Though the Mandans, Hidatsas, and Arikaras grew enormous quantities of corn, beans, squash, and sunflowers, their agricultural practices were very different from the ones farmers use today. In 1915, a Hidatsa woman named Maxidiwiac (Mah HEE dee WEE ah), or Buffalo Bird Woman, described to the anthropologist Gilbert Wilson her methods of growing corn.The Hidatsa word for corn is ko’ xa ti (KO hah tee). She used traditional methods that she had learned from her mother and generations of women before her.

Maxidiwiac was known as Waheenee (Buffalo Bird Woman) when she was a young girl. At the age of 12, she began to assist her mothers (Hidatsa children call their birth mother and her sisters “Mother”) in the garden. Her first job was to sit on the watchers’ stage, a platform where little girls spent the day chasing crows and little boys away from the corn.

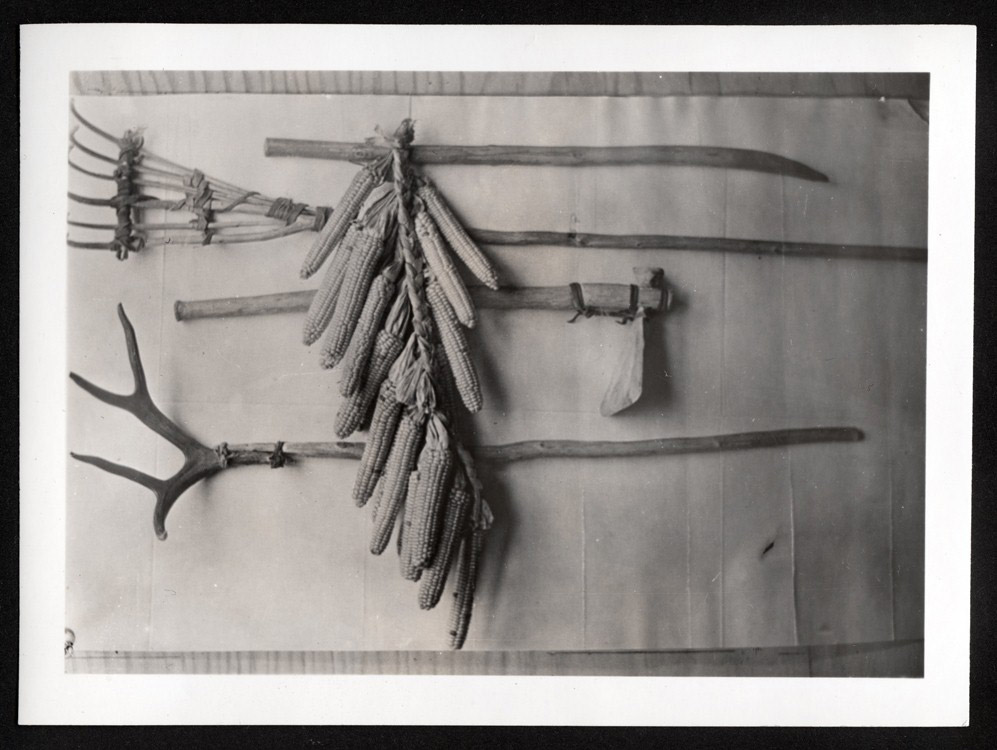

When she grew to be a mature woman, Maxidiwiac had her own garden. She was responsible for planting, protecting, hoeing, and harvesting. Her tools were made of iron and wood, but some women still used the traditional tools made of wood handles attached to antlers for rakes or wood handles attached to bison scapulas for hoes. (See Image 3.) The ground was prepared for seeding by digging with a sharply pointed stick.

