Bison supplied immense quantities of meat for the tribes that hunted on the Great Plains. Some of these tribes, including the Lakotas, Dakotas, Yanktonais, Chippewas, Mandans, Hidatsas, and Arikaras, lived on the Great Plains. Other tribes lived to the east in the woodlands of Minnesota or west in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains and traveled into the Plains every summer to hunt bison. So important was this animal to the well-being of American Indian tribes that they organized themselves every summer to travel as far as necessary to find bison, kill sufficient numbers for winter food supply, and carry the meat back home again. These hunts required careful and exact organization. The tribe’s well-being depended entirely on a successful hunt.

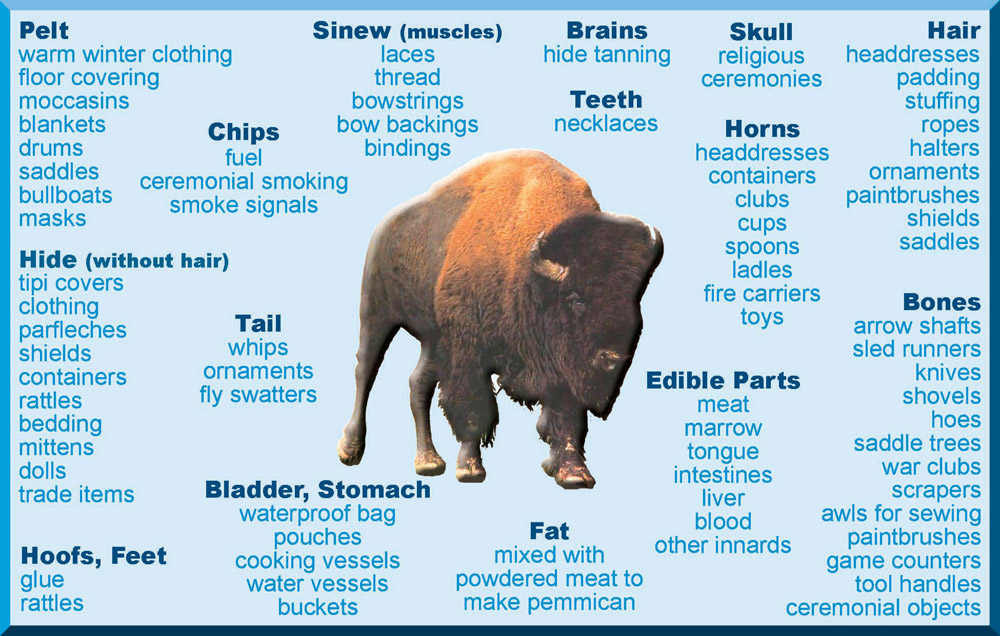

Both nomadic tribes such as the Lakotas and the sedentary tribes such as the Mandans hunted bison. All tribal peoples also hunted deer, antelope, and elk. They also they fished and trapped birds, but no other animal provided the food security that bison did. In addition, all of the tribes utilized bison hides, hooves, heads, horns, tails, bones, and many internal organs to make many of necessities that made for a comfortable life. (See Image 1.) Parts of the bison were even used to make toys for children. (See Image 2.)

During most of the year, any family or village that needed meat could go out to hunt bison, deer, elk, or antelope. However, the big summer and early fall hunts were conducted for the entire tribe. The summer hunt was organized by tribal leaders whose decision had to be obeyed by all members of the tribe. Anyone who approached the bison herd without permission would be severely punished. Usually, one of the young men’s societies was given the authority to maintain order among the tribe so that no one scared off the bison herd.

Hunts were often preceded by religious ceremonies such as the Sun Dance. During these ceremonies, the people made spiritual sacrifices to ensure a successful hunt. For many of the tribes of the northern Great Plains, bison held a special spiritual significance.

