Floods occur regularly along North Dakota’s rivers. Flooding has some long-term value for the soil and plants, but since humans took up permanent homes, farms, and businesses in northern Dakota Territory, floods have been less welcome. They are considered to be a geologic hazard.

The Red River floods often, about one out of every three years. The problem with the Red River is that it runs north into colder temperatures. (See Image 13) As snow melts and runs into the river, and river ice thaws in the southern end (the source of the river), the water cannot flow to its mouth until the river thaws at the northern end. Ice forces the river out of its banks until warmer weather allows the river to carry off the snow melt. Flooding on the Red River generally occurs in late March and April. Occasionally, a heavy summer rain will bring some local flooding to the Red River Valley. Flooding usually occurs along rivers, but in the flat Red River Valley, overland flooding can occur with snow melt or with a very heavy summer rain.

The Missouri River also has a long history of flooding. The Mandans, Hidatsas, and Arikaras who lived along the Missouri and its tributaries usually built their winter homes on the lowlands near the river. Here they had access to timber and shelter from the wind. In the spring, they moved to their permanent earthlodges up on the plateau. Spring floods often damaged their winter homes, but the moisture the river left behind watered the gardens on the floodplain.

Flooding on the Missouri River usually occurs in June because the water flows from the Rocky Mountain snow packs in Montana. (See Image 14) People who live on the Missouri River call this the “June Rise.” It takes a few months of warm weather and a few weeks of river flow time for mountain snow meltwater to reach North Dakota’s cities. The business and residential center of the city of Bismarck was built on the high banks of the river above the flood level. However, people who could not afford to pay for city lots often built houses on the less expensive land on the river’s edge. They sometimes lost their homes to flooding.

The severity of river floods depends on several factors. The water content of the soil, the quantity and moisture level of the winter snow, and the thickness of the ice are just a few of the factors that determine how bad a flood will be.

North Dakota also has long-term floods such as those that occur when Devils Lake rises. While Devils Lake is the state’s largest lake with a long-term flood problem, many smaller lakes have also overflowed onto farmland and highways.

A summer flood destroys crops in fields along the rivers, but the remaining moisture can be useful if the following summer is very dry. The water stored in the soil will support crops even without rain.