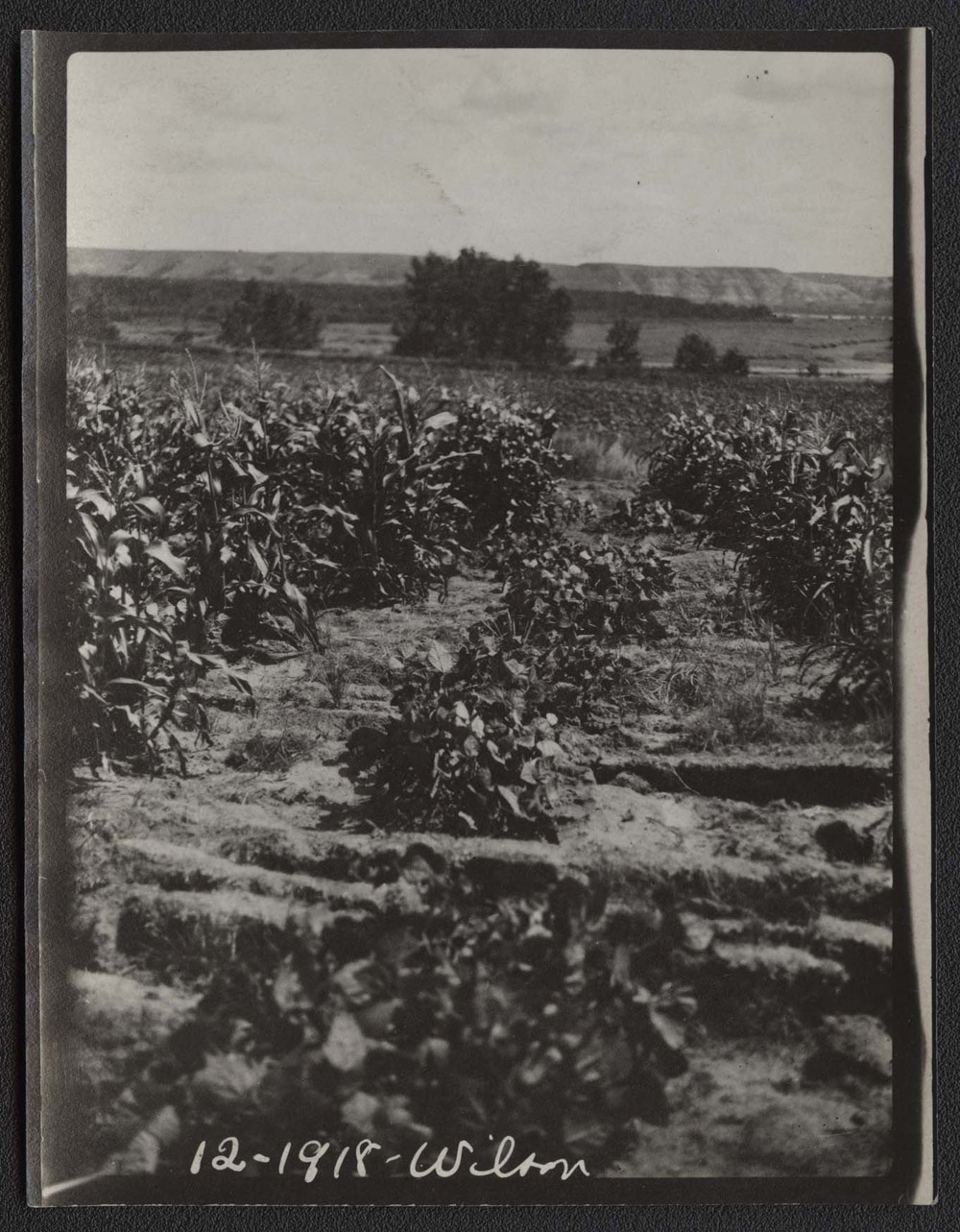

The women gardened on river bottom land. Upland ground (where summer homes were built) was too hard and dry, but the river bottoms were soft and moist. When the leaves emerged on the gooseberry plants, the women started to plant corn. This was in May; planting was not completed until June.

The gardens included sunflowers, beans, squash, and tobacco in addition to corn. The seeds were planted so that each plant could take advantage of the qualities of the other. Beans were planted near corn. (See Image 4.) Several varieties of squash were planted in the wide spaces between sections where different varieties of corn were planted. The broad leaves of squash shaded out the weeds.

