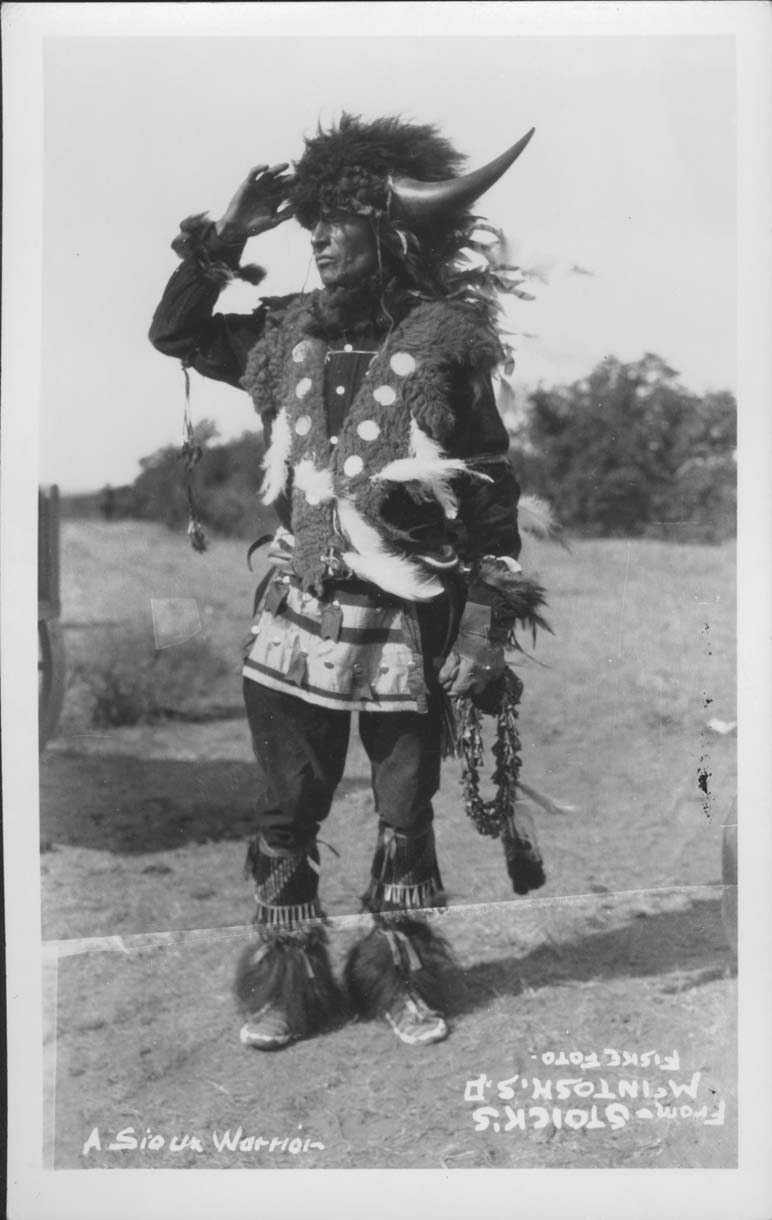

The Lakotas lived in the woodlands east of the Great Plains where they lived as both hunters and farmers until around 1707. The winter count of Battiste Good tells us that by 1707, the Lakotas had both horses and guns. They acquired guns and horses through trade networks which linked Indians to European Americans. (See Image 3.)

By the middle of the 18th century, the Lakotas were primarily bison hunters. They hunted for food and hides. The surplus in hides was traded to other tribes or to Anglo-Americans for other things they needed. Women prepared the hides for trade by stretching and tanning the hides. They also decorated the hides in order to get the best advantage in trade. In the late summer or early fall, Lakotas traveled to the Mandan villages to trade bison hides for corn which they needed for a good diet.