The summer hunt was a good time for children to learn many of the important tasks of an adult. Girls learned to prepare food, mend clothing, and pack for hunting camp. Boys learned to hunt and to obey the hunt leaders. There were many rules, skills, and ceremonies that were passed down from parent to child during the summer communal bison hunt. (See Document 1.)

Document 1. Wolf Chief’s First Hunt

Wolf Chief was born into a Hidatsa family around 1850. As a young boy, he accompanied his father and other hunters on the summer hunt, though it was not yet time for him to participate in the hunt. This was his first lesson in the work of adult men of his tribe.

More than 60 years later, Wolf Chief told the story of his first hunt to Gilbert Wilson, an anthropologist who recorded many stories of the old ways of the Hidatsa. The story has been edited slightly. This document is presented with the permission of the Minnesota Historical Society and the American Museum of Natural History. From Gilbert Wilson’s Reports, 1913, part 1, pages 125-141.

My First Buffalo Hunt

When I was about twelve years of age, all the people of our village went on the west side of the [Missouri] River toward what is now the town of Dickinson, for we had heard that buffalo herds were there. We crossed the river in bull boats. . . . My father, Son of a Star, was chosen leader of the hunt, and Belly-up was his crier. We made our first camp just outside of the timber of the Missouri.

The next morning our people struck tents. . . . The young men [went] along the side of the road on horseback. In old times when we made a march like this, a large number of the people walked. . . .

The season of our march was in the first part of July. Before we had left Like-a-fish-hook village, all the families had hoed their gardens free of weeds so that we could leave them in safety, knowing that our crops would be in good condition when we returned.

We made six or seven camps before we found any buffaloes. As we came near to Cannonball River, my father sent two young men ahead to see if they could find any buffaloes. They returned saying, “There is a big bunch of buffaloes over there.” They made their report on their return in the evening. Everybody got ready for the hunt the next morning.

We arose early in the morning, and my father saddled two horses while I also saddled one, for I was going with the hunting party. I had a white man’s saddle, small for a boy, which I had gotten from the Crow Indians. Both my father’s horses had elk horn saddles. In the rear of his saddle he tied short ropes in a twist, like a figure eight. This was to be used to bind the meat on the saddle when we came home from the hunt.

The party was made up of about forty men, each leading an extra horse, and eight boys of from twelve to fifteen years of age, each riding a single horse only, not leading one. A boy of sixteen or seventeen years of age was thought old enough to be a hunter. The forty men were young men, or men in their prime, that is, of hunting age. With us boys, who did not expect to take part in the actual hunt, there went three old men, one of them carrying a bow and arrows. I do not think that he really expected to use them but carried them more for the sake of old-time customs. The three old men and we smaller boys, were not expected to take part in the actual chase of the buffaloes.

The leader of the hunt had been appointed the night before. He was Belly-up, or E-da´-ka-tas. Our name for a leader of the hunt was Matse´-aku´-ee, or, keeper of the men. The name for my father’s office, leader of the tribe on the march, we called Madi-aku´-ee, or tribe-traveling keeper.

Belly-up went on ahead and all the rest of us followed. We went out about five miles. Then we sent out two men on ahead . . . to spy out the herds.

We went on at a smart trot. Pretty soon we saw our two spies returning. They reported to Belly-up that they had located the herds. They returned to us at a gallop, so that we knew before they had reported, that they had news to tell. Belly-up now pressed forward faster, and we all followed at a gallop. All the men had quirts, as had Belly-up himself, and I remember how the quirts would come down, “Slap, slap,” on the horses’ flanks, and the hoofs go “Beat, beat,” on the stones.

About a half mile from the buffaloes we stopped on the hither side of a hill which hid the buffaloes from our view; and the men took the saddles off of the horses which they were riding, and put bridles in their mouths made of raw hide ropes, and remounted.

Belly-up went off a little way, took out a piece of red calico that he had, tore a strip off of it and tore the strip into three or four pieces. These pieces he put on the ground as he faced in the direction of the buffaloes. He spoke something, evidently a prayer. I could not tell what he said, but I knew that the red cloth was a sacrifice to the buffaloes.