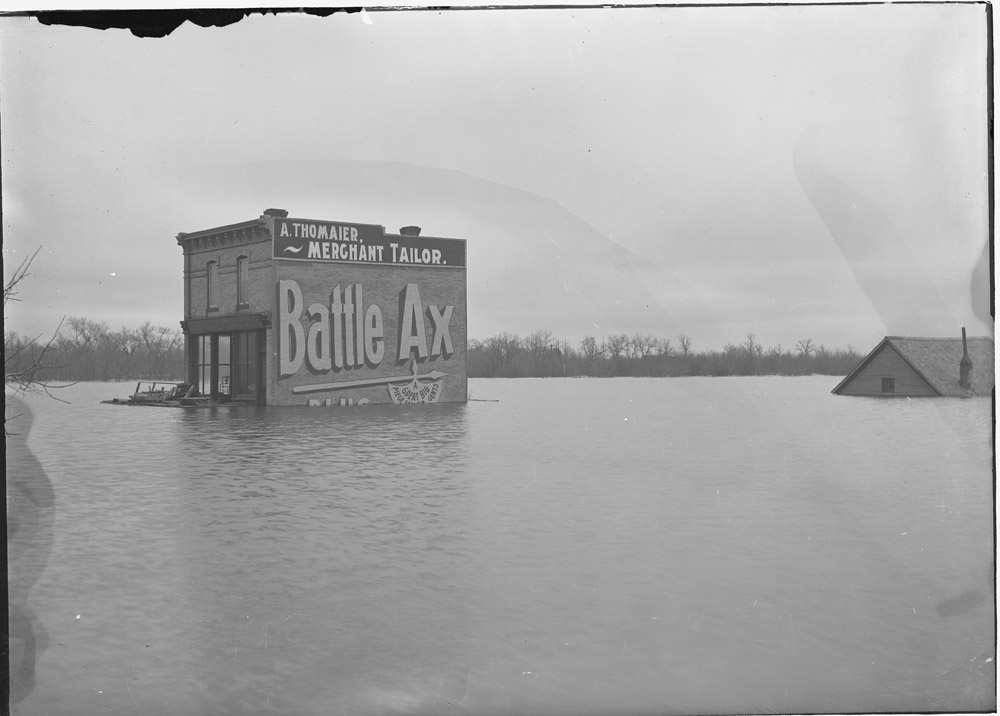

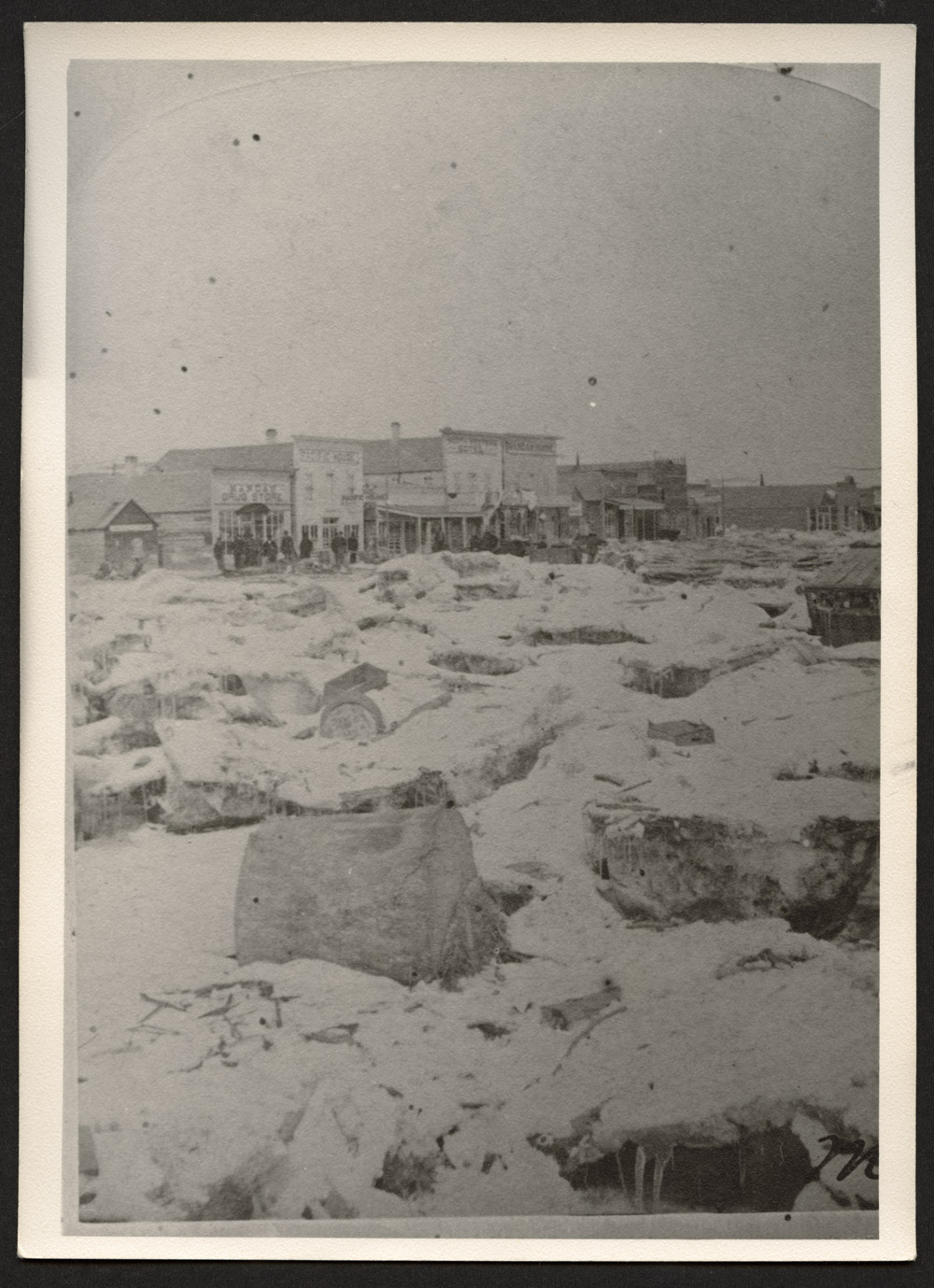

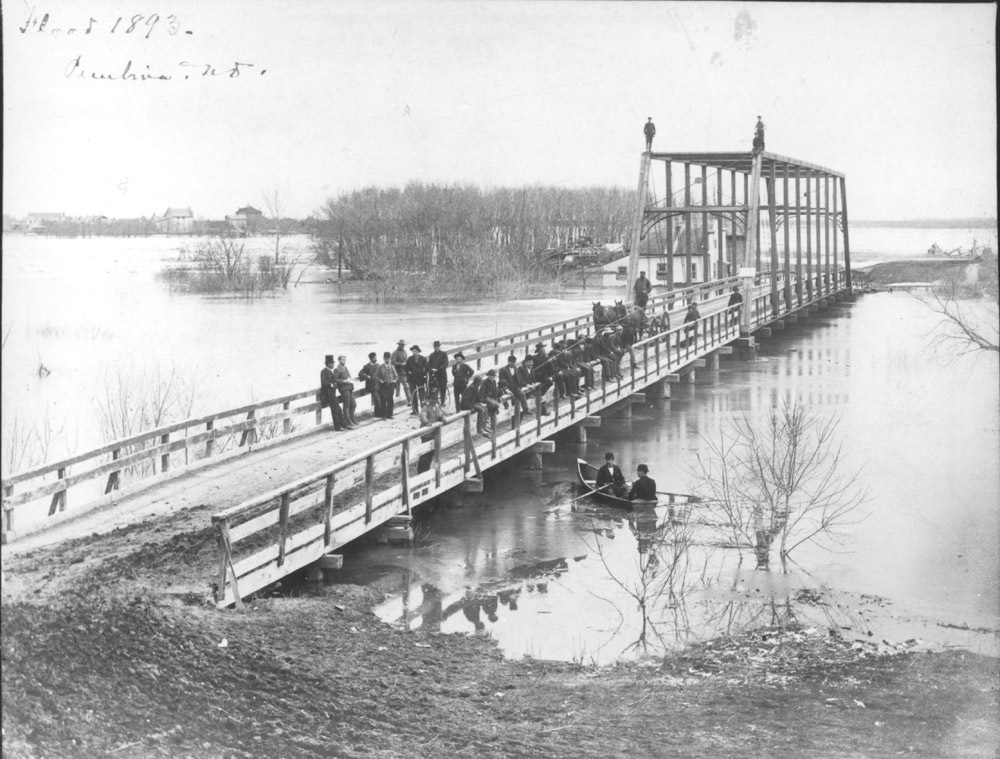

Fargo suffered a major flood in 1897. (See Image 15) Pembina, also on the Red River, flooded in 1890. (See Image 16) Other cities also experienced flooding in the early years of settlement. Soon after flooding, residents began to think of ways to protect their cities against flooding by building dams, canals, and flood walls. North Dakota’s representative to Congress, John M. Baer, asked Congress to fund dams on the Sheyenne and other rivers. Some of those flood protection structures have been built, but they were not completed until several decades after Mr. Baer’s speech on the issue.

Why is this important? Despite regular flooding, cities continued to grow along the rivers. The rivers provided water and transportation for early settlers. Railroads often set up railroad yards near the rivers because their construction was delayed at that point while preparing to build a bridge. Businesses prospered along railroads and rivers, so people built homes, schools, and churches nearby. People who lived along the rivers expected regular floods and prepared to deal with flooding whenever it happened.

