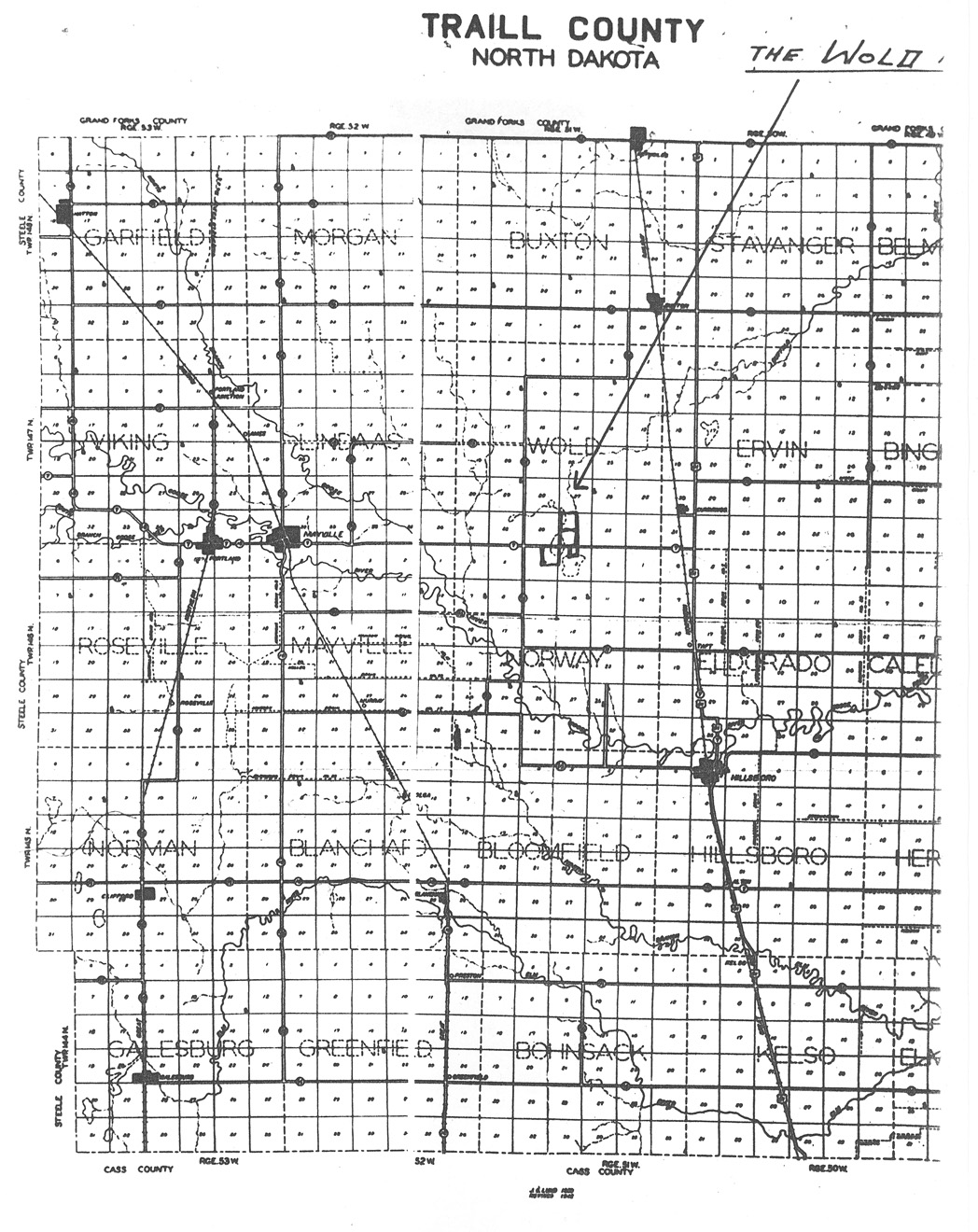

In 1878, Nels H. Wold, an immigrant from Norway, filed a claim under the Timber Culture Act. He paid a $14 filing fee to the federal government when he filed the claim. (See Document 4) Under the law, he was required to plant 2,700 trees per acre on 10 acres. If, after 13 years, 675 trees per acre were still alive, Mr. Wold would receive “patent,” or title, to that quarter section. He planted the trees in the northwest quarter of section 34, in Township 147N of Range 51W. (See Map 1)