First, Maxidiwiac stirred up the dirt of last year’s corn hill with her hoe. She smoothed the soil with her fingers and placed six to eight dried corn kernels from the previous year’s crop in each hole. She patted dirt over the seeds with her fingers and moved on to the next hill which was about four feet away. Each morning, Maxidiwiac planted several rows, each 90 feet long. Other women may have planted more or less corn according to the size of their families. If a woman was ill and could not plant, members of her social groupEvery woman belonged to a society that was appropriate for her age. When she joined the society, she made a gift to the group for her membership and to another woman for her help to join. Women began to join age societies when they were in their teens. would plant for her. If they worked together, they could complete the planting in one morning.

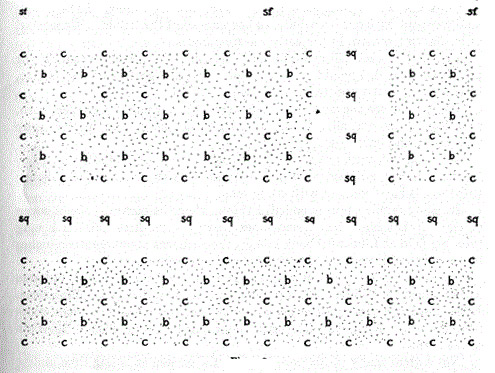

Maxidiwiac’s gardenMaxidiwiac grew nine varieties of corn, the Arikaras grew 11 varieties, and the Mandans grew 14 varieties. Some of these were the same, or very similar to one another. Maxidiwiac’s corn varieties were called ata’ki tso’ki (hard white), ata’ki (soft white), tsï'di tso'ki (hard yellow), tsï'di tapä' (soft yellow), ma'ïkadicakĕ (gummy), do’ ohi (blue), hi’ci c ĕ’pi (dark red), hi'tsiica (light red), and atạ'ki aku' hi'tsi ica (pink top). Each variety had a different use. For instance, ata’ki tso’ki was parched, then pounded with buffalo fat and mixed with cooked squash and beans. (See Image 8) was about three and one-half acres in size. It was divided into sections in order to keep different varieties of corn from cross-pollinating one another. (See Image 5.) As the corn grew, the women hoed daily to keep the weeds from taking over the garden. They made scarecrows from wood frames and old blankets to keep the crows from stealing the young corn.

In early August, Maxidiwiac looked for signs that her corn was ripe. “The blossoms on the top of the stalk were turned brown, the silk on the end of the ear was dry, and the husks on the ear were of a dark green color.” This was “green corn” which was boiled and eaten fresh. Green corn was considered a great treat. Later in the summer, other varieties of corn were harvested and dried on the cob or as kernels. The dried corn was saved for the family’s winter use and for trade. (See Image 6.)

Seed corn was specially selected and set aside. Maxidiwiac “chose only good, full, plump ears” without any sign of disease. She put away enough seed corn to last for two years, so that if the crop failed in the next year, she still had seed for the following year.

Maxidiwiac raised nine varieties of corn. Each type had a different use: some were better for eating fresh, others better for drying. Some corn was ground to make flour. To maintain the purity of their corn genetics, the women kept each variety separate. Maxidiwiac usually coordinated her planting with the woman who had the neighboring garden so that their gardens would not cross-pollinate. (See Image 7.)

Corn was an important food for the Mandans, Hidatsas, and Arikaras, but it also had a spiritual quality. The people of the villages performed certain ceremonies to ensure that they would always have a good crop of corn.

Why is this important? Corn agriculture gave the Mandans, Hidatsas, and Arikaras a secure and reliable source of nutrition. In addition, the tribes were able to trade their surplus corn for other goods and in that way, they became wealthy. Mothers taught their daughters how to raise corn and other crops. Women of the tribes accumulated information on methods of raising corn and maintaining the qualities of specific varieties. It was women’s work, agricultural skills, and knowledge that brought economic and social advantages to the tribes.