Floods, however, were costly. People had to clean up or re-build their homes and businesses. All business stopped during a flood. Farm fields were devastated or too muddy to allow for plowing. City, state, and federal governments had to help the flooded cities return to their normal state. Flood protection systems such as dikes and flood walls were also expensive. Taxpayers often turned to the federal government to find funding for flood protection.

Fargo Flood 1897

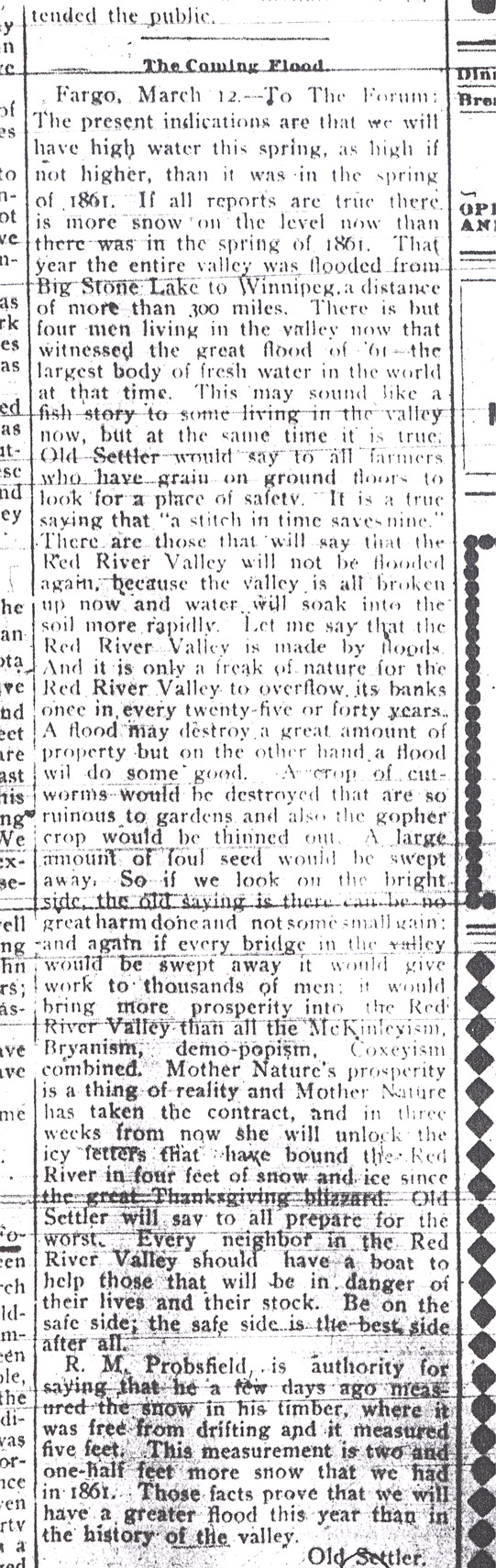

On March 15, 1897, someone who called himself “Old Settler” notified the Fargo Forum and Daily Republican that Fargo was about to experience a severe flood. (See Document 11) Spring floods had been known to fill the Red River Valley with snowmelt runoff. The earliest pioneers remembered the flood of 1861. That spring, the Red River Valley was under so much water that it was called the “largest body of fresh water in the world” – for a few weeks, anyway. (See Document 12)