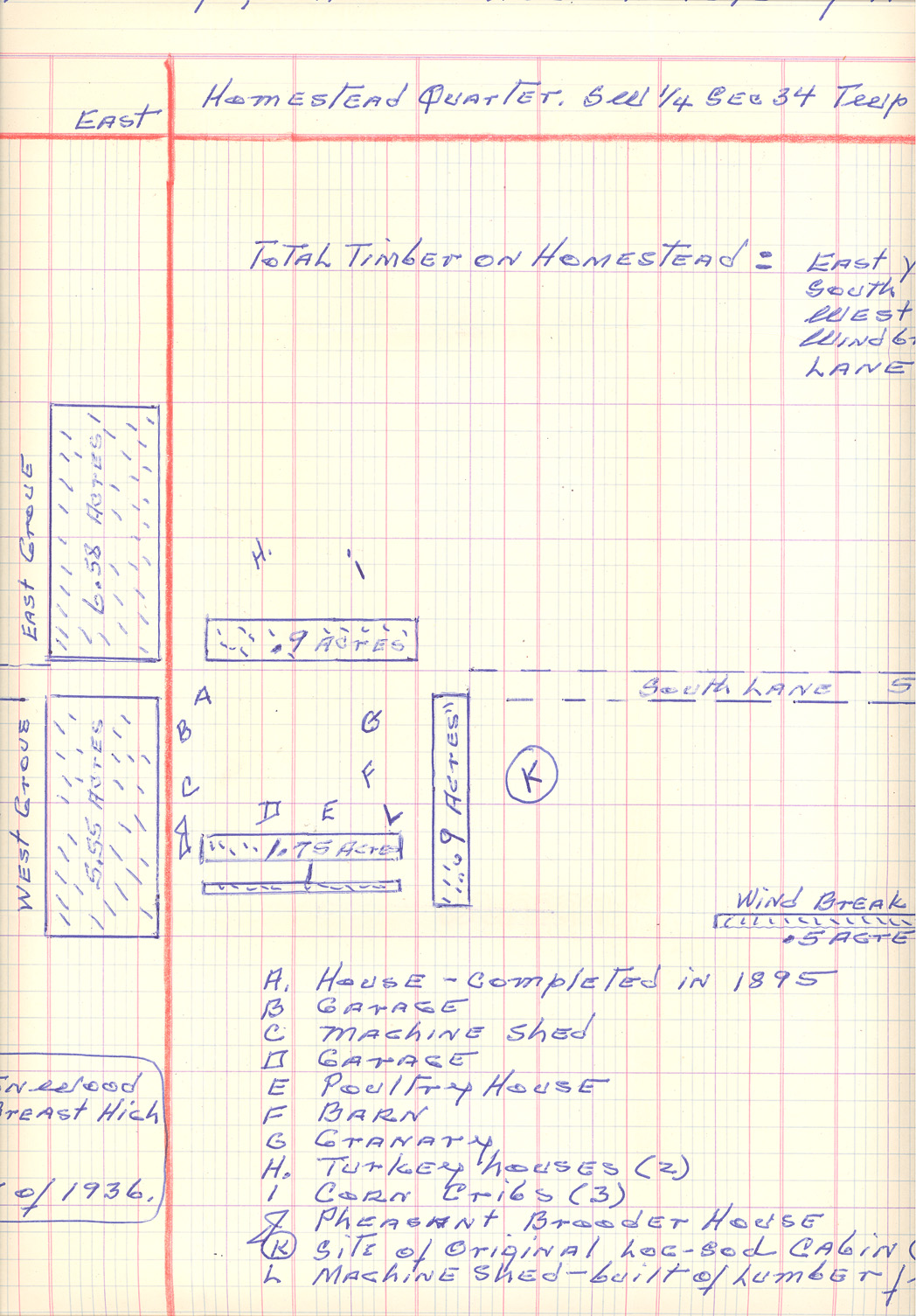

Mr. Wold, who lived along the Goose River in the Red River Valley, actually planted just over 17 acres of trees. He planted according to the plan laid out by the law:

Year 1. Break [plow] 5 acres of ground

Year 2. Break 5 more acres of ground; plant grain on acres broken in Year 1.

Year 3. Plant trees on ground broken in Year 1; plant grain on acres broken in Year 2.

Year 4. Plant trees on ground broken in Year 2. (See Document 5)

Mr. Wold kept on breaking ground and planting grain followed by trees until he had more than 10 acres of trees. He stated, in the “Testimony of the Claimant” that he “did not plant any [trees] during the 4th year for the reason that I had planted the full 10 acres required during the 3rd year. But cultivated protected and kept growing the 10 acres planted during the 3rd year.”

