Today, the Mandans, Hidatsas, and Arikaras share a reservation. In the late 19th century, all three tribes lived together in Like-a-Fishhook village. However, the path to forming an alliance and a community was sometimes troubled.

The Hidatsas began as three related, but culturally different, societies. There were the people who called themselves Hidatsas (sometimes called Hidatsa-proper). There were also the people who went by the name Awatixa (Ah wah TEE hah) which means the People of Rock Village. The other group of people called themselves the Awaxawi (Ah wah HAH wee) meaning People of Mountain VillageThe name people have for themselves was often corrupted by outsiders. The Mandans called the Hidatsas “Minitari” which means “cross the water.” When Europeans came to the villages they used the Mandan word calling the Hidatsas Minitari, or Minitaree. French traders used a different name. They called Hidatsas the Big Bellies, or Gros Ventre (gro VONTR) in French. Gros Ventre became the name that the United States government and the Army used when talking to or about the Hidatsas. These three groups thought of themselves as different from one another. For many years they lived near one another and were friendly, but they did not form a tribe.

When the Hidatsas moved to the Missouri River, they met the Mandans who lived near the mouth of the Heart River. The Mandans, like the Hidatsas, spoke a Siouan language and lived in earthlodges and raised garden crops. But the Mandans were cautious about having another village nearby. They suggested that the three groups of Hidatsas should move a short way up the Missouri River.

In 1781, the Hidatsas, Awatixas, and Awaxawis suffered greatly from the smallpox epidemic. Their populations fell dangerously low so they could not defend themselves effectively against outsiders. A sacred leader promised them that if they moved north to the Knife River, they would prosper and become as “numerous as the willows.” To better protect themselves, the three groups joined together, but lived in several villages. Following the words of the sacred leader, they called themselves Hidatsa, People of the Willows.

The Mandans also suffered terribly from the smallpox epidemic of 1781. They also moved to the area near the Knife River and built a new village. The Mandans and the Hidatsas continued their friendship.

The Arikara, who called themselves Sahnish,Today, the Arikaras prefer to be called Sahnish. However, in the historical record, you will see the words Arikaras, Ricarees, and Rees. In these texts, we use both Arikara and Sahnish. Both words refer to the same people. were also earthlodge dwellers who lived near the Missouri River. They spoke a dialect of the Caddoan languages. (See Document 1.) They were related to the Pawnees who lived farther south on the Missouri, but the Sahnish, following sacred instructions of Chief Above, began a slow journey northward on the Missouri River. The historic record shows that the Sahnish had moved as far north as the Cheyenne River (central South Dakota) by 1780.

Document 1. Languages of the Three Tribes

Hidatsa and Mandan are Siouan languages. This means that at some time in the very distant past, the Mandans and the Hidatsas might have been part of a group of people who spoke the same language. Long ago, those people broke away and formed a separate society. The languages changed over time, but retained similarities which reveal their early, common root language.

Linguists (people who study language) have identified approximately seven language groups in North America before the arrival of Europeans. Siouan is one of these language groups; another is Caddoan. The Arikaras spoke a Caddoan language.

By looking at a few simple words, you can see similarities and differences in the languages spoken by the Three Affiliated Tribes. You can also see that the Mandan word for earthlodge was adopted by non-Indian settlers to name the town of Makoti.

The languages of all three tribes are considered endangered today.

|

English Word |

Hidatsa Word |

Mandan Word |

Sahnish Word |

|

Buffalo bull

|

kedapi |

wrór |

tanáha' |

|

Earth (dirt, hill, etc)

|

ama |

Ma ak |

(unknown) |

|

House

|

ati |

Ti |

akaánu' |

|

Earthlodge

|

awa ati |

ma’ ak oti |

akanaanataá'u' |

After the smallpox epidemic of 1781, the Arikaras approached the Mandans asking if they, too, could live nearby. The two tribes agreed that the Arikaras would build a village nearby. In a few years, however, the Arikaras quarreled with the Hidatsas and Mandans. The Arikaras moved back to the Grand River before 1804. In the spring of 1805, the Arikaras approached the Mandans about building nearby once again. That arrangement did not work out.

Between 1820 and 1833, the Sahnish lived on the Grand River. For a few years, they rejoined the Pawnees in Nebraska, but in 1836, they returned to the Upper Missouri. They forged a new alliance with the Mandans and Hidatsas. Unfortunately, this move occurred just as the smallpox epidemic of 1837 broke out. Once again, the Arikaras, along with their new allies, suffered a very high death rate from smallpox.