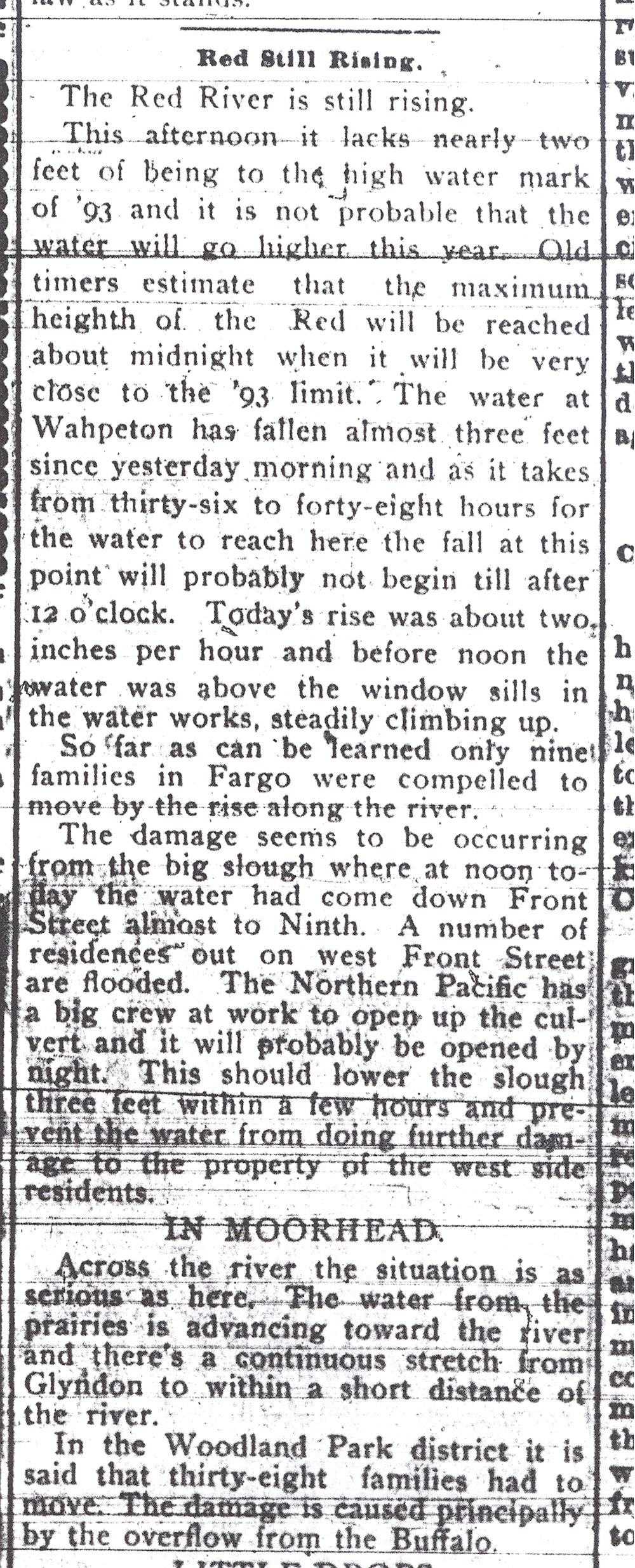

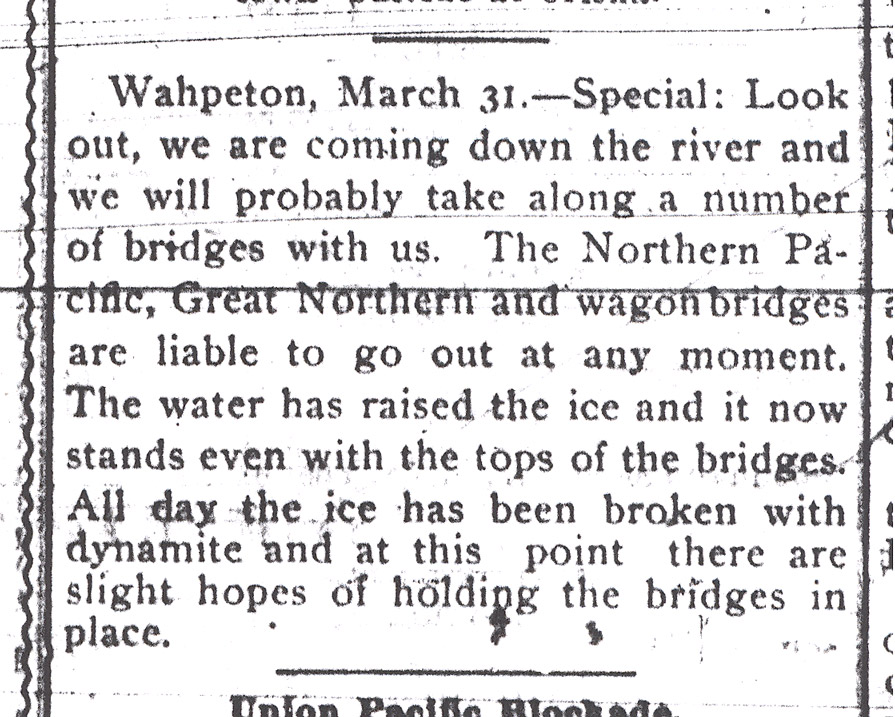

Old Settler was right. By April 1, 1897, the Red River flowed over the railroad tracks between Fargo and Wahpeton. (See Document 13; See Image 17) The Sheyenne and the Wild Rice rivers, tributaries to the Red, were flooding, too. (See Document 14) The high waters of the Red River forced the waters of the tributaries to back up and flood fields and towns along their banks. (See Image 18) Tributaries all along the river backed up. Grand Forks flooded, as did many other towns from Wahpeton to Winnipeg, Manitoba. Flooding occurred in other rivers in the state. (See Document 15)

Fargo had flooded in the spring of 1871, 1873, 1882, and 1893 (and a devastating fire in 1893). However, during the winter of 1896 – 1897, the snow piled up to more than five feet (60 inches) in depth. This was 2.5 feet more snow than accumulated in 1861. The snow was full of moisture.

Fargo did not have a flood gauge until 1901. However, geologists have calculated that Fargo’s flood waters reached 40.1 feet in 1897. (See Image 19) This was the highest level of flood waters until 2009 when the Red River crested (reached its peak and began to fall) of 40.84 feet. Pop-up The 1897 flood is considered the benchmark, or the standard, by which other floods are measured on the Red River. (See Image 20)

There are several factors that contribute to flooding on the Red River. One is that the valley and the river are very young, geologically speaking. The Red River has not carved a deep channel to contain the spring run-off from snow melt. (See Image 21) In addition, the Red River has a very slight drop. The river falls about 1 foot per mile. This means that water tends to flow slowly. The slow discharge of flood waters means that flood damage is generally greater. The twists and turns in the Red River’s path create more obstacles to flood water passage.

Another factor in Red River flooding is climate. The Red River flows from the south to the north where it empties into Hudson Bay. Since the spring temperatures warm up earlier in the south, the river ice melts in the south before the river thaws in the north. This means that the river begins to flow north before the ice in the north has melted, contributing to flooding. (See Image 22)