Question 10 on the Testimony form asked: “Describe the condition of the trees now growing. . . , giving their average diameter and height, . . . the kind or kinds of trees, [and] the number of trees per acre now growing. . . .” In answer to that question, Mr. Wold wrote: (See Map 2)

“Good healthy thrifty growing trees. Average diameter about 3 in. . . . right about 13 feet. (See Image 12) Mostly Box elder timber trees with a few Cottonwood ash & oak trees planted to replace a few that died. There are at least 1610 trees and more to each acre. I know these facts from personally counting the trees and measuring their height and diameter” (January 26, 1891) (See Image 13)

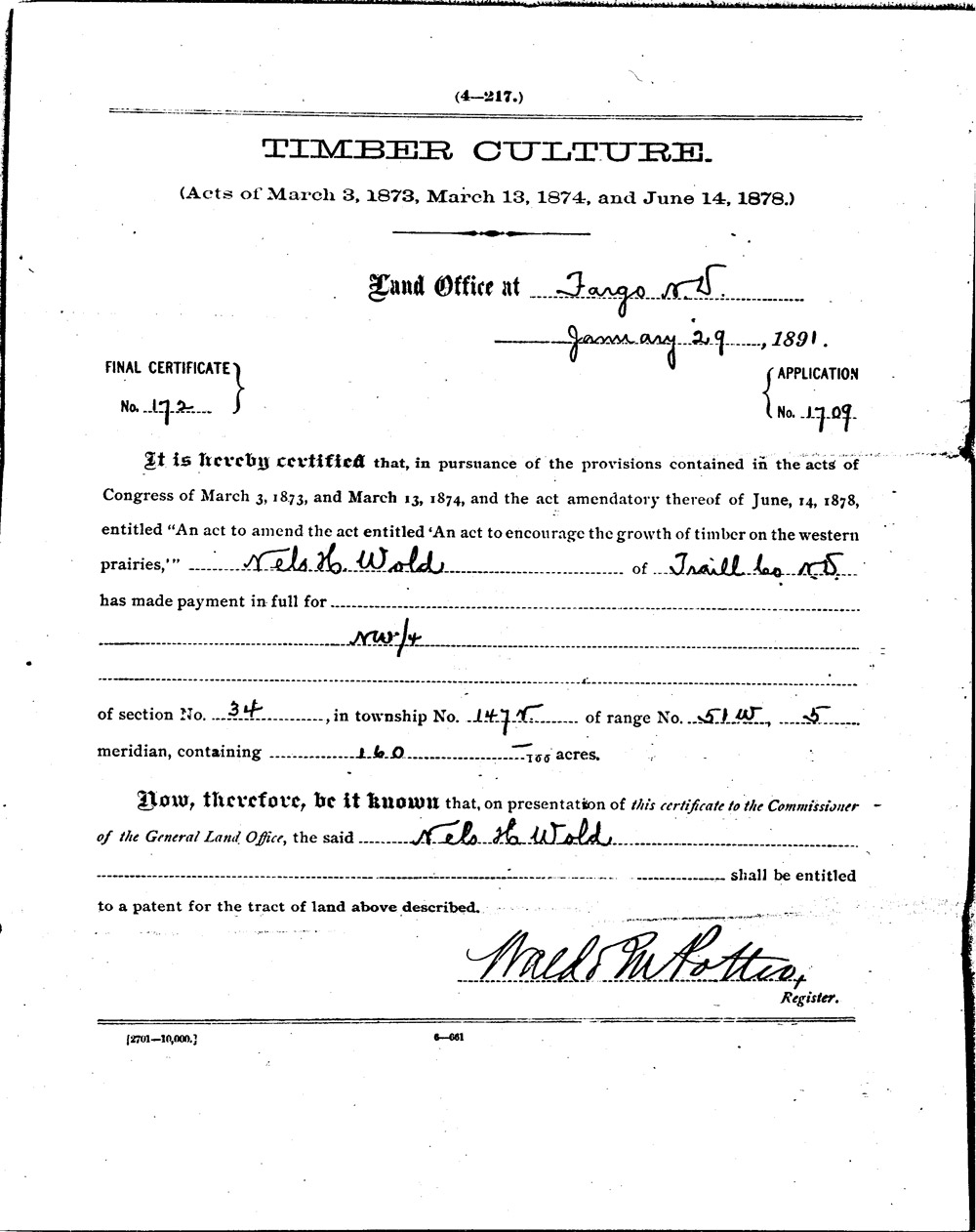

Mr. Wold’s success rate was unusually high. (See Image 14) He had the advantage of living in the Red River Valley which has more rainfall than most of North Dakota. He received his final certificate on January 29, 1891.

Source: A.H. Wold Papers, SHSND MSS 20375