Everybody now got ready and the men mounted their horses, and stood in a long line facing the buffaloes, with Belly-up on the extreme right. Of course, I mean only the hunters. The line now started forward at a sharp gallop, with all the heads and necks of the horses even, in a long line. A soldier Indian, a man named Tsa-was, rode in front, and if any man got too far forward in the line, Tsa-was, or “Bears Chief,” would strike the horse in the face.

We boys had to follow behind with the three old men. These were old men of about sixty, or more. One of them, as I have said, had his bow and arrows along, but all the young men in the hunters’ line had rifles. We were all on the leeward side of the buffaloes.

As we came over the brow of the hill we sighted the buffaloes, about four hundred yards away. Belly-up gave the signal, “Ku kats! --- Now’s the time!” Down came all the quirts on the flanks of the horses, making the little ponies leap forward like big cats. . . . Everyone now wanted to be first to get to the herd and kill the fattest buffalo.

I was somewhat scared, for the horses were at break-neck speed and my pony took the bit in his mouth, and went over the rough, stony ground at a speed that I feared would break his neck and mine too.

“Bang!” went a rifle. A fat cow tumbled over. “Bang! Bang! Bang! Bang!” The herd swerved around, and started up wind as buffaloes almost invariably did when they were alarmed. . . .

The herd went tearing off. Only a fast horse could overtake buffaloes, and indeed, a fleeing buffalo could outrun many speedy horses. We killed only cows. The flesh of the bulls was tough, and that of calves, when it was dried, became soft and was easily broken into pieces. For this reason, we did not often kill calves, although we sometimes did for the skins. . . .

My father had killed three fat cows in the hunt, for he was along with the party. He butchered the cows and brought his [spare] horse (which he had left behind the hill, hobbled,) and loaded it with meat. He put a little of the meat also on the horse that he rode, but none on the pony that I rode.

As he was cutting up the carcass, I saw him throw away what I thought was a good piece of meat. I hated to see that piece of meat wasted, and when I thought he was not looking, I picked it up and threw it back on the pile. When we got home, I overheard my father say to my mother, “Our boy is not a wasteful boy --- he want to save what he has. He threw back on the pile of meat, some tough leg meat that I had thrown away. He did not want to see it wasted.”

He returned back to the camp from the place of the hunt much more slowly than we had gone thither. Sometimes we went at a trot, very often at a walk. . . .

. . . Almost every part of the buffalo was used in the old times. The choice cuts , with the shoulders and hams, we carried home, but the spines, neck, and heavier pieces we left behind on the prairie, covered over with hides. . . .

The next day we came back to the place of the hunt for the meat which we had left behind. We found it safe, and carted it back to camp. . . .

We spent two days drying the meat and making bone-grease. We did not dry the meat in smoke but on stages in the open air.

The tribes used different techniques in hunting. Some drove bison herds over a cliff or into a small canyon. Others surrounded the herd and then approached for the killing. As soon as the bison were killed, women removed the hides and began to cut the meat into pieces. Usually some of the meat was consumed immediately as the tribe or band celebrated a successful hunt, but hundreds of thousands of pounds of meat were dried for winter use. Women sliced the meat into thin strips and hung it on poles in the sun near a small fire to dry. Dried meat did not spoil.

Many of the tribes dried the meat at the hunting camp before returning to their villages. While the meat was drying, the hides were stretched out on the ground and staked down. Women then scraped the hides clean of all flesh and began the process of preserving the hide. Hides might be tanned to be used as robes. Other hides might be left untanned and used as rawhide.

Hunters broke open the bones to remove the marrow which was eaten fresh or used in soups. Marrow is high in calories and protein, so it was a highly valued food. The bones were saved to be made into sharp, strong tools.

Following the summer hunt, the people returned home with many tons of dried bison meat. If they were able to protect their supply of meat from raiders or military attack, they would eat well until the following spring.