The flood of 1897 was not the last. In 1920, North Dakota’s representative to Congress, John M. Baer, asked Congress to consider an engineered solution (dams, dikes, etc.) to the devastation of regular flooding in the Red River Valley. In the five years before Mr. Baer’s speech, flooding occurred in 1915, twice in 1916, and in 1917. (See Image 23) Congress offered a little help with drainage channels, but small dams were not built for several more decades. Because the Red River doesn’t have a deep valley, it is very difficult to build a flood control dam on the river.

Red River Flood Control

In 1920, John M. Baer, one of North Dakota’s representatives to Congress, spoke to the House of Representatives about flooding in the Red River Valley. Baer introduced Herbert A. Hard, who was North Dakota’s drainage and flood-control engineer. The two men spoke of the need for federal funding for flood control projects on the Red River. (See Document 16)

Mr. Hard and Mr. Baer tried to impress upon Congress the huge impact that floods had on cities and on agricultural production. Mr. Baer recommended that the Army Corps of Engineers take the lead since flooding was an interstate problem involving North Dakota, Minnesota, and South Dakota.

The two men stated that the Red River Valley included 85,000 square miles, or 22,000,000 acres in its WatershedA watershed includes all the streams and tributaries that feed a major river. The watershed of the Red River in North Dakota includes the area drained by the Sheyenne, Wild Rice, Goose, Elm, Turtle, Park, and Pembina rivers. There are other rivers draining into the Red from Minnesota and Manitoba, Canada. All of these rivers are part of the watershed of Hudson’s Bay. The James and the Missouri rivers are tributaries of the Mississippi River. The watershed of the Missouri River starts in the Rocky Mountains in western Montana. (not including the portion of the valley that is in Canada.) Of the 22,000,000 acres in the Red River Valley, approximately 4,000,000 acres would be improved by a flood control project.