As the time for the communal hunt approached, the Lakotas began making plans. The hunt could not take place until a spiritual leader had a vision. The vision might tell the people that the time to hunt was right, or it might tell them to wait a while. Either way, the people listened carefully to the advice and followed it.

After the proper spiritual ceremonies had been completed, the council met to discuss the hunt. The council members smoked a pipe in the appropriate ceremonial manner and carefully discussed the hunt. They decided when and where the hunt would take place. The discussion might have lasted a few hours or several days. The council ended with a great feast prepared by the women of the village.

Before the hunt began, the council chose four young men to organize and maintain order in the hunt. These men were called akicitas (ah kee CHEE tahs) or marshals. Each of the marshals wore a special shirt and carried a feathered banner to signify his role. The akicitas controlled the camp and had the authority to punish anyone who disobeyed.

Before the hunt, women prepared to move the camp. They made repairs to the tipis, harnesses, and clothing. The men prepared their bows and arrows and bison hunting horses for the hunt. They also played a game called hehaka (heh HAH kah) which was a game of speed and accuracy that involved catching a hoop with a stick.

The entire village traveled between 10 and 25 miles each day. Even very small children, elderly people, and those who were sick went with the village on the hunt. They stopped where there was enough water and wood for a good camp. The people traveled close together and kept watch for enemies. The season for the Lakotas’ hunt was the time when all tribes were out to hunt bison.

When the camp arrived at a place near the herd, the people, even children and dogs, had to be very quiet so the bison herd would not be frightened. When the scouts discovered a herd, they returned to signal the hunters. Different signals meant different size herds. If the scout waved his robe, then spread it on the ground, it meant that he had seen a herd Battiste Good Winter CountBattiste Good was the last keeper of a winter count that extends 1100 years into the past. On this winter count, there were pictures of a different style of hunting that was used before the Lakotas got horses. When the Lakotas found a bison herd, they built their village in a ring around the herd to keep the animals confined. They had to enter the herd on foot and sneak up to the animals they killed.

First, the Lakotas made an offering to the spirit of the bison. (See Image 4.) The camp herald went through camp calling the people to make ready for the hunt. At first light, the marshals led the hunters silently toward the herd and arranged the hunters so each had a fair chance. At the signal, the hunters rode quickly toward the herd, keeping low on their horses. The bison, not seeing humans, did not run until the hunters released their arrows.

The hunters tried to wound or kill as many bison as possible. They shot an arrow into the bison’s side or chest. An animal that was wounded, but not killed might turn and charge the hunter’s horse. The hunter quickly left the first bison he shot, and rode after another. The hunters continued until the horses were exhausted or all the bison they wanted were killed.

The hunters made a special effort to kill a white bison if there was one in the herd. White bison were rare and considered wakan (wah KAHN) or sacred. A white bison robe made an extraordinary gift or offering. One of the bison carcasses, perhaps a white one, was sacrificed for a good hunt. The hide was removed from the carcass, but the remainder of the animal was left in the field as a sacrifice of thanks.

Each hunter identified the animals he had killed. Soon the women arrived with horses and travois for carrying the hides, meat, and other parts back to camp. The hunters took a fresh liver, dipped it in gall (a bitter fluid stored in the gall bladder), and ate it. Lakota hunters believed that this food gave them strength and courage. Roasted meat was served to the rest of the village. (See Image 5.)

Women now dried the meat, stored the fat, and made wasna (WAHZ nah).Wasna is the word for a mix of powdered meat, fat, and berries. The Chippewas, Métis, and many other tribes called this food “pemmican.” They staked out the hides. (See Image 6.) The men rested.

After all the meat was dried and preserved, the tribe decided if they had enough for the winter or if they needed to conduct another hunt. If they did not need to hunt anymore, the marshals gave up their control of the camp, and life returned to normal.

Why is this important? Bison provided everything necessary for a good life on the Great Plains. The Lakotas chose to live as nomads, hunting and trading, which provided them with a good living and a strong spiritual foundation. However, this life also required that they be constantly prepared for war.