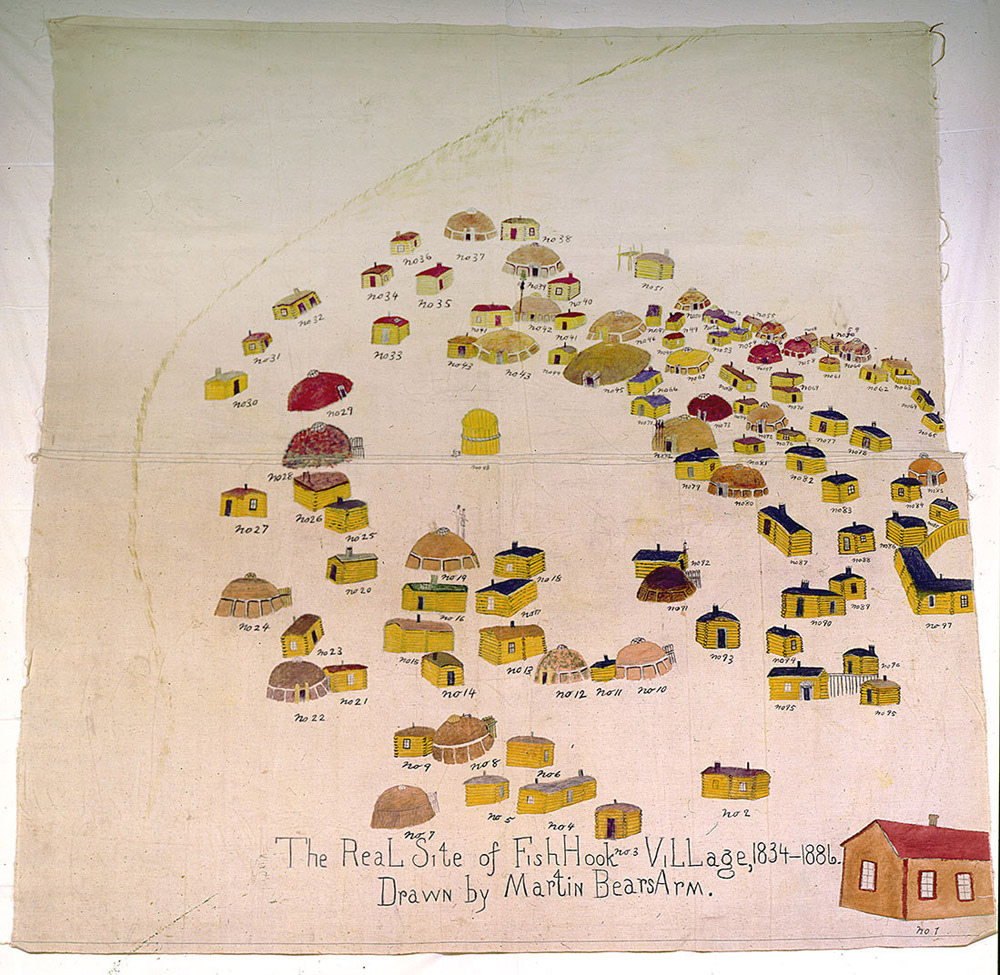

In 1845, the Mandans and Hidatsas built a new village north of their Knife River site. (See Image 1.) This village, called Like-a-Fishhook, was the new home for the Mandans and Hidatsas and became a trade center when Fort Berthold was built nearby.

Document 2. Waheenee Moves to Like-a-Fishhook Village

Waheenee was the childhood name of Maxidiwiac, or Buffalo Bird Woman, a Hidatsa woman. She told anthropologist Gilbert Wilson her memories of the move from the Five Villages on the Knife River to the new village at Like-a-Fishhook Point. Waheenee was four years old when the people moved to the new village in 1845.

Our chiefs, Mandan and Hidatsa, held a council and decided to remove farther up the Missouri. “We will build a new village,” they agree, “and dwell together as one tribe.”

The site chosen for the new village was a place called Like-a-Fishhook Point, a bit of high bench land that jutted into a bend of the Missouri. We set out for our new home in the spring, when I was four years old. I remember nothing of our march thither. My mothers have told me that not many horses were then owned by the Hidatsas, and that robes, pots, axes, bas of corn and other stuff we packed on the backs of women or on travois dragged by dogs.

The march was led by the older chiefs and medicine men. My grandfather was one of them. His name was Missouri River. On the pommel of his saddle hung his medicines, or sacred objects, two human skulls wrapped in a skin. They were believed to be the skulls of thunder birds, who before they died, had changed themselves into Indians. After the chiefs, in a long line, came warriors, women, and children. Young men who owned ponies were sent ahead to hunt meat for the evening camp. Others rode up and down the line to speed the stragglers and to see that no child strayed off to fall into the hands of our enemies, the Sioux.

The earth lodges that the Mandans and Hidatsas built, were dome-shaped houses of posts and beams, roofed over with willows-and-grass, and earth; but every family owned a tepee, or skin tent, for use when hunting or traveling. Our two tribes camped in these tents the first summer at Like-a-fishhook Point, while they cleared ground for cornfields.

Source: Waheenee: An Indian Girl’s Story (St. Paul, Minnesota: Webb Publishing Company, 1921): 11-12. https://archive.org/stream/waheeneeanindia00wilsgoog#page/n6/mode/2up

The three tribes have lived close to one another since that time. When the Fort Berthold Reservation was established in 1870, it was home to the three tribes.

Why is this important? Over many centuries, the tribes of the Great Plains frequently formed and broke alliances. When an alliance no longer suited the people, one tribe would move away to another place. For the Mandans and Hidatsas, similar languages and cultures helped them maintain a long-term alliance. The Sahnish, whose culture was similar in some ways, but very different in other ways, were uneasy in their alliances.

Trade, war, and disease forced each of these tribes to consider how an alliance might help or endanger their people and resources. Of these three factors, disease was by far the most powerful. Once their populations had been decimated by disease, the alliance gave the tribes the strength to defend themselves against attack. Alliance, however, did not mean that the three tribes lost their cultural distinctions. Throughout their long history together, each tribe retained its distinct language and cultural ways.