Mr. Hard described the Red River Valley’s unique characteristics. “This is a very level country of which we are speaking; an old lake floor with the characteristically level surface of such a geological structure. . . . [The river] is very sluggish and has a drop of less than 1 foot to the mile.”

Mr. Hard’s proposal was for “channel improvement and ditches [to drain away the water falling on the flat valley,] but we must arrest the rainfall in the higher counties to prevent its rushing down to gorge the channels of rivers in the lowlands. This, I take it, must be done by great impounding dams and reservoirs. . . . These will hold the water for from a few days to a few weeks – until the lowland streams have had time to drain adjacent farms . . . . We recommend that reservoirs be placed at [Minnesota rivers], at Lake Tewaukon, and in the gorges of certain North Dakota rivers, as on the Sheyenne, 19 miles north of Valley City.”

The geology of the Red River of the North contributed to the problem of flooding. “Gentlemen,” said Mr. Hard, “you will remember that this is a very recently formed river. I mean from a geological standpoint, during past times. The channel has not yet been cut deep enough, and it is absolutely unable to handle the floods which we get from two to three times in a 10-year period in this region, with an increasing frequency and intensity.”

“Much of [the money spent previously on flood control] has been a waste. Much has been spent on local, ill-conceived ditches which have helped a few people, but have often aggravated the general conditions. Many ditches were too small, some even do not go in the right direction,” said Mr. Hard.

“This region was flooded after it had been farmed for a number of years. . . . There were prosperous farms in this locality; the farmers had tree claims of well grown trees, 25 to 50 feet high, over the valley. . . . Cat-tails had grown up all over this section, including parts of the three adjacent States. The land from just east of Hankinson eastward to Tintah, Minn., about 28 miles, was one continuous sheet of water. . . [After three years these] lands have since been plowed up and are going back into cultivation again.”

Mr. Hard noted the financial impact of flooding. “We had in 1915 losses, as I had estimated it, in agriculture alone of $15,000,000; in 1916, when we had two floods, one in April and another in July, we had losses of over $20,000,000, and in 1917, the losses were at least $15,000,000.”

Mr. Hard also stated that the “water-logging of soils that can not be drained in time in spring to permit the seed to be put in the ground on time,” cost the state in crop failures. “This late seeded grain is always stricken with rust. . . .” Estimates placed the cost of “rust loss in North Dakota at $275,000,000 the last four years, a staggering figure.”

In conclusion, Mr. Baer stated: “The Red River Valley of the North is the richest and deepest in soil deposit of any valley in the world, being comparable only to the fertility of the Nile. Like the Nile, the flood problem is of prime importance. Its available land forms a great natural garden 600 miles long and from 25 to 60 miles wide, producing an enormous quantity of grain each year. It has well been called the “breadbasket of the world.” The wheat from the Northwest makes the highest grades of flour. The world needs this wheat, as it is absolutely essential to make standard flour. The famous Red River Valley potatoes are known throughout the land, and many other food products are raised in this fertile glacial lake bed. The most progressive, thrifty, and intelligent farmers of the Northwest live here, and the problem of properly protecting them and their homes from ever recurrent floods and saving millions of dollars in crop losses is one that can not be evaded or neglected.”

Why is this important? The Red River of the North has flooded for centuries, but it became a problem when people began to build permanent homes, business structures, and farms in the river valley. North Dakota has sought a solution to flooding on the Red River since 1889. Today, the Red River of the North still floods regularly. Cities along the river banks have undertaken flood control projects, but until recently there has been no unified, inter-state approach to dealing with flooding in the Red River Valley. Today, the cities of Fargo and Moorhead are working to remove houses and other structures that can be damaged by recurring floods and to route flood waters through channels west of the city of Fargo.